John Muir’s Yosemite

The father of the conservation movement found his calling on a visit to the California wilderness

The naturalist John Muir is so closely associated with Yosemite National Park—after all, he helped draw up its proposed boundaries in 1889, wrote the magazine articles that led to its creation in 1890 and co-founded the Sierra Club in 1892 to protect it—that you'd think his first shelter there would be well marked. But only park historians and a few Muir devotees even know where the little log cabin was, just yards from the Yosemite Falls Trail. Maybe that's not such a bad thing, for here one can experience the Yosemite that inspired Muir. The crisp summer morning that I was guided to the site, the mountain air was perfumed with ponderosa and cedar; jays, larks and ground squirrels gamboled about. And every turn offered picture-postcard views of the valley's soaring granite cliffs, so majestic that early visitors compared them to the walls of Gothic cathedrals. No wonder many 19th-century travelers who visited Yosemite saw it as a new Eden.

Leading me through the forest was Bonnie Gisel, curator of the Sierra Club's LeConte Memorial Lodge and the author of several books on Muir. "Yosemite Valley was the ultimate pilgrimage site for Victorian Americans," Gisel said. "Here was the absolute manifestation of the divine, where they could celebrate God in nature." We were in a cool, shady grotto filled with bracken fern and milkweed, as picturesque a place as fans of the drifter who would become America's most influential conservationist might wish. Although no structure remains, we know from Muir's diaries and letters that he built the one-room cabin from pine and cedar with his friend Harry Randall, and that he diverted nearby Yosemite Creek to run beneath its floor. "Muir loved the sound of water," Gisel explained. Plants grew through the floorboards; he wove the threads of two ferns into what he called an "ornamental arch" over his writing desk. And he slept on sheepskin blankets over cedar branches. "Muir wrote about frogs chirping under the floors as he slept," Gisel said. "It was like living in a greenhouse."

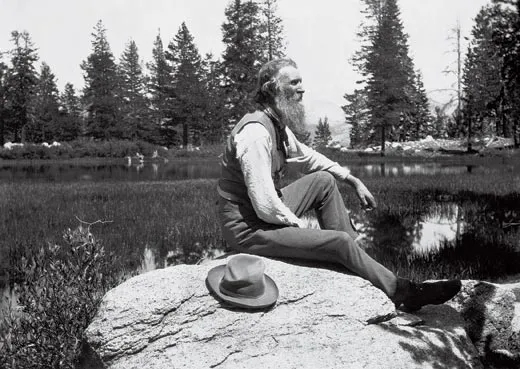

Today, Muir has become such an icon that it's hard to remember that he was ever a living human being, let alone a wide-eyed and adventurous young man—a Gilded Age flower child. Even at the Yosemite Visitor Center, he's depicted in a life-size bronze statue as a wizened prophet with a Methuselah beard. In a nearby museum, his battered tin cup and the traced outline of his foot are displayed like religious relics. And his pithy inspirational quotes—"Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature's peace will flow into you as sunshine into trees"—are everywhere. But all this hero worship risks obscuring the real story of the man and his achievements.

"There are an amazing number of misconceptions about John Muir," says Scott Gediman, the park's public affairs officer. "People think he discovered Yosemite or started the national park system. Others assume he lived here all his life." In fact, says Gediman, Muir lived in Yosemite off and on for only a short but intense period from 1868 to 1874, an experience that transformed him into a successor to Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Later in life, Muir would return to Yosemite on shorter trips, burdened with his own celebrity and the responsibilities of family and work. But it was during the happy period of his relative youth, when he was free to amble around Yosemite, that Muir's ideas were shaped. Some of his most famous adventures, recounted in his books The Yosemite and Our National Parks, were from this time.

"As a young man, Muir felt he was a student in what he called the ‘University of the Wilderness,'" Gisel said. "Yosemite was his graduate course. This is where he decided who he was, what he wanted to say and how he was going to say it."

When he first strode into Yosemite in the spring of 1868, Muir was a scruffy Midwestern vagabond wandering the wilderness fringes of post-bellum America, taking odd jobs where he could. In retrospect, visiting Yosemite might seem an inevitable stop on his life's journey. But his later recollections reveal a young man plagued with self-doubt and uncertainty, often lonely and confused about the future. "I was tormented with soul hunger," he wrote of his meandering youth. "I was on the world. But was I in it?"

John Muir was born in Dunbar, Scotland, in 1838, the eldest son of a Calvinist shopkeeper father. When John was 11, the family immigrated to the United States, to homestead near Portage, Wisconsin. Though his days were consumed with farm work, he was a voracious reader. By his mid-20s, Muir seemed to have a career as an inventor ahead of him. His gadgets included an "early-rising bed," which raised the sleeper to an upright position, and a clock made in the shape of a scythe, to signify the advance of Father Time. But after being nearly blinded in a factory mishap in 1867, Muir decided to devote his life to studying the beauties of Creation. With almost no money and already sporting the full beard that would become his trademark, he set off on a 1,000-mile walk from Kentucky to Florida, intending to continue to South America to see the Amazon. But a bout of malaria in Florida's Cedar Key forced a change in plans. He sailed to San Francisco via Panama, intending to stay only a short time.

