In Land of Lincoln, Long-Buried Traces of a Race Riot Come to the Surface

Archaeologists recently uncovered the remains of five houses that lay witness to the tragedy that set Springfield, Illinois, on fire in 1908

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6a/29/6a2916f4-7087-40bd-8cc0-8926e94d0866/house_a_excavation_detail.jpg)

Recently, archaeologists uncovered the remains of five houses that once stood in a historically black neighborhood in Springfield, Illinois, until they were burned in a race riot 110 years ago. The carcasses of the structures are the last remaining witnesses to the lie that one Mabel Hallam told on a Thursday night in August of 1908 that set the hometown of Abraham Lincoln, “The Great Emancipator,” aflame.

A married white woman, Hallam claimed that summer she had been raped in her home by an unknown black man. The next morning, police searched for her alleged assailant, picking up black laborers who had been in her white working-class neighborhood. Hallam pointed to a brick carrier named George Richardson, identifying him as her rapist. Richardson was subsequently jailed alongside Joe James, another black man, who had been accused in July, on shaky circumstantial evidence, of fatally stabbing a white man during a break-in. By the afternoon, a white mob gathered outside the jail. Talk of a lynching spread.

Lynchings are most often associated with the Jim Crow-era South. The Equal Justice Initiative—the non-profit that opened the first U.S. monument to victims of lynching in Montgomery, Alabama, earlier this year— has documented 4,084 racial terror lynchings in 12 Southern states between 1877 and 1950. But EJI has also identified about 300 lynchings in other states during the same period. Such an event was not unheard of in Illinois, which had passed anti-lynching legislation in 1905 to prevent mob violence against African-Americans. And, as in the South, rape allegations like Hallam's were among the most common catalysts for a lynching. Those accusations could also serve as the pretense for violence directed at black communities in general.

**********

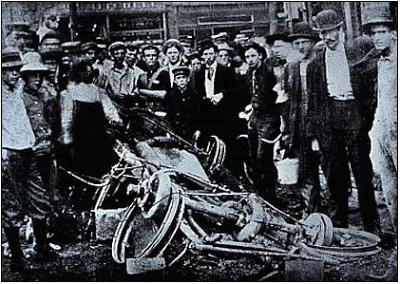

The Springfield sheriff watched the crowd grow. He hatched a plan to sneak Richardson and James out of the jail for their own safety, sending the prisoners north with the help of Harry Loper, a white restaurant owner who had a car. As the sun set, Richardson and James were miles away from danger, and the sheriff announced to the mob that the two prisoners were no longer in Springfield, assuming the crowd would disband and go home. He was sorely mistaken. A full-on riot began; the mob destroyed Loper’s restaurant and set his car on fire.

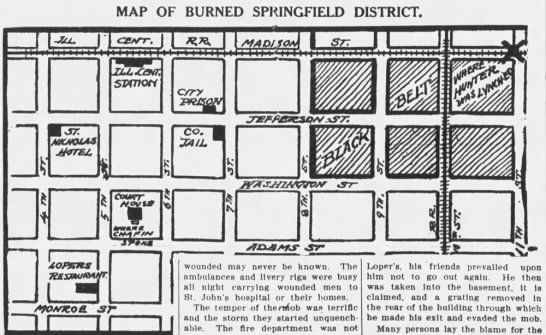

They then moved on to neighborhoods where African-Americans lived and worked, areas the local white press referred to as the Levee and the Badlands. The white rioters vandalized black-owned saloons, shops and other businesses. They systematically set homes of black residents ablaze, and beat those who hadn’t yet fled the neighborhoods, including an elderly man who suffered from paralysis. In the middle of the night, they dragged 56-year-old barber Scott Burton out of his home and lynched him; his body mutilated as it hung from a tree.

