Ireland’s Forgotten Sons Recovered Two Centuries Later

In Pennsylvania, amateur archaeologists unearth a mass grave of immigrant railroad workers who disappeared in 1832

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Digs-Ireland-Duffys-cut-gravesite-631.jpg)

Buried in a green Pennsylvania valley for nearly two centuries, the man had been reduced to a jumble of bones: skull, vertebrae, toes, teeth and ribs. Gradually, though, he came alive for William and Frank Watson, twin brothers who are leading an excavation at a pre-Civil War railroad construction site outside Philadelphia, where 57 Irish workers are said to have been surreptitiously interred in a mass grave.

The plates of the man’s skull were not fully fused, indicating he was a teenager when he died. He was relatively short, 5-foot-6, but quite strong, judging from his bone structure. And X-rays showed he never grew an upper right first molar, a rare genetic defect. The Watsons have tentatively identified him as John Ruddy—an 18-year-old laborer from rural County Donegal, who sailed from Derry in the spring of 1832. He likely had cholera, alongside dozens of his countrymen, all dying within two months of setting foot on American shores.

Tipped off by a long-secret railroad company document, the Watsons searched the woods around Malvern, Pennsylvania, for four and a half years to find “our men” (as they call the workers) before locating the Ruddy skeleton in March 2009. They have since unearthed the mingled remains of several others and believe they know the location of the rest. William is a professor of medieval history at Immaculata University; Frank is a Lutheran minister. Both belong to Irish and Scottish cultural societies (they are competitive bagpipers), but neither had any prior archaeological training.

“Half the people in the world thought we were crazy,” William says.

“Every once in a while we would sit down and ask ourselves: ‘Are we crazy?’” Frank adds. “But we weren’t.”

Today their dig is shedding light on the early 19th century, when thousands of immigrants labored to build the infrastructure of the still-young nation. Labor unions were in their infancy. Working conditions were controlled entirely by the companies, most of which had little regard for the safety of their employees. The Pennsylvania grave was a human “trash heap,” Frank says. Similar burial sites lie alongside this country’s canals, dams, bridges and railroads, their locations known and unknown; their occupants nameless. But the Watsons were determined to find the Irishmen at the site, known as Duffy’s Cut. “They’re not going to be anonymous anymore,” William says.

The project began in 2002 when the Watsons began reviewing a private railroad company file that had belonged to their late grandfather, the assistant to Martin Clement, a 1940s-era Pennsylvania Railroad president. The file—a collection of letters and other documents Clement assembled during a 1909 company investigation—described an 1832 cholera outbreak that swept through a construction encampment along a stretch of railroad that would connect Philadelphia with Columbia, Pennsylvania. Contemporary newspapers, which usually kept detailed tallies of local cholera fatalities, implied that only a handful of men had died at the camp. Yet Clement’s inquiry concluded that at least 57 men had perished. The Watsons became convinced the railroad covered up the deaths to ensure the recruitment of new laborers.

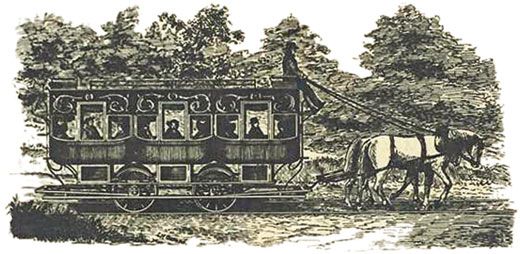

Work on the Philadelphia and Columbia line, originally a horse-drawn train, began in 1828. Three years later, a contractor named Philip Duffy got the nod to construct Mile 59, one of the toughest stretches. The project required leveling a hill—known as making a cut—and using the soil to fill in a neighboring valley in order to flatten the ground. It was nasty work. The dirt was “heavy as the dickens,” says railroad historian John Hankey, who visited the site. “Sticky, heavy, a lot of clay, a lot of stones—shale and rotten rock.”

Duffy, a middle-class Irishman, had tackled previous railroad projects by enlisting “a sturdy looking band of the sons of Erin,” an 1829 newspaper article reported. By 1830, census records show that Duffy was sheltering immigrants in his rental home. Like many laborers from Ireland’s rural north, Duffy’s workers were probably poor, Catholic and Gaelic-speaking. Unlike the wealthier Scotch-Irish families who preceded them, they were typically single men traveling with few possessions who would perform punishing jobs for a pittance. The average wages for immigrant laborers were “ten to fifteen dollars a month, with a miserable lodging, and a large allowance for whiskey,” the British novelist Frances Trollope reported in the early 1830s.

