Looking Back at George H.W. Bush’s Lifelong Career of Public Service

The former President, dead at 94 years old, was noteworthy for his “humanity and decency,” says a Smithsonian historian

:focal(335x214:336x215)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/f3/fff37e4f-ca94-4632-a317-f843968daae8/91t0072c_1.jpg)

Throughout his nearly 30-year career in government, former President George H.W. Bush, who died on Friday at the age of 94, served in a dizzying number of positions, from Texas state Republican Party chairman to the highest office of the land. In between, he served as a congressman, ambassador to the United Nations, chairman of the Republican National Committee, chief liaison to the People’s Republic of China and CIA director before becoming the 43rd Vice President of the United States in 1981. In 1988, he was elected president and served for a single term.

Bush was perhaps best known for his achievements in foreign policy. His presidency saw tectonic shifts in global politics, from the fall of the Berlin Wall to China’s brutal crackdown on protestors in Tiananmen Square. The Cold War ended on his watch, but Bush is also known for the war he began soon thereafter—the 1990-91 conflict in the Persian Gulf that pitted an unprecedented global coalition against Saddam Hussein and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

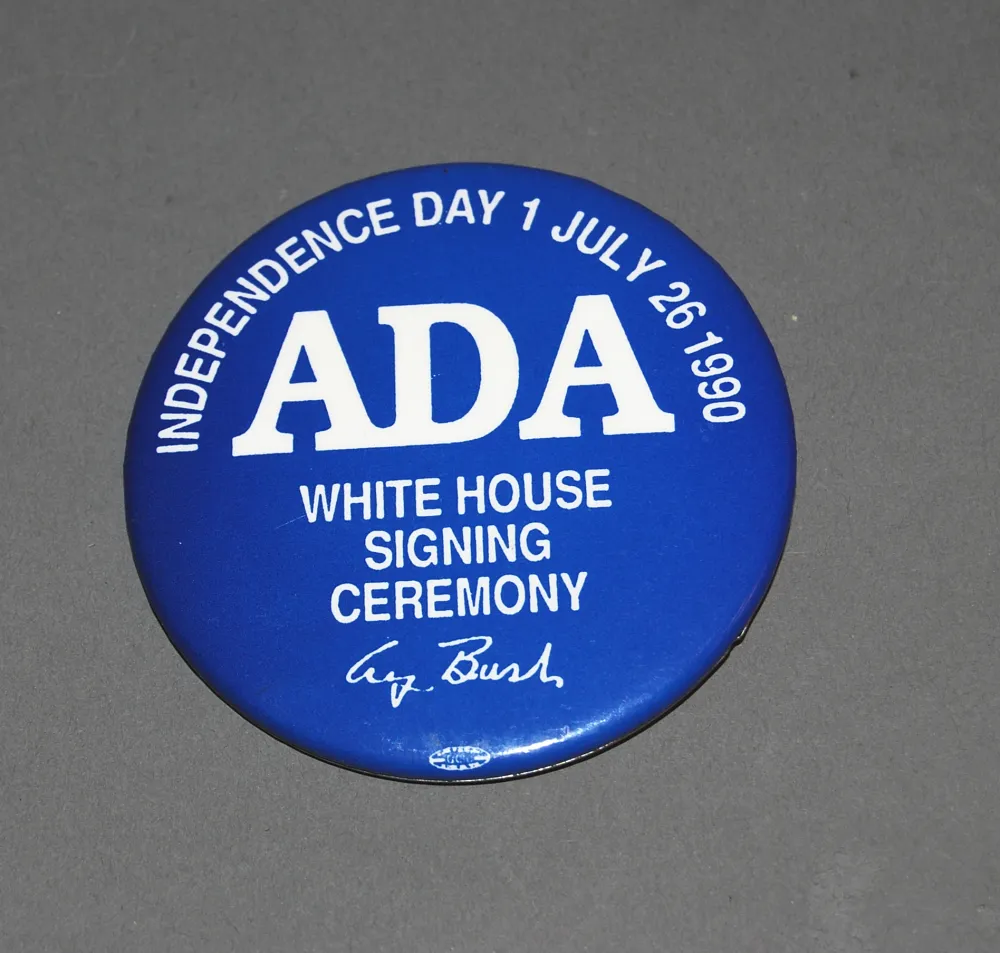

His domestic policy, though perhaps less dramatic than the events that transformed the world during his presidency, was characterized by pragmatic conservatism. Bush’s most famous campaign promise, the pithy “Read my lips: No new taxes” line he delivered during the 1988 Republican National Convention, came back to haunt him when he reversed his promise in order to achieve a budget compromise in a gridlocked Congress. But in this same speech he also dreamed of “a kinder, gentler nation, prompted by his desire to improve the lives of Americans and promote service,” says Claire Jerry, a curator at the National Museum of American History, over e-mail. “These were not just words to President Bush, as represented in two landmark bills he signed: the Americans With Disabilities Act and a tough amendment to the Clean Air Act, both in 1990.”

