William O’Dwyer was a decent man, or so many New Yorkers believed. After his first term as mayor of New York City, from 1945 to 1949, the Daily News called him “100 per cent honest,” while the New York Times proclaimed him to be a civic hero, alongside his predecessor, Fiorello La Guardia. A former cop turned Brooklyn prosecutor who helped send members of Murder, Inc. to the electric chair, O’Dwyer came into office facing challenges that would have made even an experienced mayor blanch—a tugboat workers strike, a looming transit strike and a shortage of city funds—and he solved them all. His landslide re-election in 1949 seemed to complete the story of the poetry-loving immigrant who arrived from Ireland with $25.35 in his pocket and became the mayor of America’s biggest and richest city.

A warmhearted man with blue-green eyes and thick graying hair, O’Dwyer soothed petitioners with a lilting Irish brogue. He was a study in contrasts: He wore white shirts with his black cop shoes, and could recite long stanzas from Yeats and Byron from memory, a New York version of Spencer Tracy’s handsome, gregarious Irish politician in The Last Hurrah (as the New York Times once noted). The mayor openly sympathized with what he called the little people. As a cop, he once shot and killed a man who raised a weapon at him; wracked with remorse, he then fed and educated the man’s son. When O’Dwyer’s wife died, after a long illness, the city mourned with him. When he met and married a fashion model from Texas named Sloane Simpson, who was more than 20 years his junior, no one begrudged the mayor his happiness. He was a surefire candidate for senator or maybe governor.

Yet only months into his second term, O’Dwyer’s reputation as a crime-fighter was coming undone. In December 1949, the Brooklyn district attorney, a squeaky-clean family man named Miles McDonald, began investigating a bookmaker named Harry Gross. In his effort to figure out how Gross could operate a $20 million betting operation without attracting the attention of law enforcement, McDonald uncovered a wide-ranging conspiracy that connected cops on the street to the highest levels of the New York City Police Department, who were connected in turn to the city’s most powerful politicians and crime bosses.

As newspaper headlines charted McDonald’s progress, more than 500 New York City policemen took early retirement rather than risk being called before the prosecutor’s grand jury. Seventy-seven officers were indicted, and the police commissioner and the chief inspector were booted from the force in a cloud of scandal and disgrace. McDonald’s investigation also zeroed in on James Moran, a silent, white-haired former cop who had accompanied O’Dwyer at every stage of his rise and now served as deputy fire commissioner. It seemed it was only a matter of time before charges would be filed against the mayor himself. Instead, at his moment of greatest peril, O’Dwyer found a protector in President Harry Truman—a man he didn’t know well, and who didn’t particularly like him. The reasons Truman protected O’Dwyer have never been adequately explained. “The O’Dwyer story is one of New York City’s more intriguing political mysteries,” Mike Wallace, the Pulitzer Prize-winning co-author of Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, told me. “It would be great to know what actually happened.”

In order to understand what happened, who William O’Dwyer was, and why Harry Truman protected him, it is necessary to re-examine what we think we know about organized crime. Cozy working relationships between urban criminal organizations, big-city labor unions and the mid-20th-century Democratic Party were first exposed by Senator Estes Kefauver’s investigations in the early 1950s, and were fleshed out a decade later by the McClellan Senate Committee and the work of U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. Yet the familiar, often weirdly romanticized tales of internecine warfare among crime families with names such as Genovese and Gambino are mostly the products of the criminal culture of the 1960s and 1970s. Though “the Mafia” as depicted by filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese was real enough, it wielded just a fraction of the power of its predecessors, which went by names like “the syndicate” or “the rackets”—and which stood with one leg in the criminal underworld and the other in the “legitimate” worlds of business and politics. It was this systemic culture of corruption that McDonald revealed, and that posed a threat large enough to be seen from the White House.