Muir would later famously, and perhaps apocryphally, recall that after hopping off the boat in San Francisco on March 28, 1868, he asked a carpenter on the street the quickest way out of the chaotic city. "Where do you want to go?" the carpenter replied, and Muir responded, "Anywhere that is wild." Muir started walking east.

This glorious landscape had an ignoble history. The first white visitors were vigilantes from the so-called Mariposa Battalion, who were paid by the California government to stop Indian raids on trading posts. They rode into Yosemite in 1851 and 1852 in pursuit of the Ahwahneechee, a branch of the southern Miwok. Some Indians were killed and their village was burned. The survivors were driven from the valley and returned later only in small, heartbroken bands. The vigilantes brought back stories of a breathtaking seven-mile-long gorge framed by monumental cliffs, now known as El Capitan and Half Dome, and filled with serene meadows and spectacular waterfalls.

The first tourists began arriving in Yosemite a few years later, and by the early 1860s, a steady trickle of them, most from San Francisco, 200 miles away, was turning up in summer. Traveling for several days by train, stagecoach and horseback, they would reach Mariposa Grove, a stand of some 200 ancient giant sequoias, where they would rest before embarking on an arduous descent via 26 switchbacks into the valley. Once there, many did not stray far from the few rustic inns, but others would camp out in the forests, eating oatcakes and drinking tea, hiking to mountain vistas such as Glacier Point, reading poetry around campfires and yodeling across moonlit lakes. By 1864, a group of Californians, aware of what had happened to Niagara Falls, successfully lobbied President Abraham Lincoln to sign a law granting the roughly seven square miles of the valley and Mariposa Grove to the state "for public use, resort and recreation"—some of the first land in history set aside for its natural beauty.

Thus, when Muir came to Yosemite in 1868, he found several dozen year-round residents living in the valley—even an apple orchard. Because of a gap in his journals, we know little about that first visit except that it lasted about ten days. He returned to the coast to find work, promising himself to return.

It would take him over a year to do so. In June 1869, Muir signed on as a shepherd to take a flock of 2,000 sheep to Tuolumne Meadows in the High Sierra, an adventure he later recounted in one of his most appealing books, My First Summer in the Sierra. Muir came to despise his "hoofed locusts" for tearing up the grass and devouring wildflowers. But he discovered a dazzling new world. He made dozens of forays into the mountains, including the first ascent of the 10,911-foot granite spire of Cathedral Peak, with nothing but a notebook tied to his rope belt and lumps of hard bread in his coat pockets. By fall 1869, Muir had decided to stay full time in the valley, which he regarded as "nature's landscape garden, at once beautiful and sublime." He built and ran a sawmill for James Hutchings, proprietor of the Hutchings House hotel, and, in November 1869, constructed his fern-filled cabin by Yosemite Creek. Muir lived there for 11 months, guiding hotel guests on hikes and cutting timber for walls to replace bedsheets hung as "guest room" partitions. Muir's letters and journals find him spending hour after hour simply marveling at the beauty around him. "I am feasting in the Lord's mountain house," he wrote his lifelong Wisconsin friend and mentor Jeanne Carr, "and what pen may write my blessings?" But he missed his family and friends. "I find no human sympathy," he wrote at one low ebb, "and I hunger."

We have a vivid picture of Muir at this time thanks to Theresa Yelverton, a.k.a. Viscountess Avonmore, a British writer who arrived in Yosemite as a 33-year-old tourist in the spring of 1870. Carr had told her to seek out Muir as a guide and the pair became friends. She recorded her first impressions of him in the novel Zanita: A Tale of the Yo-Semite, a thinly veiled memoir in which Muir is called Kenmuir. He was dressed, she wrote, in "tattered trousers, the waist eked out with a grass band" and held up by "hay-rope suspenders," with "a long flowering sedge rush stuck in the solitary button-hole of his shirt, the sleeves of which were ragged and forlorn." But Yelverton also noted his "bright, intelligent face...and his open blue eyes of honest questioning," which she felt "might have stood as a portrait of the angel Raphael." On their many rambles, she came also to marvel at Muir's energy and charisma: muscular and agile, with a "joyous, ringing laugh," he leapt from boulder to boulder like a mountain goat, rhapsodizing about the wonders of God.

