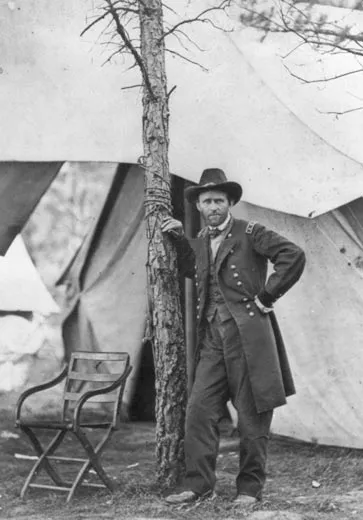

Lincoln as Commander in Chief

A self-taught strategist with no combat experience, Abraham Lincoln saw the path to victory more clearly than his generals

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Lincoln-McClellan-Antietam-631.jpg)

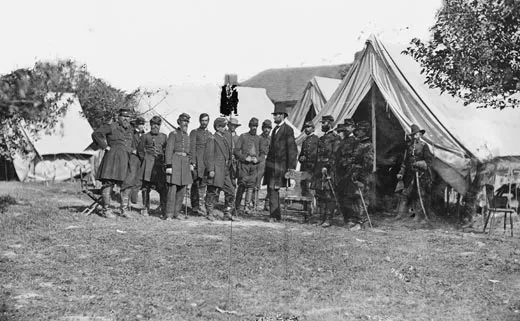

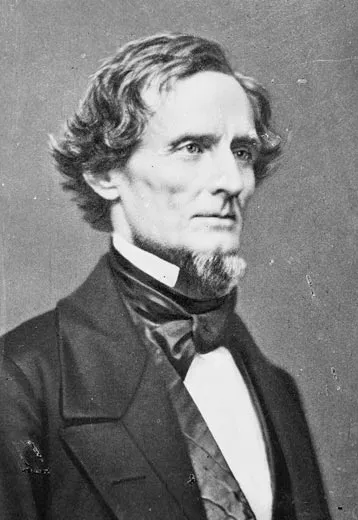

When the American Civil War began, president Abraham Lincoln was far less prepared for the task of commander in chief than his Southern adversary. Jefferson Davis had graduated from West Point (in the lowest third of his class, to be sure), commanded a regiment that fought intrepidly at Buena Vista in the Mexican War and served as secretary of war in the Franklin Pierce administration from 1853 to 1857. Lincoln's only military experience had come in 1832, when he was captain of a militia unit that saw no action in the Black Hawk War, which began when Sac and Fox Indians (led by the war chief Black Hawk) tried to return from Iowa to their ancestral homeland in Illinois in alleged violation of a treaty of removal they had signed. During Lincoln's one term in Congress, he mocked his military career in an 1848 speech. "Did you know I am a military hero?" he said. "I fought, bled and came away" after "charges upon the wild onions" and "a good many bloody struggles with the Musquetoes."

When he called state militia into federal service on April 15, 1861—following the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter—Lincoln therefore faced a steep learning curve as commander in chief. He was a quick study, however; his experience as a largely self-taught lawyer with a keen analytical mind who had mastered Euclidean geometry for mental exercise enabled him to learn quickly on the job. He read and absorbed works on military history and strategy; he observed the successes and failures of his own and the enemy's military commanders and drew apt conclusions; he made mistakes and learned from them; he applied his large quotient of common sense to slice through the obfuscations and excuses of military subordinates. By 1862 his grasp of strategy and operations was firm enough almost to justify the overstated but not entirely wrong conclusion of historian T. Harry Williams: "Lincoln stands out as a great war president, probably the greatest in our history, and a great natural strategist, a better one than any of his generals."

