John Brown’s Day of Reckoning

The abolitionist’s bloody raid on a federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry 150 years ago set the stage for the Civil War

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/John-Brown-raid-Harpers-Ferry-631.jpg)

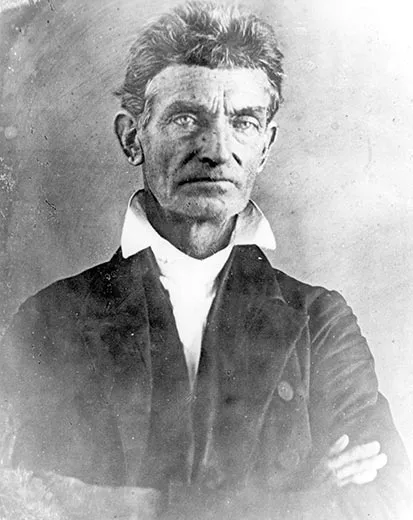

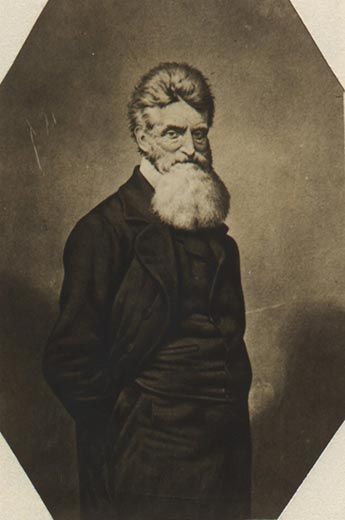

Harpers Ferry, Virginia, lay sleeping on the night of October 16, 1859, as 19 heavily armed men stole down mist-shrouded bluffs along the Potomac River where it joins the Shenandoah. Their leader was a rail-thin 59-year-old man with a shock of graying hair and penetrating steel-gray eyes. His name was John Brown. Some of those who strode across a covered railway bridge from Maryland into Virginia were callow farm boys; others were seasoned veterans of the guerrilla war in disputed Kansas. Among them were Brown's youngest sons, Watson and Oliver; a fugitive slave from Charleston, South Carolina; an African-American student at Oberlin College; a pair of Quaker brothers from Iowa who had abandoned their pacifist beliefs to follow Brown; a former slave from Virginia; and men from Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania and Indiana. They had come to Harpers Ferry to make war on slavery.

The raid that Sunday night would be the most daring instance on record of white men entering a Southern state to incite a slave rebellion. In military terms, it was barely a skirmish, but the incident electrified the nation. It also created, in John Brown, a figure who after a century and a half remains one of the most emotive touchstones of our racial history, lionized by some Americans and loathed by others: few are indifferent. Brown's mantle has been claimed by figures as diverse as Malcolm X, Timothy McVeigh, Socialist leader Eugene Debs and abortion protesters espousing violence. "Americans do not deliberate about John Brown—they feel him," says Dennis Frye, the National Park Service's chief historian at Harpers Ferry. "He is still alive today in the American soul. He represents something for each of us, but none of us is in agreement about what he means."

"The impact of Harpers Ferry quite literally transformed the nation," says Harvard historian John Stauffer, author of The Black Hearts of Men: Radical Abolitionists and the Transformation of Race. The tide of anger that flowed from Harpers Ferry traumatized Americans of all persuasions, terrorizing Southerners with the fear of massive slave rebellions, and radicalizing countless Northerners, who had hoped that violent confrontation over slavery could be indefinitely postponed. Before Harpers Ferry, leading politicians believed that the widening division between North and South would eventually yield to compromise. After it, the chasm appeared unbridgeable. Harpers Ferry splintered the Democratic Party, scrambled the leadership of the Republicans and produced the conditions that enabled Republican Abraham Lincoln to defeat two Democrats and a third-party candidate in the presidential election of 1860.

"Had John Brown's raid not occurred, it is very possible that the 1860 election would have been a regular two-party contest between antislavery Republicans and pro-slavery Democrats," says City University of New York historian David Reynolds, author of John Brown: Abolitionist. "The Democrats would probably have won, since Lincoln received just 40 percent of the popular vote, around one million votes less than his three opponents." While the Democrats split over slavery, Republican candidates such as William Seward were tarnished by their association with abolitionists; Lincoln, at the time, was regarded as one of his party's more conservative options. "John Brown was, in effect, a hammer that shattered Lincoln's opponents into fragments," says Reynolds. "Because Brown helped to disrupt the party system, Lincoln was carried to victory, which in turn led 11 states to secede from the Union. This in turn led to the Civil War."

