Meet Grandison Harris, the Grave Robber Enslaved (and then Employed) By the Georgia Medical College

For 50 years, doctors-in-training learned anatomy from cadavers dug up by a former slave

:focal(3270x1276:3271x1277)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/e6/87e6e388-85e0-45fc-9559-826a9a0edab2/054358pu-cropped.jpg)

In the late summer of 1989, construction workers renovating a 150-year-old building in Augusta, Georgia, made a disturbing discovery. Deep in the building’s dirt basement, they found layers and layers of human bones—arms and legs, torsos and skulls, and thousands of other individual bones, scattered among remnants of nineteenth century medical tools. Many of the bones showed the marks of dissection, while others had been labeled as specimens by whomever left the bodies there. All together, the workers—and the forensic anthropology students who took over the excavation—found close to 10,000 individual human bones and bone fragments buried in the dirt.

Alarmed construction workers called the coroner’s office, but forensic officials soon figured out that the bones weren’t from any recent crime. In fact, they were a disturbing remnant from Augusta’s medical history. From 1835 until 1913, the stately brick structure on 598 Telfair Street had been home to the Medical College of Georgia, where students dissected cadavers as part of their training. During those years, freelance graverobbers—and at least one full-time employee—illegally unearthed corpses from graveyards and brought them to the school’s labs, where the bodies were preserved in whiskey before being dissected by the students. Afterward, some of the remains were converted into treasures for the school’s anatomical collection, while others were dumped into the basement and covered in quicklime to hide the stench.

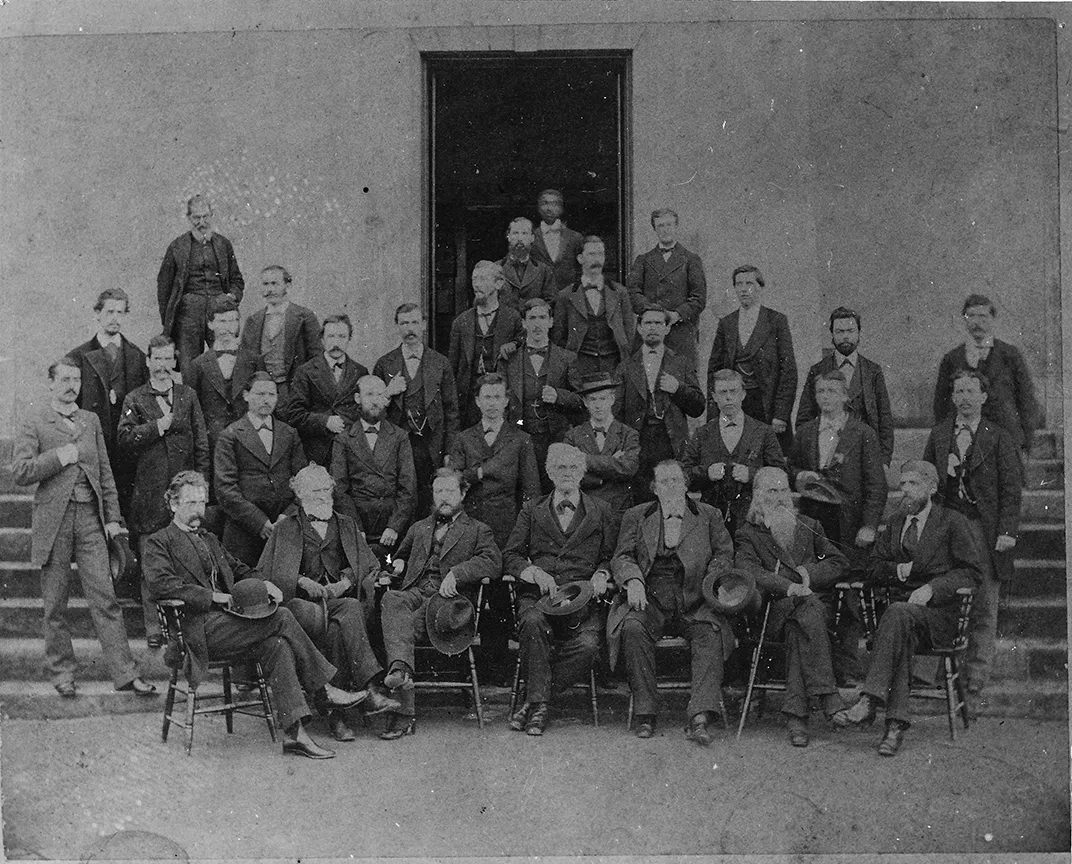

One man in particular was responsible for the bodies in the basement. For more than 50 years, first as a slave and then as an employee, Grandison Harris robbed graves to supply the medical students of Georgia with their cadavers. Like his colleagues in 18th- and 19th-century Britain, Harris was called a “resurrection man,” although his official title at the college was porter and janitor. Described as a large and powerful Gullah slave, he was purchased on a Charleston, South Carolina, auction block in 1852, and owned jointly by all seven members of the school’s medical faculty. Although grave-robbing and human dissection were illegal in Georgia for much of the 19th century (unless the cadaver was from an executed criminal), Harris’ slave status protected him from arrest. His employers, some of the most esteemed men in the city, weren’t about to be arrested either.

