An Interview With ‘Playboy’ Magazine Nearly Torpedoed Jimmy Carter’s Presidential Campaign

The pious Georgia Democrat spoke earnestly of his views on sex, a bridge too far for an emerging behemoth voting bloc: conservative Christians

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/37/483738de-c51e-4f17-90c6-4f41f90b38a2/gettyimages-164404517.jpg)

After signing the landmark civil rights bill into law in 1964, President Lyndon Johnson made a famous prophesy about the future of the Democratic Party: “We have lost the South for a generation.” Since 1956 (and only rarely before), the Republicans—the “Party of Lincoln”—had struggled to win any electoral votes from a state south of the Mason-Dixon line. Then the G.O.P. nominated Senator Barry Goldwater, who had voted against the civil rights bill and proceeded to win Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and South Carolina. LBJ’s predication was proving out, which it did again in 1968, when Richard Nixon inaugurated what became known as a “Southern Strategy.” Democrats won only Texas among the states of the Old Confederacy—and in 1972, lost them all.

The next presidential election, though, the Democrats threw a curveball: they nominated Jimmy Carter, the former governor of Georgia—and pundits began talking about the Republicans’ Southern Strategy as thing of the past.

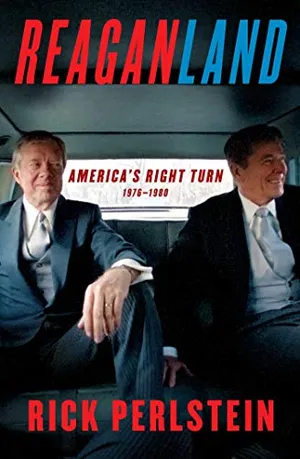

Reaganland: America's Right Turn 1976-1980

Backed by a reenergized conservative Republican base, Reagan ran on the campaign slogan “Make America Great Again”—and prevailed. Reaganland is the story of how that happened, tracing conservatives’ cutthroat strategies to gain power and explaining why they endure four decades later.

Politics, however, is rarely so simple. One of the things that made Carter such a remarkable politician in 1976 was his ability to attract the loyalty of so many different classes of voters—some of them from constituencies traditionally opposed to one another. President Gerald Ford’s adman Mal MacDougall tells a story in his campaign memoir about the first strategy briefing he attended with Ford’s brilliant and innovative pollster, Robert Teeter. One of his innovations was something called a “perceptual map”: a series of acetate sheets with dots printed upon them, each sheet representing a different voting bloc, each point a surveyed voter.

Teeter began slowly laying sheets on top of one another:

Thousands of little dots began to cluster around Jimmy Carter. Blue-collar workers started clinging to the Carter circle. Intellectuals gathered around him. Catholics and Jews…Blacks and Chicanos smothered him with their dots. People who care about busing dropped at his feet. People who were for gun control sided with him as well. Conservative women kissed his feet. Liberal women hugged his head. Environmentalists swarmed around him. The Rich touched him. The poor clung to him.

The Ford people emerged terrified; terrified, too, about a new political constituency that Carter, a devout Southern Baptist, was bringing to the table. Evangelical Christians, traditionally chary of getting involved in partisan politics. “It could be the most powerful force ever harvested,” Teeter said at that meeting. “They’ve got an underground communications network. And Jimmy Carter is plugged right into it.”

Then history, as it likes to do, threw a spanner into the works.

That summer, for a magazine article, Carter had sat for a series of wide-ranging interviews that formed perhaps the richest document of a presidential nominee’s thinking in the history of American electioneering. The candidate was strikingly self-reflective, unusually open in taking on sacred cows, frank in acknowledging America’s faults. He aired his self-doubts, his fears—but also, bracingly, his lack of fear regarding one subject in particular: the possibility of his own death by assassination. The reason, he said, was his Christian faith—which led to a long and searching theological discussion that culminated in an observation, in explaining the Christian concept of sin and redemption, that God had forgiven him even though he had committed “lust in his heart.” And because it appeared in the November issue of the soft-core pornography publication Playboy, Carter’s reference to sex became all anyone could talk about.

The interview shifted the entire dynamic of the election—and helped get the Republican Southern Strategy back on track for all the time to come, only now with religion, not racial integration, as its most conspicuous vector. “Four months ago most for the people I knew were pro-Carter,” one of Carter’s fellow Southern Baptists, the television preacher Jerry Falwell, told the Washington Post several weeks later. “Today, that has totally reversed.”

The reversal didn’t happen on its own.

One group of Evangelicals, the Christian Freedom Foundation, were already convinced that Carter had never truly been one of them because of his association with the iniquities of liberalism. The organization, founded by leading conservative Christians, distributed 120,000 recruitment mailings to ministers that included a book called The Five Duties of a Christian Citizen and a manual on how to elect “real Christians” to office. The manual proposed screening candidates for endorsement with the question, “How do you feel about Nelson Rockefeller or Ronald Reagan as presidential candidates?” A preference for Rockefeller, Ford’s vice president and the tribune of the Republicans’ liberal wing, was disqualifying.