Well into the 20th century, it was common to dismiss Brown as an irrational fanatic, or worse. In the rousing pro-Southern 1940 classic film Santa Fe Trail, actor Raymond Massey portrayed him as a wild-eyed madman. But the civil rights movement and a more thoughtful acknowledgment of the nation's racial problems have occasioned a more nuanced view. "Brown was thought mad because he crossed the line of permissible dissent," Stauffer says. "He was willing to sacrifice his life for the cause of blacks, and for this, in a culture that was simply marinated in racism, he was called mad."

Brown was a hard man, to be sure, "built for times of trouble and fitted to grapple with the flintiest hardships," in the words of his close friend, the African-American orator Frederick Douglass. Brown felt a profound and lifelong empathy with the plight of slaves. "He stood apart from every other white in the historical record in his ability to burst free from the power of racism," says Stauffer. "Blacks were among his closest friends, and in some respects he felt more comfortable around blacks than he did around whites."

Brown was born with the century, in 1800, in Connecticut, and raised by loving if strict parents who believed (as did many, if not most, in that era) that righteous punishment was an instrument of the divine. When he was a small boy, the Browns moved west in an ox-drawn wagon to the raw wilderness of frontier Ohio, settling in the town of Hudson, where they became known as friends to the rapidly diminishing population of Native Americans, and as abolitionists who were always ready to help fugitive slaves. Like many restless 19th-century Americans, Brown tried many professions, failing at some and succeeding modestly at others: farmer, tanner, surveyor, wool merchant. He married twice—his first wife died from illness—and, in all, fathered 20 children, almost half of whom died in infancy; 3 more would die in the war against slavery. Brown, whose beliefs were rooted in strict Calvinism, was convinced that he had been predestined to bring an end to slavery, which he believed with burning certitude was a sin against God. In his youth, both he and his father, Owen Brown, had served as "conductors" on the Underground Railroad. He had denounced racism within his own church, where African-Americans were required to sit in the back, and shocked neighbors by dining with blacks and addressing them as "Mr." and "Mrs." Douglass once described Brown as a man who "though a white gentleman, is in sympathy, a black man, and as deeply interested in our cause, as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery."

In 1848, the wealthy abolitionist Gerrit Smith encouraged Brown and his family to live on land Smith had bestowed on black settlers in northern New York. Tucked away in the Adirondack Mountains, Brown concocted a plan to liberate slaves in numbers never before attempted: A "Subterranean Pass-Way"—the Underground Railroad writ large—would stretch south through the Allegheny and Appalachian mountains, linked by a chain of forts manned by armed abolitionists and free blacks. "These warriors would raid plantations and run fugitives north to Canada," says Stauffer. "The goal was to destroy the value of slave property." This scheme would form the template for the Harpers Ferry raid and, says Frye, under different circumstances "could have succeeded. [Brown] knew that he couldn't free four million people. But he understood economics and how much money was invested in slaves. There would be a panic—property values would dive. The slave economy would collapse."

Political events of the 1850s turned Brown from a fierce, if essentially garden-variety, abolitionist into a man willing to take up arms, even die, for his cause. The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which imposed draconian penalties on anyone caught helping a runaway and required all citizens to cooperate in the capture of fugitive slaves, enraged Brown and other abolitionists. In 1854, another act of Congress pushed still more Northerners beyond their limits of tolerance. Under pressure from the South and its Democratic allies in the North, Congress opened the territories of Kansas and Nebraska to slavery under a concept called "popular sovereignty." The more northerly Nebraska was in little danger of becoming a slave state. Kansas, however, was up for grabs. Pro-slavery advocates—"the meanest and most desperate of men, armed to the teeth with Revolvers, Bowie Knives, Rifles & Cannon, while they are not only thoroughly organized, but under pay from Slaveholders," John Brown Jr. wrote to his father—poured into Kansas from Missouri. Antislavery settlers begged for guns and reinforcements. Among the thousands of abolitionists who left their farms, workshops or schools to respond to the call were John Brown and five of his sons. Brown himself arrived in Kansas in October 1855, driving a wagon loaded with rifles he had picked up in Ohio and Illinois, determined, he said, "to help defeat Satan and his legions."