Despite a somewhat subdued reputation, the behind-the-scenes Bush was known as both caring and fond of pranks. He was also somewhat of a daredevil, enjoying a skydive as much as his favorite game of golf. He reprised his parachute jumping past several times in his older age, including on his 90th birthday.

But in the Oval Office, says David Ward, historian emeritus at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, Bush was best known as “a safe pair of hands.” For Ward, who during his 37 years at the museum served as steward to multiple portrayals of the president, Bush’s “element of humanity and decency needs to be acknowledged.”

That sense of decency shone through in Bush’s inaugural address, in which he used the phrase “a thousand points of light” to refer to the many organizations devoted to a better America. Though the point of the speech was to deflect state resources from social problems, says Ward, “nonetheless, it speaks to a kind of humanity toward people who are disadvantaged or unfortunate.”

**********

George Herbert Walker Bush was born on June 12, 1924, in Milton, Massachusetts. Nicknamed “Poppy,” he came from a privileged New England family that he would later spend decades trying to downplay.

Like so many other men of his generation, Bush’s young life was defined by the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The high-school senior, then attending the exclusive Phillips Academy, swiftly decided to join the U.S. Navy after graduation. When he did so, he became the United States’ youngest Navy pilot, serving in the Pacific theater throughout World War II.

Bush survived intense combat, including an incident in which he was nearly shot down by Japanese anti-aircraft guns. Overall, he flew 58 combat missions, achieved the rank of lieutenant, and was awarded three Air Medals and the Distinguished Flying Cross.

After World War II ended, Bush left the U.S. Navy. His first order of business after the war was to settle down with his new bride, Barbara Pierce, whom he married just months before leaving the service. Then, he focused on completing his education, earning his Bachelor of Arts in economics from Yale University in 1948.

Bush then turned his sights away from New England. He entered the oil industry, moved his family to Texas, and started working for a family friend before forming an oil development company. As an oil industry executive, he developed close ties in Texas and swiftly built a fortune, becoming a millionaire. Backed by solid social and business connections, he decided to follow in the footsteps of his father, who was elected as U.S. senator for Connecticut in 1952, and enter politics. In 1962, the year that his father left the Senate, Bush was named chairman of the Republican Party in Texas.

It was the beginning of a long career in public service and a steady rise through the Republican ranks. Though a few initial bids for a Senate seat were thwarted, he became a congressman in 1966. Despite voting mostly along conservative lines, he made a few noteworthy exceptions during his tenure in the House of Representatives, like when he voted for the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (most famous for its fair housing provisions) despite resistance within his home state.

Though he was re-elected to the House, Bush assented to the wishes of President Richard Nixon and ran for Senate in 1970. However, he lost to the Democratic candidate and his political career shifted. As penance, Nixon appointed him ambassador to the United Nations and Bush embarked on the next phase of his political career—a long stint in public service in which he seemed to be always the bridesmaid, but never the bride.

He was serving in one of those appointed political roles—chairman of the Republican National Committee—when the Watergate scandal broke out. Torn between defending the president and protecting the party, Bush eventually asked for Nixon’s resignation. He then became a contender to be Gerald Ford’s vice president, but the newly installed president instead opted for Nelson Rockefeller. He received an appointment as envoy to China instead, then called back to Washington by Ford to serve as the director of central intelligence. However, his term with the CIA was limited by that of his political patron, and when Jimmy Carter took office in 1977, he was replaced.

