Representative Joseph Hayne Rainey rose from his intricately carved wooden desk, ready to deliver one of the most important speeches of his life. The campaign for a new civil rights bill had stalled in the Senate, and Rainey could sense support in the House slipping away. White members of Congress had no experience living in fear of the Ku Klux Klan or being demeaned every day in ways both large and small. Rainey knew these indignities firsthand. On a boat ride from Norfolk, Virginia, to Washington, D.C., the main dining hall had refused to serve him. In a D.C. pub, Rainey had ordered a glass of beer, only to find he’d been charged far more than white patrons. A hotel clerk had pulled the representative by his collar and kicked him out of a whites-only dining room.

African American leaders back home in South Carolina had sent a resolution urging him to fight for the bill, which would guarantee equal treatment of all Americans, regardless of race. Now, Rainey challenged his colleagues. “Why is it that colored members of Congress cannot enjoy the same immunities that are accorded to white members?” he asked. “Why cannot we stop at hotels here without meeting objection? Why cannot we go to restaurants without being insulted? We are here enacting laws of a country and casting votes upon important questions; we have been sent here by the suffrages of the people, and why cannot we enjoy the same benefits that are accorded to our white colleagues on this floor?”

The year was 1873.

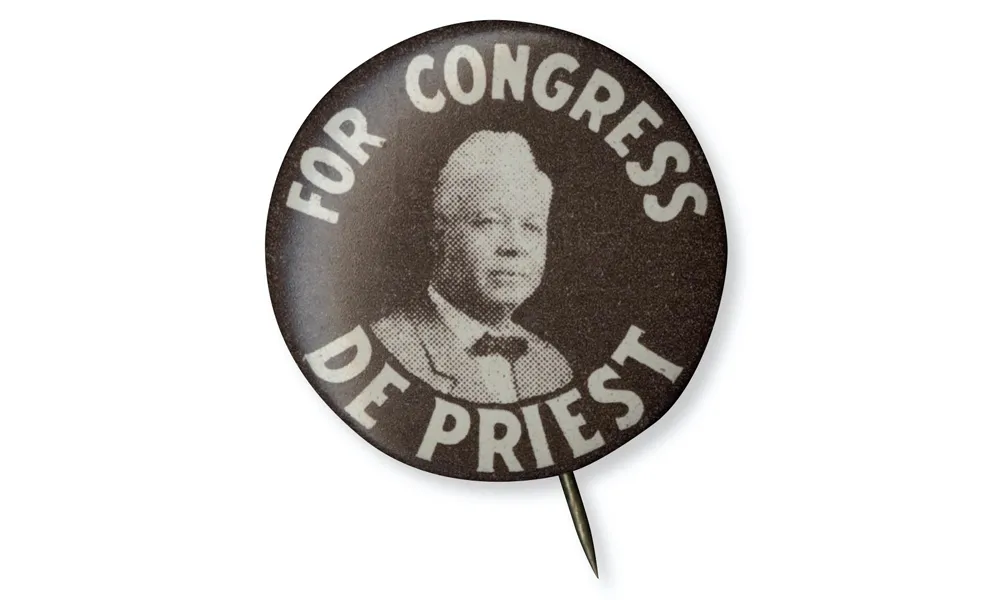

A century and a half later, Americans are only beginning to acknowledge Rainey’s contributions. He was the first African American to be seated in the United States House of Representatives and the first member of Congress born into enslavement. He was an architect of a crucial period in U.S. history, the era known as Reconstruction. Yet few are aware that Rainey and 15 other African Americans served in Congress during the decade just after the Civil War—or that there was a protracted battle over a civil rights act in the 19th century.

This obscurity is no accident. Rainey’s hopes were thwarted when white supremacists used violence and illegal tactics to force him and his colleagues out of office. Armed vigilante groups marauded throughout the South, openly threatening voters and even carrying out political assassinations. Southern Democrats—identifying themselves as “the white man’s party”—committed wide-scale voter fraud.

After African American politicians were stripped of their positions, their contributions were deliberately hidden from view. Popular histories and textbooks reported that Southern Republicans, known by opponents as “scalawags,” had joined forces with Northern “carpetbaggers” and allowed formerly enslaved people to have voting power they were unprepared to exercise. According to that story—taught for generations in schools North and South—the experiment of giving African Americans the vote had been a dismal failure, marked by incompetence and corruption.