In May 1856, pro-slavery raiders sacked Lawrence, Kansas, in an orgy of burning and looting. Almost simultaneously, Brown learned that Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, the most outspoken abolitionist in the U.S. Senate, had been beaten senseless on the floor of the chamber by a cane-wielding congressman from South Carolina. Brown raged at the North's apparent helplessness. Advised to act with restraint, he retorted, "Caution, caution, sir. I am eternally tired of hearing the word caution. It is nothing but the word of cowardice." A party of Free-Staters led by Brown dragged five pro-slavery men out of their isolated cabins on eastern Kansas' Pottawatomie Creek and hacked them to death with cutlasses. The horrific nature of the murders disturbed even abolitionists. Brown was unrepentant. "God is my judge," he laconically replied when asked to account for his actions. Though he was a wanted man who hid out for a time, Brown eluded capture in the anarchic conditions that pervaded Kansas. Indeed, almost no one—pro-slavery or antislavery—was ever arraigned in a court for killings that took place during the guerrilla war there.

The murders, however, ignited reprisals. Pro-slavery "border ruffians" raided Free- Staters' homesteads. Abolitionists fought back. Hamlets were burned, farms abandoned. Brown's son Frederick, who had participated in the Pottawatomie Creek massacre, was shot dead by a pro-slavery man. Although Brown survived many brushes with opponents, he seemed to sense his own fate. In August 1856 he told his son Jason, "I have only a short time to live—only one death to die, and I will die fighting for this cause."

By almost any definition, the Pottawatomie killings were a terrorist act, intended to sow fear in slavery's defenders. "Brown viewed slavery as a state of war against blacks—a system of torture, rape, oppression and murder—and saw himself as a soldier in the army of the Lord against slavery," says Reynolds. "Kansas was Brown's trial by fire, his initiation into violence, his preparation for real war," he says. "By 1859, when he raided Harpers Ferry, Brown was ready, in his own words, ‘to take the war into Africa'—that is, into the South."

In January 1858, Brown left Kansas to seek support for his planned Southern invasion. In April, he sought out a diminutive former slave, Harriet Tubman, who had made eight secret trips to Maryland's Eastern Shore to lead dozens of slaves north to freedom. Brown was so impressed that he began referring to her as "General Tubman." For her part, she embraced Brown as one of the few whites she had ever met who shared her belief that antislavery work was a life-and-death struggle. "Tubman thought Brown was the greatest white man who ever lived," says Kate Clifford Larson, author of Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero.

Having secured financial backing from wealthy abolitionists known as the "Secret Six," Brown returned to Kansas in mid-1858. In December, he led 12 fugitive slaves on an epic journey eastward, dodging pro-slavery guerrillas and marshals' posses and fighting and defeating a force of United States troops. Upon reaching Detroit, they were ferried across the Detroit River to Canada. Brown had covered nearly 1,500 miles in 82 days, proof to doubters, he felt sure, that he was capable of making the Subterranean Pass-Way a reality.

With his "Secret Six" war chest, Brown purchased hundreds of Sharps carbines and thousands of pikes, with which he planned to arm the first wave of slaves he expected to flock to his banner once he occupied Harpers Ferry. Many thousands more could then be armed with rifles stored at the federal arsenal there. "When I strike, the bees will swarm," Brown assured Frederick Douglass, whom he urged to sign on as president of a "Provisional Government." Brown also expected Tubman to help him recruit young men for his revolutionary army, and, says Larson, "to help infiltrate the countryside before the raid, encourage local blacks to join Brown and when the time came, to be at his side—like a soldier." Ultimately, neither Tubman nor Douglass participated in the raid. Douglass was sure the venture would fail. He warned Brown that he was "going into a perfect steel trap, and that he would not get out alive." Tubman may have concluded that if Brown's plan failed, the Underground Railroad would be destroyed, its routes, methods and participants exposed.

