The Issue on the Table: Is “Hamilton” Good For History?

In a new book, top historians discuss the musical’s educational value, historical accuracy and racial revisionism

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/b3/68b3f25b-70c9-4e21-b6ce-c254758921d5/fx15px.jpg)

Even if it hadn’t won big at the 2016 Tony Awards, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton: An American Musical would remain a theatrical powerhouse and a fixture of contemporary American culture. It’s likewise been seen as a champion of U.S. history, inspiring Americans young and old to learn more about their founding fathers, particularly the “forgotten” Alexander Hamilton.

Professional historians are no exception to getting wrapped up in the excitement created by Hamilton, and they’ve begun to wonder what impact the show will have on history as an academic discipline. Though Miranda has said in interviews that he “felt an enormous responsibility to be as historically accurate as possible,” his artistic representation of Hamilton is necessarily a work of historical fiction, with moments of imprecision and dramatization. The wide reach of Miranda’s work begs the question of historians: is the inspirational benefit of this cultural phenomenon worth looking past its missteps?

Historians Renee Romano of Oberlin College and Claire Bond Potter of the New School in New York capture this debate in their new volume Historians on Hamilton: How a Blockbuster Musical is Restaging America’s Past, a collection of 15 essays by scholars on the historical, artistic and educational impact of the musical. Romano, who hatched the idea for the book, says she was inspired by “the flurry of attention and conversation among historians engaging with [Hamilton], who really had very divergent opinions on the quality, the work it was doing, the importance of it, the messages it was sending.”

“There’s a really interesting conversation brewing here that would be great to bring to a larger public,” says Romano.

While none of the book’s contributors question the magnitude of Hamilton as a cultural phenomenon, many challenge the notion that the show singlehandedly brought about the current early American history zeitgeist. In one essay, the City University of New York's David Waldstreicher and the University of Missouri's Jeffrey Pasley suggest that Hamilton is just one more installment in the recent trend of revisionist early American history that troubles modern historians. They argue that since the 1990s, “Founders Chic” has been in vogue, with biographers presenting a character-driven, nationalist and “relatable” history of the Founding Fathers that they criticize as overly complimentary. The “Founders Chic” genre, they say, came into its own in 2001 with the publication of John Adams by David McCullough, and Founding Brothers by Joseph Ellis, the latter of which they especially criticize for inflating the moral rectitude of their subject and “equating the founding characters with the U.S. nation-state.”

Historians on Hamilton: How a Blockbuster Musical Is Restaging America's Past

America has gone "Hamilton" crazy. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Tony-winning musical has spawned sold-out performances, a triple platinum cast album, and a score so catchy that it is being used to teach U.S. history in classrooms across the country. But just how historically accurate is "Hamilton?" And how is the show itself making history?

According to Potter, this increased focus on early American history stemmed from worries about current political turbulence. “By the 1990s, politics in the United States are actually kind of falling apart,” she says. “We have the culture wars, we have the shift of conservatives into the Republican Party. There is increasing populism in the Republican party and increasing centrism in the Democratic party. In other words, politics are really in flux.”

“One response to that is to say, ‘What is this country about?’ And to go back to the biographies of the founding fathers,” she explains.

Author William Hogeland similarly observes the current bipartisan popularity of the Founding Fathers, as intellectuals from the left and the right find reasons to claim Hamilton as their own. According to Hogeland, the intellectual Hamilton craze can be traced back to buzz in certain conservative-leaning political circles in the late ’90s, with various op-eds at the time lauding Hamilton’s financial politics as the gold standard of balanced conservatism. Hamilton’s modern popularity surged with the Ron Chernow biography that ultimately inspired Miranda, but Hogeland says that Chernow, and in turn Miranda, fictionalize Hamilton by overemphasizing his “progressive rectitude.”

Hogeland especially criticizes Chernow and Miranda’s depiction of Hamilton as a “manumission abolitionist,” or someone who favored the immediate, voluntary emancipation of all slaves. Though Hamilton did hold moderately progressive views toward slavery, it’s likely that he and his family did own household slaves – cognitive dissonance typical of the time that Chernow and Miranda downplay. He laments that the biography and show give “the false impression that Hamilton was special among the founding fathers in part because he was a staunch abolitionist,” continuing that “satisfaction and accessibility pose serious risks to historical realism.”

“As we’ve come more to want to save the founders from that story of the original sin of slavery, we put more emphasis on founding fathers who in some ways raised critique of slavery at the time,” adds Romano.

In the context of the enduring racism in today’s society, Hamilton has made waves given its casting of black and Latino actors as America’s founders. This “race blind” casting has received warm critical acclaim from advocates of racial equality in history and popular culture. “I walked out of the show with a sense of ownership over American history,” said Daveed Diggs, the black actor who played Thomas Jefferson and the Marquis de Lafayette in the original Broadway cast. “Part of it is seeing brown bodies play these people.” As Miranda himself explained, “This is a story about America then, told by America now.”

“It is vital to say that people of color can have ownership over American origin stories… to displace this longstanding connection between true American belonging and whiteness,” says Romano, who focused her own Historians on Hamilton essay around this idea. She details the impact of Hamilton that she has already seen among young people in her own town: “What does it mean to be raising a generation of kids from rural Ohio to think that George Washington could have been black?”

