Twenty-five years ago, I was drawn to Somalia in the aftermath of Operation Restore Hope, a U.S. initiative supporting a United Nations resolution that aimed to halt widespread starvation. The effort, started in 1992, secured trade routes so food could get to Somalis. The U.N. estimated that no fewer than 250,000 lives were saved. But Operation Restore Hope would be best remembered in the United States for a spectacular debacle that has shaped foreign policy ever since.

Almost right away, militias led by the Somali warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid began attacking and killing U.N. peacekeepers. On October 3 and 4, 1993, U.S. forces set out on a snatch-and-grab mission to arrest two of Aidid’s lieutenants. The plan was to surround a white three-story house in the capital city of Mogadishu where leaders of Aidid’s Habar Gidir clan were gathering. Rangers would helicopter in, lower themselves on ropes and surround the building on all sides. A ground convoy of trucks and Humvees would wait outside the gate to carry away the troops and their prisoners. Altogether, the operation would involve 19 aircraft, 12 vehicles and around 160 troops.

The operation didn’t go as planned. The ground convoy ran up against barricades formed by local militias. One helicopter landed a block north of its target and couldn’t move closer because of groundfire. A ranger fell from his rope and had to be evacuated. Insurgents shot down two American Black Hawk helicopters with rocket-propelled grenades. When about 90 U.S. Rangers and Delta Force operators rushed to the rescue, they were caught in an intense exchange of gunfire and trapped overnight.

Altogether, the 18-hour urban firefight, later known as the Battle of Mogadishu, left 18 Americans and hundreds of Somalis dead. News outlets broadcast searing images of jubilant mobs dragging the bodies of dead Army special operators and helicopter crewmen through the streets of Mogadishu. The newly elected U.S. president, Bill Clinton, halted the mission and ordered the Special Forces out by March 31, 1994.

For Somalis, the consequences were severe. Civil war raged—Aidid himself was killed in the fighting in 1996—and the country remained lawless for decades. Pirate gangs along the country’s long Indian Ocean coastline menaced vital shipping lanes. Wealthy and educated Somalis fled.

When I visited Somalia for the first time, in 1997, the country was well off the map of world interest. There were no commercial flights to the capital city, but each morning small planes took off from Wilson Airport in Nairobi, Kenya, for rural landing strips throughout the country. My plane was met by a small platoon of hired gunmen. On our way into the city, smaller bands of brigands grudgingly removed barriers that had been stretched across the dirt road to halt traffic. The driver of my vehicle tossed fistfuls of near-worthless paper Somali shillings as we passed these local versions of tollbooths.

The city itself was in ruins. The few large buildings were battle-scarred and filled with squatters, whose fires glowed through windows empty of glass and stripped of aluminum frames. Gas generators banged away to provide power to those few places where people could afford it. Militias fought along the borders of city sectors, filling the hospitals with bloody fighters, most of them teenagers. The streets were mostly empty, except for caravans of gunmen. Without government, laws, schools, trash pickups or any feature of civil society, extended clans offered the only semblance of safety or order. Most were at war with each other for scarce resources.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b5/05/b5058707-3949-4403-b1bf-33f18893e5ab/janfeb2019_f01_blackhawk.jpg)

I described this wasteland in my 1999 book about the Battle of Mogadishu and its aftermath, Black Hawk Down (the basis of the 2001 movie directed by Ridley Scott). When I returned to the States and spoke to college audiences about the state of things in Somalia, I would ask if there were any anarchists in the crowd. Usually a hand or two went up. “Good news,” I told them, “you don’t have to wait.”

The consequences were felt in America, too. After Mogadishu, the United States became wary of deploying ground forces anywhere. So there was no help from America in 1994 when Rwandan Hutus slaughtered as many as a million of their Tutsi countrymen. Despite a global outcry, U.S. forces stayed home in 1995 as Bosnian Serbs mounted a genocidal campaign against Muslim and Croatian civilians.

That isolationism ended abruptly on September 11, 2001. But even as Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama sent troops to Iraq and Afghanistan, they kept their distance from the Islamic insurgents in Somalia. During the last two years of the Obama administration, there were only 18 airstrikes (both drones and manned) on Somalia.

Now things are changing. In the past two years, U.S. forces have conducted 63 airstrikes on targets in Somalia. The number of American forces on the ground has doubled, to about 500. And there have already been fatalities: a Navy SEAL, Senior Chief Special Warfare Operator Kyle Milliken, was killed in May of 2017 assisting Somali National Army troops in a raid about 40 miles west of Mogadishu, and Army Staff Sgt. Alexander Conrad was killed and four others wounded in June of this year during a joint mission in Jubaland.

All of this might raise the question: What do we expect to achieve by returning to Somalia? After years of turmoil in Afghanistan and Iraq, why should we expect this mission to be any different?

* * *

A casual visitor to Mogadishu today might not see an urgent need for U.S. ground troops. There are tall new buildings, and most of the old shanties have been replaced by houses. There are police, sanitation crews and new construction everywhere. Peaceful streets and thriving markets have begun to restore the city to its former glory as a seaside resort and port. Somali expatriates have begun reinvesting, and some are returning. The airport is up and running, with regular Turkish Airlines flights.

Brig. Gen. Miguel Castellanos first entered Mogadishu as a young Army officer with the Tenth Mountain Division in 1992, looking down from the open door of a Black Hawk helicopter. He is now the senior U.S. military officer in Somalia. “I was pretty surprised when I landed a year ago and there was actually a skyline,” he told me.