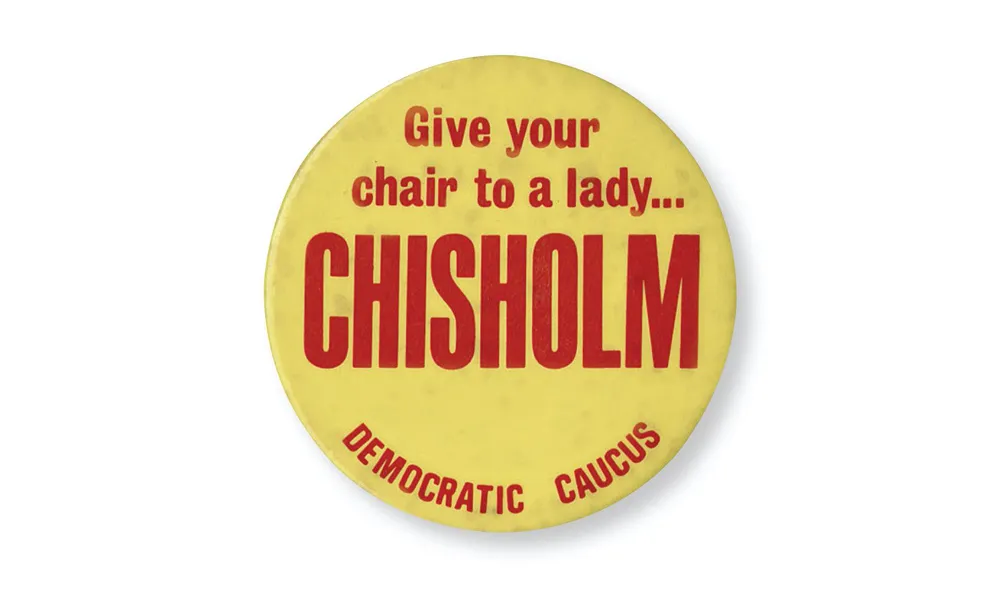

Rainey has slowly regained some recognition. His family house in Georgetown, South Carolina, was placed on the National Register of Historic Places and a park in the city was named in his honor. James E. Clyburn, a representative who currently represents part of Rainey’s district, lobbied the House to commission a new portrait of Rainey, which was unveiled in 2005 on the second floor of the Capitol. The portrait is now part of a newly launched exhibition at the Capitol, commemorating the 150th anniversary of Rainey’s December 1870 swearing in. The exhibition, which will remain on the walls for about three years, ends with a portrait of Shirley Chisholm, the first African American woman elected to Congress, in 1968. (The exhibit was not damaged in the insurrectionist attack on the Capitol on January 6, 2021.)

The revival of Rainey’s legacy benefits greatly from the digitization of an array of primary records. These sources directly contradict earlier, disparaging histories. They offer new insight into how a man born enslaved rose to be a respected national politician and how his career came to an abrupt and tragic end.

* * *

Rainey was born in Georgetown, South Carolina, on June 21, 1832, in an enslaved family. Only fragments of information remain from his early life, beyond the fact that his father, Edward L. Rainey, worked as a barber. In South Carolina, some enslaved people were allowed to practice a trade and even keep a small share of the income. Edward was able to cobble together enough money to buy, first, his own freedom, and then his family’s.

Rainey became a barber, like his father, and before the Civil War, he’d established his own business—Rainey’s Hair Cutting Salon—at the Mills Hotel in Charleston, a block from city hall. In prewar Charleston, Joseph Rainey occupied a relatively privileged yet precarious position. He was one of about 3,400 free people of color among 20,000 white and 43,000 enslaved people in the city. Their liberties were limited by law. Every free man over the age of 15 was required to have a white “guardian” to enable him to live in the city, and any “insolence” left the African American man open to violent assault. Free people of color had to pay an annual tax; if they failed to pay it, they could be sold into slavery for one year. Wherever they went, free people of color were assumed to be enslaved and had to show documents to prove they were not.

In September 1859, Rainey traveled to Philadelphia to marry Susan Elizabeth Cooper, the daughter of a free black family from Charleston. When the couple returned to South Carolina, Joseph faced legal trouble for having traveled to a free state. By state law, free people of color who traveled out of state were “forever prohibited from returning.” According to one biographical pamphlet, influential friends, perhaps white clients of his barbershop, interceded for him.

The state was already rife with tension about the future of slavery when Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election of 1860. In response, the South Carolina legislature voted to hold a special election for a state convention, and on December 20 the delegates—mostly secession-minded planters—voted unanimously to secede from the United States. Delegates marched through the streets of Charleston handing out placards declaring: “The Union Is Dissolved.”

On April 12, 1861, the newly formed Confederate Army opened fire on Fort Sumter, a Union outpost in Charleston Harbor—the beginning of the Civil War. Rainey was conscripted into service for the Confederacy. An early account suggests that he worked as a waiter or steward on a blockade-running steamer, making eight or more trips to and from Nassau, Bahamas.

According to an oral tradition passed down through the Rainey family, Joseph made an audacious move in 1862. Taking advantage of the fact that “foreign” vessels were still permitted to trade in South Carolina, Joseph boarded a trade ship to Nova Scotia, then to St. George’s, Bermuda. Susan followed later on the same route. As the story goes, Joseph used to go to the docks when ships arrived to watch for her.

During the Civil War years, Bermuda, a British colony, was thriving. Slavery had ended there in 1834, and the Union’s wartime trade prohibitions against the South had made Bermuda a go-between for Southern plantations exporting cotton and the Confederate military importing weapons.

In St. George’s, Rainey worked as a barber. After an 1865 outbreak of smallpox closed the port in St. George’s, where the Raineys were living, the couple relocated to the capital city, Hamilton. Joseph continued barbering, and Susan started a successful dressmaking business linked to a New York City designer.

One account based on Bermuda records suggests that Joseph received informal tutelage there from a highly educated customer at his barber shop. His personal journal shows a growing command of conventional spelling during this time. Bermuda is also mostly likely where he read the great works of literature, from Plato to Shakespearean tragedies, that he would later quote on the House floor.

In Bermuda, Rainey also joined a fraternal club and was involved in approving resolutions of condolence on Abraham Lincoln’s 1865 assassination, sending them on behalf of the Bermuda lodge to the U.S. consulate and to African American newspapers in New York City.

In September 1866, the Raineys took out a newspaper advertisement in the Bermuda Colonist: “Mr. and Mrs. J.H. Rainey take this method of expressing their thanks to the inhabitants of St. George’s for the patronage bestowed upon them in their respective branches of business.” The war was over, and Rainey—armed with new wealth, new knowledge and new social status—was ready to return to South Carolina, a state that needed him.