I’ve long been interested in O’Dwyer’s story. I have a beloved uncle whose father was a big shot in the syndicate run by the gangster Abner “Longie” Zwillman. My curiosity about my uncle led me to accompany him on his travels, and I have spoken at length with men who wound up living in mansions in places like West Palm Beach after making fortunes in the world of American organized crime. As a teenager interested in local New York City politics, I was also lucky to meet Paul O’Dwyer, William O’Dwyer’s brother and closest political adviser, and was charmed by his Irish brogue and passionate advocacy for social justice.

My quest to solve the mystery of William O’Dwyer’s undoing led me to old FBI files, newspaper archives and the records from McDonald’s grand jury, which were unsealed long after memories of his investigation had faded. I also found tantalizing clues in Truman’s private correspondence, which is now housed in the Truman Presidential Library in Independence, Missouri, and in the papers that J. Edgar Hoover kept in his office safe and are now stored at the National Archives facility in College Park, Maryland.

And this past June, I found myself on a train to a yacht club in Riverside, Connecticut, where I sat by the water with a spry 82-year-old attorney named Miles McDonald Jr. As we ate lunch and gazed out at nearby Tweed Island, named for the 19th-century boss of Tammany Hall, he told me about his father, a man he loved and obviously admired. Both men were lifelong Democrats and loved the ocean. Beyond that, though, he warned me that he might not have much to add to what I already knew.

“Oh, I was only 12, 13 years old then,” he said, of the time his father was investigating corruption on O’Dwyer’s watch. “The only stuff I ever saw was my dad coming home, and playing ball with me, or going sailing. He would tell me that it was important to stand up when you see something wrong—even if you are going to catch hell for it.”

* * *

As in every good tragedy, William O’Dwyer’s downfall and disgrace were occasioned by the same forces that fueled his rise. As Brooklyn’s district attorney between 1940 and 1942, O’Dwyer earned a reputation as a crime-busting hero—a brave former cop who had the courage to take on the mob. O’Dwyer prosecuted Murder, Inc. (the name was invented by the tabloids) by producing a star witness named Abe “Kid Twist” Reles, who helped send the syndicate boss Louis “Lepke” Buchalter to the electric chair at Sing Sing.

During the war, O’Dwyer was awarded a general’s star for investigating corruption in Air Force contracts. As Roosevelt’s under secretary of war Robert Patterson wrote in an internal letter, “Bill O’Dwyer, I firmly believe, has done more than anyone else to prevent fraud and scandal for the Army Air Forces.” In 1944, President Roosevelt recognized O’Dwyer’s service by appointing him as his personal representative to the War Refugee Board, a job with ambassadorial status.

It was no surprise when O’Dwyer, who ran for mayor against LaGuardia in 1941 but lost, finally recaptured New York City for the Democratic Party in 1945. As mayor, O’Dwyer charmed reporters while projecting an image of personal modesty. In a city where mob bosses like Buchalter and Frank Costello (later immortalized as Vito Corleone in The Godfather) rubbed shoulders with celebrities and politicians while ruling criminal empires from apartments on Central Park West, there was little evidence that the mayor himself was interested in ostentatious personal luxuries, according to local reporters who covered him.

Yet he proved to be quite comfortable in the role of glad-handing frontman for a network of corruption that gave the crime bosses and their political partners a stranglehold over the city’s economic life. From the waterfront docks that handled more than $7 billion a year in shipping, to the trucks that moved meat and produce to the city’s stores, to the beat cops who routinely tolerated crimes like illegal betting and prostitution, to the courts that seemed incapable of convicting the city’s most violent criminals, to the waterfront unions that forced their members to turn over as much as 40 percent of their pay, syndicates worked with the city’s political, law enforcement and union leadership for their own benefit at the expense of the city and its people.

In ways that the American public would not understand for years, such arrangements had become routine in the big Northern and Midwestern cities that formed a pillar of the national Democratic Party that Franklin Roosevelt had built, another pillar being the segregationist strongholds of the South. Labor unions, a key part of the Democratic Party base, often employed the mob as muscle, an arrangement pioneered in New York City in the 1920s by the crime boss Arnold “the Brain” Rothstein. Versions of this structure were found in other cities, too. Chicago was perhaps America’s most notorious mob-run town, the fiefdom of gangsters such as Al Capone. In Kansas City, arrangements were made by Tom Pendergast, a one-time alderman and Democratic Party chairman who ran a large-scale patronage operation, controlling elections, government contracts and more.

