The Couple Who Saved China’s Ancient Architectural Treasures Before They Were Lost Forever

As the nation teetered on the brink of war in the 1930s, two Western-educated thinkers struck out for the hinterlands to save their country’s riches

:focal(530x214:531x215)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a8/a7/a8a783bb-b438-4bc4-9c64-d44cf1cb2208/janfeb2017_f08_shanxi-wr-v3.jpg)

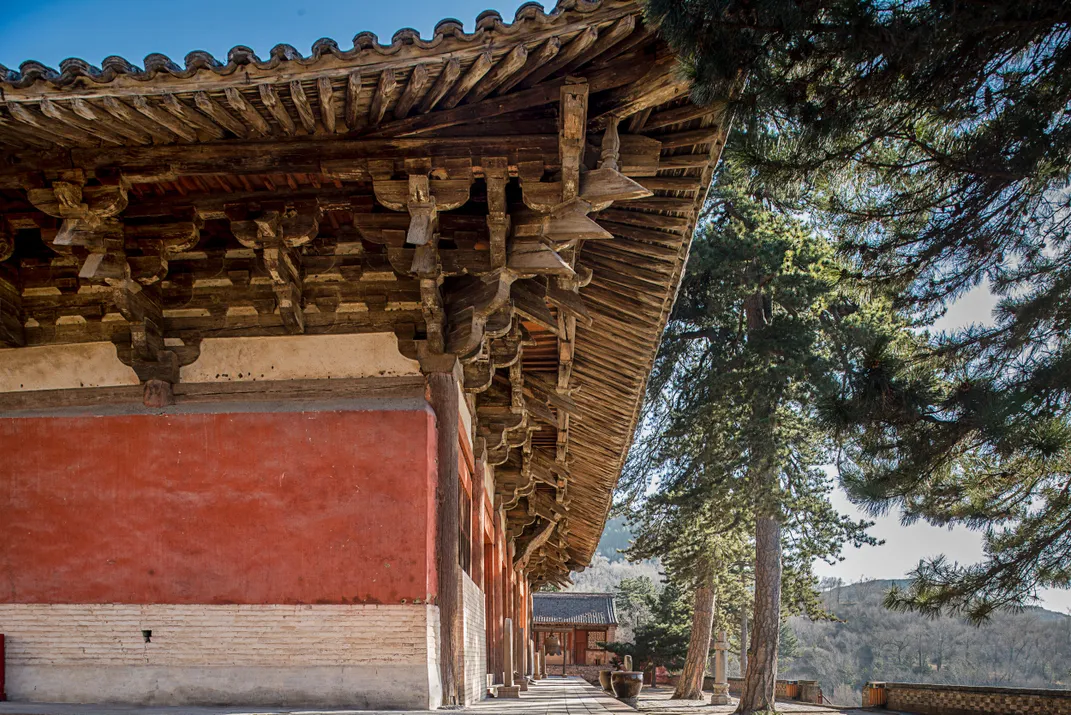

Architectural preservation is rarely so thrilling as it was in 1930s China. As the country teetered on the edge of war and revolution, a handful of obsessive scholars were making adventurous expeditions into the country’s vast rural hinterland, searching for the forgotten treasures of ancient Chinese architecture. At the time, there were no official records of historic structures that survived in the provinces. The semi-feudal countryside had become a dangerous and unpredictable place: Travelers venturing only a few miles from major cities had to brave muddy roads, lice-infested inns, dubious food and the risk of meeting bandits, rebels and warlord armies. But although these intellectuals traveled by mule cart, rickshaw or even on foot, their rewards were great. Within the remotest valleys of China lay exquisitely carved temples staffed by shaven-headed monks much as they had been for centuries, their roofs filled with bats, their candlelit corridors lined with dust-covered masterpieces.

The two leaders of this small but dedicated group have taken on a mythic status in China today: the architect Liang Sicheng and his brilliant poet wife, Lin Huiyin. This prodigiously talented couple, who are now revered in much the same way as Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Mexico, were part of a new generation of Western-educated thinkers who came of age in the 1920s. Born into aristocratic, progressive families, they had both studied at the University of Pennsylvania and other Ivy League schools in the United States, and had traveled widely in Europe. Overseas, they were made immediately aware of the dearth of studies on China’s rich architectural tradition. So on their return to Beijing, the cosmopolitan pair became pioneers of the discipline, espousing the Western idea that historic structures are best studied by firsthand observation on field trips.

This was a radical idea in China, where scholars had always researched the past through manuscripts in the safety of their libraries, or at most, made unsystematic studies of the imperial palaces in Beijing. But with flamboyant bravado, Liang and Lin—along with a half dozen or so other young scholars in the grandly named Institute for Research in Chinese Architecture—used the only information available, following stray leads in ancient texts, chasing up rumors and clues found in cave murals, even, in one case, an old folkloric song. It was, Liang later wrote, “like a blind man riding a blind horse.”