* * *

Before the Civil War, fewer than 10,000 free people of color lived in South Carolina. When Rainey returned in 1866, 400,000 newly freed people had increased the African American population to a majority of nearly 60 percent. Yet President Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, had subverted Congress and encouraged Southern white Democrats to rebuild their prewar governments. A bitter critic of civil rights legislation, Johnson declared, “This is a country for white men....As long as I am president it shall be a government by white men.”

In South Carolina, the ex-Confederates had followed Johnson’s lead and enacted Black Codes designed to “establish and regulate the Domestic Relations of Persons of Colour.” One of these codes declared: “All persons of color who make contracts for service or labor, shall be known as servants, and those with whom they contract, shall be known as masters.”

Another made allowances for “suitable corporal punishment” against servants. People of color were forbidden from working as artisans, shopkeepers, mechanics or in any other trade apart from husbandry unless they secured a license from the district court. Such licenses, if given at all, expired after one year.

Rainey’s brother, Edward, had taken a leading role in protesting these codes and the unreconstructed state government. In November 1865, Edward had served as a delegate to the state Colored People’s Convention, which declared, “We simply desire that we shall be recognized as men; that we have no obstructions placed in our way; that the same laws which govern white men shall direct colored men; that we have the right of trial by a jury of our peers, that schools be opened or established for our children; that we be permitted to acquire homesteads for ourselves and children; that we be dealt with as others, in equity and justice.”

Throughout the South, newly free people mobilized to make sure their freedom would be recognized and their rights would be lasting. Days after Congress passed the first Reconstruction Act, in March 1867, African American residents of Charleston staged sit-ins and streetcar boycotts, establishing a form of civil disobedience and nonviolent protest that activists would repeat a century later.

There were enough Republicans in the U.S. Congress to overcome Johnson’s veto and pass four Reconstruction Acts. One ordered former Confederate states to draw up new constitutions and have them approved by voters—including people of color. Beginning on January 14, 1868, Joseph Rainey served as a delegate to a statewide constitutional convention. For the first time, African American delegates were in the majority, 76-48. Numerous outsiders—professionals, intellectuals, educators, sympathetic Republican politicians—moved to the state to take part in the Reconstruction experiment. The number included some speculators and opportunists, as Rainey later observed.

For his part, Rainey was politically pragmatic about change. He backed creating a public school system and was willing to vote for an election poll tax to fund it. He also contended that freed people should purchase land confiscated from plantation owners. He was among the minority of delegates at the convention who believed that voters should be obligated to pay a poll tax, for educational purposes, and that those who did not meet property qualifications should have “no right to vote.”

After the convention, in April 1868, Rainey was elected to the South Carolina State Senate where he served as chairman of the Finance Committee. In July, he cast his vote in the General Assembly to ratify the 14th Amendment, which gave full citizenship to all people born in America, including the formerly enslaved. Under this new constitutional amendment, African Americans now had “equal protection of the laws.”

The reaction came swiftly. Ex-Confederates and sympathizers formed terrorist groups, igniting violence across the South. On October 16, 1868, just months after the majority-black assembly took office, Rainey’s African American colleague, state Senator Benjamin F. Randolph, was changing trains in Hodges, South Carolina, when three white men shot him to death on the railway platform. The assassins jumped on horses and rode away. Though the murder had taken place in broad daylight with several witnesses, law enforcement never identified any suspect. Democratic newspapers had disparagingly described Randolph as “a persistent advocate of the social equality idea.” His death was seen as a warning to Rainey and all those who advocated for the rights of the formerly enslaved

* * *

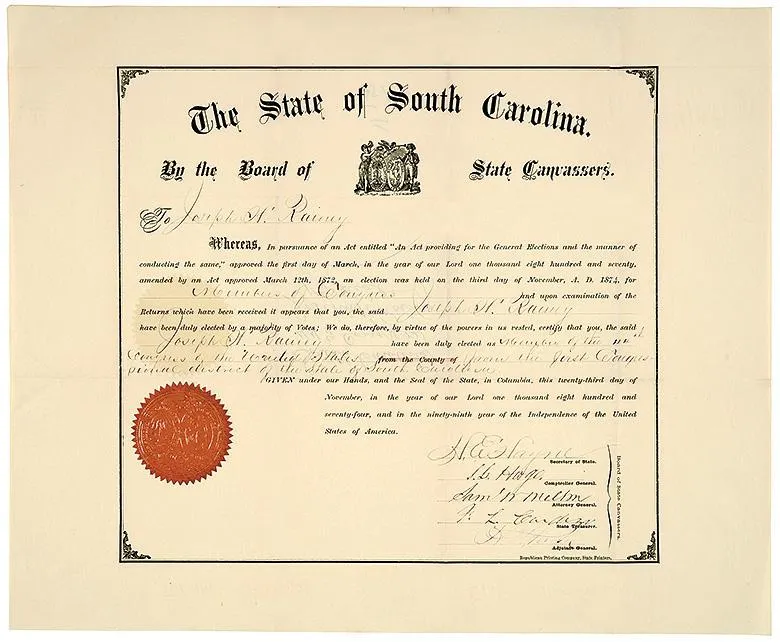

In late 1870, the Rev. B. F. Whittemore of South Carolina left his seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, creating a vacancy. Whittemore, a white New Englander who had served in the Union Army before moving to South Carolina, had been censured by the House for selling an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy, and he resigned from the House rather than be expelled. The Republican Party nominated Rainey to serve in Whittemore’s place for the last months of the 41st Congress. Then, in November, he also won the election to serve in the 42nd Congress. He was 38 years old.