As president of the nation and leader of his party as well as commander in chief, Lincoln was principally responsible for shaping and defining national policy. From first to last, that policy was the preservation of the United States as one nation, indivisible, and as a republic based on majority rule. Although Lincoln never read Karl von Clausewitz's famous treatise On War, his actions were a consummate expression of Clausewitz's central argument: "The political objective is the goal, war is the means of reaching it, and means can never be considered in isolation from their purpose. Therefore, it is clear that war should never be thought of as something autonomous but always as an instrument of policy."

Some professional military commanders tended to think of war as "something autonomous" and deplored the intrusion of political considerations into military matters. Take the notable example of "political generals." Lincoln appointed many prominent politicians with little or no military training or experience to the rank of brigadier or major general. Some of them received these appointments so early in the war that they subsequently outranked professional, West Point–educated officers. Lincoln also commissioned important ethnic leaders as generals with little regard to their military merits.

Historians who deplore the abundance of political generals sometimes cite an anecdote to mock the process. One day in 1862, the story goes, Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton were going over a list of colonels for promotion to brigadier general. Coming to the name of Alexander Schimmelfennig, the president said that "there has got to be something done unquestionably in the interest of the Dutch, and to that end I want Schimmelfennig appointed." Stanton protested that there were better-qualified German-Americans. "No matter about that," Lincoln supposedly said, "his name will make up for any difference there may be."

General Schimmelfennig is remembered today mainly for hiding for three days in a woodshed next to a pigpen to escape capture at Gettysburg. Other political generals are also remembered more for their military defeats or blunders than for any positive achievements. Often forgotten are the excellent military records of some political generals like John A. Logan and Francis P. Blair (among others). And some West Pointers, notably Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman, might have languished in obscurity had it not been for the initial sponsorship of Grant by Congressman Elihu B. Washburne and of Sherman by his brother John, a U.S. senator.

Even if all political generals, or generals in whose appointments politics played a part, turned out to have mediocre military records, however, the process would have had a positive impact on national strategy by mobilizing their constituencies for the war effort. On the eve of the war, the U.S. Army consisted of approximately 16,400 men, of whom about 1,100 were commissioned officers. Of these, some 25 percent resigned to join the Confederate army. By April 1862, when the war was a year old, the volunteer Union army had grown to 637,000 men. This mass mobilization could not have taken place without an enormous effort by local and state politicians as well as by prominent ethnic leaders.

Another important issue that began as a question of national strategy eventually crossed the boundary to become policy as well. That was the issue of slavery and emancipation. During the war's first year, one of Lincoln's top priorities was to keep border state Unionists and Northern antiabolitionist Democrats in his war coalition. He feared, with good reason, that the balance in three border slave states might tip to the Confederacy if his administration stepped prematurely toward emancipation. When Gen. John C. Frémont issued a military order freeing the slaves of Confederate supporters in Missouri, Lincoln revoked it in order to quell an outcry from the border states and Northern Democrats. To sustain Frémont's order, Lincoln believed, "would alarm our Southern Union friends, and turn them against us—perhaps ruin our rather fair prospect for Kentucky....I think that to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we can not hold Missouri, nor as I think, Maryland. These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capitol."

During the next nine months, however, the thrust of national strategy shifted away from conciliating the border states and anti-emancipation Democrats. The antislavery Republican constituency grew louder and more demanding. The argument that slavery had brought on the war and that reunion with slavery would only sow the seeds of another war became more insistent. The evidence that slave labor sustained the Confederate economy and the logistics of Confederate armies grew stronger. Counteroffensives by Southern armies in the summer of 1862 wiped out many of the Union gains of the winter and spring. Many northerners, including Lincoln, became convinced that bolder steps were necessary. To win the war over an enemy fighting for and sustained by slavery, the North must strike at slavery.

In July 1862, Lincoln decided on a major change in national strategy. Instead of deferring to the border states and Northern Democrats, he would activate the Northern antislavery majority that had elected him and mobilize the potential of black manpower by issuing a proclamation of freedom for slaves in rebellious states—the Emancipation Proclamation. "Decisive and extreme measures must be adopted," Lincoln told members of his cabinet, according to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. Emancipation was "a military necessity, absolutely necessary to the preservation of the Union. We must free the slaves or be ourselves subdued."

