Jane Jetson and the Origins of the “Women Are Bad Drivers” Joke

What happens when a comedy staple of mid-century sitcoms reappears as a late-century Saturday morning tradition?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130214103158jetsons-jane-driving-lesson-470x251.jpg)

This is the 18th in a 24-part series looking at every episode of “The Jetsons” TV show from the original 1962-63 season.

“The problem with these skyways is that by the time they’re built they’re obsolete. This traffic is the worst I’ve seen yet,” George Jetson proclaims as he zips around in his flying car.

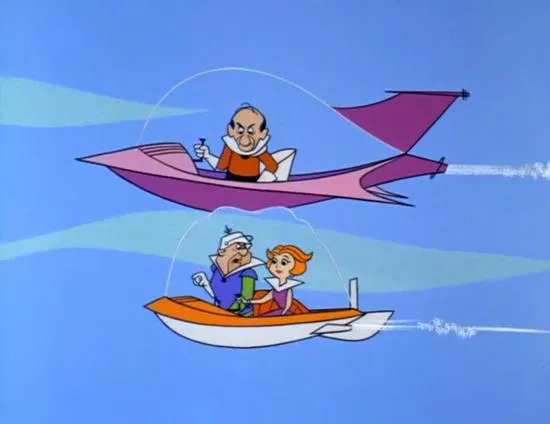

The 18th episode of “The Jetsons” originally aired on January 27, 1963, and was titled “Jane’s Driving Lesson.” As one might expect with a title like that, the episode deals with the flying cars of the year 2063. Specifically, female drivers of the year 2063.

This episode wears its sexism rather proudly at every turn, playing it for laughs as men are constantly terrified of women behind the wheel — or the yoke as the case may be. George pulls up behind a young woman driver and becomes confused by her hand signals. “Women drivers, that’s the problem!” George shouts at the woman.

When we looked at the 15th episode of “The Jetsons,” titled “Millionaire Astro,” I wrote about the social and economic conservatism of the show. This episode is another example of the show’s conservatism, again not in the “red state versus blue state” political sense, but rather in its affirmation of the social status quo. But where did this myth that women are worse drivers than men come from?

Michael L. Berger writes in his 1986 paper “Women Drivers!: The Emergence of Folklore and Stereotypic Opinions Concerning Feminine Automotive Behavior” about the history of the stereotype that women are poor drivers. Much like in the way that the “women are bad drivers” jokes are presented in “The Jetsons,” there is a long history of using humor to perpetuate this sexist rhetoric:

For although often presented in a humorous context, folklore concerning women drivers, and the accompanying negative stereotype emerged for very serious social reasons. They were attempts to both keep women in their place and to protect them against corrupting influences in society, and within themselves.

As Berger points out in his paper, the idea that women were bad drivers was very much rooted in class and wealth. However, the stereotype didn’t really gain traction until the 1920s, when middle class American women started to have access to automobiles. Up until that point it was only a wealthy handful (whether male or female) who could afford such a luxury like a car:

As long as motoring was limited to wealthy urban women, there was little criticism of their ability as drivers. These were women of high social and economic station, who made a vocation of leisure-time pursuits. If they chose to spend their time motoring around the city rather than at home giving teas few would criticize. Such changes posed little or no threat to the established social order, and hence there was no need for a negative stereotype.

In the 1910s prices of cars were coming down and many men were going off to fight the first World War, leaving women with both the “need and opportunity” to learn how to drive for those who hadn’t already:

By the end of , there existed the real possibility that the automobile could be adopted by large numbers of middle-class women. It is from this period, and not that of the initial introduction of the motor car, that we can trace the origins of the women driver stereotype and the folklore of which it is a part.

Jane Jetson was very much the American middle-class everywoman of 2063 — the woman that women of 1963 were supposed to identify with on the show, and in turn the woman that girls of 1963 were supposed to see as their future.

Jane receives a driving lesson during the episode but when the instructor wants to stop off to check his safe deposit box (and his life insurance policy) a bank robber emerges and jumps in. Jane continues on driving, believing that he must be just another driving instructor. The bank robber is terrified of Jane’s driving and by the end of the episode he’s begging to be put in jail rather than endure more time in the flying car with Jane.

After George finds Jane at the police stations the status quo is restored (George is again behind the yoke) and Jane explains, “You know George, I don’t really care much about driving anyway.”

George responds, “Well, it’s probably better if you don’t Janey. Driving requires a man’s skill; a man’s judgement; a man’s technical know-how.”

“And what about a man’s eyesight, George?” Jane replies just before George realizes he went through a red light and crashes into a parked car. This, like so many of these “women are bad at stuff” tropes from midcentury sitcoms, is meant to be the kicker. The audience is given a sly wink — isn’t it ridiculous that a man could be just a terrible as a woman behind the wheel?

Thanks to an unsympathetic judge (the parked car George plowed into was owned by the judge) George has to start taking the flying bus. Interestingly, the only other time in the series that we see a bus stop (other than early in this episode) is in the first episode, when Rosey tries to sullenly run away.

Much like other episodes of “The Jetsons,” we’re left to wonder what kind of real-world impact a different depiction of the future may have had on the world we live in today. Obviously, the episode is little more than one long “women are terrible drivers” joke and it’s easy to dismiss it as such, but it was seen repeatedly throughout the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s by kids all over the world. Time and again we see “The Jetsons” used as a way to talk about the future in which we’re currently living.

Today men like Tim Cook, the CEO of Apple, point to products like the iPhone and say “we’re living The Jetsons with this.” What if the Jetsons points of reference people use in the 21st century weren’t just technological? What if someone could point to other forms of progress and say, “This is the Jetsons. We’re truly living in the future with this.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)