The Man Who Sold the Eiffel Tower. Twice.

“Count” Victor Lustig was America’s greatest con man. But what was his true identity?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/f9/33f9e224-56a1-4bde-bb18-83868ed5b31f/lustig_1_resize.jpg)

The air was as crisp as a hundred dollar bill, on April 27, 1936. A southwesterly breeze filled the bright white sails of the pleasure boats sailing across the San Francisco Bay. Through the cabin window of a ferryboat, a man studied the horizon. His tired eyes were hooded, his dark hair swept backwards, his hands and feet locked in iron chains. Behind a curtain of grey mist, he caught his first dreadful glimpse of Alcatraz Island.

“Count” Victor Lustig, 46 years old at the time, was America’s most dangerous con man. In a lengthy criminal career, his sleight-of-hand tricks and get-rich-quick schemes had rocked Jazz-Era America and the rest of the world. In Paris, he had sold the Eiffel Tower in an audacious confidence game—not once, but twice. Finally, in 1935, Lustig was captured after masterminding a counterfeit banknote operation so vast that it threatened to shake confidence in the American economy. A judge in New York sentenced him to 20 years on Alcatraz.

Lustig was unlike any other inmate to arrive on the Rock. He dressed like a matinee idol, possessed a hypnotic charm, spoke five languages fluently and evaded the law like a figure from fiction. In fact, the Milwaukee Journal described him as ‘a story book character’. One Secret Service agent wrote that Lustig was “as elusive as a puff of cigarette smoke and as charming as a young girl’s dream,” while the New York Times editorialized: “He was not the hand-kissing type of bogus Count—too keen for that. Instead of theatrical, he was always the reserved, dignified noble man.”

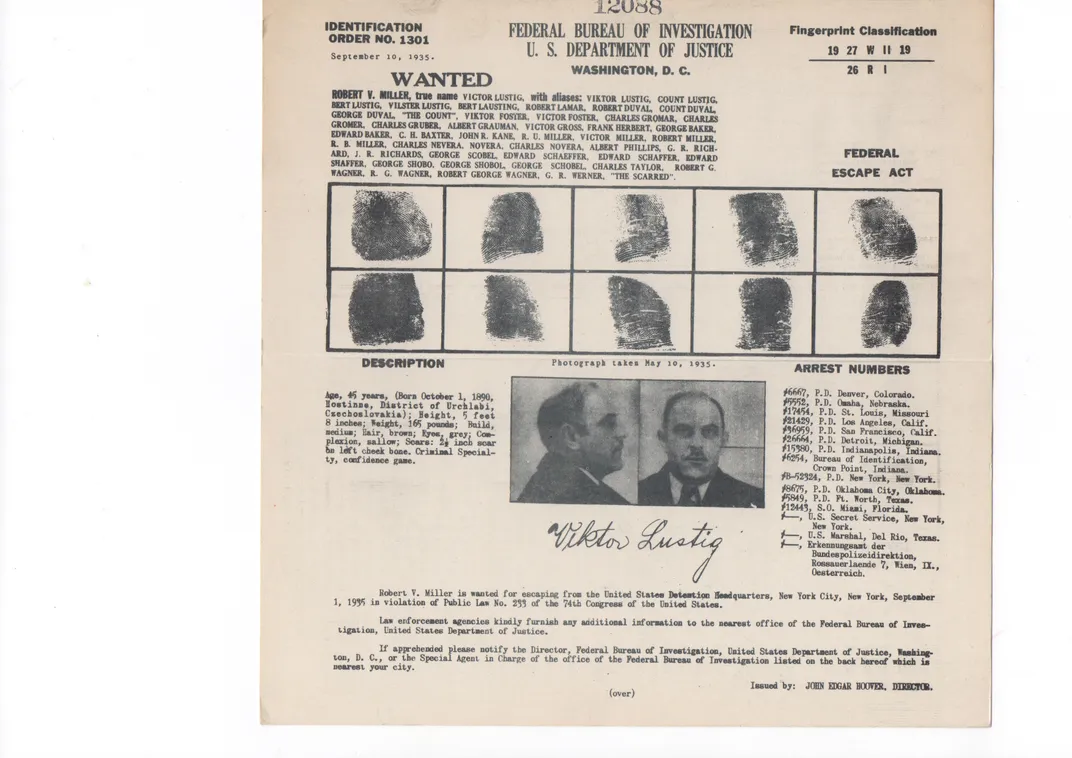

The fake title was just the tip of Lustig’s deceptions. He used 47 aliases and carried dozens of fake passports. He created a web of lies so thick that even today his true identity remains shrouded in mystery. On his Alcatraz paperwork, prison officials called him “Robert V. Miller,” which was just another of his pseudonyms. The con man had always claimed to hail from a long line of aristocrats who owned European castles, yet newly discovered documents reveal more humble beginnings.

