John Quincy Adams Kept a Diary and Didn’t Skimp on the Details

On the occasion of his 250th birthday, the making of our sixth president in his own words

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/a5/8ba5ac0e-e554-45de-a7fb-3d37f1cf3091/jqa-npg-portrait-wr.jpeg)

Dazzled by the sights and sounds of Paris in 1778, John Quincy Adams, at the time almost a teenager, dashed off a quick note home. “My Pappa enjoins it upon me to keep a journal, or a diary, of the Events that happen to me, and of objects that I See, and of Characters that I converse with from day, to day,” he wrote to his mother Abigail. The 11-year-old balked at the daily labor of a duty he later called “journalizing,” but John Quincy’s life soon proved colorful enough to set down for history. He survived a Spanish shipwreck and braved Catherine the Great’s Russia. He lived with Benjamin Franklin in France, graduated Harvard in two years, and held key diplomatic posts in Napoleon’s Europe—all before the age of 40.

Adams grew up abroad and came of age with the new country. He was the son of patriots, a polymath, a statesman, and the United States’ sixth president, and plenty of what we know about Adams’s globe-trotting past comes from the rich diary he kept (and still tweets!) in 51 volumes, which are held at the Massachusetts Historical Society and available online.

Here are a few pivotal moments in John Quincy Adams’s diary that made him, well, John Quincy Adams:

Adams’s famous parents had great expectations and good advice.

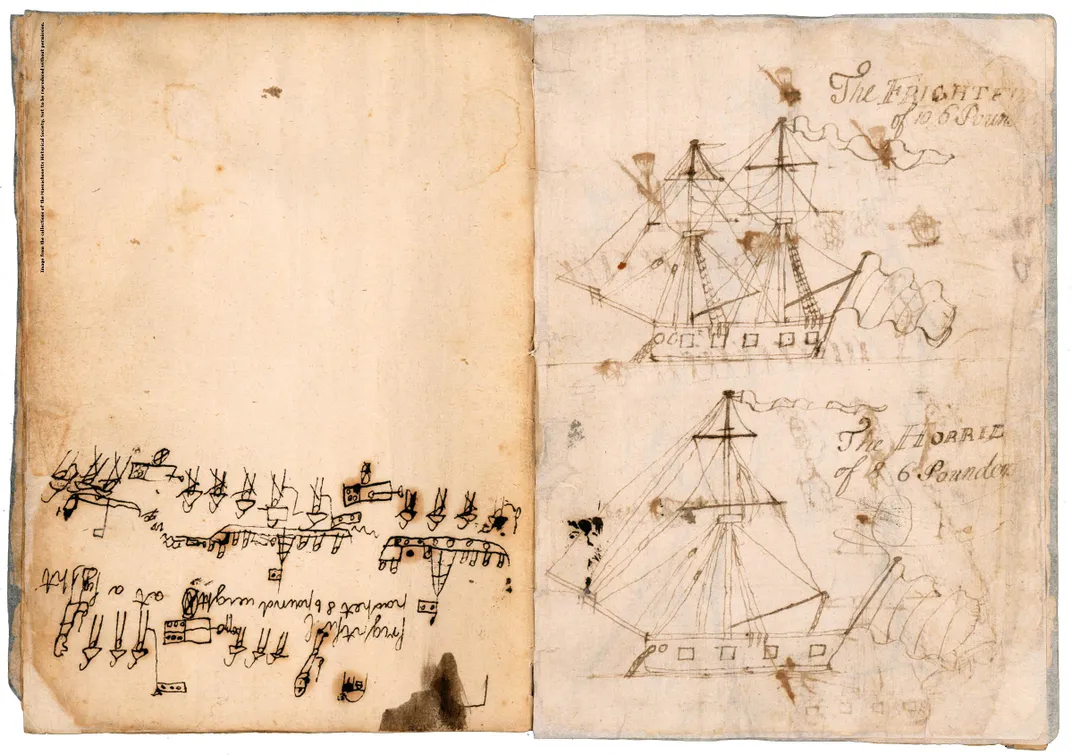

Adams monitored the war’s developments from the homefront in Quincy, Massachusetts, with mother Abigail and siblings Charles, Thomas, and Nabby (a nickname for Abigail). Later, he accompanied his father through Spain, France, England and Holland on diplomatic missions. Here’s the inside back cover of his 1780 diary, where he sketched ships named the Frightful and the Horrid. Young Adams, who later ventured into casual pen-and-ink work, also drew Boston soldiers marching with musket balls and a whimsical mermaid. Thanks to his studies at the Leiden University and an adolescence in Europe, Adams returned to the newly formed United States with a cosmopolitan outlook.

Awarded junior standing, he completed Harvard’s coursework at breakneck pace. From London, where his father was busy opening the first American embassy, Abigail reminded her son that education was a privilege. “If you are conscious to yourself that you possess more knowledge upon some subjects than others of your standing, reflect that you have had greater opportunites of seeing the world, and obtaining a knowledge of Mankind than any of your cotemporarys, that you have never wanted a Book, but it has been supplied you, that your whole time has been spent in the company of Men of Literature and Science,” Abigail wrote, adding: “How unpardonable would it have been in you, to have been a Blockhead.”