By trying to convert a Confederate resource to Union advantage, emancipation thus became a crucial part of the North's national strategy. But the idea of putting arms in the hands of black men provoked even greater hostility among Democrats and border state Unionists than emancipation itself. In August 1862, Lincoln told delegates from Indiana who offered to raise two black regiments that "the nation could not afford to lose Kentucky at this crisis" and that "to arm the negroes would turn 50,000 bayonets from the loyal border States against us that were for us."

Three weeks later, however, the president quietly authorized the War Department to begin organizing black regiments on the South Carolina Sea Islands. And by March 1863, Lincoln had told his military governor of occupied Tennessee that "the colored population is the great available and yet unavailed of, force for restoring the Union. The bare sight of fifty thousand armed, and drilled black soldiers on the banks of the Mississippi, would end the rebellion at once. And who doubts that we can present that sight, if we but take hold in earnest."

This prediction proved overoptimistic. But in August 1863, after black regiments had proved their worth at Fort Wagner and elsewhere, Lincoln told opponents of their employment that in the future "there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget that, with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they have strove to hinder it."

Lincoln also took a more active, hands-on part in shaping military strategy than presidents have done in most other wars. This was not necessarily by choice. Lincoln's lack of military training inclined him at first to defer to General in Chief Winfield Scott, America's most celebrated soldier since George Washington. But Scott's age (75 in 1861), poor health and lack of energy placed a greater burden on the president. Lincoln was also disillusioned by Scott's March 1861 advice to yield both Forts Sumter and Pickens. Scott's successor, Gen. George B. McClellan, proved an even greater disappointment to Lincoln.

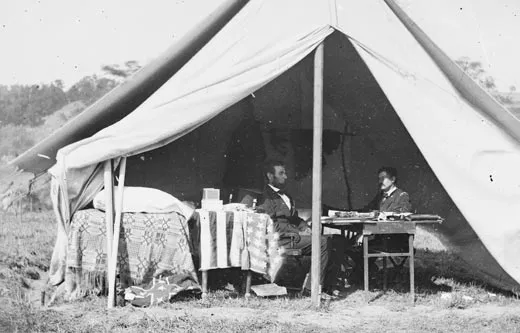

In early December 1861, after McClellan had been commander of the Army of the Potomac for more than four months and had done little with it except conduct drills and reviews, Lincoln drew on his reading and discussions of military strategy to propose a campaign against Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's army, then occupying the Manassas-Centreville sector 25 miles from Washington. Under Lincoln's plan, part of the Army of the Potomac would feign a frontal attack while the rest would use the Occoquan Valley to move up on the flank and rear of the enemy, cut its rail communications and catch it in a pincer movement.

It was a good plan; indeed it was precisely what Johnston most feared. McClellan rejected it in favor of a deeper flanking movement all the way south to Urbana on the Rappahannock River. Lincoln posed a series of questions to McClellan, asking him why his distant-flanking strategy was better than Lincoln's short-flanking plan. Three sound premises underlay Lincoln's questions: first, the enemy army, not Richmond, should be the objective; second, Lincoln's plan would enable the Army of the Potomac to operate near its own base (Alexandria) while McClellan's plan, even if successful, would draw the enemy back toward his base (Richmond) and lengthen the Union supply line; and third, "does not your plan involve a greatly larger expenditure of time...than mine?"

