Kurdish Heritage Reclaimed

After years of conflict, Turkey’s tradition-rich Kurdish minority is experiencing a joyous cultural reawakening

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Heritage-Kurds-Semi-Utan-Kurds-631.jpg)

In the breathtakingly rugged Turkish province of Hakkari, pristine rivers surge through spectacular mountain gorges and partridges feed beneath tall clusters of white hollyhock. I’m attending the marriage celebration of 24-year-old Baris and his 21-year-old bride, Dilan, in the Kurdish heartland near the borders of Syria, Iran and Iraq. This is not the actual wedding; the civil and religious ceremonies were performed earlier in the week. Not until after this party, though, will the couple spend their first night together as husband and wife. It will be a short celebration by Kurdish standards—barely 36 hours.

Neither eating nor drinking plays much of a role at a traditional Kurdish wedding. On the patio of a four-story apartment house, guests are served only small plates of rice and meatballs. Instead, the event is centered on music and dance. Hour after hour, the band plays lustily as lines of guests, their arms linked behind their backs, kick, step and join in song in ever-changing combinations. Children watch intently, absorbing a tradition passed down through generations.

The women wear dazzling, embroidered gowns. But it’s the men who catch my eye. Some of them are wearing one-piece outfits—khaki or gray overalls with patterned cummerbunds—inspired by the uniforms of Kurdish guerrillas who fought a fierce campaign for self-rule against the Turkish government throughout much of the 1980s and ’90s. The Turkish military, which harshly suppressed this insurgency, would not have tolerated such outfits just a few years ago. These days, life is more relaxed.

As darkness falls and there is still no sign of the bride, some friends and I decide to visit the center of Hakkari, the provincial capital. An armored personnel carrier, with a Turkish soldier in the turret peering over his machine gun, rumbles ominously through the city, which is swollen with unemployed Kurdish refugees from the countryside. But stalls in music stores overflow with CDs by Kurdish singers, including performers who were banned because Turkish authorities judged their music incendiary. Signs written in the once-taboo Kurdish language decorate shop windows.

By luck, we encounter Ihsan Colemerikli, a Kurdish intellectual whose book Hakkari in Mesopotamian Civilization is a highly regarded work of historical research. He invites us to his home, where we sip tea under an arbor. Colemerikli says there have been 28 Kurdish rebellions in the past 86 years—inspired by centuries of successful resistance to outsiders, invaders and would-be conquerors.

“Kurdish culture is a strong and mighty tree with deep roots,” he says. “Turks, Persians and Arabs have spent centuries trying to cut off this tree’s water so it would wither and die. But in the last 15 to 20 years there has been a new surge of water, so the tree is blossoming very richly.”

Back at the wedding party, the bride finally appears, wearing a brightly patterned, translucent veil and surrounded by attendants carrying candles. She is led slowly through the crowd to one of two armchairs in the center of the patio. Her husband sits in the other one. For half an hour they sit quietly and watch the party, then rise for their first dance, again surrounded by candles. I notice that the bride never smiles, and I ask if something is amiss. No, I’m told. It is customary for a Kurdish bride to appear somber as a way of showing how sad she is to leave her parents.

The party will go on until dawn, only to resume a few hours later. But as midnight approaches, my companions and I depart, our destination a corba salonu—a soup salon. In a few minutes we enter a brightly lit café. There are two soups on the menu. Lentil is my favorite, but when traveling I prefer the unfamiliar. The sheep’s head soup, made with meat scraped from inside the skull, is strong, lemony and assertive.

Isolation has long defined the Kurds, whose ancestral homeland is mountainous southeast Anatolia in what is now Turkey. Isolation helped them survive for thousands of years, while other peoples—Phrygians, Hittites, Lydians—faded from history’s pages. Sitting outdoors in a wooden chair, resplendent in a traditional ankle-length Kurdish gown, Semi Utan, 82, smiles wistfully as she recalls her childhood. “In my time we lived a completely natural life,” she says. “We had our animals. We made yogurt, milk and cheese. We produced our own honey. Herbs were used for healing the sick. No one ever went to a doctor. Everything was tied to nature.”

Today there are an estimated 25 million to 40 million Kurds, mostly Muslim, about half in Turkey and most of the others in Iran, Iraq and Syria. They are arguably the largest ethnic group in the world without an independent state of their own—a situation that, for many Kurds, is in painful contrast to their former glory and is a source of frustration and anger.

