During the Mexican-American War, Irish-Americans Fought for Mexico in the ‘Saint Patrick’s Battalion’

Anti-Catholic sentiment in the States gave men like John Riley little reason to continue to pay allegiance to the stars and stripes

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ac/d1/acd1dac7-f27f-4875-8605-5585278eaace/gettyimages-79858530_resize.jpg)

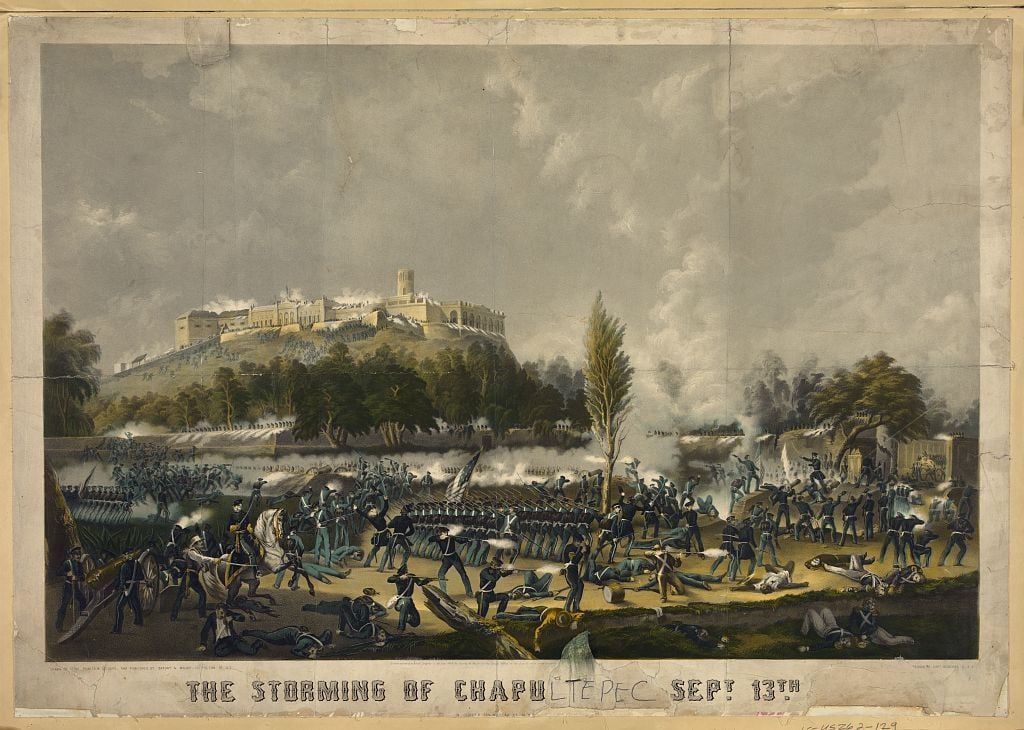

As dawn broke on the morning of September 13, 1847, a group of men stood on hastily erected gallows, nooses secured around their necks. In the distance, they watched as the relentless artillery bombardment rained down on Mexican troops at Chapultepec Castle, home to a military academy and site of the penultimate major battle in the war between Mexico and the United States. In the days prior, other members of their battalion had been publicly whipped, branded and hanged; theirs was to be yet another grisly spectacle of revenge. The last thing they witnessed was U.S. soldiers storming the desperately guarded structure on the horizon. The American colonel overseeing their execution pointed at the castle, reminding the men that their lives would extend only as long as it took for their death to come at the most humiliating moment possible. As the U.S. flag was raised at approximately 9:30 a.m., the condemned men were “launched into eternity,” as newspapers would later relay to readers in the United States.