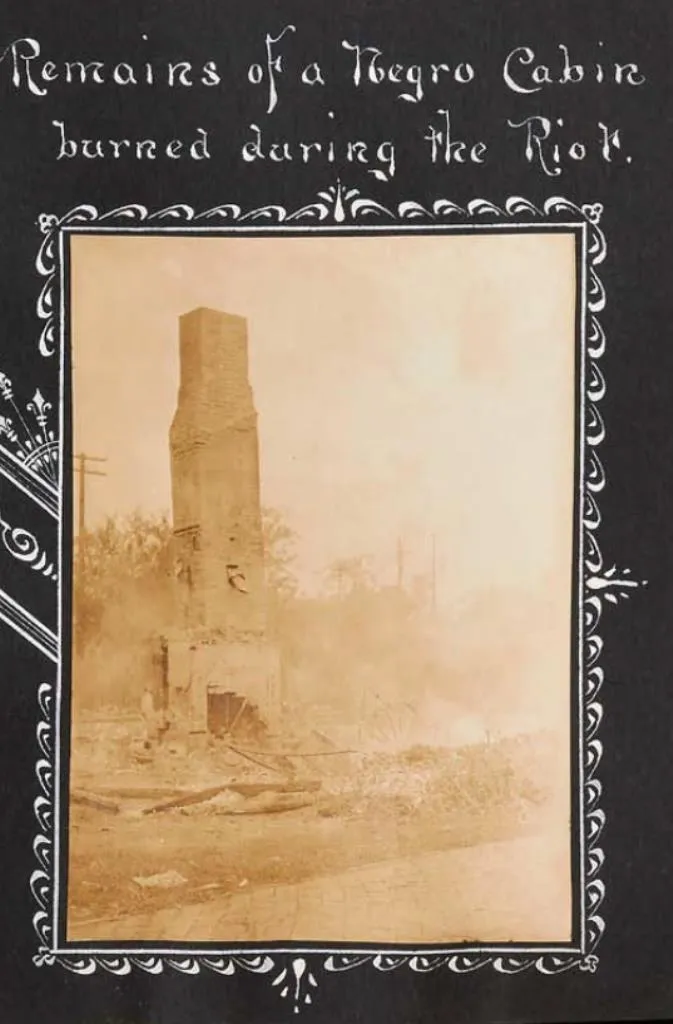

State militia troops finally scattered the mob on Saturday morning, but violence continued. That evening, the attackers moved on to another neighborhood and lynched William Donnegan, an 84-year-old shoemaker and wealthy black resident of Springfield who was married to a younger white woman. Four white people died amid the mayhem, killed by the militia or hit by bullets from the mob. An untold number of people were injured. The Badlands was left in ruins, with about 40 homes razed. According to historian Roberta Senechal's detailed descriptions of the riot, local authorities proved ineffectual at best, complicit at worst.

**********

As Senechal writes in a summary of the riot, Springfield did "not look like a city on the verge of race war.” The economy was strong, whites had effectively shut blacks out of skilled jobs, and Springfield had a relatively slowly growing African-American community, with only about 2,500 black residents in 1908, making up just over 5 percent of the population. According to Senechal's assessment, the alleged murder and rape had perhaps stoked white fears about black crime, but the targets of the riot tells another story about the motivations of the mob.

“The first area targeted was the black business district,” Senechal writes. “The two blacks killed were well-off, successful businessmen who owned their own homes… Although what triggered the riot may have been anger over black crime, very clearly whites were expressing resentment over any black presence in the city at all. They also clearly resented the small number of successful blacks in their midst.”

In the immediate aftermath of the riot, the two lynching trees were picked apart by souvenir hunters who came from all over to see the smoldering ruins. The local white press helped provide justification for the violence, with one editorial declaring, “It was not the fact of the whites’ hatred toward the negroes, but of the negroes’ own misconduct, general inferiority or unfitness for free institutions that were at fault.” Isolated beatings and arson attacks continued. Whites who employed blacks received anonymous threatening letters.

Two weeks after the riot, Mabel Hallam, the woman whose story triggered the bloodshed, recanted her rape allegation, and admitted to a grand jury that she had never been attacked by a black man. The charges against George Richardson were dropped, and some rumors circulated about Hallam inventing the story to cover for an affair with a white lover.

Joe James, meanwhile, was threatened with a black effigy of himself hanging near the courthouse before his brief murder trial began. James, an out-of-towner who may have been only a teenager, was sentenced to death and executed, despite little evidence linking him to the crime.

In total, 107 indictments were issued to the rioters who had destroyed and looted homes and businesses, and participated in the murders of Burton and Donnegan. Only one person was convicted, of theft.

If there was any silver lining, news of the riot spread nationally and galvanized a group of reformers to meet in New York City to discuss a "new abolition movement.” They officially formed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People NAACP) six months later, on Lincoln’s birthday. The NAACP used legal actions, protest and publicity to fight for civil rights, and the group also investigated race riots and lynchings. As part of its anti-lynching activism, the group famously hung a flag that read "A Man Was Lynched Yesterday” outside of its New York offices.

In Springfield, however, most physical traces of the riot’s damage were demolished, intentionally forgotten by a municipality unwilling to deal with its history.

“Part of our past in this city was to eliminate all vestiges of this event," says archaeologist Floyd Mansberger. As part of “urban renewal” efforts, a large portion of the Badlands was cleared and built over with public housing complexes. Today a hospital expansion and a four-lane highway cut through parts of the area. “It’s all been sanitized,” Mansbgerger said.