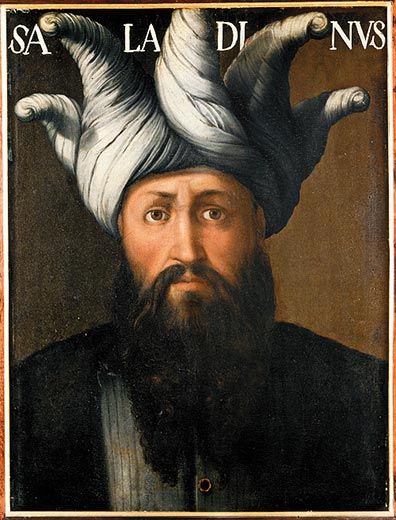

Kurdish tribes have lived in Anatolia since at least 1,000 B.C., twenty centuries before the first Turks arrived there. Ancient historians described them as a people not to be trifled with. Xenophon, the fourth-century B.C. Greek warrior and chronicler, wrote that they “lived in the mountains and were very warlike.” The peak of Kurdish power came in the 12th century, under their greatest leader, Salah-ad-Din (a.k.a. Saladin). While building a vast empire that included much of present-day Syria, Iraq and Egypt, Saladin recaptured many cities, including Jerusalem, that had been conquered by the crusaders. In Europe, he was held up as a model of chivalry.

But Saladin’s empire declined after his death, giving way to Ottoman and Persian power, which reached new heights in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Kurds rebelled and suffered terribly. Many were slaughtered. More were forcibly moved to outlying regions, including present-day Azerbaijan and Afghanistan, where rulers thought they would be less threatening.

As the Ottoman Empire collapsed after World War I, Anatolia’s Kurds saw a chance for nationhood. The Treaty of Sèvres, imposed on the defeated Turks in 1920, partitioned the territory of the Ottoman Empire among the victorious allied nations. It also gave Kurds the right to decide whether they wanted their own country. But under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal, later known as Ataturk, the Turks tore up the treaty. As Turkey’s first president, Ataturk saw the Kurds as a threat to his secular, modernizing revolution. His government forced thousands of them from their homes, closed Kurdish newspapers, banned Kurdish names and even restricted the use of the Kurdish language.

“The Kurds expected a sort of joint government, with the ability to control their own region, but that didn’t happen at all,” says Aliza Marcus, author of Blood and Belief: The PKK and the Kurdish Fight for Independence. “The state did everything it could to get rid of the Kurdish nation. By the late 1930s, Kurdish resistance was more or less crushed. But the Kurdish spirit was never wiped out.”

The most recent Kurdish revolt was set off by a group calling itself the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which grew out of Marxist student movements in the early 1970s. The Turkish state responded to PKK attacks in the 1980s with repressive measures that fanned the flames of rebellion. By 1990, southeastern Turkey was ablaze with war. Only after the PKK leader, Abdullah Ocalan, was captured in 1999 did the fighting recede. There was no formal peace accord, since the government refuses to deal with the PKK, which both Turkey and the United States consider a terrorist group. But from his prison cell, Ocalan called for a cease-fire. Not all PKK members and supporters have laid down their arms, and there are still occasional bombings and arson attacks. But most PKK militants are encamped across the border in the Qandil mountain region of northern Iraq—where they are protected by their Iraqi cousins, who have established a Kurdish republic in the north that enjoys broad autonomy. Kurds everywhere take pride that there is now a place where the Kurdish flag flies, official business is conducted in Kurdish and Kurdish-speaking professors teach Kurdish history in Kurdish universities. But many Turkish Kurds see the Kurdish regime in northern Iraq as corrupt, feudal and clan-based—not the modern democracy they wish for in Turkey.

“We are Turkish citizens,” Muzafer Usta tells me when I stop for pide—baked flatbread sprinkled with cheese, meat and chopped vegetables—at his café in Van, southeastern Turkey’s second-largest city. “We have no problem living with Turks. But we want to keep our culture. We were born as Kurds, and we also want to die as Kurds.”

