Is the New Tonto Any Better Than the Old Tonto?

A new film revives The Lone Ranger, but has it eliminated the TV series’ racist undertones

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/National-Treasure-Lone-Ranger-mask-631.jpg)

Just before the closing credits came the question, which has echoed through the decades. The desperadoes have been marched off to the hoosegow. The victim, untied, dusts herself off and looks wistfully at the man riding away on a white horse, and asks: Who was that masked man?

It’s a question we’ll be hearing a lot this summer, as The Lone Ranger bursts onto screens in pinwheels of exploding railroad trestles and hurtling locomotives. The Disney production is a fascinating study in how tastes and values have changed since the hit TV series of the 1950s. The moviemakers seem to have lost interest in horses, presumably because they don’t blow up when they crash; judging from the trailers, the Lone Ranger’s signature cry of “Hi-yo Silver” might as well be “all aboard.” More significantly, the ads give equal billing to two stars, but one of them, Johnny Depp, is a much bigger name than the other, Armie Hammer. Hammer, who played the Winklevoss twins in The Social Network, is the Lone Ranger. Depp was cast as Tonto.

The studio, which announced a $1,000-a-ticket premiere to benefit the American Indian College Fund, has obviously considered the political implications of making a movie in 2013 in which the Native American figure is an inscrutable sidekick. Depp has said he wanted to restore some integrity to the Tonto character, “to try, in my own small way, to right the many wrongs that have been done” by Hollywood’s portrayals of Indians, which were insensitive even in comparison to the industry’s treatment of other ethnic minorities.

Whether Depp’s intentions will mollify critics of the film, who were out in force even before it was released, remains to be seen. Adrienne Keene, a Harvard graduate student and member of the Cherokee Nation, who runs a blog called “Native Appropriations,” said she initially was unhappy the filmmakers didn’t come up with an Indian actor to play Tonto. Depp, like many white Americans, claims some Indian ancestry, though he does not self-identify as such. But after seeing Depp’s makeup (his face is streaked with black and white paint) and headdress (a spread-winged, intact taxidermy crow), Keene says she’s glad an Indian isn’t playing the role, which she calls “extremely stereotypical.”

Although Tonto’s grammar has improved greatly since the “Me go now” dialogue of 60 years ago, Depp still reads his lines in the sententious, wisdom-of-the-elders cadences that Indians call “Tonto-speak.” “He could have treated the Tonto-speak as a joke, like the spirit-talk and the funny hat,” muses Theodore C. Van Alst Jr., director of the Native American Cultural Center at Yale. “In 2013, that could work. But by playing it straight, he gives the impression that Indians really were like that. And I’m afraid that Tonto is the only Indian most Americans will ever see.”

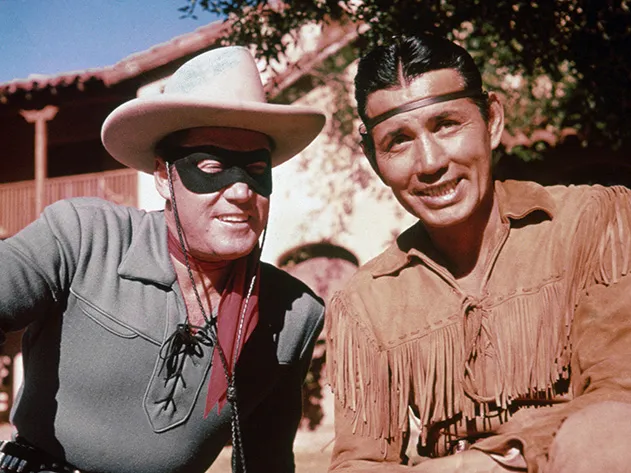

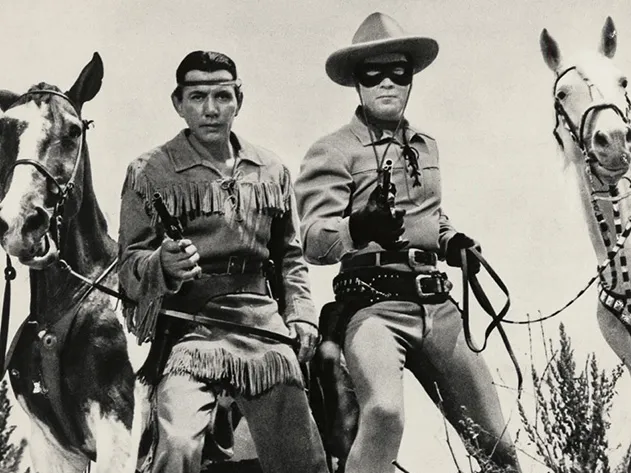

If he’s right, the movie might be a big missed opportunity, since “Tonto,” to Native Americans, is synonymous with ugly caricature. The word, which has no known meaning in any Native American language, means “stupid” in Spanish. And yet the character Tonto is a noble figure, even as a sidekick, brave and loyal and resourceful. The Indian actor Jay Silverheels played him with remarkable dignity on television, considering the material. In the pilot episode, Tonto rescues the Texas Ranger who is the lone survivor of an ambush by an outlaw gang. Tonto makes the mask, to conceal the man’s identity from the bandits who think he’s dead, and gives him a name: Lone Ranger.

The mask is now a venerated icon of 1950s pop culture, right up there with Mousketeer ears. One sold at auction for $33,000; another, worn by the actor Clayton Moore in personal appearances after the series, is in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, a gift of his daughter, Dawn. (Moore died in 1999 at the age of 85.) The original mask was purple felt, a color that showed up better on the black-and-white screens of the day, and was annoyingly hot to wear on location under the desert sun, according to Moore’s memoir, I Was That Masked Man.

Other crime-fighters, like Zorro and Batman, disguised themselves to distinguish their heroic personas from their everyday ones. The Lone Ranger was only ever himself; his real name (John Reid) was hardly ever spoken. From behind the eye slits he warily surveyed a frontier world of bank robbers and kidnappers and confidence men. With his uncanny ability to aim a six-shooter from a galloping horse, he winged his quarry in the gun hand, because it wasn’t his prerogative to end the life of even a lowdown card cheat, the precious silver bullets serving to remind him of the high cost of firing at a man. Long ago, the laconic, self-effacing Lone Ranger ceded the defense of law and order to swaggering, self-aggrandizing bullies like Dirty Harry, but we still are drawn to him, drawn by our need for a hero from a simpler time to wonder about the man behind the mask.