In prison interviews, he told investigators that he was born in the Austria-Hungarian town of Hostinné on January 4, 1890. The village is arranged around a Baroque clock tower in the shadow of the Krkonoše mountains (it is now a part of the Czech Republic). During his crime spree, Lustig had boasted that his father, Ludwig, was the burgomaster, or mayor, of the town. But in recently uncovered prison papers, he describes his father and mother as the “poorest peasant people” who raised him in a grim house made from stone. Lustig claimed he stole to survive, but only from the greedy and dishonest.

More textured accounts of Lustig’s childhood can be found in various true crime magazines of the time, informed by his criminal associates and investigators. In the early 1900s, as a teenager, Lustig scampered up the criminal ladder, progressing from panhandler to pickpocket, to burglar, to street hustler. According to True Detective Mysteries magazine he perfected every card trick known: “palming, slipping cards from the deck, dealing from the bottom,” and by the time he reached adulthood, Lustig could make a deck of cards “do everything but talk.”

First-class passengers aboard transatlantic ships became his first victims. The newly rich were easy pickings. When Lustig arrived in the United States at the end of World War I, the “Roaring Twenties” were in full swing and money was changing hands at a fevered pace. Lustig quickly became known to detectives in 40 American cities as ‘the Scarred,’ thanks to a livid, two-and-a-half inch gash along his left cheekbone, a souvenir from a love rival in Paris. Yet Lustig was a considered a “smoothie” who had never held a gun, and enjoyed mounting butterflies. Records show that he was just five-foot-seven-inches tall and weighed 140 pounds.

His most successful scam was the “Rumanian money box.” It was a small box fashioned from cedar wood, with complicated rollers and brass dials. Lustig claimed the contraption could copy banknotes using “Radium.” The big show he gave to victims was sometimes aided by a sidekick named “Dapper” Dan Collins, described by the New York Times as a former ‘circus lion tamer and death-defying bicycle rider.’ Lustig’s repertoire also included fake horse race schemes, feigned seizures during business meetings, and bogus real estate investments. These capers made him a public enemy and a millionaire.

America in the 1920s was infested with such confidence rackets, operated by smooth-talking immigrants like Charles Ponzi, namesake of the “Ponzi scheme.” These European con artists were professionals who called their victims ‘marks’ instead of suckers, and who acted not like thugs, but gentlemen. According to the crime magazine True Detective, Lustig was a man who “society took by one hand, the underworld by the other…a flesh-and-blood Jekyll-Hyde.” Yet he treated all women with respect. On November 3, 1919, he married a pretty Kansan named Roberta Noret. A memoir by Lustig’s late daughter recalls how Lustig raised a secret family on whom he lavished his ill-gotten gains. The rest he spent on gambling, and on his lover, Billie Mae Scheible, the buxom owner of a million-dollar prostitution racket.

Then, in 1925, he embarked upon what swindling experts call “the big store.”

Lustig arrived in Paris in May of that year, according to the memoir of U.S. Secret Service agent James Johnson. There, Lustig commissioned stationary carrying the official French government seal. Next, he presented himself at the front desk of the Hôtel de Crillon, a stone palace on the Place de la Concorde. From there, pretending to be a French government official, Lustig wrote to the top people in the French scrap metal industry, inviting them to the hotel for a meeting.

“Because of engineering faults, costly repairs, and political problems I cannot discuss, the tearing down of the Eiffel Tower has become mandatory,” he reportedly told them in a quiet hotel room. The tower would be sold to the highest bidder, he announced. His audience was captivated, and their bids flowed in. It was a scam Lustig pulled off more than once, sources said. Amazingly, the con man liked to boast of his criminal achievements, and even penned a list of rules for would-be swindlers. They’re still circulated today:

_________________________________________

LUSTIG’S TEN COMMANDMENTS OF THE CON

1. Be a patient listener (it is this, not fast talking, that gets a con-man his coups).

2. Never look bored.

3. Wait for the other person to reveal any political opinions, then agree with them.

4. Let the other person reveal religious views, then have the same ones.

5. Hint at sex talk, but don’t follow it up unless the other fellow shows a strong interest.

6. Never discuss illness, unless some special concern is shown.

7. Never pry into a person’s personal circumstances (they’ll tell you all eventually).

8. Never boast. Just let your importance be quietly obvious.

9. Never be untidy.

10. Never get drunk.

_________________________________________

Like many career criminals, it was greed that led to Lustig’s demise. On December 11, 1928, businessman Thomas Kearns invited Lustig to his Massachusetts home to discuss an investment. Lustig crept upstairs and stole $16,000 from a drawer. Such a barefaced theft was out of character for the con man, and Kearns screamed to the police. Next, Lustig had the audacity to trick a Texas sheriff with his moneybox, and later gave him counterfeit cash, which attracted the attention of the Secret Service. “Victor Lustig was [a] top man in the modern world of crime” wrote another agent called Frank Seckler, “He was the only one I ever heard of who swindled the law.”