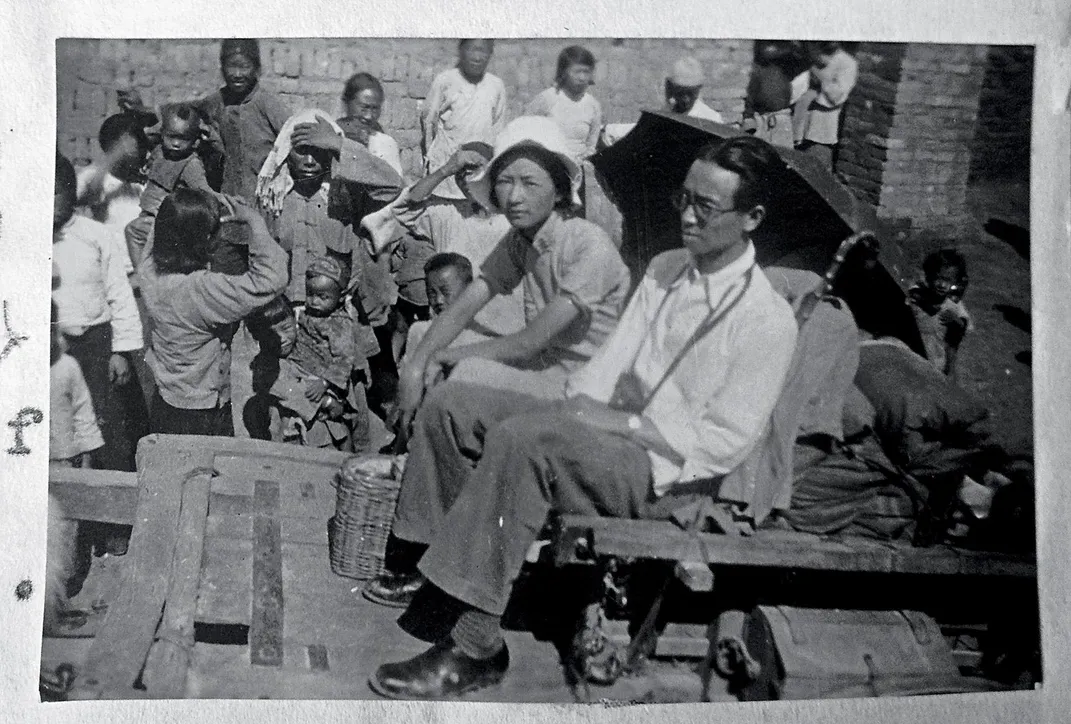

Despite the difficulties, the couple would go on to make a string of extraordinary discoveries in the 1930s, documenting almost 2,000 exquisitely carved temples, pagodas and monasteries that were on the verge of being lost forever. Photographs show the pair scrambling among stone Buddhas and across tiled roofs, Liang Sicheng the gaunt, bespectacled and reserved aesthete, scion of an illustrious family of political reformers (on par with being a Roosevelt or Kennedy in the U.S.), Lin Huiyin the more extroverted and effervescent artist, often wearing daring white sailor slacks in the Western fashion. The beautiful Lin was already legendary for the romantic passions she had inspired, leaving a trail of lovelorn writers and philosophers, including the renowned Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, who once composed a poem in praise of her charms. (“The blue of the sky / fell in love with the green of the earth. / The breeze between them sighs, ‘Alas!’”)

“Liang and Lin founded the entire field of Chinese historical architecture,” says Nancy Steinhardt, professor of East Asian art at the University of Pennsylvania. “They were the first to actually go out and find these ancient structures. But the importance of their field trips goes beyond that: So many of the temples were later lost—during the war with Japan, the revolutionary civil war and the Communist attacks on tradition like the Cultural Revolution—that their photos and studies are now invaluable documents.”