On Monday, December 12, 1870, Joseph Hayne Rainey approached the rostrum, escorted by Representative Henry Dawes. “Mr. Rainey, the first colored member in the House of Representatives, came forward and was sworn in,” the Washington Evening Star reported, after which he walked to his seat in the southwest corner, on the Republican side of the hall.

Others viewed Rainey with curiosity, seemingly obsessed by his appearance. In a January 1871 article, the Chicago Daily Tribune noted, “His long bushy side whiskers are precisely like a white man’s. His physical organization seems to be sufficiently strong to bear all the strain his mental construction will give. His forehead is middling broad and high and the ennobling organization of the mind is well developed. He has an excellent memory, and his perceptive powers are good. His polite and dignified bearing enforces respect.” The writer went on to qualify this praise: “Of course Mr. Rainey will not compare with the best men of the House of Representatives, but he is a good average congressman, and stands head and shoulders above the ordinary carpet bagger.” Other commentators were more blatantly racist. The Cincinnati Daily Enquirer asked, “Is it possible to get further down in National degeneracy and disgrace?”

Among the resounding voices of support, though, was that of Frederick Douglass’ New National Era, which rejoiced that “despised Africa is now represented in no less a place than the American Congress.”

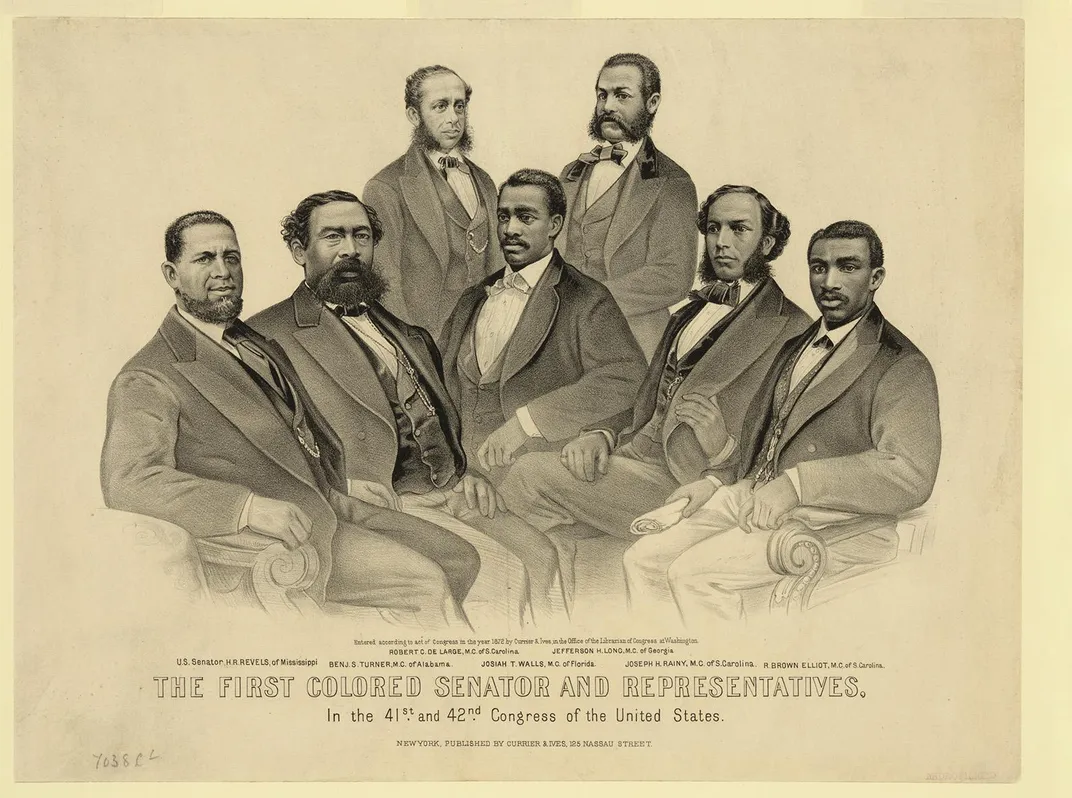

When the 42nd Congress began in March, two free men of color—Robert De Large and Robert Brown Elliott—joined Rainey as part of the South Carolina delegation. Two other former slaves—Benjamin Turner of Alabama and Jefferson Long of Georgia—had joined Congress shortly after Rainey (though Long served less than two months). In the U.S. Senate, Hiram Revels, a freeborn man of color, had taken office in 1870.

Together, these men grappled with the waves of white supremacist violence roiling the South. They championed provisions of the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Act, which called for federal forces to intervene against Klan activity and for federal district attorneys to prosecute the terrorists. Some members of Congress challenged the constitutionality of the act. Rainey took the floor. “Tell me nothing of a constitution which fails to shelter beneath its rightful power the people of a country!” he declared. The bill was approved and signed by President Grant.

Rainey and other Republican leaders soon received copies of an ominous letter written in red ink. “Here, the climate is too hot for you....We warn you to flee. Each and every one of you are watched each hour.”