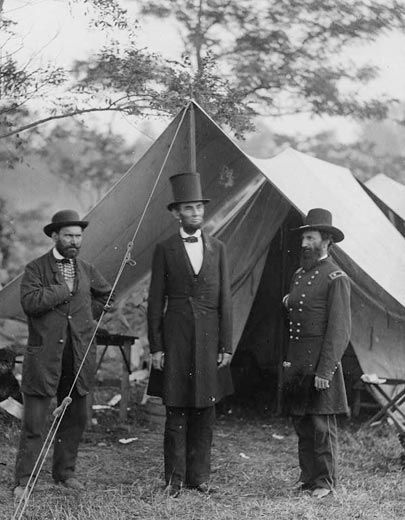

McClellan brushed off Lincoln's questions and proceeded with his own plan, bolstered by an 8–4 vote of his division commanders in favor of it, which caused Lincoln reluctantly to acquiesce. Johnston then threw a monkey wrench into McClellan's Urbana strategy by withdrawing from Manassas to the south bank of the Rappahannock—in large part to escape the kind of maneuver Lincoln had proposed. McClellan now shifted his campaign all the way to the Virginia peninsula between the York and James rivers. Instead of attacking a line held by fewer than 17,000 Confederates near Yorktown with his own army, then numbering 70,000, McClellan, in early April, settled down for a siege that would give Johnston time to bring his whole army down to the peninsula. An exasperated Lincoln telegraphed McClellan on April 6: "I think you better break the enemies' line from York-town to Warwick River, at once. They will probably use time, as advantageously as you can." McClellan's only response was to comment petulantly in a letter to his wife that "I was much tempted to reply that he had better come & do it himself."

In an April 9 letter to the general, Lincoln enunciated another major theme of his military strategy: the war could be won only by fighting the enemy rather than by endless maneuvers and sieges to occupy places. "Once more," wrote Lincoln, "let me tell you, it is indispensable to you that you strike a blow. You will do me the justice to remember I always insisted, that going down the Bay in search of a field, instead of fighting at or near Manassas, was only shifting, and not surmounting, a difficulty—that we would find the same, or equal intrenchments, at either place. The country will not fail to note—is now noting—that the present hesitation to move upon an intrenched enemy, is but the story of Manassas repeated."

But the general who acquired the nickname of Tardy George never learned that lesson. The same was true of several other generals who did not live up to Lincoln's expectations. They seemed to be paralyzed by responsibility for the lives of their men as well as the fate of their army and nation. This intimidating responsibility made them risk-averse. This behavior especially characterized commanders of the Army of the Potomac, who operated in the glare of media publicity with the government in Washington looking over their shoulders. In contrast, officers like Ulysses S. Grant, George H. Thomas and Philip H. Sheridan got their start in the western theater hundreds of miles distant, where they worked their way up from command of a regiment step by step to larger responsibilities away from media attention. They were able to grow into these responsibilities and to learn the necessity of taking risks without the fear of failure that paralyzed McClellan.

Meanwhile, Lincoln's frustration with the lack of activity in the Kentucky-Tennessee theater had elicited from him an important strategic concept. Generals Henry W. Halleck and Don C. Buell commanded in the two western theaters separated by the Cumberland River. Lincoln urged them to cooperate in a joint campaign against the Confederate army defending a line from eastern Kentucky to the Mississippi River. Both responded in early January 1862 that they were not yet ready. "To operate on exterior lines against an enemy occupying a central position will fail," wrote Halleck. "It is condemned by every military authority I have ever read." Halleck's reference to "exterior lines" described the conundrum of an invading or attacking army operating against an enemy that holds a defensive perimeter resembling a semi-circle—the enemy enjoys the advantage of "interior lines" that enables it to shift reinforcements from one place to another within that arc.

By this time Lincoln had read some of those authorities (including Halleck) and was prepared to challenge the general's reasoning. "I state my general idea of the war," he wrote to both Halleck and Buell, "that we have the greater numbers, and the enemy has the greater facility of concentrating forces upon points of collision; that we must fail, unless we can find some way to making our advantage an over-match for his; and that this can be only done by menacing him with superior forces at different points, at the same time; so that we can safely attack, one, or both, if he makes no change; and if he weakens one to strengthen the other, forbear to attack the strengthened one, but seize and hold the weakened one, gaining so much."