At first, Adams wanted to be a poet.

As a young man, John Quincy Adams dabbled in writing verses and odes. His diplomatic career kept him rattling along across continents, with plenty of travel time to hone the craft. “You will never be alone, with a Poet in your Poket. You will never have an idle Hour,” John Quincy heard from his father in 1781. He took the words to heart. He scribbled Romantic verse in his diary on the road, when congressional sessions dragged on, and in moments when he needed solace. Adams never thought he was very good at it.

His fame as a poet shone—briefly—in the twilight of his political years. But he couldn’t put down the pen, as he explained in this melancholy diary entry from October, 16, 1816: “Could I have chosen my own Genius and Condition I should have made myself a great Poet. As it is, I have wasted much of my life in writing verses; spell-bound in the circle of mediocrity.” Later, JQA wrote poems on demand for autograph-seekers.

Adams’s career path cut right through Napoleonic Europe.

By the early 1790s, as a fledging lawyer, John Quincy had turned to the family trade of foreign diplomacy. In this 1794 entry for July 11, his 28th birthday, he records observing President George Washington’s meeting with representatives from the Chickasaw nation. Adams celebrated the day surrounded by paperwork, much as he would for the rest of his professional life. His diary, which operated as catharsis and conscience for the budding statesman, at times sat idle as he pushed through drafting reports.

When he skipped a few days, Adams hustled to catch up the journal “in arrears.” Here, he modestly billed a line or two of big news at the top: his commission to serve as the next U.S. minister to the Netherlands, just as his father had done. So John Quincy looked to the family archive for a “course of reading” that would orient him to the job, digging through “large folio volumes containing dispatches from my father during his negotiations in Europe.” To tackle a thorny diplomatic field like Napoleon’s Europe, Adams made himself a syllabus and stuck to it—an instinct, that, like rereading the family papers for advice, became a lifelong habit.

JQA’s private life was filled with turmoil.

He loved Shakespeare’s tragedies and had strong feelings about quality opera, but Adams’s private life was rife with drama. After a moody courtship (he loathed her favorite books, she mocked his clothes), Adams wed Louisa Catherine Johnson (1775-1852), the sociable daughter of a Maryland merchant based in London. Between a string of diplomatic postings to Prussia, Russia, France and England, they had four children, of whom only Charles Francis Adams outlived his parents. Often, public service called Adams away from home. As a boy, he had fretted over his father’s possible capture and his siblings’ safety. As a husband and parent, John Quincy struggled to teach his children, through distant letters or Bible lessons, in matters of morality. In his diary, he always worried that he hadn’t done enough to protect them—no matter that some of his peers found him cold and grumpy at court. See this warm-hearted bit from his diary for September 6, 1818, as Adams settled into a new job as President James Monroe’s Secretary of State and drafted a formative new doctrine for what became known as the Era of Good Feelings: “Among the desires of my heart, the most deeply anxious is that for the good-conduct and welfare of my children.”

John Quincy Adams’s success came in Congress, not the presidency.

By antebellum political guidelines, Adams seemed like a natural choice for the nation’s highest office in 1824: a seasoned diplomat with founding-era family credentials. As president, he had finalized boundary lines with Canada, stemmed Russian advance into Oregon, established a policy to recognize a roster of new Latin American nations, and acquired Florida. But Adams’ plans for internal improvements, and his wider vision for developing national networks for the arts and sciences, met with little support, as did his bid for reelection.

After a vicious campaign, he was ousted by the Tennessean Andrew Jackson. This stark entry for March 4, 1829 reveals his hurt. Citizens converged for the inauguration festivities but early-riser Adams stayed in, shunning visitors, before taking a solitary ride in the afternoon. Adams, who had taught rhetoric at Harvard and preferred classical orations that nodded to Shakespeare and the Bible, bitterly disliked Jackson’s blunter approach. His successor’s inaugural address, Adams wrote bitingly, “is short, written with some elegance, and remarkable chiefly for a significant threat of Reform.”

On his way home, a fellow rider stopped the former president to ask if he knew who John Quincy Adams was, so that he could deliver papers? Barely a day out of office, Adams likely felt pushed aside to make way for a Jacksonian era bustling with new people, ideas and goods. He dove quickly back into politics, entering Congress to represent Massachusetts in 1831 and served until his death on the job in February 1848. While there, he successfully defeated the gag rule, and persuaded President Martin Van Buren to champion the bequest that brought the Smithsonian to life. If he was exhausted, “Old Man Eloquent” tried hard not to show it. He kept up his daily loop of congressional meetings, signed away fast poems for fans, and stayed up until four o’clock in the morning to compose speeches that he delivered from New York to Ohio.

Adams’s views on slavery and race evolved over the course of his career.