Yet it was Secret Service agent Peter A. Rubano who vowed to put Lustig behind bars. Rubano was a heavy-set Italian-American with a double chin, sad eyes, and endless ambition. Born and raised in the Bronx, Rubano had made his name by trapping the notorious gangster Ignazio “The Wolf” Lupo. Rubano delighted in seeing his name in the newspapers, and he would dedicate many years to catching Lustig. When the Austrian entered the counterfeit banknote business in 1930, Lustig fell under Rubano’s crosshairs.

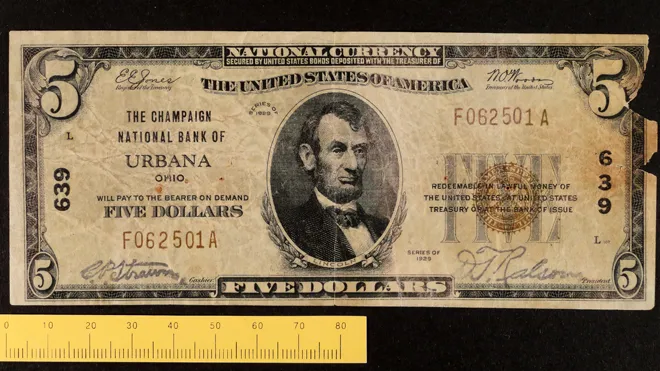

Teaming up with gangland forger William Watts, Lustig created banknotes so flawless they fooled even bank tellers. “Lustig-Watts notes were the supernotes of the era,” says Joseph Boling, chief judge of the American Numismatic Association, a specialist in authenticating notes. Lustig daringly chose to copy $100 bills, those scrutinized most by bank tellers, and became “like some other government, issuing money in rivalry with the United States Treasury,” a judge later commented. It was feared that a run of fake bills this large could wobble international confidence in the dollar.

Catching the count became a cat-and-mouse game for Rubano and the Secret Service. Lustig traveled with a trunk of disguises and could transform easily into a rabbi, a priest, a bellhop or a porter. Dressed like a baggage man, he could escape any hotel in a pinch—and even take his luggage with him. But the net was closing in.

Lustig finally felt a tug on the velvet-collar of his Chesterfield coat on a New York street corner on May 10, 1935. A voice ordered: “Hands in the air”. Lustig studied the circle of men surrounding him, and noticed Agent Rubano, who led him away in handcuffs. It was a victory for the Secret Service. But not for long.

On the Sunday before Labor Day, September 1, 1935, Lustig escaped from the ‘inescapable’ Federal Detention Center in Manhattan. He fashioned a rope from bed sheets, cut through his bars, and swung from the window like an urban Tarzan. When a group of onlookers stopped and pointed, the prisoner took a rag from his pocket and pretended to be a window cleaner. Landing on his feet, Lustig gave his audience a polite bow, and then sprinted away ‘like a deer.’ Police dashed to his cell. They discovered a handwritten note on his pillow, an extract from Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables:

He allowed himself to be led in a promise; Jean Valjean had his promise. Even to a convict, especially to a convict. It may give the convict confidence and guide him on the right path. Law was not made by God and Man can be wrong.

Lustig evaded the law until the Saturday night of September 28, 1935. In Pittsburgh, the dashing crook ducked into a waiting car on the city’s north side. Watching from a hiding position, FBI agent G. K. Firestone gave the signal to Pittsburgh Secret Service agent Fred Gruber. The two federal officers leapt into their car and gave chase.

For nine blocks their vehicles rode neck-and-neck, engines roaring. When Lustig’s driver refused to stop, the agents rammed their car into his, locking their wheels together. Sparks flew. The cars crashed to a halt. The agents pulled their service weapons and threw open the doors. According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Lustig told his captors:

“Well, boys, here I am.”

Count Victor Lustig was hauled before the judge in New York in November 1935. “His pale, lean face was a study and his tapering white hands rested on the bar before the bench,” observed a reporter from the New York Herald-Tribune. Just before sentencing, another journalist overheard a Secret Service agent tell Lustig:

“Count, you’re the smoothest con man that ever lived.”

As soon as he stepped onto Alcatraz Island, prison guards searched Lustig’s body for concealed watch springs and razor blades and hosed him down with freezing seawater. They marched him along the main corridor between the cells—known as ‘Broadway’—in his birthday suit. There was a chorus of howls, whistles, and the clanging of metal cups against bars. “He is somewhat superficially humiliated,” Lustig’s prison record said, referring to him as ‘Miller’, “he asserts that he was accused of everything in the category of crime, including the burning of Chicago.”

