King Tut: The Pharaoh Returns!

An exhibition featuring the first CT scans of the boy king’s mummy tells us more about Tutankhamun than ever before

Seated on a cushion at the Pharaoh Tutankhamun’s feet, Ankhesenamun hands her young husband an arrow to shoot at ducks in a papyrus thicket. Delicately engraved on a gilt shrine, it’s a scene (above) of touching intimacy, a window into the lives of the ancient Egyptian monarchs who reigned more than 3,300 years ago. Unfortunately, the window closes fast. Despite recent findings indicating that Tut, as he has come to be known, was probably not murdered, the life and death of the celebrated boy-king remain a tantalizing mystery.

“The problem with Tutankhamun is that you have an embarrassment of riches of objects, but when you get down to the historical documents and what we actually know, there is very little,” says Kathlyn Cooney, a Stanford University Egyptologist and one of the curators of the first Tutankhamun exhibition to visit the United States in more than a quarter-century. (The show opens at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art on June 16 and travels to the Museum of Art in Fort Lauderdale, the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia.)

On display are 50 stunning funerary objects from the pharaoh’s tomb and 70 pieces from other ancient tombs and temples, dating from 1550 to 1305 B.C. On loan from the Egyptian National Museum in Cairo, this astonishingly well-preserved assemblage includes jewelry, furniture and exquisitely carved and painted cosmetics vessels.

Negotiations for the exhibition dragged on for three years while the Egyptian Parliament and many archaeologists resisted lifting a travel ban imposed in 1982 after a gilt goddess from Tut’s tomb was broken while on tour in Germany. In the end, Egypt’s president, Hosni Mubarak, intervened.

“Once the president decided to put Egypt’s collections back on the museum circuit, we obtained the green light for the project,” says Wenzel Jacob, director of the Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle museum in Bonn, Germany, where the exhibition was on display before moving to Los Angeles.

Most of the objects were excavated in the Valley of the Kings, two desert canyons on the west bank of the Nile, 416 miles south of Cairo. Covering half a square mile, the valley is the site of some 62 tombs of Egyptian pharaohs and nobles. Unlike the blockbuster show of the 1970s that focused exclusively on Tut and the discovery of his tomb by English archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922, the current exhibition also highlights the ruler’s illustrious ancestors.

“This period was like a fantastic play with magnificent actors and actresses,” says Zahi Hawass, secretary general of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities. “Look at the beautiful Nefertiti and her six daughters; King Tut married one of them. Look at her husband, the heretic monarch Akhenaten; his domineering father, Amenhotep III; and his powerful mother, Queen Tiye. Look at the people around them: Maya, the treasurer; Ay, the power behind the throne; and Horemheb, the ruthless general.”

Born circa 1341 B.C., most likely in Ankhetaten (present-day Tell el-Amarna), Tutankhamun was first called Tutankhaten, a name that meant “the living image of the Aten,” the sole official divinity by the end of the rule of Akhenaten (1353 to 1335 B.C.). Tut was probably Akhenaten’s son by Kiya, a secondary wife, but may have been the son of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye, making him Akhenaten’s younger brother.

While Tut was being educated at the palace, the empire was losing its grip on its northern territories in what is now Syria. But there is no indication that Akhenaten, perhaps reluctant to send his troops to foreign fields while he attempted to recast the established religion, took any action against invading Hittite warriors from Anatolia.

Although little is known of Tut’s childhood, British historian Paul Johnson speculates that life in a new capital city, Amarna, must have been insular and claustrophobic. Five or six years before Tut’s birth, Akhenaten had created Amarna, in part, perhaps, to escape the bubonic plague that was ravaging Egypt’s congested cities as well as to make a clean break with the cult of Amun, then Thebes’ chief god. Declaring Aten as the supreme and only god, Akhenaten closed the temples of rival gods and had his soldiers deface images of Amun and other deities, tossing out, to widespread consternation, a system that for two millennia had brought stability to this world and promised eternal life in the next. “The [new] religion was followed only in Amarna,” says André Wiese, curator of the Antikenmuseum in Basel, Switzerland, where the exhibition originated. “In Memphis and elsewhere, people continued to worship the pantheon of old.”