Still, the coalition of African American representatives continued to grow. Its members debated issues that would determine the future of democracy. In 1872, for instance, Rainey fired back at a white colleague who feared that integrated schools might lead to full social equality between the races. Rainey disputed the way his colleague had depicted the African American: “Now, since he is no longer a slave, one would suppose him a leper, to hear the objections expressed against his equality before the law. Sir, this is the remnant of the old pro-slavery spirit, which must eventually give place to more humane and elevating ideas. Schools have been mixed in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and other States, and no detriment has occurred. Why this fear of competition with a negro? All they ask for is an equal chance in life, with equal advantages, and they will prove themselves to be worthy American citizens.”

In 1874, Rainey spoke out on behalf of other oppressed minorities, opposing a bill to ban Chinese workers from taking part in a federally funded construction project in San Francisco. “They come here and are willing to work and assist in the development of the country,” he declared. “I say that the Chinaman, the Indian, the negro, and the white man should all occupy an equal footing under this Government; should be accorded equal right to make their livelihood and establish their manhood.”

On April 29 of that year, Rainey broke new ground. The entire House had gathered as a body to debate the Indian Affairs Bill over several days, and the Speaker of the House invited a sequence of representatives to serve as speaker pro tempore. Luke Potter Poland, a Republican from Vermont, was presiding when he invited Rainey to take the chair. It was the first time an African American had ever presided over the U.S. House of Representatives.

Newspapers spread the word, with headlines such as “Africa in the Chair.” The Vermont Journal declared, “Surely the world moves, for who would have dreamed it, 20 years ago?” The Springfield Republican noted that just a generation earlier, “men of Mr. Rainey’s race were sold under the hammer within bowshot of the capitol.” The New National Era noted the event with a jab at racist alarmism: “For the first time in the nation’s history a colored man, in the person of Hon. Joseph H. Rainey, of South Carolina, on Thursday last presided over the deliberations of the House of Representatives....The earth continues to revolve on its axis.”

* * *

Rainey and his colleagues had Northern allies in the Republican Party. One of the most influential, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, had been an outspoken abolitionist. In 1870, he drafted a civil rights bill with the help of John Mercer Langston, an attorney who founded the law school at Howard University, the first to serve African American students. The bill would have banned discrimination in schools, churches and places of public access such as hotels and trains. Representative Benjamin Butler, also of Massachusetts, sponsored the bill in the House. As a lawyer and Union general, Butler had pioneered the strategy of treating enslaved people who escaped to Union Army camps as war contraband, which created a groundswell toward Lincoln’s emancipation policy.

Sumner and Rainey had become friends, and as Sumner approached death in 1874, he pleaded with Rainey, “Do not let the civil-rights bill fail!” Sumner died in March of that year without achieving his fervent goal.

A month later, Rainey—who had accompanied the Sumner family to Boston for the burial—gave a stirring speech before Congress, remembering a time when Sumner had nearly lost his life after South Carolina Congressman Preston S. Brooks assaulted him in the Senate chamber. “The unexpressed sympathy that was felt for him among the slaves of the South, when they heard of this unwarranted attack, was only known to those whose situations at the time made them confidants,” Rainey recalled. “Their prayers and secret importunities were ever uttered in the interest of him who was their constant friend and untiring advocate and defender before the high court of the nation.”

By that time, Rainey had earned a reputation for forcefully protecting the fledgling democracy in the South. Yet he was concerned enough about violent retaliation that he bought a second home, in Windsor, Connecticut, and his wife and children moved there in the summer of 1874. Even so, in a February 1875 speech Rainey made it clear that black politicians were not going anywhere. “We do not intend to be driven to the frontier as you have driven the Indian,” said Rainey, who was also a member of the House Indian Affairs Act Committee and a champion of Indian rights. “Our purpose is to remain in your midst as an integral part of the body-politic.”