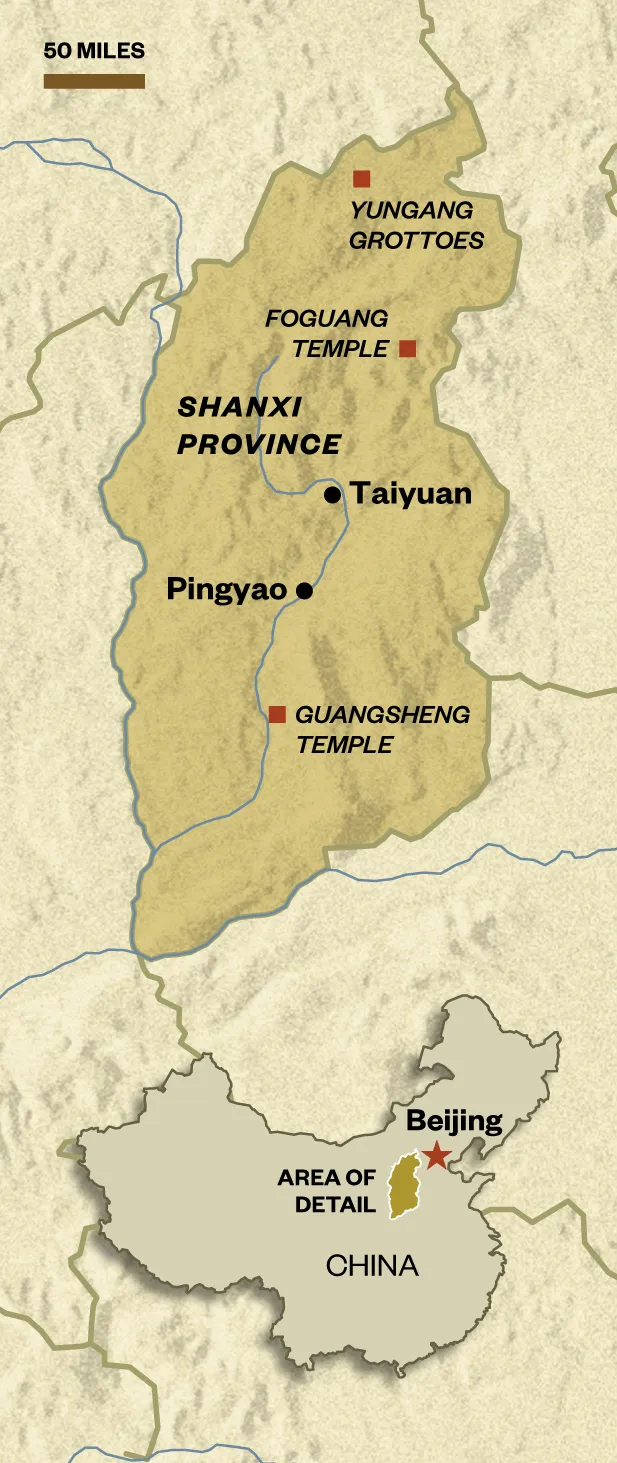

The romantic pair, whose letters are suffused with a love of poetry and literature, returned most often to the province of Shanxi (“west of the mountains”). Its untouched landscape was the ultimate time capsule from imperial China. An arid plateau 350 miles from Beijing, cut off by mountains, rivers and deserts, Shanxi had avoided China’s most destructive wars for over 1,000 years. There had been spells of fabulous prosperity as late at the 19th century, when its merchants and bankers managed the financial life of the last dynasty, the Qing. But by the 1930s, it had drifted into impoverished oblivion—and poverty, as the axiom goes, is the preservationist’s friend. Shanxi, it was found, resembled a living museum, where an astonishing number of ancient structures had survived.

One of the most significant excursions to Shanxi occurred in 1934, when Liang and Lin were joined by two young American friends, John King Fairbank and his wife, Wilma. The couples had met through friends, and the Fairbanks became regular guests at the salons hosted by Liang and Lin for Chinese philosophers, artists and writers. It was an influential friendship: John, a lanky, sandy-haired South Dakotan, would go on to become the founding figure in Sinology in the United States, and an adviser to the U.S. government on Chinese policy from World War II to the 1970s. (The prestigious Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University bears his name.) Wilma was a fine arts major from Radcliffe, a feisty New Englander in the mold of Katharine Hepburn, who would later become an authority on Chinese art in her own right, and play a key role in saving Liang and Lin’s work from oblivion.

But in the summer of 1934, the Fairbanks were two wide-eyed newlyweds in Beijing, where John was researching his PhD in Chinese history, and they eagerly agreed to meet the Liangs in Shanxi. The four spent several weeks making forays from an idyllic mountain retreat called Fenyang, before they decided to find the remote temple of Guangsheng. Today, the details of this 1934 journey can be reconstructed from an intimate photographic diary made by Wilma Fairbank and from her memoir. The prospect of the 70 miles of travel had at first seemed “trivial,” Wilma noted, but it became a weeklong expedition. Summer rains had turned the road to “gumbo,” so the antique Model T Ford they had hired gave out after ten miles. They transferred their luggage to mule carts, but were soon forced by the soldiers of the local warlord Yan Shinxan, who were building a railroad line along the only roads, to take the back trails, which were traversable only by rickshaw. (John was particularly uncomfortable being pulled by human beings, and sympathized when the surly drivers complained, “We have been doing ox and horse work.”) When the tracks became “bottomless jelly,” the four were forced to walk, led after dark by a child carrying a lantern. Liang Sicheng battled on through the mire, despite his near-lame leg, the result of a youthful motorbike accident.

The inns en route were dismal, so they looked for alternative arrangements, sleeping one night in an empty Ming dynasty mansion, others in the homes of lonely missionaries. All along the route they were surrounded by peasants who stared in wonder at Liang and Lin, unable to conceive of Chinese gentry taking an interest in their rural world. Often, the histrionic Lin Huiyin would fall into “black moods” and complain vociferously about every setback, which astonished the stiff-upper-lipped, WASPish Wilma Fairbank. But while the diva poet could be “unbearable,” Wilma conceded, “when she was rested she responded to beautiful views and humorous encounters with utter delight.”

