Macho in Miniature

For nearly 40 years, G.I. Joe has been on America’s front lines in toy boxes from coast to coast

"Don’t you dare call G.I. Joe a doll!" Hasbro toy company president Merrill Hassenfeld charged his sales force at the 1964 Toy Fair, in New York. "If I overhear you talking to a customer about a doll, we’re not shipping any G.I. Joes to you."

G.I. Joe was a doll, of course, but Hassenfeld’s designers had done all they could to make him the toughest, most masculine doll ever produced. Ken, companion of the glamorous and by then already ubiquitous Barbie, sported Malibu shorts and a peaches-and-cream complexion. The inaugural 1964 G.I. Joe, as preserved in the Smithsonian’s social history collection at the National Museum of American History (NMAH), cuts a radically different figure. In his khaki uniform and combat boots, he stands an imposing 11 1/2 inches tall. A battle scar creases his right cheek, and an aluminum dog tag dangles from his neck. Hasbro would furnish him with M-1 rifles, machine guns, bayonets and flamethrowers—a far cry from Barbie’s purses and pearls.

While Barbie had little articulation in her limbs, G.I. Joe debuted as "America’s Moveable Fighting Man," with knees that bent and wrists that pivoted to take better aim at any enemy. "Barbie is pretty stiff, with her feet perpetually deformed into high-heeled shoes," says Barbara Clark Smith, a curator of social history at NMAH. "She’s essentially a model for viewing by others. She relates back to the historic restrictions of women’s physical movement—to corsets and long skirts. While Joe is active, Barbie is pretty inflexible, waiting to be asked to the prom."

G.I. Joe was the concept of Larry Reiner, an executive at the Ideal Toy Company, one of Hasbro’s competitors. But when Ideal balked at Reiner’s soldier-doll—as recounted in Vincent Santelmo’s Don Levine, overcame them. (As for Reiner, he never really cashed in on his idea. He signed for a flat fee, amounting to $35,000 from Hasbro, but neglected to negotiate a royalty agreement that could have earned him tens of millions.)

"When the country’s not at war," Levine told his colleagues, "military toys do very well." Ironically, G.I. Joe came out the same year—1964—that President Lyndon Johnson used the Gulf of Tonkin incident to up the ante in Vietnam. Until that war tore the country asunder, G.I. Joe thrived. Sales reached $36.5 million in 1965. That was also the year that Joe gained some black comrades in arms, although the face of the African-American G.I. Joe doll was identical to that of his white counterpart, merely painted brown. Joe got a new mission and a new uniform. The original had been modeled after the infantrymen, sailors, marines and pilots of World War II and Korea—the war of dads and granddads. In 1966, Hasbro outfitted Joe for Vietnam, giving him a green beret, an M-16 and the rocket launcher of U.S. Army Special Forces.

But according to Santelmo, orders for Joe ground to a near halt in the summer of 1968 as the little guy found himself adrift in the same hostile home front as veterans returning from Vietnam. Some consumers even called G.I. Joe’s Americanism into question. Since 1964, G.I. Joe heads had been produced in Hong Kong, then shipped to Hasbro’s U.S. plants to be fastened atop American bodies. His uniforms came from Hong Kong, Japan and Taiwan. One angry mom wrote to Hasbro to say that "the true American soldier is not outfitted with clothes made in Asia." Another, quoted in the New York Times magazine and from the other end of the political spectrum, asked, "If we’re going to have toys to teach our children about war,...why not have a G.I. Joe who bleeds when his body is punctured by shrapnel, or screams when any one of his 21 moveable parts are blown off?"