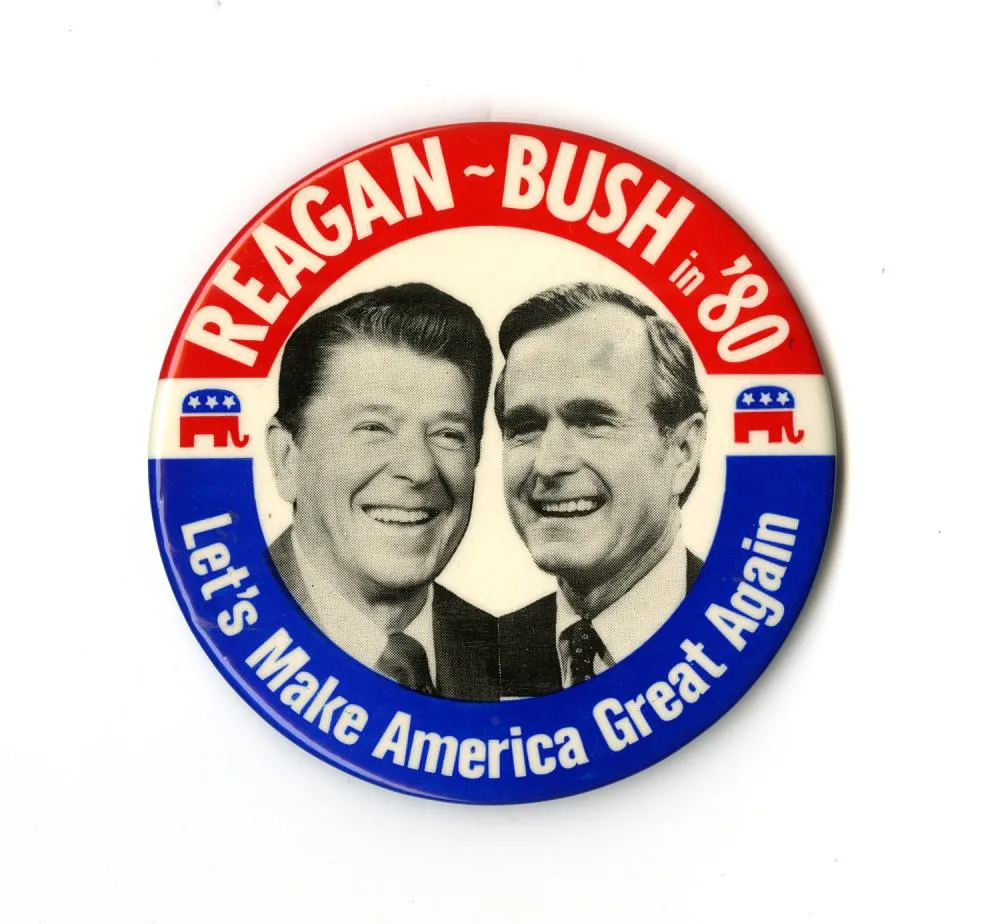

Bush then turned his attention to the national political stage, running for president in 1980. But his ascendance was again delayed, as California’s Ronald Reagan trounced him in the New Hampshire primary. Reagan would eventually pick him as his vice president, and Bush served a relatively low-key two terms, despite an eight-hour stint as the first-ever Acting President when Reagan had colon cancer surgery in 1985.

