The Many Myths of the Term ‘Anglo-Saxon’

Two medieval scholars tackle the misuse of a phrase that was rarely used by its supposed namesakes

:focal(1292x865:1293x866)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5f/3f/5f3f62a6-2eb0-4da6-83ca-af70b8b3ef53/bayeux_tapestry_scene1_edward.jpeg)

People in the United States and Great Britain have long drawn on imagined Anglo-Saxon heritage as an exemplar of European whiteness. Before becoming president, Teddy Roosevelt led his “Rough Riders” on the 1898 U.S. invasion of Cuba with a copy of Edmond Demolins’ racist manifesto Anglo-Saxon Superiority in tow. In the 1920s, the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America lobbied in favor of segregation and argued for the exclusion of those with even a drop “of any blood other than Caucasian.” In the same time frame, a Baptist minister from Atlanta declared, “The Ku Klux Klan is not fighting anybody; it is simply pro Anglo-Saxon.” Across the Atlantic, in 1943, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill smugly inquired, “Why be apologetic about Anglo-Saxon superiority, that we were superior, that we had the common heritage which had been worked out over the centuries in England and had been perfected by our constitution?”

Today, the term “Anglo-Saxon” is little used in mainstream American circles, perhaps as a chiding WASP label directed toward northeastern elites. But as news from earlier this year has shown, it still exists as a supremacist dog whistle. Its association with whiteness has saturated our lexicon to the point that it’s often misused in political discourse and weaponized to promote far-right ideology. In April 2021, the U.S. House of Representatives’ America First Caucus published a seven-page policy platform claiming that the country’s borders and culture are “strengthened by a common respect for uniquely Anglo-Saxon political traditions.” On social media, jokes about a return to trial by combat, swordfights, thatched roofs, and other seemingly Anglo-Saxon practices quickly gained traction.

How did this obscure term—little used in the Middle Ages themselves—become a modern phrase meaning both a medieval period in early England and a euphemism for whiteness? Who were the actual people now known as the Anglo-Saxons? And what terminology should be used instead of this ahistorical title?

The Anglo-Saxon myth perpetuates a false idea of what it means to be “native” to Britain. Though the hyphenated term is sometimes used as a catchall phrase to describe the dominant tribes of early England, it’s historically inaccurate and wasn’t actually used much prior to the Norman Conquest of 1066. The name didn’t even originate in England: Instead, it first appeared on the continent, where Latin writers used it to distinguish between the Germanic Saxons of mainland Europe and the English Saxons.

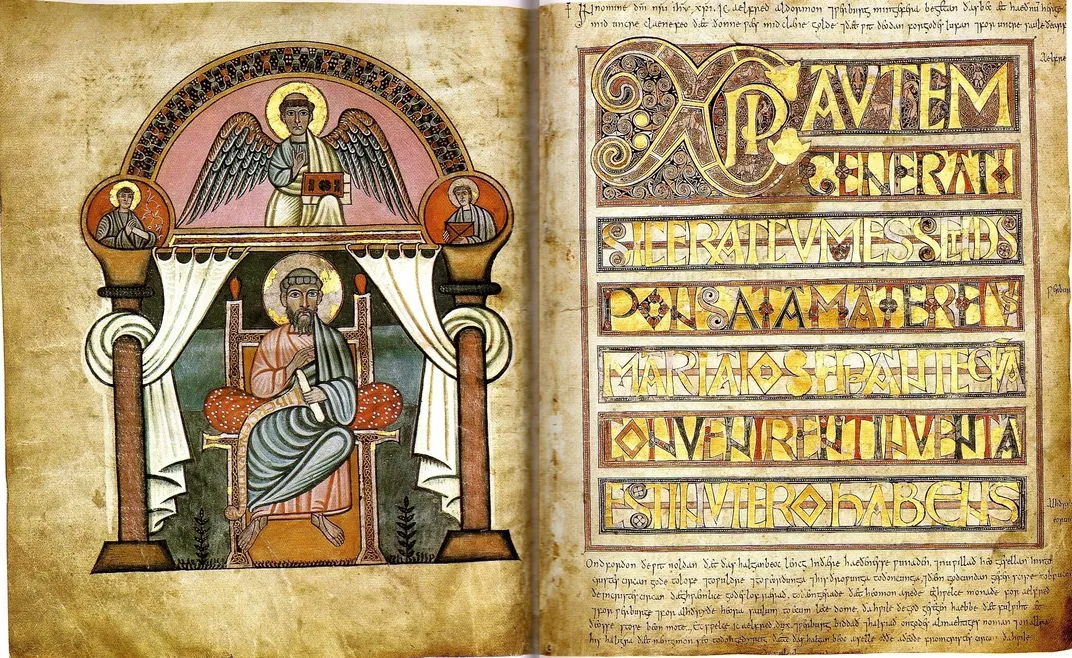

The few uses of “Anglo-Saxon” in Old English seem to be borrowed from the Latin Angli Saxones. Manuscript evidence from pre-Conquest England reveals that kings used the Latin term almost exclusively in Latin charters, legal documents and, for a brief period, in their titles, such as Anglorum Saxonum Rex, or king of the Anglo-Saxons. The references describe kings like Alfred and Edward who did not rule (nor claim to rule) all the English kingdoms. They were specifically referring to the English Saxons from the continental Saxons. Scholars have no evidence of anyone before 1066 referring to themselves as an “Anglo-Saxon” in the singular or describing their politics and traditions as “Anglo-Saxon.” While one might be king of the English-Saxons, nobody seems to have claimed to be an “English-Saxon,” in other words.