The men who died that day were not ordinary enemy fighters. They were captured soldiers from El Batallón de San Patricio, or the Saint Patrick’s Battalion, who had fought fiercely in the Battle of Churubusco just weeks earlier. Many were Irish immigrants who had come to the United States to escape economic hardship, but found themselves fighting in the Mexican-American War against their adopted country. The conflict pitted many Catholic immigrants to America against a largely Catholic Mexico and these soldiers had switched sides, joining Mexican forces in the fight against the United States. They were, for the most, part die-hard believers in the cause around which they had coalesced—defending Mexico—until those very last moments on that September morning. Though they were on the losing side of the war, their actions are still celebrated in Mexico today, where they are viewed as heroes.

John Riley, an Irish immigrant who once trained West Point cadets in artillery, was the founding member, along with a handful of others who would later join him, of the San Patricios. When U.S. troops had arrived in Texas during the spring of 1846 ahead of a formal declaration of war, he crossed his own proverbial Rubicon—the Rio Grande River—and offered his services to the Mexican military.

The Mexican-American War began at a time when attitudes in the U.S. toward Irish and other immigrants were tinged with racial and religious prejudice. Though a massive influx was spurred by the Irish potato famine starting in 1845, the years leading up to the war had seen a steady stream of Irish immigrants to the United States seeking economic opportunity. The American Protestant majority resented the Irish for being of lower socioeconomic status, and also for being Catholic. At the time Catholicism was viewed with suspicion and at times outright hostility. These attitudes sometimes manifested in violence, including the destruction of Catholic churches in Philadelphia in what came to be known as the Bible Riots of 1844. A decade earlier, an angry mob burned down a convent on the outskirts of Boston. Between these flare-ups a general disdain for Catholic immigrants festered as the number of overall immigrants from European countries rose.

Meanwhile, settlers in Texas, which had declared itself an independent republic after a series of clashes with Mexico and had become an independent nation in 1836, were now seeking annexation by the United States. This complemented James K. Polk’s broader desire to fulfill a sense of westward expansion, which many considered the young nation’s Manifest Destiny. But the political debate over whether to bring Texas into the Union was consumed by concerns over admitting another slave state and tipping the balance, a tension that portended the Civil War to come (slavery was outlawed in Mexico in 1829, a fact many settlers in Texas disregarded).

President Polk’s persistent prodding of Congress finally resulted in a declaration of war on May 12, 1846. Ulysses S. Grant, then a young lieutenant, would later describe in his memoirs that among those gathered along the Rio Grande in the spring of 1846, “the officers of the army were indifferent whether the annexation was consummated or not; but not so all of them. For myself, I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger nation against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territories.”

Upon the declaration of war against Mexico, Congress authorized the addition of up to 50,000 new troops to bolster a fairly small standing army. The United States entered the war with an army that was comprised of 40 percent immigrants, many of whom were poorer and less educated than the officers overseeing them. Yet another stark difference between them was religion, and their treatment fueled a sense of indignation. “The officer class was not immune to religious bias,” Amy S. Greenberg, author of A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico, writes in an email. “Almost all officers were Protestants, and they not only refused to let Catholic soldiers attend mass in Mexican churches, they quite often forced them to attend Protestant services.”

The establishment of the San Patricios, then, “took place in a climate of anti-Irish and anti-Catholic prejudice during a period in the United States of unprecedented Irish immigration…the character of the Battalion was formed in the crucible of this burning conflict,” writes Michael Hogan in The Irish Soldiers of Mexico.

This was not lost on Mexico: General Antonio López de Santa Anna (known for his recapture of the Alamo in 1836) exploited this, hoping to tap into the sentiment of others like Riley. In a declaration later translated in American newspapers, he wrote, “The Mexican nation only looks upon you as some deceived foreigners, and hereby stretch out to you a friendly hand, offer you the felicity and fertility of their territory.”

He offered monetary incentives, land and the ability to retain rank and remain cohesive with their commanders, but, most ardently of all, Santa Anna appealed to their shared Catholicism. “Can you fight by the side of those who put fire to your temples in Boston and Philadelphia?... If you are Catholics, the same as we, if you follow the doctrines of our Saviour, why are you seen, sword in hand, murdering your brethren, why are you the antagonists of those who defend their country and your own God?” Instead, he promised those who fought with them would be “received under the laws of that truly Christian hospitality and good faith which Irish guests are entitled to expect and obtain from a Catholic nation.”