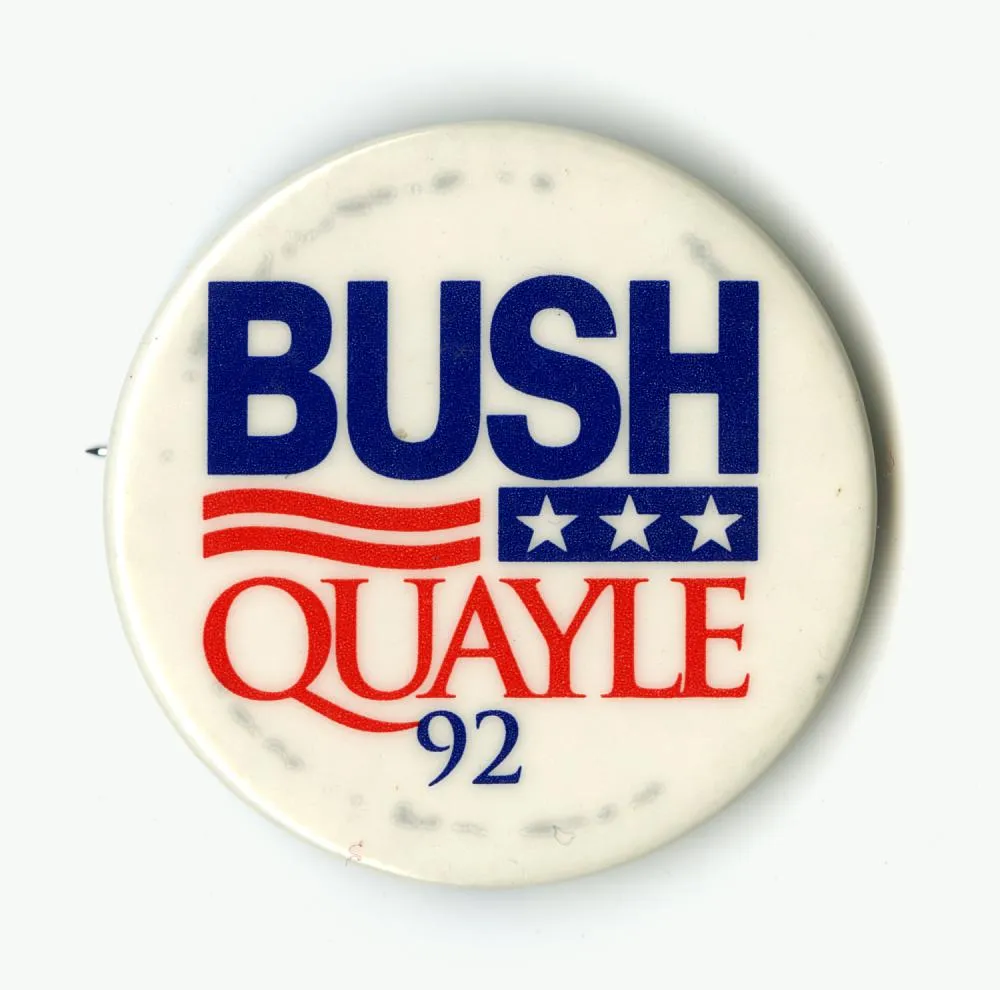

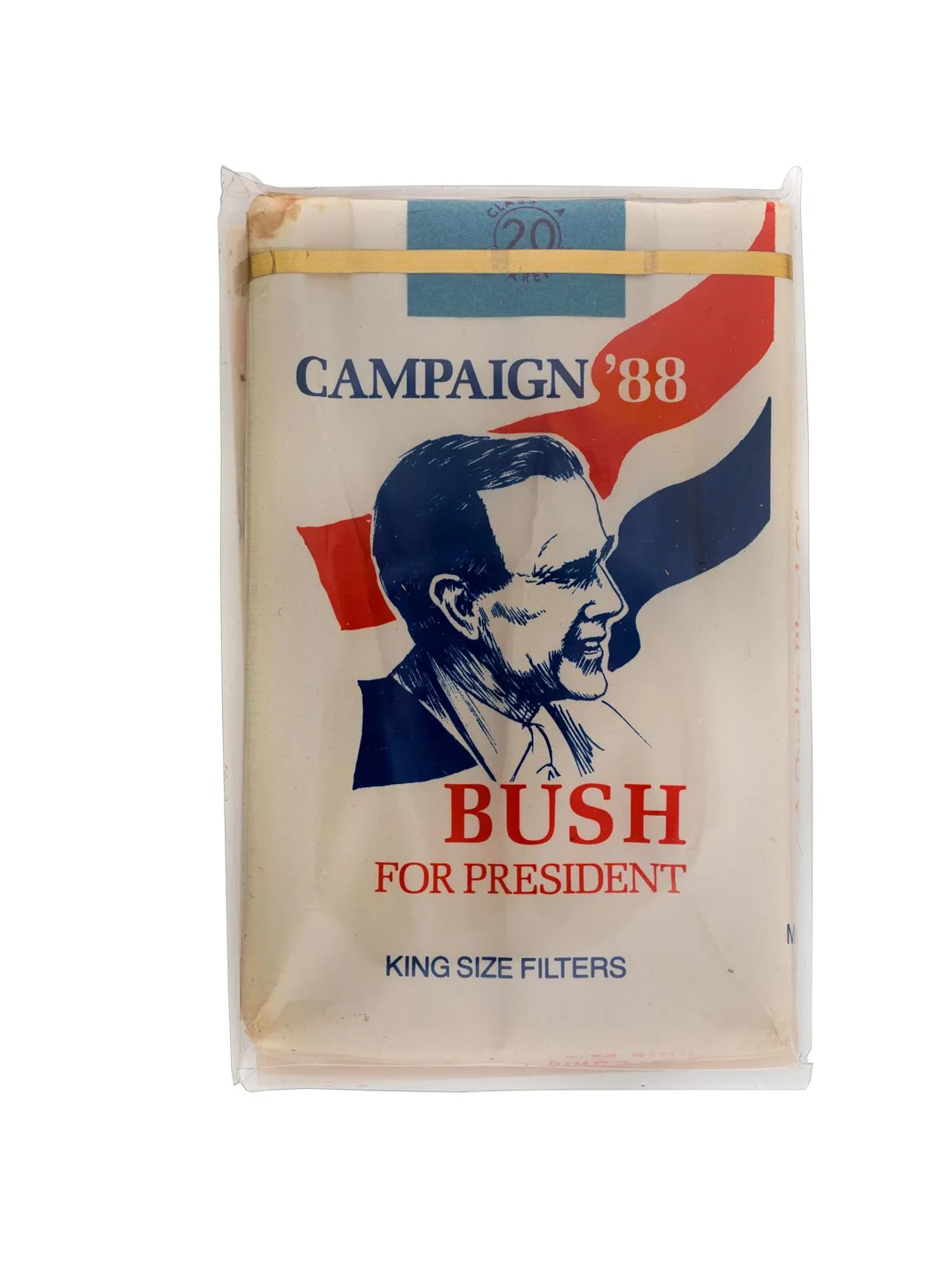

Despite operating in Reagan’s shadow, Bush managed to eke out a Republican presidential victory in 1988, though presidential historians think the win was due to lackluster Democratic candidate, Michael Dukakis, and not to Bush’s charisma. But Bush’s vision for the United States made a mark during the 1988 Republican National Convention, where he promised “no new taxes” and endorsed popular Republican values like gun rights and prayer in schools.

Within a year of Bush’s inauguration, Reagan-era deficits and political gridlock prompted him to go back on his “read my lips” promise. He paid the political price for that decision, but other presidential moves, like entering the Gulf War along with an international coalition, were well regarded. He also solidified his future legacy by helping negotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement, laying the foundation for its eventual passage during Bill Clinton’s presidency.

But not all would speak so positively of Bush’s legacy. A racist ad run during the presidential election portrayed escaped convict William Horton as an example of the crime that would supposedly result if Dukakis were elected president. Though the campaign denied they were involved in the advertisement, scholars like political scientist Tali Mendelberg argue that Bush and his campaign strategists benefitted from how it stirred up racial bias and fear in potential constituents. The year earlier, as vice president, Bush was booed when he took the stage of the third International Conference on AIDS, a reflection on the Reagan administration's lack of action during the AIDS crisis. According to the Los Angeles Times’ Marlene Cimons and Harry Nelson, Bush asked if the protest was due to “some gay group out there,” and he never used the word “gay” in an official capacity during his presidency. Additionally, his presidential administration's “War on Drugs,” waged in the shadow of his predecessors, resulted in racial disparities in arrests, sentencing and outcomes.