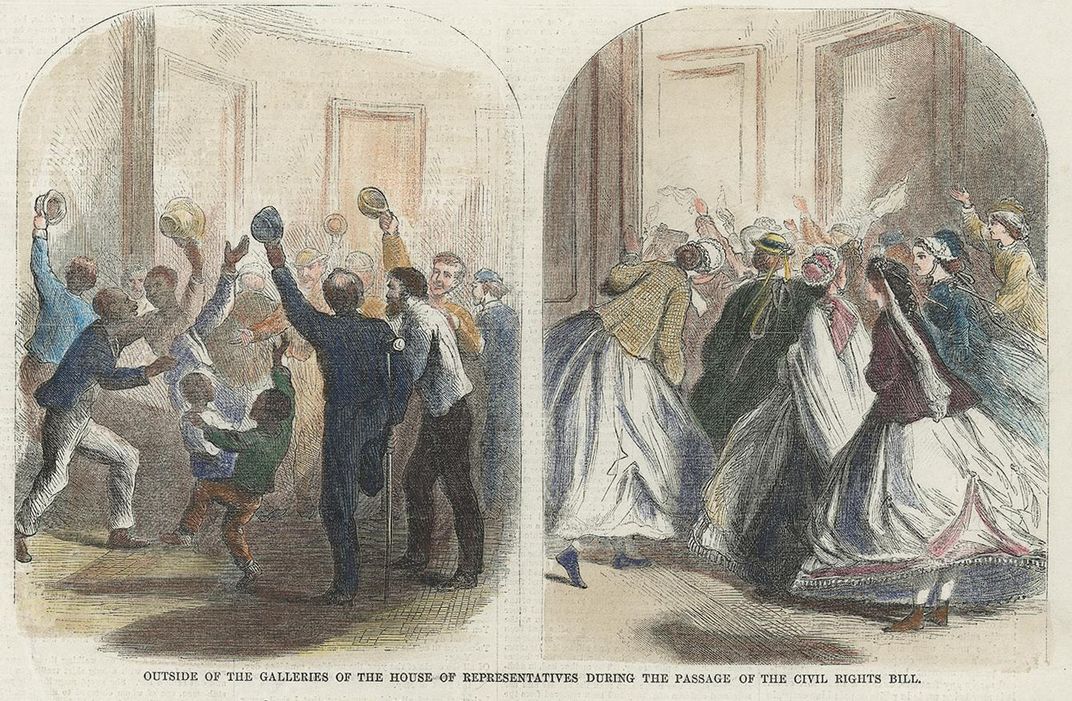

After Democrats gained control of the House in the 1874 election, Republican sponsors rushed to pass the civil rights bill. To gain votes, they removed the integration of schools and churches, the places that drew the fiercest opposition. Personal testimonies from African American members of Congress, and sympathy for the departed Sumner, helped give it traction, and, on March 1, 1875, President Grant signed the Civil Rights Act.

It was the final Reconstruction act. Disgruntled Southern Democrats were already making plans to reverse the progress.

* * *

Hamburg, South Carolina, lies along the Savannah River across from Augusta, Georgia. By 1876, newly freed African Americans had revitalized the declining town, making it a haven of business and property ownership, and electoral freedom. A town militia protected Hamburg from ex-Confederate vigilante raids. On July 4 of that year, 16 months after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, white travelers provoked a confrontation by attempting to drive a carriage through the African American militia’s Independence Day parade on Main Street. After trying to force the militia to disband and surrender its weapons in court, one of the white travelers returned on the day of the hearing with more than 200 men and a cannon. The vigilantes surrounded the militia in a warehouse, shot men as they tried to escape, captured the rest and tortured and executed six. Not one person was ever prosecuted for the murders.

In Congress, Joseph Rainey said the assassination of Hamburg leaders was a “cold-blooded atrocity.” He implored his fellow members, “In the name of my race and my people, in the name of humanity, in the name of God, I ask you whether we are to be American citizens with all the rights and immunities of citizens or whether we are to be vassals and slaves again? I ask you to tell us whether these things are to go on.”

Instead, the massacre inspired a wave of open terror against African Americans across the state. In the 1876 gubernatorial race, Wade Hampton III—who had succeeded Jeb Stuart as a Confederate cavalry commander—reportedly won the election. But the tally made no mathematical sense. Of 184,000 eligible male voters, more than 110,000 were African American. Hampton had allegedly tallied more than 92,000 votes, which would have required 18,000 African Americans to choose a Confederate leader who had enslaved hundreds of people in South Carolina and Mississippi. A single county, Edgefield, reported 2,000 more votes than it had eligible voters.

The federal government did nothing in response to this flagrant abuse of the polls. In fact, its inaction was part of a secret deal. In the 1876 presidential election, the electoral college tally came down to three states in which both parties accused each other of fraud: South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana. In January 1877, just two months before the new president was supposed to take office, there was still no clear winner. The two parties made a compromise in private. The Democrats would allow Rutherford B. Hayes, the Ohio Republican, to become the next president of the United States. In return, his administration would allow white Democratic “redeemers” to reclaim their states from African Americans, however they saw fit. In essence, Northern Republicans agreed to take the presidency in exchange for withdrawing federal troops from the South, ending Reconstruction.

As Rainey campaigned for re-election in 1878, he met with President Hayes. He was joined by Stephen Swails, a freeborn African American from the North who had served as an officer in the Civil War. Together, Rainey and Swails pleaded with the president to ensure fair elections. In keeping with the “compromise,” the president declined. When votes came in, the official count showed that John Smythe Richardson, a former Confederate officer and a Democrat, had somehow won 62 percent of the vote for Rainey’s seat—in a strong Republican district where African Americans were the majority of residents.

Years later, Southern Democratic leaders boasted about all kinds of illegal acts during the elections of the 1870s, from folding more than one “tissue ballot” inside regular paper ballots to bringing Georgians across state lines to vote in South Carolina. In his successful 1890 campaign for governor, Benjamin “Pitchfork” Tillman, leader of the Red Shirts at Hamburg, brazenly referred to the massacre. “The leading white men of Edgefield” had wanted to “seize the first opportunity that the Negro might offer them to provoke a riot and teach the Negroes a lesson.” He added, “As white men we are not sorry for it, and we do not propose to apologize for anything we have done in connection with it. We took the government away from them in 1876. We did take it.”

* * *

On March 3, 1879, Rainey gave his final remarks to the U.S. House of Representatives. “I was legally elected,” he declared, “but was defrauded and tissued out of my seat.” He asked his colleagues, “Must the will of the majority to rule, the very foundation and cornerstone of this Republic, be supplanted, suppressed, or crushed by armed mobs of one party destroying the ballots of the other by violence and fraud?” As he prepared to leave office, Rainey told Congress he hoped “an impartial historian” would tell the truth about his era.

Two months later in Nashville, Tennessee, Rainey addressed the National Conference of Colored Men with grim realism. “We may never hold another conference,” he told them. “The same faces will never be mirrored against these walls.” He warned, “We are a proscribed people....We have stood a great deal....We want to say to the white people the time has come for us to give warning that we have stood all we can....We have been enriching the white man, and the time has come when forbearance has ceased to be a virtue....We have stood too much now, and I would not blame any colored man who would advise his people to flee from the oppressors to the land of freedom.” Decades ahead of the Great Migration of the World War I era, the conference established a committee to explore conditions for a mass exodus to the western and northern United States.