Nor was the spirit of cooperation between violent criminals and politicians confined to local politics. During the war, the federal government turned to crime bosses like Charles “Lucky” Luciano to ensure labor peace in factories and the docks, to root out potential spies and saboteurs, and later to help compile detailed maps of Sicily, which the Allies invaded in 1943. After the war, the mob ostensibly kept the Communists off the docks and out of the trucking companies. A thickening web of personal and institutional relationships between politicians and criminals made it hard even for people who thought of themselves as honest to see that anything was wrong.

* * *

Yet there was at least one elected Democrat in New York City who despised these arrangements and the men who made them. Miles McDonald got his start in politics as an assistant district attorney in 1940 under none other than William O’Dwyer. According to the Brooklyn Eagle reporter Ed Reid, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on the O’Dwyer scandals, one of O’Dwyer’s key criteria for hiring McDonald and other prosecutors was that they had no prior experience in criminal law. The young estates and trusts lawyer won his first case, then proceeded to lose his next 13 cases in a row. Yet McDonald grew to love the job, and he got good at it.

McDonald was a Brooklynite by birth, and in his mind the borough and the Democratic Party were inseparable. The connection between the party and his family was literally written on the street signs near his home: McDonald Avenue was named for his father, John McDonald, a party stalwart who served as chief clerk of the Surrogate’s Court. After his father died, the party had taken care of his mother. McDonald gave thanks to the Democratic Party before dinner every evening, in the fine brownstone house at 870 Carroll Street where he lived with his wife and four children and their two beagles.

McDonald was a believer in the old-fashioned virtues of loyalty and gratitude and an aficionado of puns and other forms of wordplay. He loved doing crossword puzzles, and was fascinated by the derivations of words, whose histories illuminated their usage and meaning; their meaning was the fulcrum on which the law turned and determined whether society was regulated well or poorly. In a borough known for the greed and ubiquity of its organized crime, he greatly disapproved of gambling, which he saw as a tax levied by criminals on the poor and the children of the poor. Not even friendly bets were allowed in the McDonald home.

McDonald avoided any hint of improper influence, even at the cost of seeming like a prude. When he received a gift at his office, such as Dodgers tickets, or silk ties, or liquor, from someone who wasn’t a personal friend, he had his secretary type up a letter offering the donor a choice of a local Catholic, Jewish or Protestant charity to which the gift would be sent. “Some of them, they just wanted it back!” he recalled years later, to his son, more in amusement than in outrage. When he wasn’t working, or attending communion breakfasts, he delighted in going fishing with his children and, on the Fourth of July, setting off fireworks.

Nominated by Franklin Roosevelt in 1945 to be U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York, and renominated by Truman after Roosevelt’s death, he chose instead to run for O’Dwyer’s old job as Brooklyn’s district attorney—a position with less connection to national power, but closer to the streets that he loved. O’Dwyer, then settling into his first term as mayor, could only have been pleased by McDonald’s first high-profile case, in which he successfully argued for the dismissal of an indictment of the “Black Hawk Gang” that had been brought by O’Dwyer’s successor at the district attorney’s office, George Beldock, who had run against O’Dwyer on the Republican ticket and accused him of corruption.

By early 1950, however, McDonald’s investigations were beginning to unsettle the mayor. The previous December, McDonald had begun his inquiry into the bookmaker Harry Gross by quietly extending the term of a sitting grand jury, whose work would uncover a citywide system of payoffs that amounted to more than $1 million a year. “He was a smooth, suave individual with gentlemanly manners,’’ McDonald later recalled of Gross. “He was smart as a whip. Without Harry, there was no graft.’’