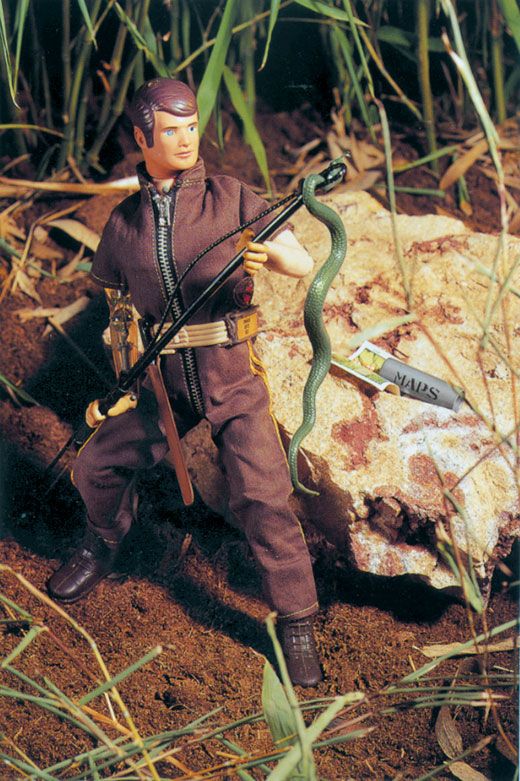

In 1967, Hasbro had introduced a talking G.I. Joe, and the doll predictably barked battle commands. In reality, however, he was not so resolute, and under continued cultural cross fire, he abandoned the battlefield entirely in 1969. Joe had begun his existence by closeting his identity as a doll; now, he would survive by stowing his uniform and becoming, in effect, the greatest draft dodger in U.S. toy history. Hasbro repackaged Joe as a freelance, civilian adventurer. As Joe drifted into the ’70s, the round "Adventure Team" medallion he wore was more peace sign than dog tag. He sprouted big fuzzy hair and a bushy beard that would never make it past a Marine barber. And he took on all sorts of trendy attributes, from a Bruce Lee-like kung fu grip to Six-Million-Dollar-Man-style bionic limbs.

On his far-flung travels away from battle zones, the AWOL soldier found new foes to fight. He did combat with giant clams, spy sharks, pygmy gorillas, massive spiders, white tigers, boa constrictors, mummies and abominable snowmen—anyone and anything, it seems, but actual U.S. military adversaries. Having conquered the natural and unnatural world, G.I. Joe found new opponents in outer space—"The Intruders," dumpy Neanderthal space aliens who looked like a race of squat Arnold Schwarzeneggers. Against them, Joe risked death by squeezing; a toggle on the Intruders’ back lifted beefy arms to ensnare the man of action in an extraterrestrial bear hug.

But if Joe got caught in the Vietnam quagmire, it was the OPEC oil embargo in 1976 that almost did him in for good. Petroleum, of course, is the major component of plastic, of which the figures, vehicles and most of G.I. Joe’s equipment were made. "As a result," writes Santelmo, "Hasbro found that it would have become economically unfeasible for the company to continue producing such large-scale action figures at a price that the public could afford." G.I. Joe shrank from almost a foot high to a mere three and three-quarter inches. Although he returned, in his pygmy incarnation, to limited military action in the early years of the Reagan administration, the downsized Joe continued to be far more preoccupied fighting amorphous enemies like Golobulus, Snow Serpent, Gnawgahyde, Dr. Mindbender and Toxo-Viper, a destroyer of the environment.

Then came the Persian Gulf War and, with it, a renewal of patriotism. And when crude oil prices dipped after that conflict, Joe swelled to his earlier size. But new antagonists included a group calling itself the Barbie Liberation Organization (BLO). In 1993, this cabal of prankish artists bought several hundred "Teen Talk" Barbies and Talking G.I. Joe Electronic Battle Command Dukes, switched their voice boxes and surreptitiously returned them to toy stores. Brushing Barbie’s long blonde hair, an unsuspecting doll owner might hear Barbie cry out: "Eat lead, Cobra," or "Attack, with heavy firepower." G.I. Joe suffered similar indignities. The BLO sent the Smithsonian a "postop" G.I. Joe, who, in his best Barbie soprano voice, warbles such memorable phrases as "Let’s plan our dream wedding," "I love to try on clothes" and "Ken’s such a dream."

In today’s patriotic climate, G.I. Joe once again stands ready to take on anything from al-Qaida to the axis of evil. A 10th Mountain Division Joe, released recently, wears the same uniform, insignia and battle gear as American troops who served in Bosnia and Afghanistan, while another Joe does duty as an Army Ranger. "Currently on the shelves you’ll find representatives of four branches of the service," says Derryl DePriest, Hasbro’s marketing director. "We bring G.I. Joe into a very realistic format—the clothing, the stitching and the shape of the helmet all pay homage [to the actual troops in the field]."

Like many toys nowadays, America’s miniature fighting man is a product of the factories of the People’s Republic of China. But no matter his size, color or country of origin, Joe’s role as political weather vane will likely continue for many a campaign to come. "Joe challenged and confirmed traditional gender roles," curator Clark Smith observes. "He challenged the preconception that boys wouldn’t play with dolls, while he clearly reinforces the notion of the man as warrior." Smith believes he will remain America’s preeminent playtime paradox. "He reflects the changing and confused thinking of what we want boys to aspire to, what we want men to be—and whether we want to admit what battles we’re really in."