Bush ran for re-election, but once again he was overshadowed by a more charismatic presidential candidate. In 1992, after losing his campaign to Clinton, Bush prepared for life after the White House—one that involved working with the Points of Light Foundation, a nonprofit that connects volunteers and service opportunities, raising funds in the wake of natural disasters like the 2004 tsunami in southeast Asia, and working on his presidential library and museum in College Station.

In retrospect, Bush’s long life of service seems remarkable primarily because of his perseverance. But though he left office with his colleagues’ respect, he did not escape criticism during his years in Washington. Though he was disillusioned with President Nixon’s involvement with the Watergate affair, he had to serve as the Republican Party’s public face during the contentious period of its discovery and Nixon’s resignation.

Nor did he emerge from either his vice presidency or presidency unscathed: Not only was he suspected of knowing more than he revealed about the Iran-Contra affair, but he presided over a recession while in office.

Since his presidency, Bush never strayed far from the White House to which he devoted so much of his life—but true to form, his work often took place in the background through advice, service, and fundraising.

So what did the oldest living president have to say about his single term while he was still alive? True to form, he called his legacy “the L word”—and forbade staff from discussing it in his presence. He may have often stayed offstage. But with his death will come the presidential pageantry that is his due—and a reassessment of a legacy that has only sharpened with age.

Pay your respects to President Bush at the National Portrait Gallery, where his official portrait has been draped and a guest book is available for visitors to offer their thoughts on his legacy.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)