The investigation of Gross’ bookmaking empire, which employed 400 bookies, runners and accountants in 35 betting parlors across the city, Long Island and northern New Jersey, led McDonald to other protection rackets, spanning city departments. Most of these roads led back to James Moran, who had kept order in the courtroom back when O’Dwyer was a local judge. When O’Dwyer was elected Brooklyn district attorney in 1939, Moran became his clerk. Eventually, Moran organized the fuel oil racket, in which building owners had to pay bribes to receive oil, and he received large, regular bribes from the head of the firemen’s union.

Now Moran, New York’s most powerful political fixer, was in danger, and the citywide network that he ran responded. City detectives gave bookmakers the license plates of McDonald’s plainclothes officers, to help them avoid detection. They also knew McDonald’s car.

“I remember he had a D.A. license plate,” Miles McDonald Jr. recalled. Miles Jr. had always taken the trolley to school, but now his father hired a driver who was a police detective and carried a gun. One day the car got a flat tire. “When the driver got out to change it,” he continued, “he takes his jacket off, and two cops come up and hassle him for having an exposed weapon.” Threats were exchanged. The message was clear: If the district attorney wasn’t interested in protecting the police, then the police might not be interested in protecting his family.

Still, McDonald refused to back off, even as Mayor O’Dwyer began to apply public pressure on his former protégé. At the funeral of John Flynn, commander of the 4th Precinct in Brooklyn, who committed suicide after McDonald called him to testify, O’Dwyer condemned McDonald’s investigation as a “witch hunt.” Six thousand uniformed police officers then symbolically turned their backs on McDonald. The next day, Flynn’s widow showed up at the courthouse in Brooklyn and denounced Miles McDonald as a murderer.

Looking through the records of McDonald’s grand jury proceedings, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that McDonald had begun drawing up his map of the corruption infecting the city while working under O’Dwyer and Moran at the Brooklyn district attorney’s office. Something about that experience clearly stuck with him. As McDonald told the New York Times many years later, looking back on his long career as a prosecutor and then as a judge, “No one has asked me to do anything that wasn’t right—except O’Dwyer.”