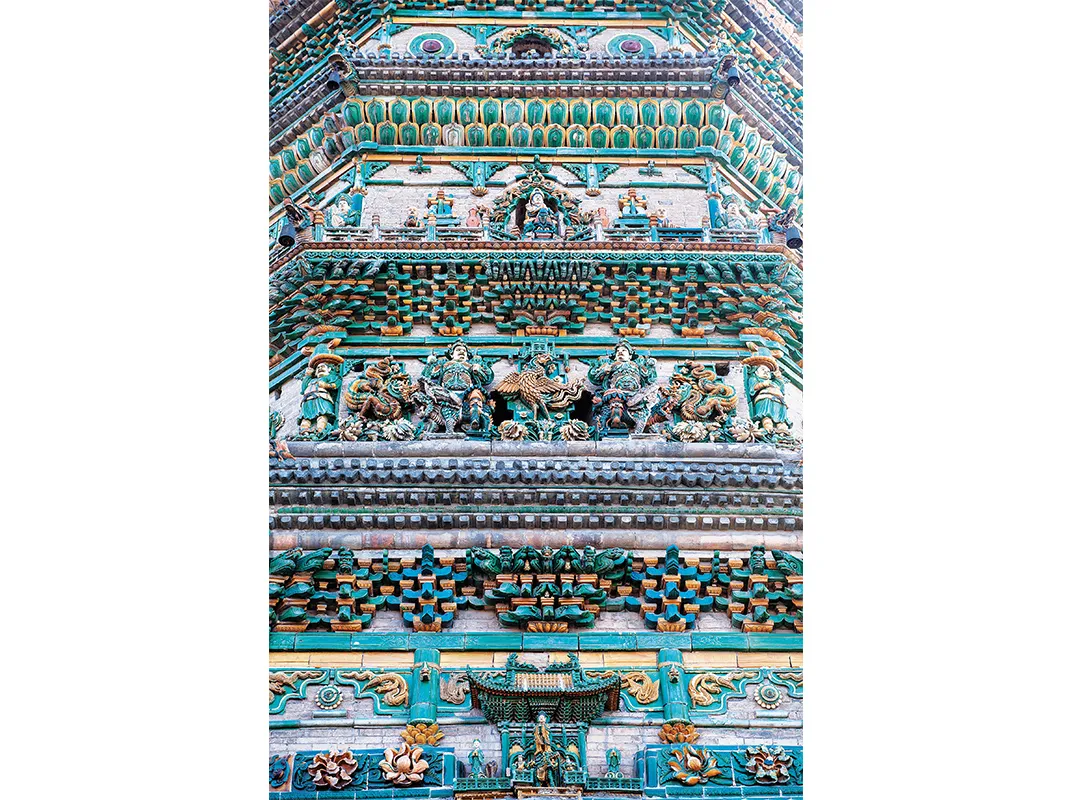

The discomforts were instantly forgotten when the exhausted party finally spotted the graceful proportions of the Guangsheng Temple one dusk. The monks allowed the Fairbanks to sleep in the moonlit courtyard, while the Liangs set up their cots beneath ancient statues. Next morning, the Liangs marveled at the temple’s inventive structural flourishes created by a nameless ancient architect, and found a fascinating mural of a theatrical performance from A.D. 1326. They climbed a steep hill to the Upper Temple, where a pagoda was encrusted in colored glazed tiles. Behind the enormous Buddha’s head was a secret staircase, and when they reached the 13th story, they were rewarded with sweeping views of the countryside, as serene as a Ming watercolor.

The years of field trips would ultimately represent an interlude of dreamlike contentment for Liang and Lin, as their lives were caught in the wheels of Chinese history. All explorations in northern China were halted by the Japanese invasion in 1937, which forced the couple to flee Beijing with their two young children to ever-harsher and more distant refuges. (The Fairbanks had left one year earlier, but John returned as a U.S. intelligence officer during World War II and Wilma soon after.) There was a moment of hope after the Japanese surrender, when Liang and Lin were welcomed back to Beijing as leading intellectuals, and Liang, as “the father of modern Chinese architecture,” returned to the United States to teach at Yale in 1946 and work with Le Corbusier on the design of the United Nations Plaza in New York. But then came the Communist triumph in 1949. Liang and Lin initially supported the revolution, but soon found themselves out of step with Mao Zedong’s desire to eradicate China’s “feudal” heritage. Most famously, the pair argued passionately for the preservation of Beijing, then the world’s largest and most intact walled city, considered by many as beautiful as Paris. Tragically, Mao ordered its 25 miles of fortress walls and many of its monuments destroyed—which one U.S. scholar has denounced as “among the greatest acts of urban vandalism in history.”

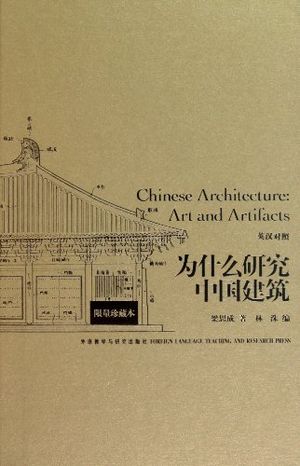

The rest of their lives have a tragic aura. Lin Huiyin, who had always been frail, succumbed to a long battle with tuberculosis in 1955, and Liang, despite his international renown, was trapped in 1966 by the anti-intellectual mania of the Cultural Revolution. The frenzied attack on Chinese tradition meant that Liang was forced to wear a black placard around his neck declaring him a “reactionary academic authority.” Beaten and mocked by Red Guards, stripped of his honors and his position, Liang died brokenhearted in a one-room garret in 1972, convinced that he and his wife’s life’s work had been wasted. Miraculously, he was wrong, thanks to the dramatic volte-face of China’s modern history. After the death of Mao in 1976, Liang Sicheng was among the first wave of persecuted intellectuals to be rehabilitated. Lin Huiyin’s poetry was republished to widespread acclaim, and Liang’s portrait even appeared on a postage stamp in 1992. In the 1980s, Fairbank managed to track down the pair’s drawings and photographs from the 1930s, and reunite them with a manuscript Liang had been working on during World War II. The posthumous volume, An Illustrated History of Chinese Architecture, became an enduring testament to the couple’s work.

Today, the younger generations of Chinese are fascinated by these visionary figures, whose dramatic lives have turned them into “cultural icons, almost with demigod status,” says Steinhardt of the University of Pennsylvania. The dashing pair have been the subjects of TV documentaries, and Lin Huiyin’s love life has been pored over in biographies and soap operas. She is regularly voted the most beautiful woman in Chinese history and will be played in an upcoming feature film by the sultry actress Zhang Ziyi, of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon fame. “For Chinese women, Lin Huiyin seems to have it all,” says Annie Zhou, Lin’s great-granddaughter, who was raised in the United States. “She’s smart, beautiful and independent. But there’s also a nostalgia for her world in the 1920s and ’30s, which was the intellectual peak of modern Chinese history.”

“Since when did historical preservationists get to be so sexy?” muses Maya Lin, the famous American artist and architect, who happens to be Lin Huiyin’s niece. Talking in her loft-studio in downtown Manhattan, Maya pointed through enormous windows at the cast-iron district of SoHo, which was saved by activists in New York in the 1960s and ’70s. “They’ve become folk heroes in China for having stood up for preservation, like Jane Jacobs here in New York, and they are celebrities in certain academic circles in the United States.” She recalls being cornered by elderly (male) professors at Yale who raved about meeting her aunt, their eyes lighting up when they spoke of her. “Most people in China know more about Liang and Lin’s personalities and love lives than their work. But from an architectural point of view, they are hugely important. If it weren’t for them, we would have no record of so many ancient Chinese styles, which simply disappeared.”