Somalia largely has its neighbors to thank for this prosperity. In 2007, African Union soldiers—mostly from Uganda but also from Kenya, Ethiopia, Burundi, Djibouti and Sierra Leone—began pushing the extremist group the Shabab out of the country’s urban centers with an effort dubbed the African Union Mission to Somalia (AMISOM). The United States lent support in the form of training and equipment. Turkey and the United Arab Emirates have taken advantage of the newfound peace and bankrolled development of Somalia’s port cities.

The problem is in the rural areas. There, basic security depends almost entirely on local militias whose loyalties are tied to clans and warlords. “There is a real black-and-white, good and evil struggle in Somalia,” said Stephen Schwartz, who served as U.S. ambassador there until the end of September 2017. “The forces of chaos, of Islamist extremism, are powerful and have decades of inertia behind them in criminality, the warlords and cartels.”

If current conditions persist, the Shabab, Al Qaeda’s affiliate in East Africa, could end up controlling large parts of the country, says Abdullahi Halakhe, a security consultant for the Horn of Africa who previously worked for the U.N. and the BBC. “They would be running their own schools, their own clinics, collecting trash. That is where the appeal of this group comes.”

So far, the United States has been dealing with this threat with a string of targeted killings. Top Shabab leaders were killed by U.S. raids and airstrikes in 2017 and 2018. But the experts I spoke with told me these hits may not ultimately accomplish much. “Killing leaders is fine, makes everybody feel good; they wake up in the morning, big headline they can quantify—‘Oh we killed this guy, we killed that guy’—but it has absolutely no long-term effect and it really doesn’t have any short-term effect either,” said Brig. Gen. Don Bolduc, who until last year commanded Special Operations in Africa and directly oversaw such efforts. “Someone is always going to be there to be the next leader.”

Every expert I spoke with recommended investing in rebuilding the country instead. This approach didn’t work well in Afghanistan, but there are differences. Somalia’s president, Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, is friendly to the United States—and he was chosen by his own people, not installed by the U.S. Somalia’s Islamist extremists no longer enjoy broad ideological support. “There was a time when the Shabab could transcend all the regional clan differences and project this kind of Pan Somalia, Pan Islam type of image,” said Halakhe. “That is gone.”

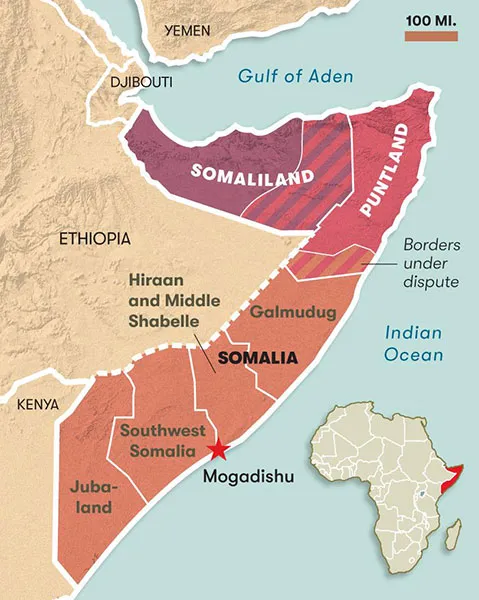

The country’s problems are mostly economic, says Bolduc, and solving them would cost so much less than the trillions spent in Afghanistan and Iraq that the question doesn’t fall into the same category. He points to success in Puntland, Somalia’s northernmost member state. In 2017, Bolduc and his special forces worked with the state’s president, Abdiweli Mohamed Ali Gaas, and with American diplomats to assemble local forces and tribal elders. They trained the Puntland militias but offered no air or ground support. Working entirely on their own, Somali forces moved from southern Puntland up to a northern port where the Islamic State (a rival of the Shabab) had established control. They took back everything and secured it in about a week. “ISIS East Africa has not been able to get a foothold back into these areas,” says Bolduc. “And those villages are holding today.”

Schwartz says this success could be replicated throughout Somalia if the United States invested a fraction of what it has been spending on special operators and drones. “The budget of the Somali government is comparable to the salary cap for the Washington Nationals baseball team,” he said. “They’re both around $210 million.” He said that less than half that amount would be enough to enable the president to pay the salaries of Somalia National Army recruits and other government employees. That step alone, he says, “would make our investment on the military side more successful.”

It would be foolish to try such an intervention in other countries where America is in conflicts. It wouldn’t work, for instance, in Pakistan, where there’s a powerful Islamist presence, a sophisticated military and a history of tensions with the United States. Our experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq—and, years ago, in Vietnam—showed us that American efforts will continually fail if there isn’t a willing local government with the support of the people.

But just because those approaches failed in the past doesn’t mean they have to fail in Somalia. Radical Islam takes different forms, and there can be no one-size-fits-all approach to fighting it. In countries where leaders are friendly and ideologies don’t run deep, there may still be an opportunity to build enduring stability. These days, that might be as good a definition of “victory” as we can get.

Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War

On October 3, 1993, about a hundred elite U.S. soldiers were dropped by helicopter into the teeming market in the heart of Mogadishu, Somalia. Their mission was to abduct two top lieutenants of a Somali warlord and return to base. It was supposed to take an hour. Instead, they found themselves pinned down through a long and terrible night fighting against thousands of heavily armed Somalis.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/b7/42b7648e-4522-42a0-bbbc-3990d51e4ca9/mogo_121.jpg)