* * *

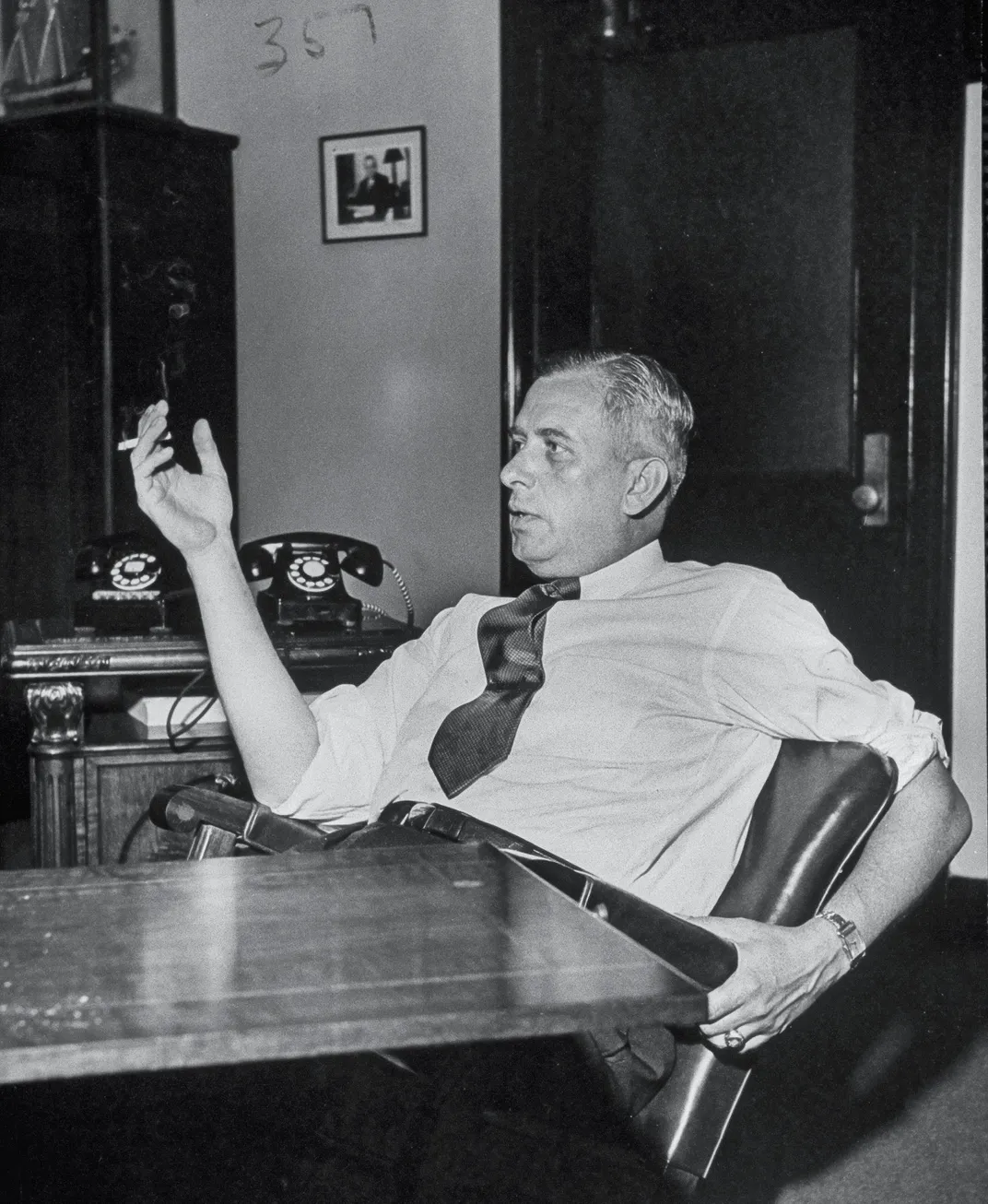

By the summer of 1950, McDonald didn’t have much time for sailing or fishing with his children at the family’s summer home on Long Island. Instead, he closeted himself in his study in Brooklyn, working all hours, lighting one cigarette with the end of another.

On July 10, 1950, Ed Flynn, the powerful Bronx Democratic committeeman, called the president with an urgent request for a meeting. No formal record of that meeting exists, but the men must have discussed what McDonald’s investigations might mean for the city, the Democratic Party—and Truman himself. Two days later, Truman met with Paul Fitzpatrick, the head of the New York State Democratic Party, and one of Flynn’s closest political associates. The following week, the president met with Eleanor Roosevelt, still a powerful player in New York’s Democratic Party, who had also urgently requested a meeting at the White House.

Truman and O’Dwyer were never close; worse, O’Dwyer had signed a telegram urging Truman not to run for re-election in 1948, predicting that the president would lose. Yet the president also had plenty to fear from a public scandal that would reveal how O’Dwyer ran New York and what such revelations would imply about urban Democratic politics across the country.

A decade earlier, Truman had barely survived the fall of his former patron, Tom Pendergast, whose control over Kansas City ended with a conviction for tax evasion in 1939 after a wide-ranging federal corruption investigation. Truman always feared the scandal would follow him to the White House, a fear that was inflamed in 1947 after FBI agents began investigating Tom Pendergast’s nephew, James Pendergast, a personal friend of Truman’s from his Army days during World War I, for vote fraud. In response, Truman’s friends in the Senate, who saw the FBI’s involvement in Kansas City politics as a not-so-veiled threat, began their own investigation of the FBI. (J. Edgar Hoover kept all five volumes of the Senate investigation’s records in his personal safe until the day he died, along with his meticulous records of other disagreements with presidents who, he felt, threatened the power of the FBI.)

