Why Martha Washington’s Life Is So Elusive to Historians

A gown worn by the first First Lady reveals a dimension of her nature that few have been aware of

:focal(1039x342:1040x343)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/aa/9c/aa9c365a-e52a-4399-90df-0c0cb00b5183/mar2021_b02_prologue_copy.jpg)

Ask any American what Martha Washington looked like, and you’ll hear of a kindly, plump grandmother, her neck modestly covered and her gray hair poking out of a round, frilled mob-cap, as she was portrayed in Gilbert Stuart’s 1796 portrait. Her husband explained her straightforward style in a 1790 letter: Martha’s “wishes coincide with my own as to simplicity of dress, and everything which can tend to support propriety of character without partaking of the follies of luxury and ostentation.”

Martha, then the first lady, was 65 when she sat for that famous portrait, but in earlier paintings, she is slim, her neckline plunging, décolletage on full display, her dark hair offset with a fashionable bonnet. (Make no mistake about it: Martha was considered attractive.) Her wardrobe—including custom-made slippers in purple satin with silver trimmings, which she paired with a silk dress with deep yellow brocade and rich lace on her wedding day—indicates a fashionista who embraced bold colors and sumptuous fabrics that conveyed her lofty social and economic standing. And it wasn’t just Martha, or Lady Washington as she was called: The couple’s ledgers are full of extravagant clothing purchases, for George as well.

I made use of those sources in my biography of George Washington, You Never Forget Your First, but I felt frustrated by the limited descriptions of Martha that we find in letters, and which focus almost exclusively on her role as wife, mother and enslaver. Biographers have tended to value her simply as a witness to a great man. Artists painted her according to the standards of the time, with details one would expect to see from any woman in her position—nothing particular to this woman. Indeed, Martha might be pleased by how little we know about her inner life; after George died, she burned all the letters from their 40-year marriage, although a few have been discovered stuck in the back of a desk drawer.

Historians are limited by the archives, and by ourselves. Biographers study documents to tell the story of a person’s life, using clothes and accessories to add color to their accounts. But what if we’re missing something obvious because we don’t know what to look for? Of Martha’s few surviving dresses, I’ve spent the most time looking at this one, and when I imagine Martha, I picture her in this dress. She wore it during the 1780s, a period I think of as the Washingtons’ second chance at a normal life. They were no longer royal subjects or colonists, but citizens; George was world-famous and finally satisfied with life; Martha was happily raising the young children of her late, ne’er-do-well son, John Parke Custis, as well as her nieces and nephews. They had experienced loss, triumph, life outside of Virginia, and believed, erroneously, that their life of public service had ended with the American Revolution. By the end of the decade, of course, they would become the first first family.

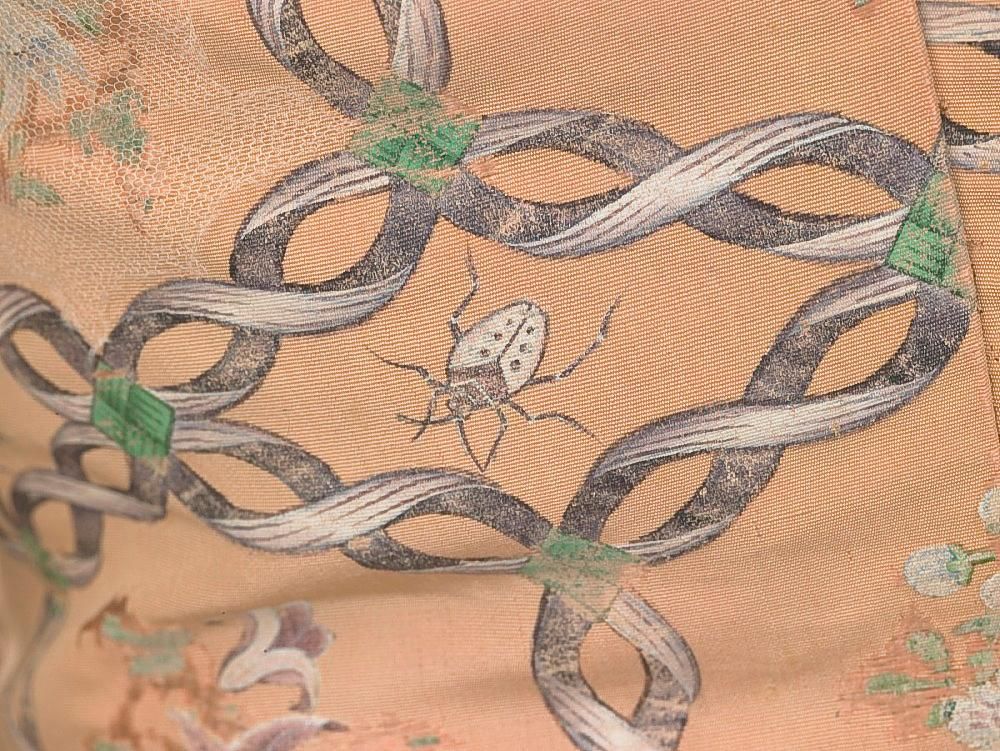

But was I seeing her clearly? The catalog entry for the dress listed the pattern I remembered, with flowers, butterflies and ladybugs—and other parts I didn’t remember. I suddenly found it odd that the 58 creatures on the dress included beetles, ants and spiders, but I didn’t know the reasons behind these images. Assuming Martha chose the pattern, it reveals something important.

Zara Anishanslin, a historian of material culture who has spent time at the Washingtons’ home at Mount Vernon as a researcher and fellow, posed an intriguing theory to me. “Martha was a naturalist,” Anishanslin explained. Or rather, Martha would have been a naturalist, had she been born a man, or in a different era; she had very few ways of expressing her passion for the natural world, which makes it easy to overlook.

As Anishanslin spoke, I was riveted—in part because, after reading every Martha Washington biography, this was the only new, original insight I’d ever come across about her, and I wondered what the best medium would be to convey this forgotten element of Martha’s life. An academic history would hardly be the best medium to spotlight objects attesting to Martha’s passion for nature; a museum exhibition would be better. If I were curating such an exhibition, I would place the dress in the largest of three glass cases, front and center. In another case, I would display the 12 seashell-patterned cushions Martha made with the help of enslaved women at Mount Vernon. In the third, I’d display 12 Months of Flowers, one of the only books from her first marriage, to Daniel Parke Custis, that she kept for personal use. The arrangement would be the first chance to see Martha’s husbands used as accessories to enhance our understanding of her. I’d call the exhibition “Don’t Be Fooled by the Bonnet.”

You Never Forget Your First: A Biography of George Washington

Alexis Coe takes a closer look at our first president—and finds he is not quite the man we remember

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.