Since China’s embrace of capitalism in the 1980s, a growing number of Chinese are realizing the wisdom of Liang and Lin’s preservation message. As Beijing’s wretched pollution and traffic gridlock have reached world headlines, Liang’s 1950 plan to save the historic city has taken on a prophetic value. “I realize now how terrible it is for a person to be so far ahead of his time,” says Hu Jingcao, the Beijing filmmaker who directed the documentary Liang and Lin in 2010. “Liang saw things 50 years before everyone else. Now we say, Let’s plan our cities, let’s keep them beautiful! Let’s make them work for people, not just cars. But for him, the idea only led to frustration and suffering.”

The situation is more encouraging in Liang and Lin’s favorite destination, Shanxi. The isolated province still contains around 70 percent of China’s structures older than the 14th century—and the couple’s magnum opus on Chinese architecture can be used as a unique guidebook. I had heard that the most evocative temples survive there, although they take some effort to reach. The backwaters of Shanxi remain rustic, their inhabitants unused to foreigners, and getting around is still an adventure, even if run-ins with warlords have been phased out. A renewed search for the temples would provide a rare view back to the 1930s, when China was poised on the knife-edge of history, before its slide into cataclysmic wars and Maoist self-destruction.

Of course, historic quests in modern China require some planning. It’s one of the ironies of history that the province containing the greatest concentration of antiquities has also become one of the most polluted spots on the planet. Since the 1980s, coal-rich Shanxi has sold its black soul to mining, its hills pockmarked with smelters churning out electricity for the country’s insatiable factories. Of the world’s most polluted cities, 16 of the top 20 are in China, according to a recent study by the World Bank. Three of the worst are in Shanxi.

I had to wonder where Liang and Lin would choose as a base today. As the plane approached Taiyuan, the provincial capital, and dove beneath rust-colored layers of murk, the air in the cabin suddenly filled with the smell of burning rubber. This once-picturesque outpost, where Liang and Lin clambered among the temple eaves, has become one of China’s many anonymous “second-tier” cities, rung by shabby skyscrapers. Other Shanxi favorites have suffered in the development craze. In the grottoes of Yungang, whose caves full of giant carved Buddhas were silent and eerie when Lin sketched them in 1931, riotous tour groups are now funneled through an enormous new imperial-style entrance, across artificial lakes and into faux palaces, creating a carnival atmosphere.

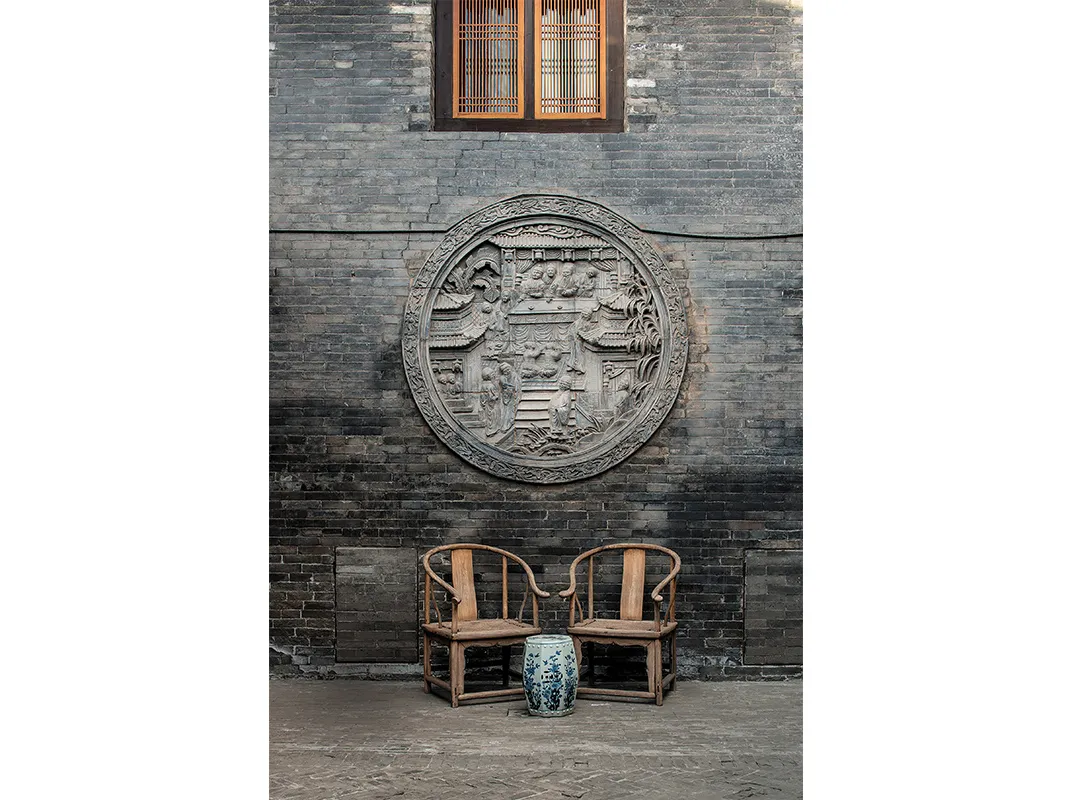

But luckily, there is still a place where Liang and Lin would feel happy —Pingyao, China’s last intact walled town, and one of its most evocative historic sites. When the pair was traveling in the 1930s, dozens and dozens of these impressive fortress towns were scattered across the Shanxi plains. In fact, according to the imperial encyclopedia of the 14th century, there were 4,478 walled towns in China at one time. But one by one their defenses were knocked down after the revolution as symbols of the feudal past. Pingyao survived only because authorities in the poor district lacked the resources to topple its formidable fortifications, which are up to 39 feet thick, 33 feet high and topped with 72 watchtowers. The crenelated bastions, dating from 1370, also enclosed a thriving ancient town, its lane ways lined with lavish mansions, temples and banks dating from the 18th century, when Pingyao was the Qing dynasty’s financial capital.