What McDonald’s investigation would reveal, Flynn and Fitzpatrick knew, was that Mayor O’Dwyer was the frontman for a system of citywide corruption that was administered by Moran, the mayor’s closest political associate. Worse, they knew—as the public would find out the following August, from the public testimony of a gangster named Irving Sherman—that O’Dwyer and Moran had been meeting personally with the syndicate boss Frank Costello as far back as 1941. And as a former chairman of the Democratic National Committee, Flynn also knew that the urban political operations that had helped elect Franklin Roosevelt to the presidency four times, and Truman once, were based on a system of unsavory alliances. Putting O’Dwyer on the stand would put the Democratic Party in New York—and elsewhere—on trial. One way to keep O’Dwyer safe from McDonald’s grand jury was to get him out of the country.

On August 15, Truman appointed O’Dwyer as the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, a post from which he could not be recalled except by the president. In a private letter dated August 18, 1950, which I found in Truman’s papers, and which has never been previously reported, Paul Fitzpatrick expressed gratitude to the president for his decision. “Your recent announcement of the pending appointment of the Ambassador to Mexico, again proves to me your deep understanding of many problems and your kindness in rendering assistance,” he wrote. “May I just say thanks.”

It is impossible to say with certainty which “problems” Fitzpatrick was referring to, but clearly they were big enough to persuade the president to immediately remove the popular U.S. ambassador to Mexico, Walter Thurston, from his post and install the mayor of New York in his place. As Truman most likely saw it, by protecting O’Dwyer, he was protecting himself—as well as his party’s future. The Democratic Party, after all, had rescued the country during the Great Depression and helped save the world from Adolf Hitler, but it was able to do that only because Franklin Roosevelt had the audacity to weld together a coalition of the poor and dispossessed with progressive technocrats, white segregationists, labor unions and organized crime. Now, in the midst of the Korean War, and facing new threats from Stalin in Europe, that coalition was in danger of crumbling.

On August 24, O’Dwyer sent a personal note of thanks to Harry Truman. “The new assignment to Mexico with which you have honored me becomes increasingly important with each day,” the mayor wrote. On August 31, he resigned as mayor.

On September 15, McDonald’s investigators hit all 35 of Gross’ betting parlors in a coordinated raid. Gross himself was seized in his hotel suite.

Three days later, O’Dwyer’s nomination as ambassador to Mexico was confirmed by the Senate, with the Democratic majority steamrolling a Republican motion to delay the vote. O’Dwyer had little time to spare. On September 25, Vincent Impellitteri, the acting mayor and a Flynn ally, fired the police commissioner and replaced him with Assistant U.S. Attorney Thomas Murphy, who was fresh off his successful prosecution of the Soviet spy Alger Hiss. On September 29, Murphy replaced all 336 members of the NYPD’s plainclothes division with rookie cops. “Plainclothes Unit ‘Broken’ by Murphy to Stop Graft,” the New York Times front-page headline blared. The name of the mayor on whose watch such corruption had thrived was never mentioned in the article, nor was it mentioned in Murphy’s address to the city’s shattered police force.

Before taking up his appointment, O’Dwyer combatively denied any wrongdoing and balked at suggestions that he resigned as mayor before the Gross scandal could blow wide open. “There is no truth in that suggestion,” he told the news agency United Press. “When I left the city I had no notion or knowledge regarding the disclosures since in connection with the police department.”

But the scandal did little to buttress O’Dwyer’s reputation, and the headlines would only get worse from there.

* * *

Senator Estes Kefauver went public with his committee’s investigation of organized crime in March 1951, six months after O’Dwyer was sent to Mexico City—the first attempt at a national reckoning with what J. Edgar Hoover had stubbornly dismissed as a strictly local problem. The committee praised McDonald’s work. “Miles McDonald, district attorney of Kings County, deserves great credit for the tireless way in which he has been digging into the operations of the Gross bookmaking empire, despite repeated attempts to discourage their investigations,” the committee noted in a report. McDonald’s grand jury had proved of “great assistance to the committee in its task of following the ramifications of organized crime in interstate commerce.”