Though the San Patricios’ name indicated a strong Irish identity, it was in fact comprised of several nationalities of European immigrants. “They were really a Catholic battalion made up of Catholic immigrants from various countries. Many of the men were German Catholics,” says Greenberg. Nonetheless the Irish identity took hold and became the emblem of a cohesive unit throughout the war and carried over to their historical legacy. According to descriptions carried in contemporary newspapers, the San Patricios adopted a “banner of green silk, and one side is a harp, surrounded by the Mexican coat of arms, with a scroll on which is painted ‘Libertad por la Republica de Mexicana’ underneath the harp, is the motto ‘Erin go Bragh,’ on the other side is a painting of a badly executed figure, made to represent St. Patrick, in his left hand a key, and in his right a crook of staff resting upon a serpent. Underneath is painted ‘San Patricio.’”

As the war progressed, the San Patricios’ ranks grew to an estimated 200 men. The Battle of Monterrey in September of 1846, which included fighting at the city’s cathedral may have fueled new desertions. “It was apparent to most contemporary observers that the wholesale slaughter of civilians by the Texans and other volunteers, the firing on the Cathedral, and the threat to kill more civilians if the city was not surrendered, motivated many of these men,” writes Hogan. “Anti-Catholic feelings were rampant among the volunteers and now the Irish soldiers had seen it at its worst.”

But despite their committed ranks, the tide of war was not in their favor. Mexico sustained losses in subsequent major battles, including Buena Vista in February of 1847 and Cerro Gordo in April, which enabled the advance of General Winfield Scott from the port of Veracruz. Despite the earnest efforts of the San Patricios and their expertise in artillery, both battles badly damaged Mexican defenses. The fate of the battalion was sealed at the Battle of Churubusco, on the outskirts of Mexico City, on August 20, 1847, where an estimated 75 of them were captured. By all accounts they fought fiercely to the end, with the knowledge that capture was almost certain to mean execution. Their skill and dedication were recognized by Santa Anna, who later asserted that with a few hundred more like them, he could have won the war.

In the weeks that followed, punishment would be meted out under the direction of Scott, who issued a series of orders outlining who would be hanged and who would have the comparative fortune of being lashed and branded. Riley, the unit’s founder and most visible leader, was spared the gallows on a technicality, given that his desertion had preceded the formal declaration of war. Nonetheless he was reviled, and newspapers gladly carried news of his punishment as conveyed in dispatches compiled from General Scott’s Army: “Riley, the chief of the San Patricio crowd, came in for a share of the whipping and branding, and right well was the former laid on by a Mexican muleteer, General (David) Twiggs deeming it too much honor to the Major to be flogged by an American soldier. He did not stand the operation with that stoicism we expected.”

Though celebrated in newspapers, the viciousness of these punishments shocked many observers, eliciting opposition not only in the Mexican public but among foreigners as well. “The San Patricios who died by hanging were treated that way because the U.S. Army wanted revenge,” says Greenberg

At the end of the war, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed February 2, 1848, dictated that any remaining San Patricios held prisoner would be released. Some of the surviving San Patricios, including Riley, remained affiliated with Mexico’s military. According to Hogan, while some stayed in Mexico for the rest of their lives, others sailed back to Europe. (Concrete evidence of Riley’s whereabouts peter out several years after the war’s end).

Today the men who died fighting in El Batallón de San Patricio are commemorated in Mexico every year on St. Patrick’s Day, with parades and bagpipe music. A plaque bearing their names with an inscription of gratitude, describing them as “martyrs” who gave their lives during an “unjust” invasion, stands in Mexico City, as does a bust of Riley. Fiction books and even a 1999 action movie, One Man’s Hero, glamorize their actions. The San Patricios have been both reviled and revered in the retelling of their story over for more than 170 years, a testament to how deeply they embodied the layers of contradiction in a polarizing war between Mexico and the United States.