But not everything could be erased.

**********

The excavation, which was prompted by a multi-million dollar construction project to renovate a train line in Springfield, has catalyzed new discussions in Springfield about how to preserve the memory of the riot—and started a push to protect the newly discovered site as a national monument.

The City of Springfield received a Federal Railroad Administration grant for rail improvements, and as per the terms of the grant, the main contractor hired Mansberger’s cultural resource management firm, Fever River Research, to investigate whether significant archaeological remains might be disturbed during construction. Mansberger says the archival record indicated that the projects’ boundaries included the location of houses destroyed during the riot, but he had no idea if those remains were still intact.

“Lo and behold, those house foundations had been covered up in that fall of 1908 and never really impacted since then,” says Mansberger. “The preservation was fairly remarkable. They were buried by a foot to two feet of post-1920s debris, just rubble, then it was more or less a parking lot.”

Mansberger’s team dug test pits inside the brick foundations of each house in 2014. They found ash and fire debris mixed with fragments of furniture like a wooden table and a ceramic toilet. They uncovered home goods such as cups, saucers, bowls, plates and platters that hadn’t been ransacked during the fire. They also excavated smoke-blackened personal items like fragments of a metal busk from a corset, a cuticle tool, a nail polish bottle, and a handmade cross from a rosary carved out of bone.

“It’s the small, subtle things that whack you in the head and say, hey, these are people that just trying to live and exist,” Mansberger says of the finds in the Badlands. The neighborhood had a bad reputation because of its poverty and run-down housing, but also, Senechal writes, because “city authorities, anxious to keep vice activities away from white areas, had allowed cheap saloons, houses of prostitution, and gambling dens to spread into it from downtown.”

The archaeological evidence Mansberger's team uncovered meets the criteria for the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, necessitating modifications to the project that would minimize the damage to the archaeological site. Several parties—including the local NAACP chapter and the Springfield & Central Illinois African-American History Museum—were consulted about the process.

This fall, the agencies overseeing the project reached an agreement: The new train tracks will be moved about 20 feet to leave one of the houses protected in the ground, while the other four houses will be excavated and reburied. Mansberger’s team has been given the green light to complete the dig, and he plans to do so starting this spring.

The excavation may offer more information about the individual occupants of the houses. Archival records indicate that the one of the homes, for instance, was occupied in August 1908 by Will Smith, the elderly paralyzed man who was severely beaten.

****

It’s unlikely any major revelations about what happened during those tragic days in 1908 will surface during the dig. But it will offer a window into what the neighborhood was like at that time. “It just gives us a sense of how things were,” Mansberger says. “It allows you to touch and interact with individuals who experienced that event.”

Such tangible traces of the event also present new possibilities for the riot to be remembered in Springfield.

“There was not much said about the race riot for nearly 80 years as it was a dark spot on the history of Springfield,” says Kathryn Harris, a board member of the Springfield and Central Illinois African-American History Museum. A documentary was made about it in the 1990s, and several exhibitions and events commemorated the 100th anniversary of the event in 2008. New markers were installed around the path of destruction in the city on the occasion of the 110th commemoration this year. But many in Illinois have not been formally educated about the riot.

“It has not been taught in schools—it still isn’t,” says Leroy Jordan, who was the first African-American man to become a teacher in Springfield Public Schools in 1965. “I take the position that every child that goes to public school or any school in the city should know that this occurred to make sure we don't repeat that stuff anymore.”

Jordan is part of the Faith Coalition for the Common Good, one of the groups that was consulted about the preservation of the archaeological site. He had wanted the entire row of houses to be left intact in the ground, but in light of the new preservation agreement, he hopes that the one remaining house will at least be accessible to visitors. “We like the idea of having a viewing area where students could look down and see the remnants,” Jordan says.

According to the State Journal-Register, the NAACP has presented to the city council a video illustrating a concept for a memorial at the site that would run alongside the train tracks. The proposed memorial would feature a remembrance garden, a bronze sculpture resembling a lynching tree, and a 300-foot-long metal sculpture with a “wound” at its center.

Some leaders, including U.S. Senator Tammy Duckworth, an Illinois Democrat, have called for the site to be additionally recognized as a national monument.

“If we truly want to learn from the lessons of the past to fight prejudice today and tomorrow, we must recognize this history and preserve it for future generations,” Duckworth wrote in a recent editorial in the State Journal-Register. She also called upon President Trump to designate the site as a national monument to bear witness to the violence that took place there.

“It is my hope that those who see these public acknowledgements will learn, if they do not already know, the story of this horrific event, appreciate it, and vow to never let such an event occur again—in Springfield, in Illinois, or in our nation,” Harris says.