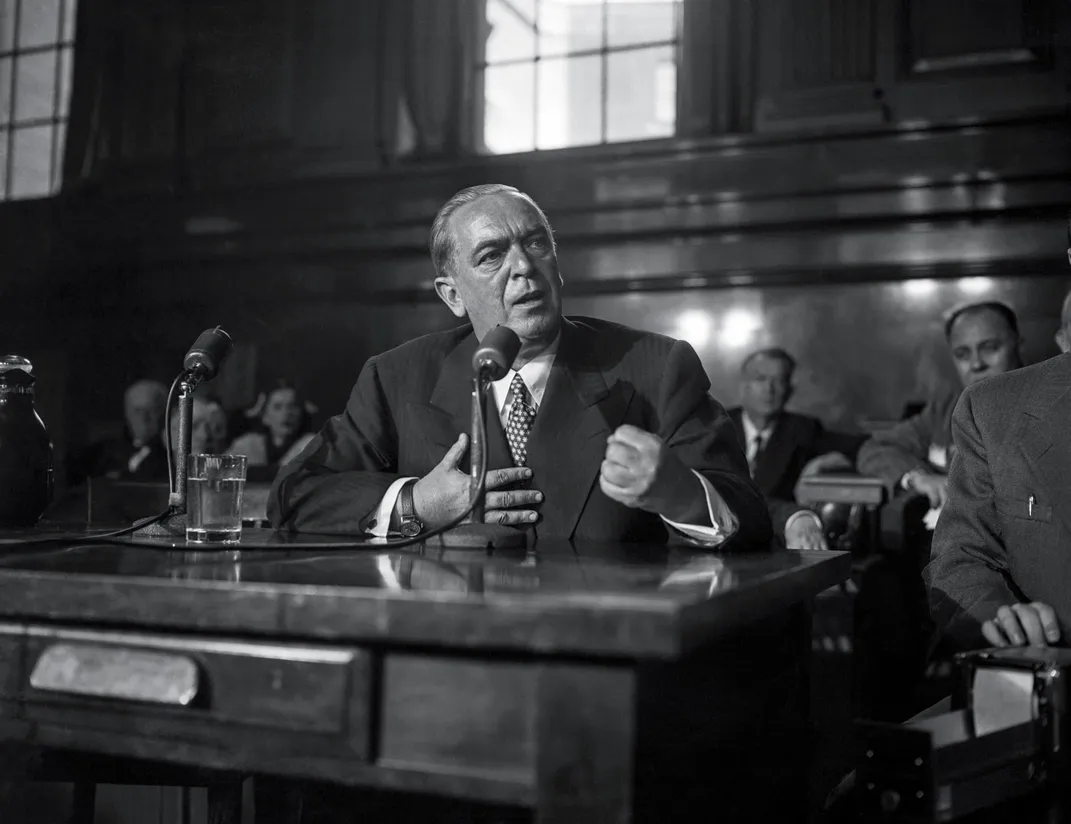

O’Dwyer returned from Mexico City to testify before the Kefauver Committee on March 19 and 20. The former mayor apologized to McDonald for calling his investigation a “witch hunt,” but he soon turned testy. When he was asked to explain a visit to Frank Costello’s Manhattan apartment in 1941, O’Dwyer told the commission, “Nothing embarrasses me that happens in Manhattan.” He was nonchalant in admitting to having appointed friends and relatives of gangsters to public offices, and was evasive or dissembling in describing how much he knew about their criminal connections. It was a performance that threw into sharp relief the extent to which O’Dwyer was a creature of a political order that seemed to him business as usual—but which had suddenly grown old.

“Mr. President,” a reporter asked Truman at his next press conference, “I wonder if you would care to comment on the testimony of former Mayor O’Dwy-er, that he appointed to office friends and relatives of gangsters?” Truman declined to comment.

“Sir, may I ask, also, is there any change contemplated in his status as ambassador?” the reporter pressed.

“No,” Truman replied.

“Mr. President, did you watch any of the hearings on television?” another reporter asked.

“No,” Truman answered. “I’ve got other things to do besides watch television.”

The effect on public opinion was immediate. The letters preserved in Truman’s files ran approximately 75 to 1 against O’Dwyer. “Has O’Dwyer something on you that you protect him this way?” asked a Manhattan dentist named Irwin Abel, who was perhaps more perceptive than even he might have imagined.