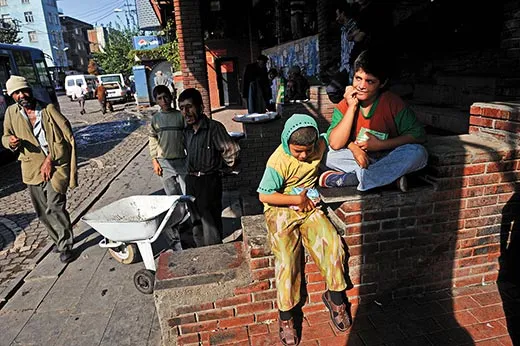

During the civil war of the 1990s, the Turkish Army—determined to deny sanctuary to guerrillas in the countryside—forcibly evacuated more than 2,000 villages, pushing up to three million Kurds from their homes. Many landed in large towns and, having little experience with urban life, melted into a new impoverished underclass. “This culture has been damaged very seriously by forced migration,” says Zozan Ozgokce, a 33-year-old financial consultant. “[Before], we never had beggars or street children or drug users.” The strains on families are apparent. In 2004, Ozgokce co-founded the Van Women’s Association, which conducted a survey of 776 Kurdish women in Van—82 percent said they were victims of domestic abuse “often” or “very often.”

“Our society has been seriously injured, no doubt,” says Azize Leygara, 32, who runs Children Under the Same Roof, a nonprofit group that seeks to rescue Kurdish street kids in Diyarbakir, some 230 miles west of Van. “Our challenge is not to go back to life as it was. That’s gone, and it won’t be back. Our challenge now is to create a new social structure.”

The Umut Bookstore (the name means “hope”) in the dusty Turkish town of Semdinli is set amid jagged peaks 40 miles from the Iraqi border. The bookseller, Seferi Yilmaz, 47, became a local hero the hard way—by surviving a 2006 bomb attack on his store. Witnesses chased the assailant and surrounded the car in which his two collaborators were waiting. All three men turned out to be tied to the Turkish security forces; two were noncommissioned gendarmerie officers and the third was a former PKK guerrilla who had become a government informer. They were apparently trying to kill Yilmaz, who had served a prison term after being convicted of PKK membership in the 1980s. The incident set off waves of outrage among Kurds and provoked further demands for reform.

Inside the bookstore, Yilmaz showed me four glass cases holding artifacts from the attack, including bloodstained books and a teapot peppered with shrapnel holes. One man was killed in the bombing and eight others were injured.

“If you don’t accept the existence of a culture or an ethnicity, of course it cannot be permitted to have music or art or literature,” he said. “The Turks don’t recognize our identity, so they don’t recognize our culture. That’s why our culture is so politicized. Just to say that this culture exists is taken as a political act.”

Still, everyone I met—even the most outspoken Kurdish nationalists—told me they wanted their homeland to remain part of Turkey. Traveling across the country, it’s easy to understand why. Turkey is by most standards the most democratic Muslim country—a powerful, modern society with a vibrant economy and extensive ties to the international community. If the mainly Kurdish provinces of the southeast were to become independent, their state would be landlocked and weak in a highly volatile region—a tempting target for powers such as Iran, Iraq or Syria. “We don’t want an independence that would change borders,” says Gulcihan Simsek, mayor of a sprawling, impoverished borough of Van called Bostanici. “Absolute independence is not a requirement today. We want true regional autonomy, to make our own decisions and use our own natural resources, but always within the Turkish nation and under the Turkish flag.”

In Istanbul, I asked Turkish President Abdullah Gul why the Turkish state has been unable, over the course of its nearly 90-year history, to find peace with its Kurdish citizens, and what chance there is for it now.

“Some call it terror, some call it the southeast problem, some call it the Kurdish problem,” he responds. “The problem was this: the lack of democracy, the standard of democracy....When we upgrade that standard, all these problems will find solutions.” In practical terms, that means stronger legal protections for all citizens against discrimination, whether based on gender, religious belief or ethnicity.

That process is already beginning. Since my conversation with President Gul, the government has licensed a Kurdish television channel and allowed a university in Mardin, a historic town near the Syrian border, to open a center for the study of Kurdish language and literature. Steps like these would have been unthinkable only a few years ago, and government leaders say there will soon be more like them.

The European Union (EU) has made it clear that a key obstacle to Turkish membership is the continuing “Kurdish problem.” Turks have good reason to want to join. The EU requires member states to implement free elections, prudent economic policies and civilian control of the military—making membership as close to a guarantee of permanent stability and prosperity as the modern world can offer. And Turkish acceptance as part of Europe would be a powerful example of how Islam and democracy can blend peacefully.