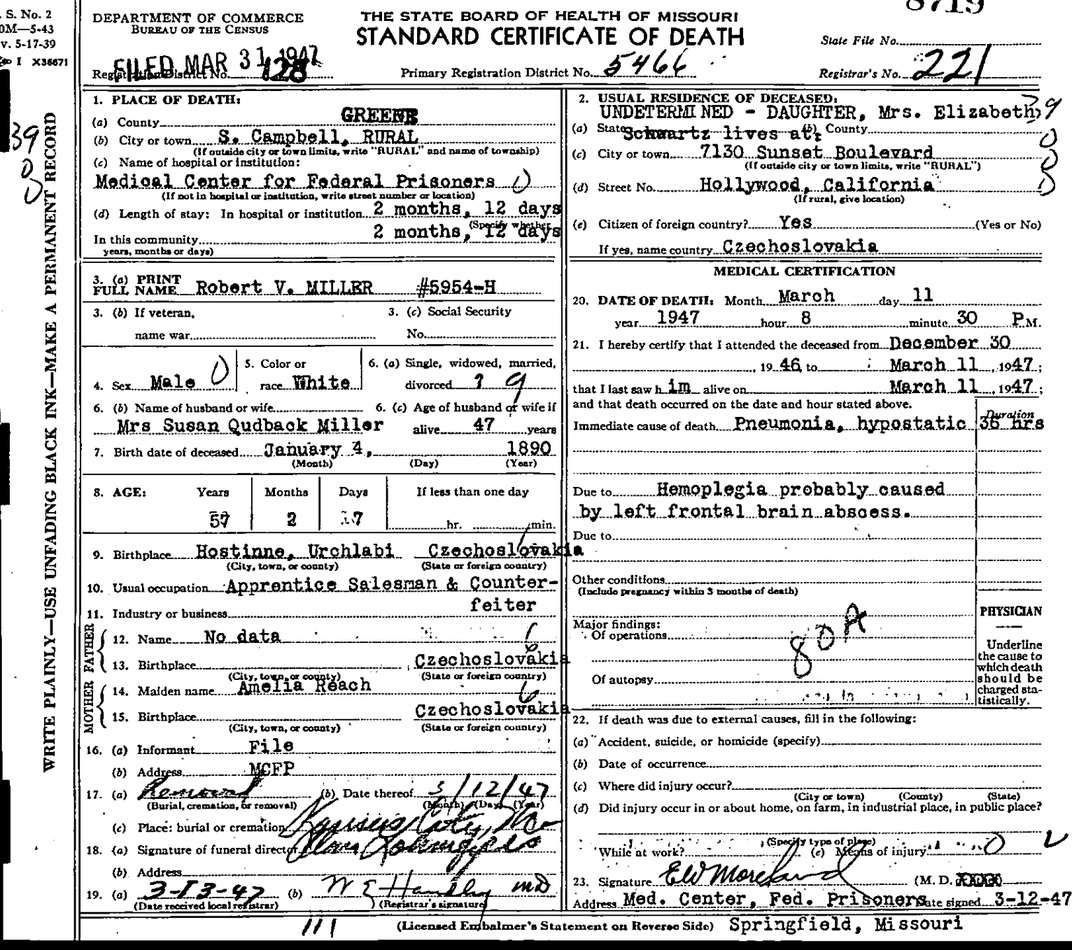

Whatever his true identity, the cold weather took its toll on prisoner #300. By December 7, 1946, Lustig had made a staggering 1,192 medical requests and filled 507 prescriptions. The prison guards believed he was faking, that his illness was part of an escape plan. They even found torn bed sheets in his cell, signs of his expert rope making. According to medical reports, Lustig was “inclined to magnify physical complaints... [and] constantly complaining of real and imaginary ills.” He was transferred to a secure medical facility in Springfield, Missouri, where doctors soon realized he was not faking. There, he died from complications arising from pneumonia.

Somehow, Lustig’s family kept his death a secret for two years, until August 31, 1949. But Lustig’s Houdini-like departure from earth was not even his greatest deception. In March of 2015, a historian named Tomáš Anděl, from Lustig’s home town of Hostinné, began a tireless search for biographical information about the town’s most famous citizen. He searched through records rescued from Nazi bonfires, pored over electoral rolls and historical documents. “He must have attended school in Hostinné,” Anděl reasoned in the Hostinné Bulletin, “yet he is not even mentioned in the list of pupils attending the local primary school.” After much searching, Anděl concluded, there is not a scrap of evidence that Lustig was ever born.

We may never know the true identity of Count Victor Lustig. But we do know for certain that the world’s most flamboyant con man died at 8:30pm on March 11, 1947. On his death certificate a clerk wrote this for his occupation:

‘Apprentice salesman.’