A dusty highway now leads to Pingyao’s enormous fortress gates, but once inside, all vehicular traffic is forced to stop. It is an instant step back to the elusive dream of Old China. On my own visit, arriving at night, I was at first disconcerted by the lack of street lighting. In the near-darkness, I edged along narrow cobbled alleys, past noodle shops where the cooks were bent over bubbling caldrons. Street vendors roasted kebabs on charcoal grills. Soon my eyes adjusted to the dark, and I spotted rows of lanterns illuminating ornate facades with gold calligraphy, all historic establishments dating from the 16th to 18th centuries, including exotic spice merchants and martial arts agencies that had once provided protection for banks. One half-expects silk-robed kung fu warriors to appear, tripping lightly across the terra-cotta tile roofs à la Ang Lee.

Liang and Lin’s spirits hover over the remote town today. Having survived the Red Guards, Pingyao became the site of an intense conservation battle in 1980, when the local government decided to “rejuvenate” the town by blasting six roads through its heart for car traffic. One of China’s most respected urban historians, Ruan Yisan of Shanghai’s Tongji University—who met Lin Huiyin in the early 1950s and attended lectures given by Liang Sicheng—arrived to halt the steamrollers. He was given one month by the state governor to devise an alternative proposal. Ruan took up residence in Pingyao with 11 of his best students and got to work, braving lice, rock-hard kang beds with coal burners beneath them for warmth, and continual bouts of dysentery. Finally, Ruan’s plan was accepted, the roads were diverted and the old town of Pingyao was saved. His efforts were rewarded when Unesco declared the entire town a World Heritage site in 1997. Only today is it being discovered by foreign travelers.

The town’s first upscale hotel, Jing’s Residence, is housed inside the magnificent 18th-century home of a wealthy silk merchant. After an exacting renovation, it was opened in 2009 by a coal baroness named Yang Jing, who first visited Pingyao 22 years ago while running an export business. Local craftsmen employed both ancient and contemporary designs in the interior, and the chef specializes in modern twists on traditional dishes, such as the local corned beef served with cat’s ear-shaped noodles.

Many Chinese are now visiting Pingyao, and although Prof. Ruan Yisan is 82 years old, he returns every summer to monitor its condition and lead teams on renovation projects. I met him over a banquet in an elegant courtyard, where he was addressing fresh-faced volunteers from France, Shanghai and Beijing for a project that would now be led by his grandson. “I learned from Liang Sicheng’s mistakes,” he declared, waving his chopsticks theatrically. “He went straight into conflict with Chairman Mao. It was a fight he couldn’t win.” Instead, Ruan said, he preferred to convince government officials that heritage preservation is in their own interest, helping them improve the economy by promoting tourism. But, as ever, tourism is a delicate balancing act. For the moment, Pingyao looks much as it did when Liang and Lin were traveling, but its population is declining and its hundreds of ornate wooden structures are fragile. “The larger public buildings, where admission can be charged, are very well maintained,” Ruan explained. “The problem is now the dozens of residential houses that make up the actual texture of Pingyao, many of which are in urgent need of repair.” He has started the Ruan Yisan Heritage Foundation to continue his efforts to preserve the town, and he believes a preservation spirit is spreading in Chinese society—if gradually.

The hotelier Yang Jing agrees: “At first, most Chinese people found Pingyao too dirty,” she said. “They certainly didn’t understand the idea of a ‘historic hotel,’ and would immediately ask to change to a bigger room, then leave after one night. They wanted somewhere like a Hilton, with a big shiny bathroom.” She added with a smile: “But it has been slowly changing. People are tired of Chinese cities that all look the same.”

Poring over Liang and Lin’s Illustrated History, I drew up a map of the couple’s greatest discoveries. While Shanxi is little visited by travelers, its rural villages seem to have fallen off the charts entirely. Nobody in Pingyao had even heard of the temples I spoke about, although they were included on detailed road charts. So I was forced to cajole wary drivers to take me to visit the most sacred, forgotten spots.

Some, like the so-called Muta, China’s tallest wooden pagoda dating from 1056, were easy to locate: The highway south of Datong runs alongside it, so it still rises gracefully over semi-suburban farmland. Others, like the Guangsheng Temple, which Liang and Lin visited with the Fairbanks in 1934, involved a more concerted effort. It lies in the hills near Linfen, now one of the most toxic of Shanxi’s coal outposts. (In 2007, Linfen had the honor of being declared “the world’s most polluted city.”) Much of the landscape is now completely disguised by industry: Mountains are stripped bare, highways are clogged with coal trucks. Back in 1934, Lin Huiyin had written, “When we arrived in Shanxi, the azure of the sky was nearly transparent, and the flowing clouds were mesmerizing.... The beauty of such scenery pierced my heart and even hurt a little.” Today, there are no hints of azure. A gritty mist hangs over everything, concealing all views beyond a few hundred yards. It’s a haunted landscape where you never hear birds or see insects. Here, the silent spring has already arrived.

