The Screenwriting Mystic Who Wanted to Be the American Führer

William Dudley Pelley and his Silver Shirts were just one of many Nazi-sympathizers operating in the United States in the 1930s

:focal(472x229:473x230)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/92/f9/92f96a02-b505-4fcb-8583-d6abe2b8d2f9/gettyimages-515136988-web.jpg)

When Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany in January 1933, an American named William Dudley Pelley believed the Führer’s rise was the fulfillment of a prophecy revealed to him by the spirit world in 1929. It was a sign, he thought, ushering in his own ascent to power, and he announced the creation of the Silver Legion, a Christian militia dedicated to the spiritual and political renewal of the United States. Jesus, Pelley reported, even dropped a line to say he approved of the plan.

That was the beginning of the group that a Congressional committee would later characterize as “probably the largest, best financed and best publicized” Nazi-copycats in the United States (Nazi Germany chose to keep Pelley and his spirits at arm’s length). A former novelist and Hollywood screenwriter who had begun publishing mystical and spiritual writings in the 1920s, Pelley dubbed himself "The Chief" of the group that became known as the Silver Shirts, due to the shimmery gray-and-blue uniforms with giant red “L”s embroidered over the heart that Pelley, a student of Hollywood pizzaz, designed himself.

Pelley’s goal was to eventually take power and implement a plan he called “Christian Economics in the United States,” a scheme he claimed was neither communist, fascist or capitalist, in which all property was owned by the state and where white citizens received “shares” based on their loyalty that guaranteed an income. African-Americans would be re-enslaved and Jews would be excluded from the nation. At the top would be “The Chief,” in emulation of Pelley’s idol Adolf Hitler.

While his ideas, steeped in spiritualism and racial theory, were never that popular—historians estimate the Silver Shirts maxed out at a membership of 15,000—Pelley wasn’t alone in admiring Hitler or the economic turnaround of 1930s Germany. The decade running up to the war found members of both the Democrats and Republicans arguing against involvement in the festering conflict in Europe. American isolationists feared a repeat of the mass casualties of World War I. Many in the business community sought to protect their investments in the European markets. And some Americans even spread German propaganda, actively spied for the Third Reich, and went so far as to advocate fascism and anti-Semitism in the United States.

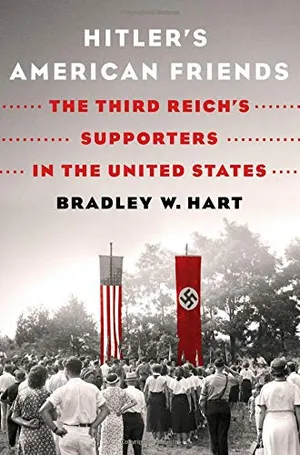

Those Americans are the subject that Fresno State University historian Bradley W. Hart explores in his new book, Hitler’s American Friends: The Third Reich’s Supporters in the United States.

Hitler's American Friends: The Third Reich's Supporters in the United States

A book examining the strange terrain of Nazi sympathizers, nonintervention campaigners and other voices in America who advocated on behalf of Nazi Germany in the years before World War II.

The Silver Shirts were just one organization that thought Nazism could translate to American politics. The German American Bund was the largest pro-Nazi organization, tallying about 30,000 members at one point. The group supported the Nazi regime and practiced its own version of American Nazism, including fielding paramilitary units armed with clubs and costuming its members in uniforms and swastika armbands. It was large enough to run several summer camps for American Nazi youth and even sent its best and brightest to Germany for indoctrination. In 1939, the organization held a 20,000-person rally at Madison Square Garden under a giant banner of George Washington flanked by swastikas, and roughed up a Jewish protestor who rushed the stage, manhandling him and ripping off his pants. Soon after, however, corruption scandals took down the Bund.

One of the most influential Nazi defenders didn’t start out as a champion of the Third Reich. When Father Charles Coughlin, a Canadian Catholic priest based in the Detroit suburb of Royal Oaks, began his local radio show in 1926, its focus was on religion and fighting the growing influence of the Ku Klux Klan. But over the course of the Great Depression, Coughlin grew more and more political—and popular, advocating economic and political schemes straight from Hitler’s playbook, including the boycott of Jewish businesses. He directly praised the Führer to millions of American listeners before church authorities shut him down. “There are few forces more powerful than religion, and [Coughlin and other right-wing preachers] used their authority to convert Americans to a prejudicial and hateful ideology,” Hart writes. “It is telling that the German government viewed these men as key propaganda assets in the United States and were reluctant to give them direct aid only because it might make them less effective in spreading pro-Nazi ideas.”

Hart details others who knowingly or unknowingly aided Hitler, including two isolationist senators (Ernest Lundeen of Minnesota and Burton Wheeler of Montana) who fell under the sway of a propagandist on the German payroll, an American businessman who made millions funneling oil from Mexico to the Germans, and American students groomed to spread pro-German ideas on college campuses.