"These are the Lord's fountains," Kenmuir pronounces before one waterfall. "These are the reservoirs whence He pours his floods to cheer the earth, to refresh man and beast, to lave every sedge and tiny moss." When a storm sends trees thundering to the earth around them, Kenmuir is driven to ecstasy: "O, this is grand! This is magnificent! Listen to the voice of the Lord; how he speaks in the sublimity of his power and glory!" The other settlers, she writes, regarded him as slightly mad—"a born fool" who "loafs around this here valley gatherin' stocks and stones."

Muir left Yosemite abruptly in late 1870; some scholars suspect he was fleeing the romantic interest of Lady Yelverton, who had long been separated from a caddish husband. A short time later, in January 1871, Muir returned to Yosemite, where he would spend the next 22 months—his longest stint. On Sunday excursions away from the sawmill, he made detailed studies of the valley's geology, plants and animals, including the water ouzel, or dipper, a songbird that dives into swift streams in search of insects. He camped out on high ledges where he was doused by freezing waterfalls, lowered himself by ropes into "the womb" of a remote glacier and once "rode" an avalanche down a canyon. ("Elijah's flight in a chariot of fire could hardly have been more gloriously exciting," he said of the experience.)

This refreshingly reckless manner, as if he were drunk on nature, is what many fans like to remember about him today. "There has never been a wilderness advocate with the kind of hands-on experience of Muir," says Lee Stetson, editor of an anthology of Muir's outdoor adventure writing and an actor who has portrayed him in one-man shows in Yosemite for the past 25 years. "People tend to think of him as a remote philosopher-king, but there's probably not a single part of this park that he didn't visit himself." Not surprisingly, Native Americans, whom Muir regarded as "dirty," tend to be less enthusiastic about him. "I think Muir has been given entirely too much credit," says Yosemite park ranger Ben Cunningham-Summerfield, a member of the Maidu tribe of Northern California.

In early 1871, Muir had been obliged to leave his idyllic creek-side cabin, which Hutchings wanted to use for his relatives. With his usual inventiveness, Muir built a small study in the sawmill under a gable reachable only by ladder, which he called his "hang-nest." There, surrounded by the many plant specimens he'd gathered on his rambles, he filled journal after journal with his observations of nature and geology, sometimes writing with sequoia sap for added effect. Thanks to Jeanne Carr, who had moved to Oakland and hobnobbed with California's literati, Muir was beginning to develop a reputation as a self-taught genius. The noted scientist Joseph LeConte was so impressed with one of his theories—that the Yosemite Valley had been formed by glacial activity rather than a prehistoric cataclysm, as was widely, and incorrectly, thought—that he encouraged Muir to publish his first article, which appeared in the New York Tribune in late 1871. Ralph Waldo Emerson, by then elderly, spent days with Muir peppering him with botanical questions. (The pair went to Mariposa Grove, but much to Muir's disappointment, Emerson was too frail to camp overnight.)

By the end of 1872, Muir was making occasional appearances in the salons of San Francisco and Oakland, where Carr introduced him as "the wild man of the woods." Writing for outdoor magazines, Muir was able to put his ideas about nature into the vernacular, but he wrestled not only with the act of writing but with the demands of activism. Part of him wanted to simply return to the park and revel in nature. But by the fall of 1874, having visited the valley after a nine-month absence, he concluded that that option was no longer open to him. He had a calling, to protect the wilderness, which required his presence in the wider world. "This chapter of my life is done," he wrote to Carr from Yosemite. "I feel I am a stranger here." Muir, 36, returned to San Francisco.

"Yosemite had been his sanctuary," says Gisel. "The question was now how to protect it. By leaving, he was accepting his new responsibility. He had been a guide for individuals. Now he would be a guide for humanity."

As a celebrated elder statesman of American conservation, he continued to visit Yosemite on a regular basis. In 1889, in his early 50s, Muir camped with Robert Underwood Johnson, an editor of Century magazine, in Tuolumne Meadows, where he had worked as a shepherd in 1869. Together they devised a plan to create a 1,200-square-mile Yosemite National Park, a proposal Congress passed the following year. In 1903, the 65-year-old Muir and President Theodore Roosevelt were able to give Secret Service agents the slip and disappear for three days, camping in the wild. It was during this excursion, historians believe, that Muir persuaded the president to expand the national park system and to combine, under federal authority, both Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove, which had remained under California jurisdiction as authorized by Lincoln decades before. Unification of the park came in 1906.

But just when Muir should have been able to relax, he learned in 1906 that a dam was planned within the park boundaries, in the lovely Hetch Hetchy Valley. Despite a hard fight, he was unable to stop its construction, which Congress authorized in 1913, and he succumbed to pneumonia the next year in 1914, at age 76. But the defeat galvanized the American conservation movement to push for the creation in 1916 of the National Park Service and a higher level of protection for all national parks—a memorial Muir would have relished.

Frequent contributor Tony Perrottet wrote about Europe's house museums for the June 2008 issue of Smithsonian.