Lincoln clearly expressed here what military theorists define as "concentration in time" to counter the Confederacy's advantage of interior lines that enabled Southern forces to concentrate in space. The geography of the war required the North to operate generally on exterior lines while the Confederacy could use interior lines to shift troops to the point of danger. By advancing on two or more fronts simultaneously, Union forces could neutralize this advantage, as Lincoln understood but Halleck and Buell seemed unable to grasp.

Not until Grant became general in chief in 1864 did Lincoln have a commander in place who would carry out this strategy. Grant's policy of attacking the enemy wherever he found it also embraced Lincoln's strategy of trying to cripple the enemy as far from Richmond (or any other base) as possible rather than maneuvering to occupy or capture places. From February to June 1862, Union forces had enjoyed remarkable success in capturing Confederate territory and cities along the south Atlantic coast and in Tennessee and the lower Mississippi Valley, including the cities of Nashville, New Orleans and Memphis. But Confederate counteroffensives in the summer recaptured much of this territory (though not these cities). Clearly, the conquest and occupation of places would not win the war so long as enemy armies remained capable of reconquering them.

Lincoln viewed these Confederate offensives more as an opportunity than a threat. When the Army of Northern Virginia began to move north in the campaign that led to Gettysburg, Gen. Joseph Hooker proposed to cut in behind the advancing Confederate forces and attack Richmond. Lincoln rejected the idea. "Lee's Army, and not Richmond, is your true objective point," he wired Hooker on June 10, 1863. "If he comes toward the Upper Potomac, follow on his flank, and on the inside track, shortening your [supply] lines, whilst he lengthens his. Fight him when opportunity offers." A week later, as the enemy was entering Pennsylvania, Lincoln told Hooker that this invasion "gives you back the chance that I thought McClellan lost last fall" to cripple Lee's army far from its base. But Hooker, like McClellan, complained (falsely) that the enemy outnumbered him and failed to attack while Lee's army was strung out for many miles on the march.

Hooker's complaints compelled Lincoln to replace him on June 28 with George Gordon Meade, who punished but did not destroy Lee at Gettysburg. When the rising Potomac trapped Lee in Maryland, Lincoln urged Meade to close in for the kill. If Meade could "complete his work, so gloriously prosecuted thus far," said Lincoln, "by the literal or substantial destruction of Lee's army, the rebellion will be over."

Instead, Meade pursued the retreating Confederates slowly and tentatively, and failed to attack them before they managed to retreat safely over the Potomac on the night of July 13-14. Lincoln had been distressed by Meade's congratulatory order to his army on July 4, which closed with the words that the country now "looks to the army for greater efforts to drive from our soil every vestige of the presence of the invader." "Great God!" cried Lincoln. "This is a dreadful reminiscence of McClellan," who had proclaimed a great victory when the enemy retreated across the river after Antietam. "Will our Generals never get that idea out of their heads? The whole country is our soil." That, after all, was the point of the war.

When word came that Lee had escaped, Lincoln was both angry and depressed. He wrote to Meade: "My dear general, I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee's escape....Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it."

Having gotten these feelings off his chest, Lincoln filed the letter away unsent. But he never changed his mind. And two months later, when the Army of the Potomac was maneuvering and skirmishing again over the devastated land between Washington and Richmond, the president declared that "to attempt to fight the enemy back to his intrenchments in Richmond...is an idea I have been trying to repudiate for quite a year."

Five times in the war Lincoln tried to get his field commanders to trap enemy armies that were raiding or invading northward by cutting in south of them and blocking their routes of retreat: during Stonewall Jackson's drive north through the Shenandoah Valley in May 1862; Lee's invasion of Maryland in September 1862; Braxton Bragg's and Edmund Kirby Smith's invasions of Kentucky in the same month; Lee's invasion of Pennsylvania in the Gettysburg campaign; and Jubal Early's raid to the outskirts of Washington in July 1864. Each time his generals failed him, and in most cases they soon found themselves relieved of command.

