Madame Yale Made a Fortune With the 19th Century’s Version of Goop

A century before today’s celebrity health gurus, an American businesswoman was a beauty with a brand

:focal(315x204:316x205)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/9f/f39f1b07-f168-424f-bae0-d72733916201/mar2020_b10_prologue.jpg)

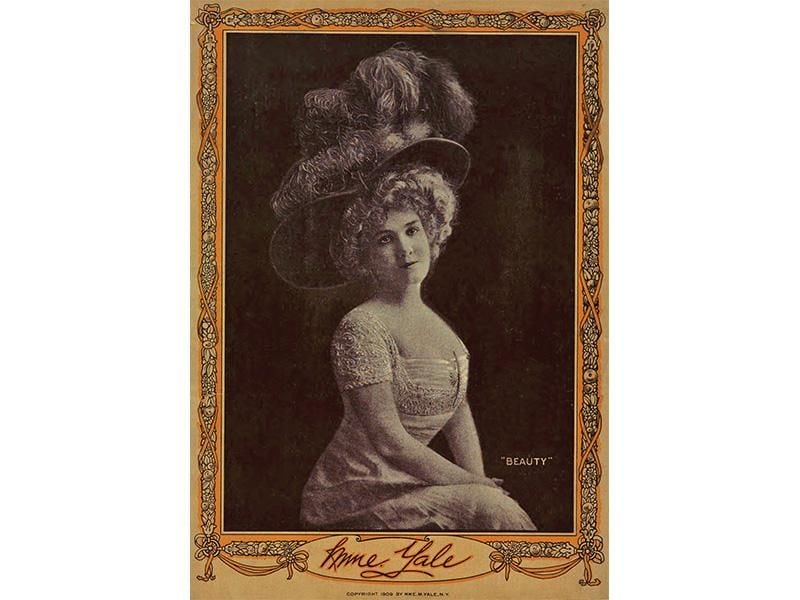

On an April afternoon in 1897, thousands of women packed the Boston Theatre to see the nation’s most beguiling female entrepreneur, a 45-year-old former homemaker whose talent for personal branding would rival that of any Instagram celebrity today. She called herself Madame Yale. Over the course of several hours and multiple outfit changes, she preached her “Religion of Beauty,” regaling the audience with tales of history’s most beautiful women, a group that included Helen of Troy, the Roman goddess Diana and, apparently, Madame Yale.

The sermon was her 11th public appearance in Boston in recent years, and it also covered the various lotions and potions—products that Yale just happened to sell—that she said had transformed her from a sallow, fat, exhausted woman into the beauty who stood on stage: her tall, hourglass figure draped at one point in cascading white silk, her blond ringlets falling around a rosy-cheeked, heart-shaped face. Applause thundered. The Boston Herald praised her “offer of Health and Beauty” in a country where “every woman wants to be well and well-looking.”

Madame Yale had been delivering “Beauty Talks” coast to coast since 1892, cannily promoting herself in ways that would be familiar to consumers in 2020. She was a true pioneer in what business gurus would call the wellness space—a roughly $4.5 trillion industry globally today—and that achievement alone should command attention. Curiously, though, she went from celebrated to infamous virtually overnight, and her story, largely overlooked by historians, is all the more captivating as a cautionary tale.

Day after day, online, in print, on TV and on social media, women are inundated with advertisements for wellness products that promise to fix our skin and our digestion and our hair and our mood seemingly at once. The (almost always) attractive women behind these products position themselves as uniquely modern innovators at the cutting edge of holistic health and beauty. But my research suggests Madame Yale, born Maude Mayberg in 1852, was using the same techniques more than a century ago. Think of her as the spiritual godmother of Gwyneth Paltrow, founder of the $250 million Goop corporation.