“If we solve this one problem, Turkey can become the pearl of this region,” says Soli Ozel, a professor of political science at Istanbul Bilgi University. “There would be almost nothing we couldn’t be or do. People in power are starting to grasp this reality.”

Although Kurdish culture has traditionally been defined by its isolation, the young people I met seem determined to change that. They are proud of their Kurdish identity but refuse to be confined by it. They want to be the first globalized Kurds.

Current trends in Kurdish music reflect that impulse. Like many nomadic peoples, the Kurds developed a strong folk music tradition they use to pass down their stories from one generation to the next. They sang songs about love, separation and historical events, accompanied by such instruments as the def (a bass drum) and the zirne (a kind of oboe). Young Kurds today favor rock-oriented bands like Ferec, which was setting up at a restaurant I visited in Hakkari. Ferec is an evocative Ottoman-era Turkish word variously translated as liberation, emancipation, overcoming adversity and coming to a positive state of mind.

“Ten years ago it was not easy to do what we do,” said the band leader (who asked that I not use his name because “we’re a group and don’t want to be seen as individuals”). “Now it’s better. But our more extreme political songs—we still can’t play them....Some boys in our society are eager to fight. They want to be set on fire. We’re careful with them. We don’t want to do this.”

Young Kurdish writers, too, want to bring the long tradition of storytelling into the modern age. In 2004, Lal Lalesh, a 29-year-old poet from Diyarbakir, founded a publishing house that specializes in Kurdish literature. He has commissioned translations of foreign works such as A Midsummer Night’s Dream and has issued more than a dozen out-of-print Kurdish classics. His main purpose, though, is to publish new writing.

“Before, our writers concentrated mainly on Kurdish subjects,” Lalesh says. “In the last few years, they’ve started to deal with other themes, like sex, individuality, the social aspects of life. Some are even writing crime novels. For the first time, Kurds are breaking out of their isolation in their own society, and also breaking barriers that were imposed by the political system.”

Another group is turning to cinema. More than a dozen have graduated from film school and gathered together at the nascent Diyarbakir Arts Center. In the past two years they have produced nearly 20 short films.

“Most of our artists have broken out of the nationalist shell and gone beyond being from one group or loving one nation,” says Ozlem Orcen, 28, who works at the center. “Twenty years from now, I could imagine some of them reaching a high level, an international level.”

And yet, there is still “a great sense of belonging to the Kurdish nation,” says Henri Barkey, a professor of international relations at Pennsylvania’s Lehigh University and co-author of Turkey’s Kurdish Question. “In a way, globalization has enhanced the sense of identity among Kurds. It’s the same phenomenon you see in Europe, where even small populations are feeling drawn to their primordial identity.”

One expression of that identity is a return to nomadic life. Kurds who were forbidden during the civil war to live as nomads may now do so again. I visited one such group, made up of 13 families, at a remote mountainside encampment several hours from Hakkari. The route took me over rugged hills, along the rims of vertiginous gorges, and past the haunting ruins of a church, destroyed in the convulsions that accompanied the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century.

Soon after arriving at the camp, I was invited into a large, airy yurt for lunch. Sitting on a carpet and leaning against soft cushions, I feasted on fresh yogurt, honey, piping-hot flatbread and four kinds of cheese.

These nomads move through the hills for about half the year, then return to lowlands in winter. They tend a herd of more than 1,000 sheep and goats. Twice a day, the entire herd is brought to the camp and eased through a funnel-shaped, chicken-wire enclosure, at the end of which women on stools wait to milk them. They work with amazing dexterity, taking barely an hour to finish the entire job. The milk will be made into cheese, which the nomads sell to wholesalers for delivery to grocery stores across the region.

The elected leader of this group is a thoughtful, taciturn man named Salih Tekce. Standing outside his yurt, framed by the wild mountains Kurds have always loved, he tells me that his village was burned and that he had to move to town, scraping by as a taxi driver for 12 years.

“It was terrible,” he said. “I hated it. I felt like I was carrying each passenger on my shoulders.”

Like the bookstore owner, the band members, the local politicians and most others here, Tekce believes Kurdish resistance is best achieved not by force of arms, but by renewal. “Through it all, we love life,” he tells me. “We don’t feel defeated. We know how to die, but we also know how to live.”

Former New York Times correspondent Stephen Kinzer wrote about Iran in the October 2008 issue of Smithsonian. Photographer Lynsey Addario is based in New Delhi.