The new America that Rainey had hoped to help create was a fading dream. In 1883, in an 8-1 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that key sections of the Civil Rights Act were unconstitutional. The majority opinion declared the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause only prohibited discrimination by state and local government, not by private individuals and organizations. Furthermore, the court ruled, the 13th Amendment had ended slavery but did not make any guarantees against racial discrimination.

With diminishing resources and in poor health, Rainey returned to Georgetown, South Carolina, where his wife opened a millinery shop. At the age of 55, he contracted malaria and died less than a year later, in August 1887. The Washington Evening Star described him as “one of the most intelligent representatives of the colored race in the South.”

Months later, a Georgia newspaper noted that Reconstruction politicians were “glimmering into obscurity.” The reporter ignored all the violence and fraud, claiming that the African American had “dismissed politics from his mind and gone to making money....He is too busy to vote.”

With black voters stripped of power, white politicians gathered to discuss the “Negro question.” At these meetings, there was little consideration of the African Americans who had held office during Reconstruction or the millions of new citizens they had represented. The whole era—from 1868 to 1876—was recast as an effort that had failed because black voters weren’t capable of making good decisions.

In 1890, Hayes, no longer president, spoke to an all-white gathering at Lake Mohonk, New York, and gave voice to a malignant belief that was all too common: “One of the devoted friends of the colored people tells us that ‘their ignorance, indifference, indolence, shiftlessness, superstition and low tone of morality are prodigious hindrances to the development of the great low country where they swarm.’ It is, perhaps, safe to conclude that half of the colored population of the South still lack the thrift, the education, the morality, and the religion required to make a prosperous and intelligent citizenship.”

* * *

Prominent academics would amplify and even justify this derogatory depiction of 19th-century African American voters and politicians. William Archibald Dunning, a historian and political scientist at Columbia University, worked with graduate students to write state-by-state histories of Reconstruction. Writing in the Atlantic Monthly, Dunning denigrated the era’s African American politicians as “very frequently of a type which acquired and practiced the tricks and knavery rather than the useful art of politics, and the vicious courses of these negroes strongly confirmed the prejudices of the whites.”

John Schreiner Reynolds, who had been influenced by Dunning, lambasted African American leaders in his 1905 book Reconstruction in South Carolina. He called one of those leaders “a vicious and mouthy negro” who “lost no opportunity to inflame the negros against the whites.” As Reynolds told it, the Red Shirt violence at Hamburg was “the culmination of troubles which had long been brewing in and around the negro-ridden town.” The actual lives and contributions of African American politicians were entirely missing from establishment histories.

At the American Historical Association meeting in 1909, W.E.B. Du Bois tried to correct this with a presentation called “Reconstruction and Its Benefits.” “There is danger today,” Du Bois warned, “that between the intense feeling of the South and the conciliatory spirit of the North grave injustice will be done the negro American in the history of Reconstruction.”

But the determined effort to recast Reconstruction as a debacle of corruption continued. In 1915, Woodrow Wilson showed Birth of a Nation at the White House. The revisionist film grossly demeaned Reconstruction and inspired the revival of the Ku Klux Klan as a nationwide terrorism organization.

Du Bois made another attempt to set the record straight in his 1935 book Black Reconstruction in America: A History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880. In that bold work, he explicitly described the contributions black leaders had made to American politics. “Rainey of South Carolina was one of the first Americans to demand national aid for education,” he noted.

In 1940, not long after Gone With the Wind premiered in theaters, South Carolina erected a statue of Tillman, the former governor, U.S. senator and violent Red Shirt leader, near the entry to the South Carolina statehouse. The goal: remind South Carolina that Tillman had believed “in the inevitable triumph of white democracy.” At the dedication, the keynote speaker was Senator James Byrnes, soon to serve as a U.S. Supreme Court justice. Supporters of the statue praised Tillman for redeeming the state. To raise money for the statue, they’d written, “He participated in the Hamburg and Ellenton Riots of 1876, and aided in the Democratic triumph of that year by frightening prospective Negro voters away from the polls.”

But Rainey and his contemporaries hadn’t been erased completely. In 1946, the Southern Negro Youth Congress, a decade-old political organization, gathered in the state capital Columbia. To prepare for W.E.B. Du Bois’ keynote speech, the young organizers decorated the hall’s upper level with six-foot-tall portraits of African American representatives from that era. Joseph Rainey was among them.

* * *

Rainey’s children and grandchildren continued his work, serving in leadership roles within the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which was founded in 1909. Joseph’s daughter, Olive, used to lift young Lorna Rainey onto her lap and tell stories about the congressman. “Maybe my great-aunt knew that this would always be a story that’s always timely,” Lorna recalls today. “This is not a black story or a white story. This is a story of inspiration, of courage, of forward thinking.”

Lorna, a talent agent based in New York, is now working on a documentary film about Rainey, drawing on new scholarship as well as the wealth of knowledge his family has handed down about him. The film, called Slave in the House, will celebrate Rainey’s personal acts of bravery as well as his political legacy. “He was a courageous man,” Lorna says, describing how Rainey once refused to leave a hotel dining room that wouldn’t serve him until escorts pushed him down the stairs. “He deliberately put his physical self in harm’s way in order to prove a point, and he knew that regardless of what he said—‘Oh, I’m a congressman’—that wasn’t going to help him. They didn’t see ‘congressman.’ They saw color. So he didn’t mind if he was threatened by the KKK, or the Red Shirts. They couldn’t stop him from trying to exercise his position to try to help other people.”