Like Paltrow, Madame Yale was an attractive blond white woman—“as beautiful as it is possible for a woman to be,” the New Orleans Picayune said, and the “most marvelous woman known to the Earth since Helen of Troy,” according to the Buffalo Times. Paltrow’s company markets “UMA Beauty Boosting Day Face Oil,” “GoopGlow Inside Out Glow Kit” and “G.Tox Malachite + AHA Pore Refining Tonic.” Madame Yale hawked “Skin Food,” “Elixir of Beauty” and “Yale’s Magical Secret.” Paltrow is behind a slick periodical, Goop, that is part wellness magazine and part product catalog. Madame Yale’s Guide to Beauty, first published in 1894, is a self-help book that promotes her products. Both women have aspired to an unattainable ideal of biochemical purity. Goop claims its G.Tox will “increase cell turnover and detoxify pores.” Madame Yale said her “Blood Tonic” would “drive impurities from the system as the rain drives the debris along the gutters.” And both, importantly, embodied their brands, presenting themselves as the best possible evidence of their efficacy, though Madame Yale, living in a simpler time before digital media (there are thousands of pictures of Paltrow available online), was far more explicit about it. (Goop did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Madame Yale rose to fame during a boom era for female beauty entrepreneurs, shortly before Elizabeth Arden and Estée Lauder, whose makeup empires endure today. But Madame Yale stood apart from these makeup moguls by promising to transform women from the inside out, rather than helping them hide their imperfections. That was itself an ingenious ploy: Because wearing visible makeup remained a questionable moral choice in the period, many women flocked to Yale’s product offerings, hoping to become so naturally flawless they wouldn’t need to paint their faces. In the 1890s, her business had an estimated value of $500,000—around $15 million in today’s money.

In the archives of the New Orleans Pharmacy Museum, among yellowed advertisements for cocaine-infused toothache drops and opium-soaked tampons, I found a tattered promotional pamphlet for the centerpiece of Yale’s business—Fruitcura, the product she advertised most widely. Madame Yale said she had come upon the elixir during a dark period, recalling “my cheeks were sunken, eyes hollow and vacant in expression, and my complexion was to all appearances hopelessly ruined. My suffering was almost unbearable.” She also noted that “physicians had long before pronounced me beyond their aid.” But when she imbibed Fruitcura regularly after “discovering” it at age 38, she “emerged from a life of despair into an existence of sunshine and renewed sensations of youth.” In Yale’s account, sharing Fruitcura with her “sisters in misery” (that is, selling it to them) was now her almost sacred purpose.

Her customers returned the favor, to judge from the “sincere and unsolicited” testimonials in Yale’s pamphlets. One woman wrote that she had “been a great sufferer from female trouble for over ten years, have been in an infirmary, and have been treated by some of the best physicians but received no permanent relief until I commenced to take your remedies.”

The perception that physicians were failing to help women resolve such complaints was a recurring theme for Madame Yale, as it continues to be for many wellness entrepreneurs. In the late 19th century, medical experts—almost exclusively male—were largely helpless in the face of what can only be described as an epidemic of acute unwellness among women, according to Complaints and Disorders: The Sexual Politics of Sickness, a history published by Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English in 1973. Affluent women, especially, complained of amorphous, endless malaises, fainting and finding eating untenable, losing their girlhood effervescence as they aged into marriage and childbearing. In response, doctors often attributed physical complaints to psychological ailments and declared that too much activity in a woman’s mind might lead to dysfunction in her uterus. They prescribed interminable bed rest. Today, the field of medicine has not entirely cured itself of sexism, of course. Studies have documented that diseases primarily or only affecting women (chronic fatigue syndrome, endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, fibromyalgia) receive less than their share of research funding. Likewise, physicians have tended to treat pain differently: Women are more likely than men to be prescribed sedatives instead of painkillers—a tendency that some experts interpret as a holdover from Victorian times, the old, patronizing, “You’re just being emotional” diagnosis.

When physicians don’t take women’s medical complaints at face value, entrepreneurs since Madame Yale’s time have been more than happy to. They also continue to draw a straight line between physical health and beauty, especially given that pursuing wellness is morally acceptable in a way that the single-minded pursuit of beauty—a.k.a. vanity—is not. For example, Lauren Bosworth, a blond, white woman who parlayed a reality TV career into running her own wellness company, sells supplement sets such as the “New You Kit,” which promises to support your “gut, mind, feminine health, skincare and metabolism.”

