Islam’s Medieval Underworld

In the medieval period, the Middle East was home to many of the world’s wealthiest cities—and to a large proportion of its most desperate criminals

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130722123136baghdad-470.jpg)

The year is—let us say—1170, and you are the leader of a city watch in medieval Persia. Patrolling the dangerous alleyways in the small hours of the morning, you and your men chance upon two or three shady-looking characters loitering outside the home of a wealthy merchant. Suspecting that you have stumbled across a gang of housebreakers, you order them searched. From various hidden pockets in the suspects’ robes, your men produce a candle, a crowbar, stale bread, an iron spike, a drill, a bag of sand—and a live tortoise.

The reptile is, of course, the clincher. There are a hundred and one reasons why an honest man might be carrying a crowbar and a drill at three in the morning, but only a gang of experienced burglars would be abroad at such an hour equipped with a tortoise. It was a vital tool in the Persian criminals’ armory, used—after the iron spike had made a breach in a victim’s dried-mud wall—to explore the property’s interior.

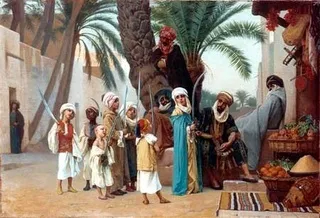

We know this improbable bit of information because burglars were members of a loose fraternity of rogues, vagabonds, wandering poets and outright criminals who made up Islam’s medieval underworld. This broad group was known collectively as the Banu Sasan, and for half a dozen centuries its members might be encountered anywhere from Umayyad Spain to the Chinese border. Possessing their own tactics, tricks and slang, the Banu Sasan comprised a hidden counterpoint to the surface glories of Islam’s golden age. They were also celebrated as the subjects of a scattering of little-known but fascinating manuscripts that chronicled their lives, morals and methods.

According to Clifford Bosworth, a British historian who has made a special study of the Banu Sasan, this motley collection of burglars’ tools had some very precise uses:

The thieves who work by tunneling into houses and by murderous assaults are much tougher eggs, quite ready to kill or be killed in the course of their criminal activities. They necessarily use quite complex equipment… are used for the work of breaking through walls, and the crowbar for forcing open doors; then, once a breach is made, the burglar pokes a stick with a cloth on the end into the hole, because if he pokes his own head through the gap, might well be the target for the staff, club or sword of the houseowner lurking on the other side.

The tortoise is employed thus. The burglar has with him a flint-stone and a candle about as big as a little finger. He lights the candle and sticks it on the tortoise’s back. The tortoise is then introduced through the breach into the house, and it crawls slowly around, thereby illuminating the house and its contents. The bag of sand is used by the burglar when he has made his breach in the wall. From this bag, he throws out handfuls of sand at intervals, and if no-one stirs within the house, he then enters it and steals from it; apparently the object of the sand is either to waken anyone within the house when it is thrown down, or else to make a tell-tale crushing noise should any of the occupants stir within it.

Also, the burglar may have with him some crusts of dry bread and beans. If he wishes to conceal his presence, or hide any noise he is making, he gnaws and munches at these crusts and beans, so that the occupants of the house think that it is merely the cat devouring a rat or mouse.

As this passage hints, there is much about the Banu Sasan that remains a matter of conjecture. This is because our knowledge of the Islamic underworld comes from only a handful of surviving sources. The overwhelming mass of Arabic literature, as Bosworth points out, “is set in a classical mold, the product of authors writing in urban centers and at courts for their patrons.” Almost nothing written about daily life, or the mass of the people, survives from earlier than the ninth century (that is, the third century AH), and even after that date the information is very incomplete.

It is not at all certain, for example, how the Banu Sasan came by their name. The surviving sources mention two incompatible traditions. The first is that Islamic criminals were considered to be followers—”sons”— of a (presumably legendary) Sheikh Sasan, a Persian prince who was displaced from his rightful place in the succession and took to living a wandering life. The second is that the name is a corrupted version of Sasanid, the name of the old ruling dynasty of Persia that the Arabs destroyed midway through the seventh century. Rule by alien conquerors, the theory goes, reduced many Persians to the level of outcasts and beggars, and forced them to live by their wits.