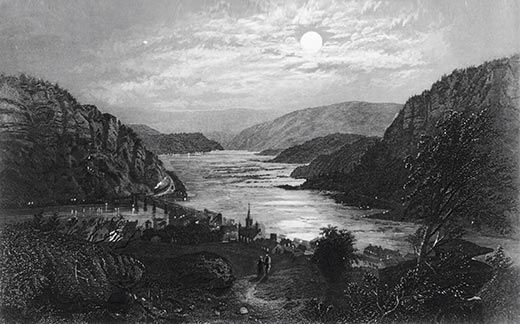

Sixty-one miles northwest of Washington, D.C., at the junction of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, Harpers Ferry was the site of a major federal armory, including a musket factory and rifle works, an arsenal, several large mills and an important railroad junction. "It was one of the most heavily industrialized towns south of the Mason-Dixon line," says Frye. "It was also a cosmopolitan town, with a lot of Irish and German immigrants, and even Yankees who worked in the industrial facilities." The town and its environs' population of 3,000 included about 300 African-Americans, evenly divided between slave and free. But more than 18,000 slaves—the "bees" Brown expected to swarm—lived in the surrounding counties.

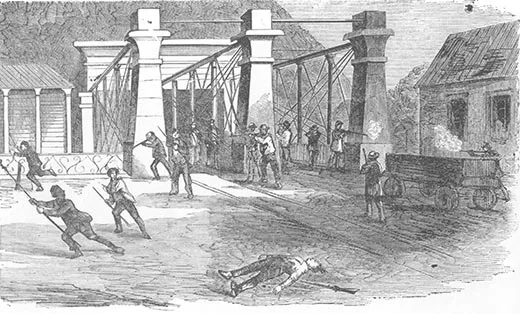

As his men stepped off the railway bridge into town that October night in 1859, Brown dispatched contingents to seize the musket factory, rifle works, arsenal and adjacent brick fire-engine house. (Three men remained in Maryland to guard weapons that Brown hoped to distribute to slaves who joined him.) "I want to free all the negroes in this state," he told one of his first hostages, a night watchman. "If the citizens interfere with me, I must only burn the town and have blood." Guards were posted at the bridges. Telegraph lines were cut. The railroad station was seized. It was there that the raid's first casualty occurred, when a porter, a free black man named Hayward Shepherd, challenged Brown's men and was shot dead in the dark. Once key locations had been secured, Brown sent a detachment to seize several prominent local slave owners, including Col. Lewis W. Washington, a great-grandnephew of the first president.

Early reports claimed that Harpers Ferry had been taken by 50, then 150, then 200 white "insurrectionists" and "six hundred runaway negroes." Brown expected to have 1,500 men under his command by midday Monday. He later said he believed that he would eventually have armed as many as 5,000 slaves. But the bees did not swarm. (Only a handful of slaves lent Brown assistance.) Instead, as Brown's band watched dawn break over the craggy ridges enclosing Harpers Ferry, local white militias—similar to today's National Guard—were hastening to arms.

First to arrive were the Jefferson Guards, from nearby Charles Town. Uniformed in blue, with tall black Mexican War-era shakos on their heads and brandishing .58-caliber rifles, they seized the railway bridge, killing a former slave named Dangerfield Newby and cutting Brown off from his route of escape. Newby had gone north in a failed attempt to earn enough money to buy freedom for his wife and six children. In his pocket was a letter from his wife: "It is said Master is in want of money," she had written. "I know not what time he may sell me, and then all my bright hopes of the future are blasted, for their [sic] has been one bright hope to cheer me in all my troubles, that is to be with you."

As the day progressed, armed units poured in from Frederick, Maryland; Martinsburg and Shepherdstown, Virginia; and elsewhere. Brown and his raiders were soon surrounded. He and a dozen of his men held out in the engine house, a small but formidable brick building, with stout oak doors in front. Other small groups remained holed up in the musket factory and rifle works. Acknowledging their increasingly dire predicament, Brown sent out New Yorker William Thompson, bearing a white flag, to propose a cease-fire. But Thompson was captured and held in the Galt House, a local hotel. Brown then dispatched his son, Watson, 24, and ex-cavalryman Aaron Stevens, also under a white flag, but the militiamen shot them down in the street. Watson, although fatally wounded, managed to crawl back to the engine house. Stevens, shot four times, was arrested.