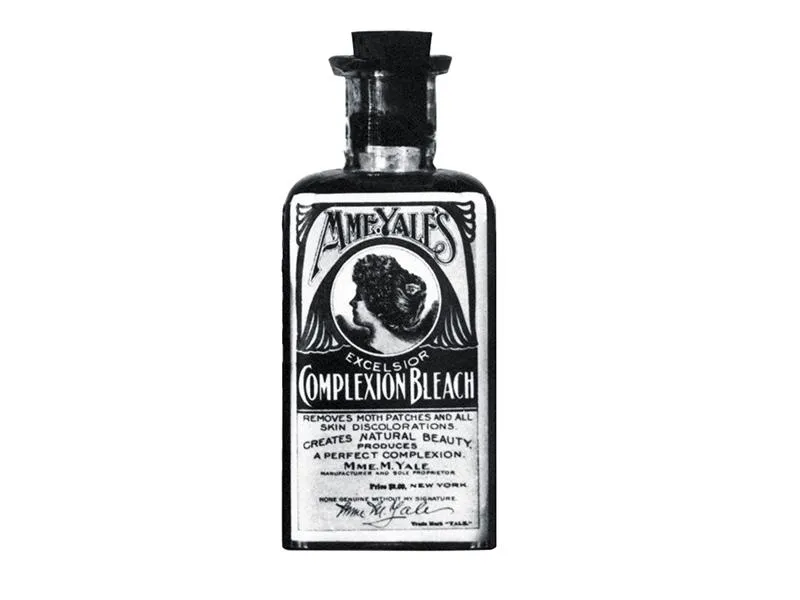

In the end, Madame Yale’s seductive sales pitch proved her downfall. The health claims she offered for her products made her vulnerable to the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act. In 1908, the U.S. government sued Madame Yale for “misbranding of drug preparations.” The feds seized more than 1,000 packages of Yale’s products and condemned them as frauds, reporting that Fruitcura was “found to consist of largely water with 16.66% alcohol by volume, 29.71% of sugar and small quantities of plant drugs.” Yale was slapped with a $500 fine and barred from selling seven of her most popular products, including Fruitcura, Blush of Youth, and Skin Food—almost a third of her total lineup.

Madame Yale’s appeal had supposedly been based on her honest relationship with women and her desire to share the secrets that had made her beautiful. Now her “magical” products were revealed as bogus, and she was exposed as a con artist. “Madame Yale’s marvelous preparations have been declared marvelous humbugs,” said the 1910 edition of the Medico-pharmaceutical Critic and Guide.

Soon Madame Yale dropped into obscurity, and may have reassumed the surname, Mayberg, that she’d shed when founding her company. Despite her two decades of fame, newspapers (which no longer benefited from her advertisements) seemed to forget about her. Today there is precious little scholarship about her, as I found in my futile search for information about her early life and later years. Given how hard she worked to craft the character of Madame Yale, I suspect she might be disappointed to learn that she is no longer remembered as a historic beauty, the way she herself once remembered Helen of Troy.

It’s tempting to think of Madame Yale as either a wellness visionary ahead of her time or a scam artist; in reality, she was both. She recognized that beautiful women are treated better than their ordinary-looking counterparts, and she gave women a nobler way to frame their pursuit of beauty. She saw an hourglass-shaped hole in the marketplace and strode boldly through it. I can’t help but admire Yale, Paltrow and Bosworth for their insight and their hustle, and I’ll even admit to making a purchase or two at the Goop online store. It’s hard to resist the allure of a beautiful woman telling me I can look and feel like her if I just click here.

Tonic Boom

Patent medicines became big business in the 19th Century. Some were bunk. Some were effective. Some are still around—Ted Scheinman

1807-37 | Healthy Profit

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/75/a175026a-7263-4aa0-a34f-fa727d363ba0/mar2020_b17_prologue.jpg)

Thomas W. Dyott was the nation’s first patent-medicine baron. In three decades he amassed a quarter-million-dollar fortune from the sale of his elixirs and lozenges.

1849-1930 | OTC Narcotic

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/37/65377f40-75c7-433d-a4f9-a4c9b6d7557f/mar2020_b05_prologue1.jpg)

It’s estimated that thousands of children died after taking this morphine-laden syrup. It wasn’t removed from shelves until 1930.

1862 | Regular Income

:focal(272x505:273x506)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/06/0a06f238-8f05-4ead-b225-b9b8e65178ea/brandethad.jpg)

Benjamin Brandreth spent around $100,000 annually advertising his Vegetable Universal Pills, marketed primarily as laxatives; from 1862 to 1883, his gross income surpassed $600,000 a year.

1875 | Long Lasting

:focal(816x956:817x957)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/eb/3e/eb3e8e4e-3c09-4e63-8c06-ddc752768ab5/mar2020_b07_prologue.jpg)

Lydia E. Pinkham introduced her Vegetable Compound, made with root and seed extracts and alcohol, for “female complaints.” A version of the herbal tonic is still produced today by Numark Brands.

1899 | Printing Money

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4d/8b/4d8bc411-623e-4e88-b3e0-6af1c2e0d15f/cheneyad.jpg)

The mogul F.J. Cheney estimated that newspapers carrying ads for patent medicines, including his, made some $20 million annually. In 1911, the government accused him of “misbranding” products.