Finally, the veil of pollution lifts as the road rises into the pine-covered hills. The Lower Temple of Guangsheng is still announced by a bubbling emerald spring, as it was in 1934, and although many of the features were vandalized by Japanese troops and Red Guards, the ancient mural of the theatrical performance remains. A monk, one of 20 who now live there, explained that the Upper Temple was more intact. (“The Red Guards were too lazy to climb there!”) I counted 436 steps up to the hill crest, where the lovely 13-story pagoda was still gleaming with colored glazed tiles. Another monk was meditating cross-legged, as a cassette recorder played Om Mani Padme Hum.

I was determined to find the “secret” stairway. After making endless inquiries, I convinced a guard to wake the abbot from his afternoon nap and got a key. He led me into the pagoda and opened a grille to the second level, now followed by a couple of other curious monks. It was pitch black, so I used the light from my iPhone to peer behind an enormous grinning Buddha. Sure enough, there were worn stone steps leading up. Wilma described the staircase’s unique design: “We groped our way up in single file. At the top of the first flight, we were startled to find that there were no landings. When you bumped your head against a blank wall you knew you had come to the end of one flight of stairs. You had to turn around there and step over empty space onto the first step of the next flight.” I eagerly pressed ahead—but was soon blocked by another padlocked grille, whose key, the guard remembered, was kept by a government official in the faraway capital, no doubt in his desk drawer. Still, as I crouched in the darkness, I could glimpse that the ancient architect really had not put a landing, for reasons we will never know.

Liang and Lin’s greatest triumph came three years later. Their dream had always been to find a wooden temple from the golden age of Chinese art, the glorious Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-907). It had always rankled that Japan claimed the oldest structures in the East, although there were references to far more ancient temples in China. But after years of searching, the likelihood of finding a wooden building that had survived 11 centuries of wars, periodic religious persecutions, vandalism, decay and accidents had begun to seem fantastical. (“After all, a spark of incense could bring down an entire temple,” Liang fretted.) In June 1937, Liang and Lin set off hopefully into the sacred Buddhist mountain range of Wutai Shan, traveling by mule along serpentine tracks into the most verdant pocket of Shanxi, this time accompanied by a young scholar named Mo Zongjiang. The group hoped that, while the most famous Tang structures had probably been rebuilt many times over, those on the less-visited fringes might have endured in obscurity.

The actual discovery must have had a cinematic quality. On the third day, they spotted a low temple on a crest, surrounded by pine trees and caught in the last rays of sun. It was called Foguang Si, the Temple of Buddha’s Light. As the monks led them through the courtyard to the East Hall, Liang and Lin’s excitement mounted: A glance at the eaves revealed its antiquity. “But could it be older than the oldest wooden structure we had yet found?” Liang later wrote breathlessly.

Today, Wutai Shan’s otherworldly beauty is heightened by a blissful lack of pollution. From winding country roads that seemed to climb forever, I looked down at immense views of the valleys, then stared up in grateful acknowledgment of the blue sky. The summer air was cool and pure, and I noticed that many of the velvety green mountains were topped with their own mysterious monasteries. The logistics of travel were also reminiscent of an earlier age. Inside the rattling bus, pilgrims huddled over their nameless food items, each sending a pungent culinary odor into the exotic mix. We arrived at the only town in the mountain range, a Chinese version of the Wild West, where the hotels seem to actually pride themselves on provincial inefficiency. I took a room whose walls were covered in three types of mold. In the muddy street below, dogs ran in and out of stores offering cheap incense and “Auspicious Artifacts Wholesale.” I quickly learned that the sight of foreigners is rare enough to provoke stares and requests for photographs. And ordering in the restaurants is an adventure all its own, although one menu provided heroic English translations, evidently plucked from online dictionaries: Tiger Eggs with Burning Flesh, After the Noise Subspace, Delicious Larry, Elbow Sauce. Back at my hotel, guests smoked in the hallways in their undershirts; on the street below, a rooster crowed from 3 a.m. until dawn. I could sympathize with Lin Huiyin, who complained in one letter to Wilma Fairbank that travel in rural China alternated between “heaven and hell.” (“We rejoice over all the beauty and color in art and humanity,” she wrote of the road, “and are more than often appalled and dismayed by dirt and smells of places we have to eat and sleep.”)

In the morning, I haggled with a driver to take me the last 23 miles to the Temple of Buddha’s Light. It is another small miracle that the Red Guards never made it to this lost valley, leaving the temple in much the same condition as when Liang and Lin stumbled here dust-covered on their mule litters. I found it, just as they had, bathed in crystalline sunshine among the pine trees. Across an immaculately swept courtyard, near-vertical stone stairs led up to the East Hall. At the top, I turned around and saw that the view across the mountain ranges had been totally untouched by the modern age.

In 1937, when monks heaved open the enormous wooden portals, the pair was struck by a powerful stench: The temple’s roof was covered by thousands of bats, looking, according to Liang, “like a thick spread of caviar.” The travelers gazed in rapture as they took in the Tang murals and statues that rose “like an enchanted deified forest.” But most exciting were the designs of the roof, whose intricate trusses were in the distinctive Tang style: Here was a concrete example of a style hitherto known only from paintings and literary descriptions, and whose manner of construction historians could previously only guess. Liang and Lin crawled over a layer of decaying bat corpses beneath the ceiling. They were so excited to document details such as the “crescent-moon beam,” they didn’t notice the hundreds of insect bites until later. Their most euphoric moment came when Lin Huiyin spotted lines of ink calligraphy on a rafter, and the date “The 11th year of Ta-chung, Tang Dynasty”—A.D. 857 by the Western calendar, confirming that this was the oldest wooden building ever found in China. (An older temple would be found nearby in the 1950s, but it was far more humble.) Liang raved: “The importance and unexpectedness of our find made this the happiest hours of my years of hunting for ancient architecture.”