While most pro-Nazi groups were on the fringes of public life, they created an atmosphere of uncertainty in a country where the Depression had called into question the virtues of capitalism and democracy. “Most Americans would have been aware of these groups simply because of the amount of newspaper reporting done on them,” Hart says. “Not a lot were joining these groups, but there was certainly a great deal of public debate about them and what we could or should do about them.”

None of these sympathizers, however, were quite as curious as Pelley’s Silver Shirts. Born in 1890 and the son of Methodist minister in Massachusetts, Pelley was a voracious reader and writer and began publishing his own journal at the age of 19, developing ideas about how Christianity would have to morph if it were to survive in the modern world. He went on to become a fiction writer and journalist, spending time in Siberia covering the Bolshevik revolution, where he developed strong opinions about Communists and Jews. In the 1920s, he enjoyed some success in Hollywood, working on two dozen movie scripts and saving a little money. At just 37, he retired from the film business, believing a Jewish conspiracy had targeted him.

The following year, he began having his mystical visions, in which he spoke with spirits and communicated with Jesus Christ. Pelley wrote books and journals about his experiences, and, by 1931, had enough of a following that he moved to Asheville, North Carolina, and opened his own college and publishing company. Hart says it’s difficult to tell how seriously Pelley took his own New Age ideas, but thousands of people did trust his visions.

After incorporating the Silver Shirts in 1933, he ran into trouble in North Carolina, where he was convicted of defrauding shareholders of his press the following year, landing himself on parole, a problem that would come to haunt him. His movement grew in popularity, especially in the Pacific Northwest, and in 1936, he ran for president. Though he was only successful on getting on the ballot in Washington state and drew just a handful of votes, he continued to attract followers. “He had this element of Hollywood theatricality. He was an incredibly striking figure, with the well-manicured graying goatee and the perfect Hollywood hair, smoking a pipe when he was on Capitol Hill,” says Hart. “This is a guy who knows how to cut a very powerful public image.”

In 1938, the Legion began a big membership push and started showing signs that it was moving towards violence. Pelley reportedly began traveling with 40 armed bodyguards, and members were advised to keep sawed-off shotguns and 2,000 rounds of ammunition in their homes to protect “white, Christian America.” His followers even began constructing a self-sustaining compound called Murphy Ranch in present day Will Rogers State Park outside Los Angeles that would serve as the base of pro-Nazi operations in the U.S.

“He’s a particularly scary figure for most Americans because he openly seems to be embracing violence,” Hart says. “In interviews, his followers are advising member to carry guns, and he walks around with armed bodyguards. Even if this guy is a lunatic he’s putting on the impression that he’s someone not to be messed with, which makes him uniquely resonant.”

The increasing prominence of the Silver Shirts, in the press of the day if not in membership numbers, eventually caught the eye of the federal government, and even Roosevelt began asking what could be done about Pelley. In 1939, the Dies Committee, a congressional body that investigated communist agitators and Nazi sympathizers (including the Bund), turned its attention to Pelley’s group. A violation of the terms of his parole in North Carolina served as the pretext to investigate the group’s headquarters; Pelley hid out with the Klan in Indiana to avoid facing possible prison time. A government infiltrator also testified to the Dies Committee that she had heard Pelley claiming that he would eventually be “dictator of the United States,” and that he wanted to implement the “Hitler program.” Pelley felt the walls closing in on him.

In his typical slick style, instead of having his organization broken up by the government, Pelley told his followers that the Dies Committee was doing such a great job rounding up communists and other elements of the “alien menace” that the Silver Legion no longer needed to exist. He disbanded the group, but when the war began, he was still put on trial in North Carolina for publishing a seditious magazine and sentenced to 15 years in prison. He secured an early release from prison in 1950 and started publishing about spiritualism and the occult again, espousing a philosophy called SoulCraft and writing theories about U.F.O.s, all of which still have followers today.

Hart believes that the United States was lucky that its political parties at the time policed the extremists within their ranks and that the advent of war more or less shut down any pro-Hitler rhetoric, but that wasn’t inevitable. If the Depression had dragged on or if the United States sat out the war, the extremism bubbling beneath the surface may have become more organized and powerful. By 1940, many Coughlinites, Bundists along with more mainstream isolationists, anti-war activists and others coalesced into the America First! movement, which had a burst of popularity before it went down in flames when its most famous member, aviator Charles Lindbergh, gave a brazenly anti-Semitic speech in September 1941, just a few months before Pearl Harbor.

“We need to take a new perspective on this period. It was much more ideologically divided than we remember,” says Hart. “The outcome that happened in 1945 was in no way preordained. Had Pearl Harbor not happened, [Ameican Nazism] would have gone on for quite some time. We have to realize we’re not immune to political extremism or extremist pressure groups.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.