When cholera swept the Philadelphia countryside in the summer of 1832, railroad workers housed in a shanty near Duffy’s Cut fled the area, according to Julian Sachse, a historian who interviewed elderly locals in the late 1800s. But nearby homeowners, perhaps fearful of infection (it was not yet known that cholera spreads through contaminated water sources), turned them away. The laborers went back to the valley, to be tended only by a local blacksmith and nuns from the Sisters of Charity, who went to the camp from Philadelphia. Later the blacksmith buried the bodies and torched the shanty.

That story was more legend than history in August 2004 when the Watsons began digging along Mile 59, near modern Amtrak tracks. (They’d obtained permission from local homeowners and the state of Pennsylvania to excavate.) In 2005, Hankey visited the valley and guessed where the workers would have strung their canvas shelter: sure enough, the diggers found evidence of a burned area, 30 feet wide. Excavations turned up old glass buttons, pieces of crockery and clay pipes—including one stamped with the image of an Irish harp.

But no bodies. Then Frank Watson reread a statement in the Clement file from a railroad employee: “I heard my father say that they were buried where they were making the fill.” Was it possible the bodies lay beneath the original railroad tracks? In December 2008, the Watsons asked geoscientist Tim Bechtel to concentrate his ground-penetrating radar search along the embankment, where he detected a large “anomaly,” possibly an air pocket formed by decomposed bodies. Three months later, shortly after St. Patrick’s Day, a student worker named Patrick Barry struck a leg bone with his shovel.

On a recent afternoon, the valley was quiet, except for the scrape and clatter of shovels, the slap of wet dirt in the bottom of a wheelbarrow, and every now and then the shuddering shriek of a passing train. The terrain would challenge even professional excavators: the embankment is steep and the roots of a huge tulip poplar have fingered their way through the site. The team’s pickaxes and spades are not much more sophisticated than the Irishmen’s original tools. “We are unbuilding what they died to build,” William Watson says.

The Watson brothers hope to recover every last body. In doing so, they could provoke fresh controversies. Some of the men might have been murdered, says Janet Monge, a University of Pennsylvania forensic anthropologist who is analyzing the remains. At least one and perhaps two of the recovered skulls show signs of trauma at the time of death, she says, adding these may have been mercy killings, or perhaps local vigilantes didn’t want more sick men leaving the valley.

Identifying the bodies is a challenge, because the laborers’ names are absent from census records and newspaper obituaries. And, says William Watson, the archives of the Sisters of Charity offer only a “spotty” account. The most promising clue is the passenger list of a ship, the John Stamp, the only vessel in the spring of 1832 to come from Ireland to Philadelphia with a good many Irish laborers aboard—including a teenager, John Ruddy of Donegal. Many of these immigrants did not show up in subsequent census records.

The news media in Ireland have reported on the Duffy’s Cut dig since 2006. This past year, as word of the discovery of the skeleton of Ruddy made headlines, the Watsons received phone calls and e-mails from several Ruddys in Ireland, including a Donegal family whose members exhibit the same congenital defect found in the skeleton. Matthew Patterson, a forensic dentist who worked with the Watsons, says the genetic abnormality is “exceptionally rare,” appearing in perhaps one in a million Americans, though the incidence may be greater in Ireland.

The Watsons are confident they have found the family John Ruddy left behind nearly two centuries ago. But to be certain, the brothers are raising money for genetic tests to compare DNA from the skeleton with that of the Donegal Ruddys; if there’s a match, Ruddy’s remains will be sent back to Ireland for a family burial. Any unclaimed remains the Watsons disinter will be buried beneath a Celtic cross in West Laurel Hill cemetery, where they will rest alongside some of Philadelphia’s great industrial tycoons. In the meantime, the Watsons held their own impromptu memorial service, going down to the mass grave one June afternoon to play the bagpipes.

Staff writer Abigail Tucker reported on the excavation of a Virginia slave jail in the March 2009 issue.