After Akhenaten’s death, a scramble for the throne ensued. A mysterious pharaoh named Smenkhkare may have become king and reigned for a year or two before dying himself. (It’s also possible that he was a co-ruler along with Akhenaten and predeceased him.)

As the child husband of Akhenaten’s third daughter, Ankhesenpaaten (who may also have been his half sister), Tut inherited the crown circa 1332 B.C., when he was 8 or 9 years old (about the same age as his bride). The couple were probably married in order to legitimize the boy’s claim to rule.

Although Egypt, a superpower with a population of 1 million to 1.5 million, commanded territory stretching from Sudan almost to the Euphrates River, the empire under Akhenaten, “had crumpled up like a pricked balloon,” according to Howard Carter in his 1923 book on the discovery of Tut’s tomb. Merchants railed at the lack of foreign trade, and the military, “condemned to a mortified inaction, were seething with discontent.” Farmers, laborers and the general populace, grieving the loss of their old gods, “were changing slowly from bewilderment to active resentment at the new heaven and new earth that had been decreed for them.”

Carter believed that Akhenaten’s wily adviser, Ay (who may have been Nefertiti’s father), was responsible for installing Tut as a puppet pharaoh as a way to heal the divided country. When Tut and his wife were both about 11, Ay moved the court back to the administrative capital of Memphis, 15 miles south of today’s Cairo, and likely advised the boy-king to reinstate polytheism. Tut obliged and changed his name to Tutankhamun (“living image of the Amun”); his wife became Ankhesenamun (“she lives for Amun”).

Outside the Amun temple in Karnak, Tut erected an eight-foot-tall stela as an apology for Akhenaten’s actions and a boast of all Tut had done for the Egyptian people. “The temples . . . had gone to pieces, the shrines were desolate and overgrown with weeds,” the stela proclaimed. But the pharaoh now has “filled [the temple priests’] workshops with male and female slaves” and all “the property of the temples has been doubled, tripled, quadrupled in silver, gold, lapis lazuli, turquoise . . . without limit to any good thing.”

As Carter’s examination of Tut’s mummy revealed, the young ruler stood about 5 feet 6 inches tall. Like his ancestors, says Hawass, he was probably raised as a warrior. (His tomb contained six chariots, some 50 bows, two swords, eight shields, two daggers and assorted slingshots and boomerang-like throwsticks.) Scenes on a wooden chest found in his tomb depict him riding into battle with drawn bow and arrow, trampling hordes of Nubian infantry under the wheels of his chariot. W. Raymond Johnson of the University of Chicago says Hittite texts recount an Egyptian attack on Kadesh, in today’s Syria, shortly before the king’s death. Tutankhamun “may actually have led the charge,” he says. But other scholars, including Carter, view the militaristic images as polite fictions or propaganda, and doubt that the monarch himself ever saw combat.

Most probably, the royal couple spent much of their time in Memphis, with frequent trips to a hunting villa near the Great Sphinx at Giza and to the temples of Thebes to preside over religious festivals. The teenage queen apparently suffered two failed pregnancies: the miscarriage of a 5-month-old female fetus and a stillborn baby girl. (Both were mummified and buried in Tutankhamun’s tomb.)

Then, around 1323 B.C., Tut suddenly died. According to the recent computed tomography (CT) scans, he was 18 to 20 years old at the time of death (judging from bone development and observations that his wisdom teeth had not grown in and his skull had not fully closed). Despite the fact that Carter’s team had badly mangled the mummy, the scans indicate that Tutankhamun had been in general good health. He may, however, have succumbed to an infection due to a badly broken left thighbone. “If he really did break his leg so dramatically,” Cooney points out, “the chances of him dying from it are reasonably high.” But some members of the scanning team maintain that Carter and his excavators fractured the leg unwrapping the mummy; such a ragged split, had it occurred while Tut was still alive, they argue, would have generated a hemorrhage that would have shown up on the scans.