There is no way now of knowing which of these tales, if either, is rooted in truth. What we can say is that the term “Banu Sasan” was once in widespread use. It crops up to describe criminals of every stripe, and also seems to have been acknowledged, and indeed used with pride, by the villains of this period.

Who were they, then, these criminals of Islam’s golden age? The majority, Bosworth says, seem to have been tricksters of one sort or another,

who used the Islamic religion as a cloak for their predatory ways, well aware that the purse-strings of the faithful could easily be loosed by the eloquence of the man who claims to be an ascetic or or mystic, or a worker of miracles and wonders, to be selling relics of the Muslim martyrs and holy men, or to have undergone a spectacular conversion from the purblindness of Christianity or Judaism to the clear light of the faith of Muhammad.

Amira Bennison identifies several adaptable rogues of this type, who could “tell Christian, Jewish or Muslim tales depending on their audience, often aided by an assistant in the audience who would ‘oh’ and ‘ah’ at the right moments and collect contributions in return for a share of the profits,” and who thought nothing of singing the praises of both Ali and Abu Bakr—men whose memories were sacred to the Shia and the Sunni sects, respectively. Some members of this group would eventually adopt more legitimate professions—representatives of the Banu Sasan were among the first and greatest promoters of printing in the Islamic world—but for most, their way of life was something they took pride in. One of the best-known examples of the maqamat (popular) literature that flourished from around 900 tells the tale of Abu Dulaf al-Khazraji, the self-proclaimed king of vagabonds, who secured a tenuous position among the entourage of a 10th-century vizier of Isfahan, Ibn Abbad, by telling sordid, titillating, tales of the underworld.

“I am of the company of beggar lords,” Abu Dulaf boasts in one account,

the cofraternity of the outstanding ones,

One of the Banu Sasan…

And the sweetest way of life we have experienced is one spent in sexual indulgence and wine drinking.

For we are the lads, the only lads who really matter, on land and sea.

In this sense, of course, the Banu Sasan were merely the Middle Eastern equivalents of rogues who have always existed in every culture and under the banner of every religion; Christian Europe had equivalents enough, as Chaucer’s Pardoner can testify. Yet the criminals produced by medieval Islam seem to have been especially resourceful and ingenious.

Ismail El Outamani suggests that this was because the Banu Sasan were a product of an urbanization that was all but unknown west of Constantinople at this time. The Abbasid caliphate’s capital, Baghdad, had a population that peaked at perhaps half a million in the days of Haroun al-Rashid (c.763-809), the sultan depicted in the Thousand and One Nights–large and wealthy enough to offer crooks the sort of wide variety of opportunities that encouraged specialization. But membership of the fraternity was defined by custom as much as it was by criminal inclination; poets, El Outmani reminds us, literally and legally became rogues whenever a patron dispensed with their services.

While most members of the Banu Sasan appear to have lived and worked in cities, they also cropped up in more rural areas, and even in the scarcely populated deserts of the region. The so-called prince of camel thieves, for instance—one Shaiban bin Shihab—developed the novel technique of releasing a container filled with voracious camel ticks on the edges of an encampment. When the panicked beasts of burden scattered, he would seize his chance and steal as many as he could. To immobilize any watchdogs in the area, other members of the Banu Sasan would “feed them a sticky mixture of oil-dregs and hair clippings”—the contemporary writer Damiri notes—”which clogs their teeth and jams up their jaws.”