Harris was taught to read and write (illegal for slaves at the time), so that he could monitor the local funeral announcements, and trained his memory to mentally capture the flower arrangements on a grave so that he could recreate them perfectly after his midnight expeditions. He preferred to work in Cedar Grove cemetery, reserved for Augusta’s impoverished and black residents, where there was no fence, and where poor blacks were buried in plain pine coffins sometimes called “toothpicks.” His routine at Cedar Grove was simple: entering late at night, he would dig down to the upper end of a fresh grave, smash the surface of the coffin with an ax, reach in, and haul the body out. Then he would toss the body into a sack and a waiting wagon and cover up his work before setting off for the school, the corpse destined for vats of whiskey and, later, the student’s knives.

The students at the Medical College of Georgia liked Harris, and not just because he was doing their dirty work. In addition to getting cadavers, Harris became a de facto teaching assistant who helped out during the dissections. Reportedly, students often felt more comfortable with him than with their professors. But college students being what they are, the kids also played pranks. The school’s former dean Dr. Eugene Murphy told how, after one nighttime run, Harris went from the graveyard to a saloon for a little refreshment. Two students who had been watching Harris walked over to his wagon and pulled a corpse from a sack. One of the students—presumably the braver of the two—then climbed in the sack himself. When Harris returned, the student moaned, “Grandison, Grandison, I’m cold! Buy me a drink!” Grandison replied: “You can buy you own damn drink, I’m getting out of here!”

However friendly their relationship, there was one thing the students wouldn’t let their bodysnatcher forget. When the Civil War ended, a newly free Harris moved across the Savannah River to the tiny town of Hamburg, South Carolina, where he became a judge. But after Reconstruction failed and Jim Crow became the de facto law of the South, Harris returned to the dissection labs as a full-time employee amid race riots in Hamburg. The students saw his former position in a carpetbagger regime as disloyal to the South, and thereafter, derisively called him “judge,” perhaps to remind him of his ill-fated attempt at joining the professional class.

Harris occupied a conflicted place in his community. He was powerful: he could read and write, had a secure job, wore “proper” gentleman's clothing (a panama straw hat in summer, a derby in the winter, and always a boutonnière in his lapel on Sunday). Members of Augusta’s black community say he threw great parties, attended by the elite of local black society. And he was a member of the influential Colored Knights of Pythias, a masonic secret society started in 1880 by light-skinned blacks who borrowed the rituals of the white Knights of Pythias order. At the same time, he wasn’t exactly beloved by local blacks. In a chapter on Harris in the 1997 book Bones in the Basement: Postmortem Racism in Nineteenth-Century Medical Training, Tanya Telfair Sharpe reports that J. Phillip Waring, retired administrator of the Urban League, said “[Local blacks] feared him because they did not know who he was going to dig up next… he was feared in the, I don’t want to say supernatural, but anyone who goes out and digs up bodies and gets away with it and makes money and the medical college promoted him and what have you … what kind of person was this?” Ultimately, he proved to be a liminal figure, striding the worlds of black and white, respectable and outcast, night and day, living and dead.

In 1887, Georgia passed a law that was intended to provide a steady stream of unclaimed bodies to state medical schools; it could have destroyed Harris’ career. But the law didn’t produce as many bodies as needed, and so Harris’ services continued. He not only robbed graves, but helped purchase cadavers of the poor who died in prisons, hospitals, and elsewhere. As Grandison aged, his son George took on more of his responsibilities, although Harris the younger proved considerable less responsible and well-liked than his father. By 1904, the lab had started to emit a filthy odor, and the Board of Health conducted an investigation. Inspectors reported tobacco droppings all over the floor, alongside scraps from dissection, old rags, and a neglected vat full of bones. The following year, the university gave Harris a pension and replaced him with his son. In 1908, Grandison returned to the school for a last lecture, instructing the students on the finer points of grave-robbing.

Harris died in 1911 and was buried in Cedar Grove, the same cemetery he used to rob. In 1929, all of the cemetery’s records from the cemetery were destroyed when the Savannah River overflowed. No one knows where Harris’ body lies. As for those bones found in the basement, in 1998 they were finally buried in Cedar Grove too. There are no names on their grave, just a stone monument that says: “Known but to God.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/0c/7a0c6b18-ef63-41cc-a50b-50e5f66ecd3d/1880.jpg)