One theory that appears to have been finally put to rest is that Tut was killed by a blow to the head. A bone fragment detected in his skull during a 1968 X-ray was caused not by a blow, but by the embalmers or by Carter’s rough treatment. Had Tut been bludgeoned to death, the scanning report found, the chip would have stuck in the embalming fluids during burial preparations.

After Tut’s death, his widowed queen, many scholars believe, wrote in desperation to the enemy Hittite chieftain, Suppiluliuma, urging that he send one of his sons to marry her and thereby become pharaoh. (Some scholars, however, think that the letter may have been written by Nefertiti or Tiye.) Since no Egyptian queen had ever married a foreigner, writing the letter was a gutsy move. The Hittites were threatening the empire, and such a marriage would have averted an attack as well as preserving Ankhesenamun’s influence. After dispatching an envoy to make sure the request was not a trap, Suppiluliuma sent his son Zananza. But despite the chieftain’s precaution, Zananza was killed on his way to Memphis, perhaps by general Horemheb’s forces.

How did Tutankhamun escape the fate of so many pharaohs, whose graves were ransacked within a few generations of their death? For one thing, he was buried in a relatively small tomb. During his lifetime, work was under way on a grand royal tomb with long corridors and several rooms leading to a burial chamber. Perhaps because it was still unfinished at the time of his early death, the young king was buried in a much smaller crypt, possibly one meant for Ay.

After Tut’s funeral, the elderly vizier married Ankhsenamun and became pharaoh. Dying three or four years later, some suggest at Horemheb’s hand, Ay was buried in the large tomb that may have been meant for Tut. In 1319 B.C. the ambitious Horemheb seized power and immediately set about wiping Tutankhamun’s name from the official records, in all likelihood, Cooney speculates, so that Horemheb himself “could take credit for restoring stability.” Then, nearly 200 years after Tut’s death, his tomb was covered over by huts of laborers digging a crypt for Ramses VI. As a consequence, the pharaoh lay buried and forgotten in an unmarked grave, largely safe from potential plunderers.

The boy-king’s obscurity, however, came to an end on the morning of November 4, 1922, when a water boy with Carter’s archaeological team dug a hole for his water jar and exposed what turned out to be the first step of Tut’s long-lost grave. Despite Horemheb’s efforts to erase Tut from history, excavations in the early 20th century had uncovered seal impressions inscribed with his name. Carter had spent five years futilely searching for Tut’s tomb, and his English patron, Lord Carnarvon, was ready to withdraw financing.

Soon after the water boy’s discovery, the 48-year-old Carter arrived at the site to find the men working feverishly. By dusk the next day, they had hollowed out a passage 10 feet high by 6 feet wide, descending 12 steps to a doorway, which was closed off with plastered stone blocks. “With excitement growing to fever heat,” Carter recalled in his diary, “I searched the seal impressions on the door for evidence of the identity of the owner, but could find no name. . . . It needed all my self-control to keep from breaking down the doorway and investigating then and there.”

Carter loosely repacked the rubble, then sent a telegram to Carnarvon at his Hampshire castle: “At last have made wonderful discovery in the Valley; a magnificent tomb with seals intact; re-covered same for your arrival; congratulations.” Three weeks later, the 57-year-old Carnarvon arrived with his daughter, Evelyn Herbert. Carter and his team then dug away four more steps, excitedly uncovering seals that bore the name Tutankhamun. Removing a door, they encountered a passageway packed with rubble. Sifting through flint and limestone chips, they discovered broken jars, vases and pots—“clear evidence of plundering,” wrote Carter—and their hearts sank. But at the end of the 30-foot-long passage, they found a second blocked door also bearing Tut’s seals. Boring a hole in the upper left corner, Carter poked a candle into the opening as Carnarvon, his daughter and Arthur Callender, an architect and engineer who assisted in the excavations, looked on impatiently. Can you see anything? Asked Carnarvon. Momentarily struck dumb with amazement, the archaeologist replied at last. “Wonderful things,” he said.