In all of these instances the slowness of Union armies trying to intercept or pursue the enemy played a key part in their failures. Lincoln expressed repeated frustration with the inability of his armies to march as light and fast as Confederate armies. Much better supplied than the enemy, Union forces were actually slowed down by the abundance of their logistics. Most Union commanders never learned the lesson pronounced by Confederate Gen. Richard Ewell that "the road to glory cannot be followed with much baggage."

Lincoln's efforts to get his commanders to move faster with fewer supplies brought him into active participation at the operational level of his armies. In May 1862 he directed General Irvin McDowell to "put all possible energy and speed into the effort" to trap Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley. Lincoln probably did not fully appreciate the logistical difficulties of moving large bodies of troops, especially in enemy territory. On the other hand, the president did comprehend the reality expressed by the Army of the Potomac's quartermaster in response to McClellan's incessant requests for more supplies before he could advance after Antietam, that "an army will never move if it waits until all the different commanders report that they are ready and want no more supplies." Lincoln told another general in November 1862 that "this expanding, and piling up of impedimenta, has been, so far, almost our ruin, and will be our final ruin if it is not abandoned....You would be better off.... for not having a thousand wagons, doing nothing but hauling forage to feed the animals that draw them, and taking at least two thousand men to care for the wagons and animals, who otherwise might be two thousand good soldiers."

With Grant and Sherman, Lincoln finally had top generals who followed Ewell's dictum about the road to glory and who were willing to demand of their soldiers—and of themselves—the same exertions and sacrifices that Confederate commanders required of theirs. After the 1863 Vicksburg campaign that captured a key stronghold in Mississippi, Lincoln said of General Grant—whose rapid mobility and absence of a cumbersome supply line were a key to its success—that "Grant is my man and I am his the rest of the war!"

Lincoln had opinions about battlefield tactics, but he rarely made suggestions to his field commanders for that level of operations. One exception, however, occurred in the second week of May 1862. Upset by McClellan's monthlong siege of Yorktown without any apparent result, Lincoln and Secretary of War Stanton and Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase sailed down to Hampton Roads on May 5 to discover that the Confederates had evacuated Yorktown before McClellan could open with his siege artillery.

Norfolk remained in enemy hands, however, and the feared CSS Virginia (formerly the Merrimack) was still docked there. On May 7, Lincoln took direct operational control of a drive to capture Norfolk and to push a gunboat fleet up the James River. The president ordered Gen. John Wool, commander at Fort Monroe, to land troops on the south bank of Hampton Roads. Lincoln even personally carried out a reconnaissance to select the best landing place. On May 9, the Confederates evacuated Norfolk before Northern soldiers could get there. Two days later the Virginia's crew blew her up to prevent her capture. Chase rarely found opportunities to praise Lincoln, but on this occasion he wrote to his daughter: "So has ended a brilliant week's campaign of the President; for I think it quite certain that if he had not come down, Norfolk would still have been in possession of the enemy, and the 'Merrimac' as grim and defiant and as much a terror as ever....The whole coast is now virtually ours."

Chase exaggerated, for the Confederates would have had to abandon Norfolk to avoid being cut off when Johnston's army retreated up the north side of the James River. But Chase's words can perhaps be applied to Lincoln's performance as commander in chief in the war as a whole. He enunciated a clear national policy, and through trial and error evolved national and military strategies to achieve it. The nation did not perish from the earth but experienced a new birth of freedom.

Reprint from Our Lincoln: New Perspectives on Lincoln and His World, edited by Eric. Foner. Copyright © 2008 by W.W. Norton & Co. Inc. "A. Lincoln, Commander in Chief" copyright © by James M. McPherson. With the permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Co. Inc