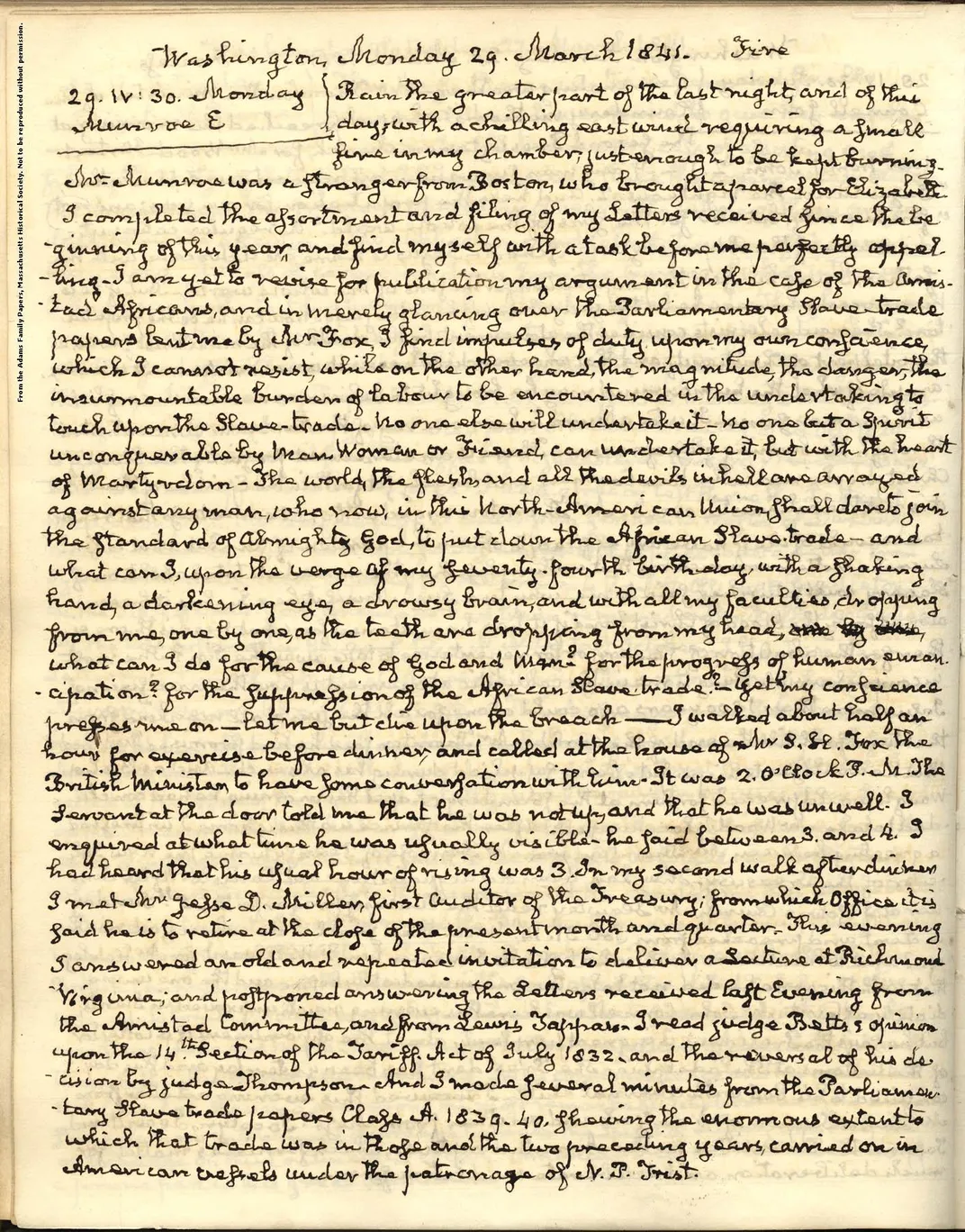

Raised by two fervent antislavery advocates, Adams’ outlook on slavery—and what ending it meant for the American union—took many turns in his diary’s pages. When, in 1841, Adams took up the Amistad case and defended 53 captive Africans, the trial’s physical and spiritual toll was mirrored in his journal. The Amistad case weighed on him, and Adams pushed back. Over two days, he argued for almost nine hours, demanding the Africans’ liberty. His diary, like “a second Conscience,” kept ticking along in the trial’s aftermath. “What can I, upon the verge of my seventy-fourth birthday, with a shaking hand, a darkening eye, a drowsy brain, and with all my faculties, dropping from me, one by one, as the teeth are dropping from my head, what can I do for the cause of God and Man? for the progress of human emancipation? for the suppression of the African Slave-trade?” an elderly Adams wrote in his diary on March 29, 1841. “Yet my conscience presses me on—let me but died upon the breach.”

Want to read a president’s diary? Join the Adams Papers' first-ever transcribe-a-thon on July 15, or get involved in the Massachusetts Historical Society’s newly launched #JQA250 appeal.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/georgini.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/georgini.png)