The Carter campaign, meanwhile, was busy reaching out to voters from feminists to union members to environmentalists—and Playboy readers; it took evangelicals for granted. Ford, for his part, a staid Episcopalian, was reluctant to talk about faith, delegating the task to surrogates like his seminarian son, Mike, who said, “Jimmy Carter wears his religion on his sleeve but Jerry Ford wears it in his heart.”

Now, however, Ford stuck his finger in the wind, and decided to give wearing his faith on his sleeve a shot. The maneuver coincided with a pivot in his campaign’s electoral calculations. Ford strategists had originally planned to concentrate on states like New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Illinois—the “big industrial states of the North,” in the political reporters’ cliché. Then they changed their mind, realizing that they could win more electoral votes by looking South. The “big industrial states” were no longer, comparatively, so big. In 1948, the year Ford was first elected to Congress, New York cast 47 electoral votes; in 1976, it had 41. In those same years Florida’s electoral votes doubled. As an electoral phenomenon, the “Sunbelt”—parts of which used to be called the “Bible Belt”—had arrived.

On September 22, the day after the Playboy interview was distributed to media, Ford hosted 34 evangelical leaders in the White House Cabinet Room. The most prominent, W.S. “Wally” Criswell, was later described by Falwell as America’s “Protestant pope of this generation.” Like many fundamentalist pastors now dipping their toe into electoral politics, Criswell, the pastor of the massive First Baptist Church in Dallas, was a former segregationist. After the Supreme Court handed down its decision in Brown v. Board of Education, he gave a widely circulated sermon labeling activists for racial integration “a bunch of infidels, dying from the neck up,” preaching that “the idea of the universal brotherhood and the fatherhood of God is a denial of everything in the Bible.” In 1960, Criswell came to national attention leading a day of prayer against the possibility of a Catholic acceding to the White House—“the death of a free church in a free state and our hopes of continuance of full religious liberty in America.” By 1972, he had come around on integration, but was so angry at Richard Nixon’s ongoing to Communist China that the President invited him the White House to talk him down.

Now, in 1976, he was back—hosted by a president whose wife, Betty, he had recently savaged for supporting legalized abortion and taking in stride the idea of her teenage daughter having a premarital affair: “a gutter-type mentality,” “animal thinking.” But after Ford explained to him and his brethren that religion had “a tremendous subjective impact” on his White House decision-making, and spoke of his “deep concern about the rising tide of secularism,” and said he and Betty read the Bible each night, Criswell proved impressed, and decided to invite the president to pray at his church.

Texas had only added three electoral votes since 1948, but—with its former Democratic governor John Connally leading the way by flamboyantly becoming a Republican in the middle of Watergate—held the most promise of all the states in the South for shifting from its traditional Democratic loyalties on a permanent basis. Ford strategists scheduled a tour of the Lone Star State for the second week in October. Southern Strategy 2.0 now dawned, with Reverend Criswell’s giant red-brick church was the first stop.

The interior was festooned with banners depicting Revolutionary War soldiers and bicentennial 13-star flags. Criswell’s hair was slicked back; he wore a cream-colored suit. He regaled his congregation with the story of his White House visit: “Mr. President,” he recalled asking, “if Playboy magazine were to ask you for an interview, what would you do?” Ford replied, “I was asked by Playboy magazine for an interview, and I declined with an emphatic ‘No’!” Six thousand worshipers broke into a torrent of applause.

Criswell berated Carter for saying in another interview that he was considering removing tax-exempt status from church businesses like radio stations, TV programs, colleges and publishing companies. Criswell said reading about that interview brought “dread and foreboding to my deepest soul. […] To tax any of them is to tax the church ... leading to the possibility of our destruction. […] I hear Gerald Ford, our president, say boldly and courageously that he would interdict any such movement in America. May the Lord give him strength!” (Two years later, fears that Carter’s IRS commissioner might remove tax-exempt status from Christian schools became the most galvanizing single factor in recruiting more pastors to the religious right.)

The president, sitting beside what the pool reporter called “a full orchestra larger than most Broadway pit orchestras,” beamed. The choir broke into Handel’s “Worthy Is the Lamb.” Criswell, described in the pool report as “organ-lunged,” remarked, “I think if Handel looked down from heaven, he would be proud of this choir and this orchestra. And Mr. President, that’s why the White House ought to be in Dallas, Texas, instead of Washington.” He described a speech President Ford gave to the Southern Baptist Convention as “one of the most moving and masterful addresses I have ever heard in my life.” Theatrically dabbing a tear from his eye, he described Ford’s seminarian son as “a sweet humble boy.” Then he called his White House visit “one of the highest days of my life.” The pair made their way down the aisle and out onto the church steps, where one of the waiting reporters asked if this meant the pastor was making a presidential endorsement. “Yes,” he said. “I am for him. I am for him.” The appearance was edited into a campaign commercial.

These seeds had no yet ripened for harvest by November. Jimmy Carter squeaked by in Texas, by three points, and in the electoral college by 57 votes. Pundits said a major reason Ford wasn’t able to beat Carter in states like Texas and Mississippi—with enough electoral votes between them for victory—was conservative hero and former California governor Ronald Reagan’s reluctance to campaign for the ticket. Four years later, though, Reagan was the nominee, the majority of evangelicals judged Jimmy Carter something like an infidel, and, lo, forevermore, Southern Strategy 2.0 has enjoyed everlasting life.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.