Who, then, were the groups that lend Anglo-Saxon its name? The Angles were one of the main Germanic peoples (from modern day southern Denmark and northern Germany) to settle in Great Britain. The first known mention of the Anglii was recorded by the first-century Roman historian Tacitus. Just as the Angles settled in Britain, so too did the Saxons, along with the Frisians, Jutes and other lesser-known peoples. Originally from what is now Germany, these Saxons became one of the dominant groups in Britain, though the stand-alone word Seax in Old English was not widely used and only for the Saxon groups, never for all these people together. Together, they were mostly commonly called “Englisc.”

For years, scholars of medieval history have explained that the term Anglo-Saxon has a long history of misuse, is inaccurate and is generally used in a racist context. Based on surviving texts, early inhabitants of the region more commonly called themselves englisc and angelcynn. Over the span of the early English period, from 410 A.D. (when various tribes settled on the British islands after the Romans left) to shortly after 1066, the term only appears three times in the entire corpus of Old English literature. All of these instances are in the tenth century.

Modern references to “Anglo-Saxon political traditions” would benefit from readings of actual Old English charters—early medieval documents predominantly preoccupied with land grants, writs and wills. From the eighth century onward, these charters increasingly favored granting land to laypeople, many of whom were migrants. Those Americans who seek a return to the roots of Anglo-Saxons should realize that this actually translates to more open, inclusive borders. As historian Sherif Abdelkarim writes, “[F]irst-millennium Britain offers one glimpse into the extent to which communities mixed and flourished.” Archaeological finds and historiographical sources, he adds, “suggest extensive exchange and assimilation among Britain’s inhabitants and settlers.”

One early medieval English king, Offa, minted a commemorative coin modeled on an Abbasid dinar, complete with a copy of the Islamic declaration of faith. Another king, the famed Alfred the Great, wrote in his law code that “You must not oppress foreigners and strangers, because you were once strangers in the land of Egypt.” Archaeological evidence shows that people of sub-Saharan African descent lived in early England, according to scholar Paul Edward Montgomery Ramírez.

Following centuries of disuse after the Norman Conquest, the term Anglo-Saxon reappeared in the late 16th century in antiquarian literature to refer to pre-Conquest peoples in England. Notably, as philologist David Wilton explains, the term was revived in the same period that the classification of the “Middle Ages” emerged. Essentially, he writes, “the revival of the term ‘Anglo-Saxon’ appears during a period of looking to the past to revive a national patrimony.” Between the 17th and 19th centuries, English historians were using the term as an ethnoracial identifier. The British historian Jacob Abbott, for instance, included an entire chapter on race theory in his 1862 book on ninth-century King Alfred, describing how history showed the white race’s superiority and that the medieval Alfred demonstrated that—among the white people—the modern Anglo-Saxon race was most destined for greatness. During the era of British (and later American) imperialism and colonization, this racially charged meaning became the most prominent use of the term, surpassing any historically grounded references to pre-Conquest England.

Both American and English writers have rebranded “Anglo-Saxon” to include false narratives around white racial superiority. President Thomas Jefferson perpetuated the Anglo-Saxon myth as a kind of racial prophecy of white conquest, envisioning early settlers as the continuation of their Europeans forebears. The entire settler-colonial narrative has always centered on white people migrating to the Americas just as the German tribes migrated to the British Isle. Their immigration appears natural and necessary within the larger narrative of Europe standing at the apex of civilization.

“Anglo-Saxon” subsumes all other tribes and peoples in an oversimplified way. It says nothing of Britons and others who migrated or settled in the region. This is not a heritage story grounded in facts—indeed, the myth often suspiciously erases the fact that the Angle and Saxon peoples were migrants.

The field of medieval studies has increasingly begun to discard the use of “Anglo-Saxon” in favor of more accurate, less racist terminology. More specific terms such as “Saxons,” “Angles,” or “Northumbrians” allow for greater accuracy. More broadly, terms like “early medieval English” and “insular Saxons” are used in lieu of “Anglo-Saxon.” Their own manuscripts, meanwhile most often use “Englisc” to describe themselves. As the response to the AFC statement suggests, the phrase is becoming increasingly unacceptable to the public. For many, however, it continues to evoke an imagined medieval past that justifies beliefs in white, Western superiority.

Historically speaking, the name “Anglo-Saxon” has more connection to white hoods than boar-decorated helmets. The record shows that myths about the past can be exploited to create hateful policies. But as perceptive readers, we can arm ourselves against hate by wielding historical precision as a weapon.