Potter explains that Miranda’s casting decisions constitute an important step in the inclusivity of Broadway as well. “It’s important to think about Hamilton as something that is making a massive intervention into American theater,” she says. “As one of our authors, Liz Wollman, points out, flipped casting is a long tradition in American theater – it’s just that you usually have white people playing people of color. So to flip it in the other direction is something new.”

However, some scholars point out the ironic tension between the musical’s diverse cast and what they see as an overly whitewashed script. Northwestern University‘s Leslie Harris, for example, writes that in addition to the existence of slaves in colonial New York City (none of whom are portrayed in Hamilton), there also was a free black community in the city where African-Americans did serious work toward abolition. To her, excluding these narratives from the show constitutes a missed opportunity, forcing people of color in the cast to promulgate a historical narrative that still refuses to give them a place in it.

Fellow essayist Patricia Herrera of the University of Richmond concurs, worrying that her 10-year-old daughter, who idolizes Angelica Schuyler, might not be able to differentiate between the 18th-century slaveowner and the African-American actress portraying her. “Does the hip-hop soundscape of Hamilton effectively drown out the violence and trauma – and sounds – of slavery that people who looked like the actors in the play might actually have experienced at the time of the nation’s birth?” she writes.

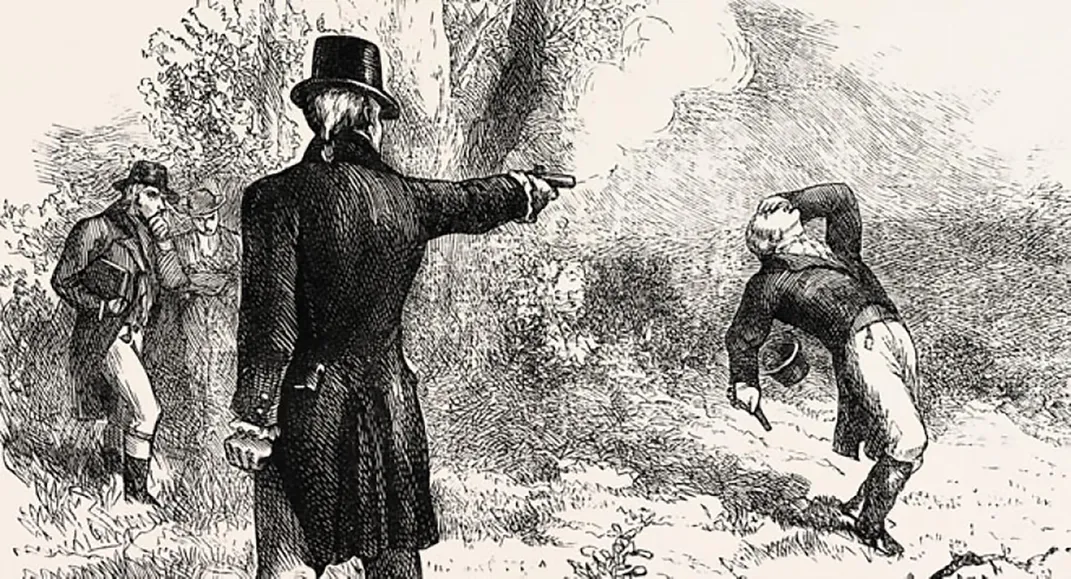

Other historians believe that Hamilton should take these critiques in stride given all that it has accomplished in making this historical study accessible to today’s diverse American society. Joe Adelman of Framingham State University writes that though Hamilton is “not immune from criticism,” it’s important to note that “as a writer of people’s history, Miranda had to find ways to make the story personal for his audience.” He lauds the profundity of Miranda’s scholarship, saying that the ending duel scene in particular “reveals deep research, an understanding of the complexities of evidence, a respect for the historical narrative, and a modern eye that brings fresh vision to the story.” Hamilton’s ability to make this sophisticated research resonate with the public, he says, indicates the show’s ultimate success as a work of historical fiction.

On a personal note, Romano says that this almost ubiquitous appeal of the show has been especially inspirational to her as a professor of history. She recounts how reach of the musical dawned on her when she overheard a group of high school students in her majority white, conservative Ohio town singing songs from the show. “It’s not just a Broadway thing, not just a liberal elite thing,” she remembers thinking. “This is reaching to populations that really go beyond those who typically would be paying attention to those kinds of cultural productions being produced by a liberal from the East Coast.”

To Potter, though, it’s the fact that the Hamilton craze has entered the academic sphere that truly sets the show apart.

“Hamilton has been controversial, certainly around early American historians. There’s a lot of very vigorous discussion about what history represents, and what it doesn’t represent,” says Potter. “It’s important for people to understand that like anything else, Miranda is making an argument about history, and he’s making an argument about the United States. It’s an argument that you can in turn argue with.”

Editor's Note, June 4, 2018: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that David Waldstreicher was from at Temple University and Jeffrey Pasley was from the City University of New York. In fact, Waldstreicher is at the City University of New York and Pasley is at the University of Missouri.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.