Today, the bats have been cleared out, but the temple still has a powerful ammonia reek—the new residents being feral cats.

Liang and Lin’s discovery also had a certain ominous poignancy. When they returned to civilization, they read their first newspaper in weeks —learning to their horror that while they were enraptured in the Temple of Buddha’s Light, on July 7 the Japanese Army had attacked Beijing. It was the beginning of a long nightmare for China, and decades of personal hardship for Liang and Lin. In the agonizing years to come, they would return to this moment in Shanxi as the time of their greatest happiness.

“Liang and Lin’s generation really suffered in China,” says Hu Jingcao, director of the eight-part Chinese TV series on Liang and Lin. “In 1920s and ’30s, they led such beautiful lives, but then they were plunged into such misery.” Liang Sicheng outlived Lin by 17 years, and saw many of his dreams shattered as Beijing and many historical sites were destroyed by thoughtless development and rampaging Maoist cadres.

“How could anyone succeed at that time?” asked Hu Jingcao.

In the depths of the Sino-Japanese war in 1941, lying in her sickbed, Lin Huiyin had written a poem for an airman friend killed in combat:

Let’s not talk about who wronged you.

It was the age, hopeless, unweighable.

China has yet to move forward;

dark night

Waits its daybreak.

It could stand as an elegy for herself and her husband.

**********

Back in Beijing, I had one last pilgrimage to make. Liang and Lin’s courtyard home in the 1930s is now a site that has become a contested symbol of the pair’s complex legacy. As the world knows, the Chinese capital is one of the world’s great planning disasters. Even the better-educated taxi drivers talk with nostalgia of the plan Liang Sicheng once offered that would have made it a green, livable city. (He even wanted to turn the top of the walls into a pedestrian park, anticipating the High Line in New York by six decades.) According to activist He Shuzhong, founder of the Beijing Cultural Heritage Protection Center, the public’s new fascination with Liang and Lin reflects a growing unease that development has gone too far in destroying the past: “They had a vision of Beijing as a human-scale city,” he said, “which is now nothing but a dream.”

From the relative calm of the Peninsula Hotel near the Forbidden City, I walked for 20 minutes along an avenue of gleaming skyscrapers toward the roaring din of the Second Ring Road, built on the outline of the city walls destroyed by Mao. (On the evening before the wrecking balls arrived, Liang sat on the walls and wept.) Hidden behind a noodle bar was the entrance to one of the few remaining hutongs, or narrow lane ways, that once made Beijing such an enchanting historical bastion. (The American city planner Edmund Bacon, who spent a year working in China in the 1930s, described Old Beijing as “possibly the greatest single work of man on the face of the earth.”) Number 24 Bei Zong Bu was where Liang and Lin spent some of their happiest days, hosting salons for their haute-bohemian friends, which included the Fairbanks—discussing the latest news in European art and Chinese literature, and the gossip from Harvard Square.

The future challenges for Chinese preservationists are inscribed in the story of this site. In 2007, the ten families who occupied the mansion were moved out, and plans were made to redevelop the area. But an instant outcry led Liang and Lin’s house, although damaged, to be declared an “immovable cultural relic.” Then, in the lull before Chinese New Year in 2012, a construction company with links to the government simply moved in and destroyed the house overnight. When the company was slapped with a token $80,000 fine, outrage flooded social media sites, and even some state-owned newspapers condemned the destruction. Preservationists were at least heartened by the outcry and described it as China’s “Penn Station moment,” referring to the destruction of the New York landmark in 1966 that galvanized the U.S. preservation movement.

When I arrived at the address, it was blocked off by a high wall of corrugated iron. Two security guards eyed me suspiciously as I poked my head inside to see a construction site, where a half-built courtyard house, modeled on the ancient original, stood surrounded by rubble. In a typically surreal Chinese gesture, Liang and Lin’s home is now being recreated from plans and photographs as a simulacrum, although no official announcements have been made about its future status as a memorial.

Despite powerful obstacles, preservationists remain cautiously optimistic about the future. “Yes, many Chinese people are still indifferent to their heritage,” admits He Shuzhong. “The general public, government officials, even some university professors only want neighborhoods to be bigger, brighter, with more designer stores! But I think the worst period of destruction is over. The protests over Liang and Lin’s house show that people are valuing their heritage in a way they weren’t five years ago.”

How public concern can be translated into government policy in authoritarian China remains to be seen—the sheer amount of money behind new developments, and the levels of corruption often seem to be unstoppable—but the growing number of supporters shows that historic preservation may soon be based on more than just hope.

**********

On my return to Manhattan, Maya Lin recalled that it wasn’t until she was 21 that her father told her about her celebrated aunt. He admitted that his “adoration” of his older sister, Lin Huiyin, had made him invert the traditional Chinese favoritism for sons, and place all his hopes and attention on her. “My whole life was framed by my father’s respect for Lin Huiyin,” she marveled. The artist showed me a model for a postmodern bell tower she is designing for Shantou University, in Guangdong province, China. Whereas Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin never had the opportunity to solely design any great buildings, the newly rich China has become one of the world’s hotbeds of innovative contemporary architecture. “You could say that Lin’s passion for art and architecture flows through me,” Maya said. “Now I’m doing what she wanted to.”

Chinese Architecture: Art and Artifacts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)