A May 1951 report by the Kefauver Committee was damning. “During Mr. O’Dwyer’s term of office as district attorney of Kings County between 1940 and 1942, and his occupancy of the mayoralty from 1946 to 1950, neither he nor his appointees took any effective action against the top echelons of the gambling, narcotics, water-front, murder, or bookmaking rackets,” the report concluded. In fact, his negligence and his defense of corrupt officials have “contributed to the growth of organized crime, racketeering, and gangsterism in New York City.”

O’Dwyer’s castle had fallen—but what crime could he be proven guilty of under the eyes of the law? Neglect? Trusting the wrong people? There was an allegation that O’Dwyer had personally accepted a bribe, after John Crane, former head of the firemen’s union, testified before the grand jury and the Kefauver Committee that he’d handed O’Dwyer an envelope filled with $10,000 at Gracie Mansion in October 1949. But O’Dwyer denied the claim, and without witnesses to corroborate it, there was no case against him. No matter. Defining “corruption” as a personal hunger for luxuries or stuffing cash in one’s pocket, as Americans often do, is to mistake the essence of the offense, which is to destroy public trust in the institutions that are supposed to keep people safe. Judged by that standard, William O’Dwyer was one of the most corrupt mayors New York City has ever seen.

In February 1952, Moran, O’Dwyer’s right-hand man, was convicted of 23 counts of extortion for his citywide shakedowns. “With this defendant,” the assistant district attorney pronounced, “public office degenerated into a racket. In the place of respect for law and order and good government, he has callously substituted cynical contempt.”

And the suggestion that O’Dwyer wasn’t personally enriched by corruption—that he was oblivious and corrupt, rather than venal and corrupt—was undermined in December 1952, after the district attorney’s office unsealed an affidavit in which O’Dwyer’s campaign manager and confidant, Jerry Finkelstein, appeared to admit before a grand jury that the former mayor had in fact received the envelope stuffed with $10,000 and delivered to him by John Crane.

Finkelstein refused to answer further questions on the matter, but O’Dwyer resigned from his ambassadorship that month, choosing to stay on in Mexico City rather than return to the city whose affections he boasted of—and to a new grand jury sniffing around the Crane incident. “I’ll be there when the Dodgers win the World Series,” he told the Washington Post columnist Drew Pearson in 1954. The Dodgers won the World Series the next year, but it would be almost a decade before O’Dwyer came home. By then, no one was paying much attention.

* * *

Before leaving office as Brooklyn district attorney in 1952 for a seat on the New York State Supreme Court, Miles McDonald made a trip to Washington to testify before another U.S. Senate committee about his investigations into organized crime. He took his son Miles Jr. with him. “I don’t know why,” his son recalled to me of that trip 70 years ago. When the hearings were done, his father took Miles Jr. to the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court. Together they gazed at the words written over the entrance: “Equal justice under the law.”

What’s amazing, in retrospect, is that it would take more than a decade for the American people to hear the whole truth about the reach of organized crime, when Joe Valachi, a Mafia turncoat, captivated and disgusted Americans in televised Senate committee hearings in September and October 1963. The hearings added momentum to U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy’s efforts to coordinate federal law enforcement against the crime syndicates, over the objections of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Within months of the Valachi hearings, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, a connection the attorney general was never able to dismiss from his mind.

Meanwhile, Miles McDonald Sr. vanished from history. He was never a publicity seeker. The reason he declined to run for governor and other high public offices, his son told me, was actually quite simple: “He said he would have been killed.”

McDonald never thought of himself as a hero. In his mind, he was a public servant. There could be no higher calling.

“The thing that I always revered, and he did too,” Miles Jr. said, “was the grand jury that sat for two years” investigating Harry Gross. “What did they get paid, $8? They were the epitome of public service. He thought so, too.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/85/6285f643-aef3-469c-b73d-c820c395b854/odwyer-opener_thumb.jpg)