Unlike Lorna, Representative Clyburn learned little about Rainey’s life and career while he was growing up. “No one really talked about Rainey,” says Clyburn, who was born in Sumter, South Carolina, in 1940. He began learning more about Rainey once he was elected to Congress, in 1992, representing part of Rainey’s former district. Since then, he has become a vocal advocate for remembering Rainey and the whole generation of black Reconstruction politicians. “If people knew this history,” Clyburn says, “they would have a better understanding of some of the political challenges we face today.”

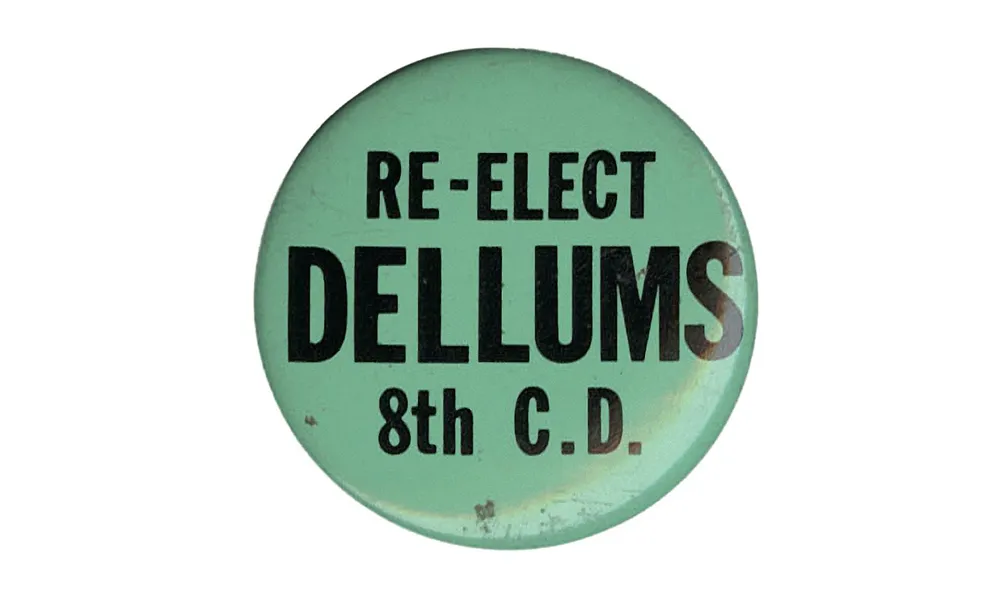

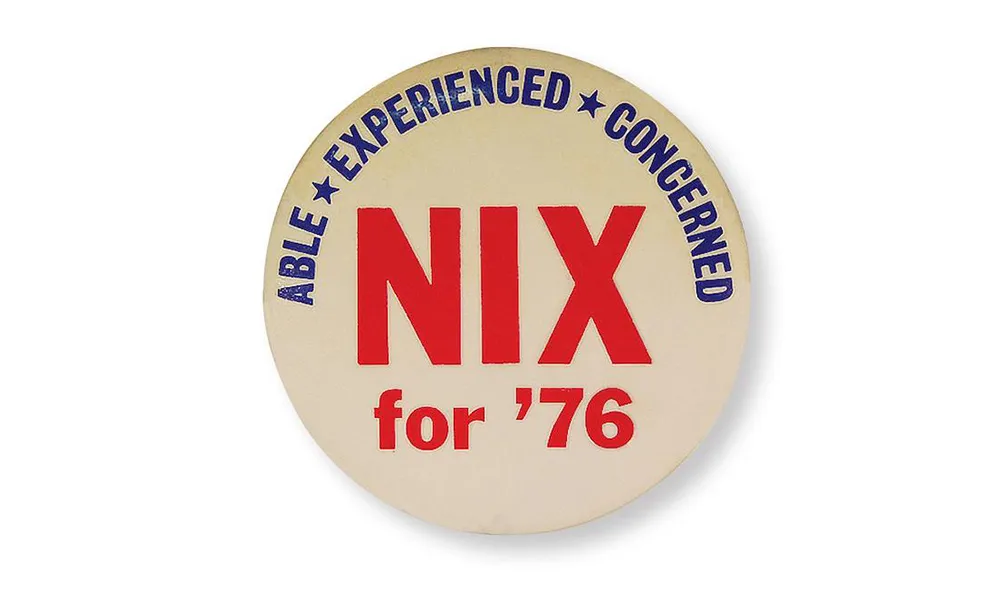

Clyburn’s career has followed a different trajectory from Rainey’s. He is serving his 14th term in Congress, where he is the third-highest ranking Democrat. (Through 20th-century black activism, the Democratic Party, which once barred black members throughout the South, became the party of civil rights under President Lyndon Johnson.) From 1999 to 2001, Clyburn chaired the Congressional Black Caucus, founded in 1971.

But while Rainey’s own career was obstructed by white supremacists, and ultimately cut short, Clyburn believes that Rainey’s story is ultimately one of victory. “People who paved the road often get punished,” Clyburn says. “I really believe he smashed through and there emerged a deliberate attempt not to give him the recognition he was due. The people who are first sometimes pay a real big price.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f7/2a/f72aa6df-e5ba-4c0f-b906-550f78a89c07/rainey-mobileopener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b9/ea/b9ea810d-bc37-4aa9-80dc-b5a955af0df9/longformopener.jpg)