When the militia stormed the rifle works, the three men inside dashed for the shallow Shenandoah, hoping to wade across. Two of them—John Kagi, vice president of Brown's provisional government, and Lewis Leary, an African-American—were shot dead in the water. The black Oberlin student, John Copeland, reached a rock in the middle of the river, where he threw down his gun and surrendered. Twenty-year-old William Leeman slipped out of the engine house, hoping to make contact with the three men Brown had left as backup in Maryland. Leeman plunged into the Potomac and swam for his life. Trapped on an islet, he was shot dead as he tried to surrender. Throughout the afternoon, bystanders took potshots at his body.

Through loopholes—small openings through which guns could be fired—that they had drilled in the engine house's thick doors, Brown's men tried to pick off their attackers, without much success. One of their shots, however, killed the town's mayor, Fontaine Beckham, enraging the local citizenry. "The anger at that moment was uncontrollable," says Frye. "A tornado of rage swept over them." A vengeful mob pushed its way into the Galt House, where William Thompson was being held prisoner. They dragged him onto the railroad trestle, shot him in the head as he begged for his life and tossed him over the railing into the Potomac.

By nightfall, conditions inside the engine house had grown desperate. Brown's men had not eaten for more than 24 hours. Only four remained unwounded. The bloody corpses of slain raiders, including Brown's 20-year-old son, Oliver, lay at their feet. They knew there was no hope of escape. Eleven white hostages and two or three of their slaves were pressed against the back wall, utterly terrified. Two pumpers and hose carts were pushed against the doors, to brace against an assault expected at any moment. Yet if Brown felt defeated, he didn't show it. As his son Watson writhed in agony, Brown told him to die "as becomes a man."

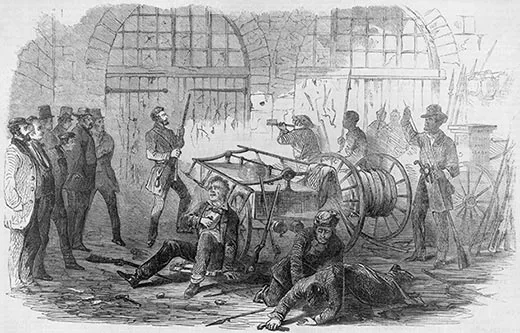

Soon perhaps a thousand men—many uniformed and disciplined, others drunk and brandishing weapons from shotguns to old muskets—would fill the narrow lanes of Harpers Ferry, surrounding Brown's tiny band. President James Buchanan had dispatched a company of Marines from Washington, under the command of one of the Army's most promising officers: Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee. Himself a slave owner, Lee had only disdain for abolitionists, who "he believed were exacerbating tensions by agitating among slaves and angering masters," says Elizabeth Brown Pryor, author of Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters. "He held that although slavery was regrettable, it was an institution sanctioned by God and as such would disappear only when God ordained it." Dressed in civilian clothes, Lee reached Harpers Ferry around midnight. He gathered the 90 Marines behind a nearby warehouse and worked out a plan of attack. In the predawn darkness, Lee's aide, a flamboyant young cavalry lieutenant, boldly approached the engine house, carrying a white flag. He was met at the door by Brown, who asked that he and his men be allowed to retreat across the river to Maryland, where they would free their hostages. The soldier promised only that the raiders would be protected from the mob and put on trial. "Well, lieutenant, I see we can't agree," replied Brown. The lieutenant stepped aside, and with his hand gave a prearranged signal to attack. Brown could have shot him dead—"just as easily as I could kill a musquito," he recalled later. Had he done so, the course of the Civil War might have been different. The lieutenant was J.E.B. Stuart, who would go on to serve brilliantly as Lee's cavalry commander.

Lee first sent several men crawling below the loopholes, to smash the door with sledgehammers. When that failed, a larger party charged the weakened door, using a ladder as a battering ram, punching through on their second try. Lt. Israel Green squirmed through the hole to find himself beneath one of the pumpers. According to Frye, as Green emerged into the darkened room, one of the hostages pointed at Brown. The abolitionist turned just as Green lunged forward with his saber, striking Brown in the gut with what should have been a death blow. Brown fell, stunned but astonishingly unharmed: the sword had struck a buckle and bent itself double. With the sword's hilt, Green then hammered Brown's skull until he passed out. Although severely injured, Brown would survive. "History may be a matter of a quarter of an inch," says Frye. "If the blade had struck a quarter inch to the left or right, up or down, Brown would have been a corpse, and there would have been no story for him to tell, and there would have been no martyr."

