J. P. Morgan as Cutthroat Capitalist

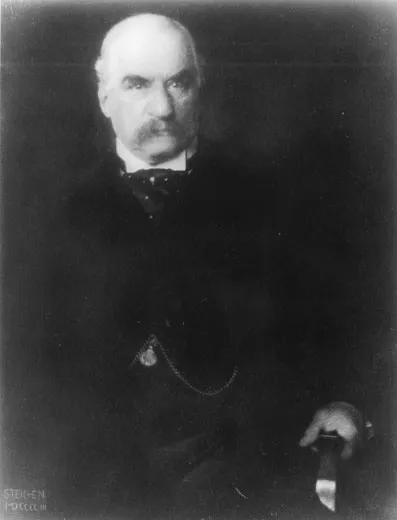

In 1903, photographer Edward Steichen portrayed the American tycoon in an especially ruthless light

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/JP_Morgan631.jpg)

“No price is too great,” John Pierpont Morgan once declared, “for a work of unquestioned beauty and known authenticity.” Indeed, the financier spent half his fortune on art: Chinese porcelains, Byzantine reliquaries, Renaissance bronzes. His London house was so decked out a critic said it resembled “a pawnbrokers’ shop for Croesuses.” Morgan also commissioned a number of portraits of himself—but he was too restless and busy making money to sit still while they were painted.

Which was why, in 1903, the painter Fedor Encke hired a young photographer named Edward Steichen to take Morgan’s picture as a kind of cheat sheet for a portrait Encke was trying to finish.

The sitting lasted just three minutes, during which Steichen took only two photographs. But one of them would define Morgan forever.

In January 1903, Morgan, 65, was at the height of his power, a steel, railroad and electrical-power mogul influential enough to direct huge segments of the American economy. (Four years later he would almost single-handedly quell a financial panic.) Steichen, 23, an immigrant with an eighth-grade education, was working furiously to establish a place in fine-art photography, which was itself struggling to be taken seriously.

Steichen prepared for the shoot by having a janitor sit in for the magnate while he perfected the lighting. Morgan entered, put down his cigar and assumed an accustomed pose. Steichen snapped one picture, then asked Morgan to shift his position slightly. This annoyed him. “His expression had sharpened and his body posture became tense,” Steichen recalled in his autobiography, A Life in Photography. “I saw that a dynamic self-assertion had taken place.” He quickly took a second picture.

“Is that all?” Morgan said. It was. “I like you, young man!” He paid the efficient photographer $500 in cash on the spot.

Morgan’s delight faded when he saw the proofs.

The first shot was innocuous. Morgan ordered a dozen copies; Encke used it to complete an oil portrait in which Morgan looks more like Santa Claus than himself.

But the second image became a sensation. Morgan’s expression is forbidding: his mustache forms a frown, and his eyes (which Steichen later compared to the headlights of an express train) blaze out of the shadows. His face, set off by a stiff white collar, seems almost disembodied in the darkness, though his gold watch chain hints at his considerable girth. In this image, Steichen later said, he only slightly touched up Morgan’s nose, which was swollen from a skin disease. Yet Steichen denied having engineered the image’s most arresting aspect: the illusion of a dagger—actually the arm of the chair—in Morgan’s left hand.

Morgan tore up the proof on the spot.

Steichen, on the other hand, was elated.

“It was the moment when he realized that he had something that would allow him to show his talent to the rest of the world,” says Joel Smith, author of Edward Steichen: The Early Years.

And when the great banker bristled before the photographer’s lens, “Steichen learned something that he never forgot,” says Penelope Niven, author of Steichen: A Biography. “You need to guide or surprise your subject into that revelation of character. You have to get to the essence of that other individual, and you do it at the moment...when the individual is disarmed.”

Yet some critics wonder whether Steichen’s genius lay more in exploiting the public’s prejudices; Americans were deeply resentful of robber barons (just as they tend to resent Wall Street titans today). Smith, for one, believes that no matter how Morgan behaved at the shoot, Steichen intended to reinforce his reputation as a hard-driving capitalist—“someone charging out of the darkness, who embodied aggression and confidence to the point of danger.”

The photograph does reflect aspects of the real man, says Morgan biographer Jean Strouse. “He looks like a well-dressed pirate,” she says. “Photographs don’t lie—there is that in him.”

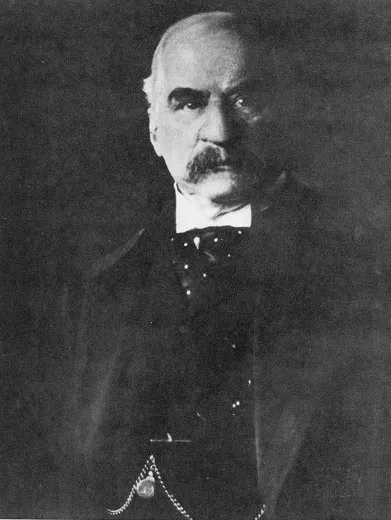

But Morgan was also a man of “many dimensions,” Strouse says—rather shy, in part because of the effect of rhinophyma on his nose. He avoided speaking before crowds and burned many of his letters to protect his privacy. He had a tender side that made him something of a ladies’ man. His love of art was sincere and boundless. And while he profited wildly from the industrializing American economy, he also saw himself as responsible for shepherding it. He functioned as a one-man Federal Reserve until he died, at age 75, in 1913 (the year the central bank was created).

Morgan apparently held no grudge against photographers per se. In 1906, he gave Edward S. Curtis a whopping $75,000 ($1.85 million today) to create a 20-volume photo series on American Indians. And years after the Steichen face-off, Morgan decided that he even liked that second portrait—or at least that he wanted to own it.

“If this is going to be the public image of him, then surely a man who was such a robber baron and so smart about his art collecting and in control of so many fortunes would want to be in control of this,” says photography critic Vicki Goldberg.

Morgan offered $5,000 for the original print, which Steichen had given to his mentor, Alfred Stieglitz; Stieglitz wouldn’t sell it. Steichen later agreed to make a few copies for Morgan but then procrastinated for three years—“my rather childish way,” he later allowed, “of getting even with [him] for tearing up that first proof.”

Staff writer Abigail Tucker also writes about the Renaissance artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo in this issue.