Widening the opening and shining a flashlight into the room, Carter and Carnarvon saw effigies of a king, falconheaded figures, a golden throne, overturned chariots, a gilded snake, and “gold—everywhere the glint of gold.” Carter later recalled that his first impression was of uncovering “the property room of an opera of a vanished civilization.”

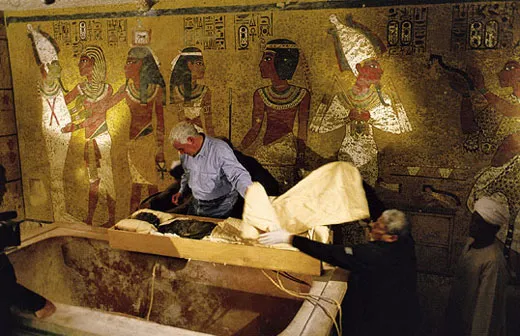

Carter spent nearly three months photographing and clearing out the antechamber’s objects alone. Then in mid-February 1923, after digging out the blocked doorway to the burial chamber, he encountered what appeared to be a solid wall of gold. This proved to be the outermost of four nested gilded wood shrines, an imposing construction—17 feet long, 11 feet wide and 9 feet high, embellished inside with scenes of winged goddesses, pharaohs and written spells—that enclosed Tutankhamun’s yellow quartzite sarcophagus.

Slipping through the narrow space between the nested shrines and a wall painted with murals welcoming the king into the afterlife, Carter shined his flashlight through an open doorway to the treasury room beyond, guarded by the statue of a recumbent jackal representing Anubis, the god of embalming. Beyond it gleamed a massive gilt shrine, later found to house a calcite chest containing the desiccated remains of Tut’s liver, stomach, intestines and lungs. Surrounded by a quartet of goddesses, each three feet tall, the shrine, Carter wrote, was “the most beautiful monument that I have ever seen. . . . so lovely it made one gasp with wonder and admiration.”

Grave robbers had in fact broken into the tomb at least twice in ancient times, and made off with jewelry and other small objects from the antechamber, the first room Carter discovered, and a smaller, adjoining annex. They had also penetrated the burial chamber and treasury, but, apparently unable to access the inner shrines protecting Tut’s sarcophagus, had taken very little of value. After each occasion, necropolis guards had resealed the tomb. According to calculations based on packing inventories found in the tomb, the thieves made off with about 60 percent of the original jewelry. But more than 200 pieces of jewelry remained, many inside Tut’s sarcophagus, inserted into his mummy’s wrappings. In addition, hundreds of artifacts—furniture, weapons, clothing, games, food and jars of wine (all for the pharaoh’s use in the afterlife)—were left untouched.

Seven weeks after the opening of the burial chamber, Carnarvon died from a mosquito bite that he had infected while shaving. Immediately, sensation-seeking journalists blamed his death on the pharaoh’s “curse”—the superstition, spread after Carter’s discovery by Marie Corelli, a popular Scottish author, that anyone who disturbed Tut’s tombwould suffer an untimely end.

It took another two years and eight months of removing and cataloging objects before the ever-meticulous Carter raised the lid of the third and final coffin (245 pounds of solid gold) inside the sarcophagus and gazed at the gold and lapis lazuli mask atop Tut’s mummy. Three weeks later, after cutting away resin-encrusted wrappings from the mask, Carter was able to savor the “beautiful and well-formed features” of the mummy itself. Yet it was not until February 1932, nearly a decade after opening the tomb, that he finally finished photographing and recording all the details of Tut’s treasures, a mind-boggling 5,398 items.

Just eight years before Carter’s discovery, American lawyer and archaeologist Theodore Davis, who had financed numerous expeditions to the Valley of the Kings, had turned in his shovel. “I fear the Valley is now exhausted,” he had declared. Mere feet from where Davis had stopped digging, the dogged Carter, quite literally, struck gold.