The best-known of the writers who describe the Banu Sasan is Al-Jahiz, a noted scholar and prose stylist who may have been of Ethiopian extraction, but who lived and wrote in the heartland of the Abbasid caliphate in the first half of the ninth century. Less well known, but of still greater importance, is the Kashf al-asrar, an obscure work by the Syrian writer Jaubari that dates to around 1235. This short book—the title can be translated as Unveiling of Secrets—is in effect a guide to the methods of the Banu Sasan, written expressly to put its readers on guard against tricksters and swindlers. It is a mine of information concerning the methods of the Islamic underworld, and is plainly the result of considerable research; at one point Jaubari tells us that he studied several hundred works in order to produce his own; at another, he notes that he has uncovered 600 stratagems and tricks used by housebreakers alone. In all, Jaubari sets out 30 chapters’ worth of information on the methods of everyone from crooked jewelers—whom he says had 47 different ways of manufacturing false diamonds and emeralds—to alchemists with their “300 ways of dakk” (falsification). He details the way in which money-changers wore magnetized rings to deflect the indicator on their scales, or used rigged balances filled with mercury, which artificially inflated the weight of the gold that was placed on them.

Our sources are united in suggesting that a large proportion of the Banu Sasan were Kurds, a people seen by other Middle Eastern peoples as brigands and predators. They also show that the criminal slang they employed drew on a wide variety of languages. Much of it has its origins in what Johann Fück has termed “Middle Arabic,” but the remainder seems to be derived from everything from Byzantine Greek to Persian, Hebrew and Syriac. This is a useful reminder not only of what a cosmopolitan place western Asia was during the years of the early Islamic ascendancy, but also that much criminal slang has its origins in the requirement to be obscure—most obviously because there is often an urgent need to hide what was being discussed from listeners who might report the speakers to the police.

Ultimately, however, what strikes one most about the Banu Sasan is their remarkable inclusiveness. At one extreme lie the men of violence; another of Bosworth’s sources, ar-Raghib al-Isfahani, lists five separate categories of thug, from the housebreaker to out-and-out killers such as the sahib ba’j, the “disemboweler and ripper-open of bellies,” and the sahib radkh, the “crusher and pounder” who accompanies lone travelers on their journeys and then, when his victim has prostrated himself in prayer, “creeps up and hits him simultaneously over the head with two smooth stones.” At the other lie the poets, among them the mysterious Al-Ukbari—of whom we are told little more than that he was “the poet of rogues, their elegant exponent and the wittiest of them all.”

In his writings, Al-Ukbari frankly admitted that he could not “earn any sort of living through philosophy or poetry, but only through trickery.” And among the meager haul of 34 surviving stanzas of his verse can be found this defiant statement:

Nevertheless I am, God be praised,

A member of a noble house,

Through my brethren the Banu Sasan,

The influential and bold ones…

When the roads become difficult for both

The night travelers and the soldiery, on the alert against their enemies,

The Bedouins and the Kurds,

We sail forward along that way, without

The need of sword or even of scabbard,

And the person who fears his foes seeks

Refuge by means of us, in his terror.

Sources Amira Bennison. The Great Caliphs: the Golden Age of the ‘Abbasid Empire. London: IB Tauris, 2009; Clifford Bosworth. The Medieval Islamic Underworld: The Banu Sasan in Arabic Society and Literature. Leiden, 2 vols.: E.J. Brill, 1976; Richard Bullet. What Life Was Like in the Lands of the Prophet: Islamic World, AD570-1405. New York: Time-Life, 1999; Ismail El Outmani. “Introduction to Arabic ‘carnivalised’ literature.” In Concepción Vázquez de Benito & Miguel Ángel Manzano Rodríguez (eds). Actas XVI Congreso Ueai. Salamanca: Gráficas Varona, nd (c.1995); Li Guo. The Performing Arts in Medieval Islam: Shadow Play and Popular Poetry in Ibn Daniyal’s Mamluk Cairo. Leiden: Brill, 2012; Ahmad Ghabin. Hjsba, Arts & Crafts in Islam. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 2009; Robert Irwin. The Penguin Anthology of Classical Arabic Literature. London: Penguin, 1999; Adam Sabra. Poverty and Charity in Medieval Islam: Mamluk Egypt, 1250-1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)