Meanwhile, the Marines poured through the breach. Brown's men were overwhelmed. One Marine impaled Indianan Jeremiah Anderson against a wall. Another bayoneted young Dauphin Thompson, where he lay under a fire engine. It was over in less than three minutes. Of the 19 men who strode into Harpers Ferry less than 36 hours before, five were now prisoners; ten had been killed or fatally injured. Four townspeople had also died; more than a dozen militiamen were wounded.

Only two of Brown's men escaped the siege. Amid the commotion, Osborne Anderson and Albert Hazlett slipped out the back of the armory, climbed a wall and scuttled behind the embankment of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to the bank of the Potomac, where they found a boat and paddled to the Maryland shore. Hazlett and another of the men whom Brown had left behind to guard supplies were later captured in Pennsylvania and extradited to Virginia. Of the total, five members of the raiding party would eventually make their way to safety in the North or Canada.

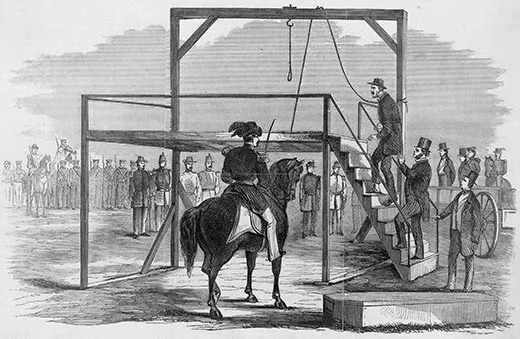

Brown and his captured men were charged with treason, first-degree murder and "conspiring with Negroes to produce insurrection." All of the charges carried the death penalty. The trial, held in Charles Town, Virginia, began on October 26; the verdict was guilty, and Brown was sentenced on November 2. Brown met his death stoically on the morning of December 2, 1859. He was led out of the Charles Town jail, where he had been held since his capture, and seated on a small wagon carrying a white pine coffin. He handed a note to one of his guards: "I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land: will never be purged away; but with blood." Escorted by six companies of infantry, he was transported to a scaffold where, at 11:15, a sack was placed over his head and a rope fitted around his neck. Brown told his guard, "Don't keep me waiting longer than necessary. Be quick." These were his last words. Among the witnesses to his death were Robert E. Lee and two other men whose lives would be irrevocably changed by the events at Harpers Ferry. One was a Presbyterian professor from the Virginia Military Institute, Thomas J. Jackson, who would earn the nickname "Stonewall" less than two years later at the Battle of Bull Run. The other was a young actor with seductive eyes and curly hair, already a fanatical believer in Southern nationalism: John Wilkes Booth. The remaining convicted raiders would be hanged, one by one.

Brown's death stirred blood in the North and the South for opposing reasons. "We shall be a thousand times more Anti-Slavery than we ever dared to think of being before," proclaimed the Newburyport (Massachusetts) Herald. "Some eighteen hundred years ago Christ was crucified," Henry David Thoreau opined in a speech in Concord on the day of Brown's execution, "This morning, perchance, Captain Brown was hung. These are the two ends of a chain which is not without its links. He is not Old Brown any longer; he is an angel of light." In 1861, Yankee soldiers would march to battle singing: "John Brown's body lies a-mouldering in the grave, but his soul goes marching on."

On the other side of the Mason-Dixon line, "this was the South's Pearl Harbor, its ground zero," says Frye. "There was a heightened sense of paranoia, a fear of more abolitionist attacks—that more Browns were coming any day, at any moment. The South's greatest fear was slave insurrection. They all knew that if you held four million people in bondage, you're vulnerable to attack." Militias sprang up across the South. In town after town, units organized, armed and drilled. When war broke out in 1861, they would provide the Confederacy with tens of thousands of well-trained soldiers. "In effect, 18 months before Fort Sumter, the South was already declaring war against the North," says Frye. "Brown gave them the unifying momentum they needed, a common cause based on preserving the chains of slavery."

Fergus M. Bordewich, a frequent contributor of articles on history, is profiled in the "From the Editor" column.