Keeping Feathers Off Hats–and On Birds

A new exhibit examines the fashion that led to the passage, 100 years ago, of the Migratory Bird Act Treaty

:focal(576x153:577x154)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/67/77/6777128e-90fa-4191-b7c7-a42e24e6549d/27739v-wr.jpg)

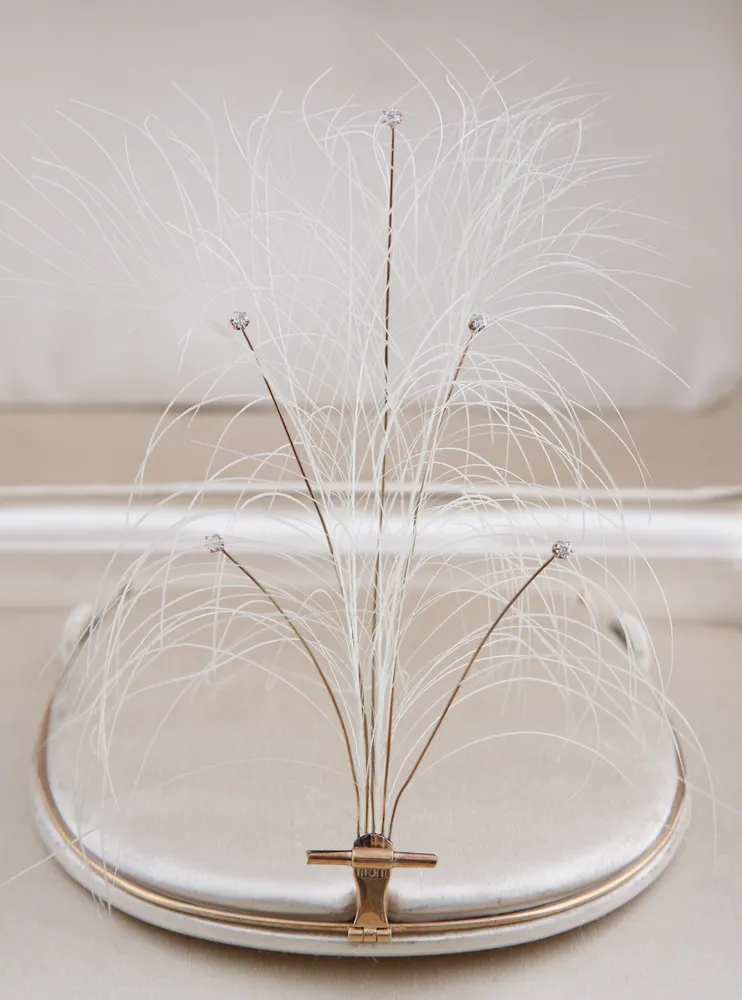

It’s easy to imagine the glamorous early 20th-century woman who might wear the tiara in front of me. Delicate and adorned with wispy white feathers that wouldn’t come cheap, this aigrette (the French word for egret) would rest atop the head of a rich and fashionable society figure. Such an ornament made of feathers represented the height of contemporary style.

And for many others, the tiara would be a walking symbol of man’s inability to respect the natural world, for as a 1917 Field and Stream story on migratory birds and the devastation fashion wrought upon them notes, each bunch of feathers on an aigrette “probably means that a mother egret has been murdered and her three or four baby herons have been left to starve to death in the nest.”

These birds, and their repurposing as gaudy fashion statements, are the subject of a new exhibit at the New-York Historical Society marking 100 years since the passage of the 1918 Migratory Bird Act Treaty, a piece of legislation that put a swift end to the hunting of birds like egrets (and swans, eagles and hummingbirds). Open through July 15, Feathers: Fashion and the Fight for Wildlife showcases a collection of garments and accessories made with the feathers, beaks, and in some cases, the full bodies of dead birds. Paintings by John James Audubon depict those same birds alive and in-flight, making a case for what activists, governments, and ordinary citizens can do in the face of seemingly inevitable environmental destruction.

It took the feathers of four egrets to produce one aigrette, a fact reflected in the sheer number of birds killed. Exhibit co-curator Debra Schmidt Bach says one set of statistics suggests that in 1902, one-and-a-half tons of egret feathers were sold, which according to contemporary estimates, calculates to 200,000 birds and three times that many eggs. By other figures, the number of birds being killed by hunters in Florida alone each year was as high as five million.

Milliners decorated hats with entire birds (often dyed in rich purples and blues), earrings made from the heads and beaks of hummingbirds, and a muff and tippet made from two Herring gulls, a species pushed almost to the brink of extinction in the 1900s. The set is especially poignant because, as co-curator Roberta Olson points out, their distinctive red markings indicate the gulls were harvested while they were breeding. “So it's kind of heartbreaking,” she says. “It's as though that's a mating pattern that will face each other for all eternity.”

The demand for birds and their feathers reached a fever pitch at the turn of the 20th century, and both curators hypothesize that as cities expanded, it was easier to feel increasingly distant from nature. Ironically, they saw the use of birds in fashion was a way to foster a connection with the animal world. And while Bach acknowledges that women were the “most visible purveyors and users of feathers,” hunters, scientists, and collectors contributed equally to the decimation of bird populations.

That didn’t stop the news media from blaming women for the mass die-off of migratory birds: the aigrette came to be known as the “white badge of cruelty,” and a 1917 Washington Post story challenges bird lovers to push back against “selfishly indifferent followers of fashion.”

Perhaps less talked about were the women—often Italian immigrants—who earned their wages directly through the production of these hats. The exhibit introduces us to a family doing a kind of work called willowing—a way of extending ostrich feathers – labor that might earn them $2.50 a week, or the equivalent of $75 in today's money, and a comparatively high wage for unskilled workers. The work put them at risk for exposure to illness that might come from doing dusty, repetitive work in small, unventilated tenement spaces. They suffered as well, through reduced wages, when the public demand shifted to bird-free alternatives like the “Audobonnet,” named after the environmentalist and made from silk and ribbon.

The popularity of Audobonnets and other cruelty-free accessories can be traced directly to the women who campaigned tirelessly to end the use of migratory birds in fashion. Some, like Florence Merriam Bailey, who as a Smith College student in 1886 organized a local chapter of the Audubon Society, combined their activism with work that pushed others to appreciate the beauty of birds in their natural habitats. Bailey’s Birds Through an Opera-Glass, published in 1899, helped non-experts spot, identify and appreciate bird life, and over the course of her ornithology career she’d write six birding books focused primarily on birds of the southwestern United States.

Others, like German opera star Lilli Lehmann, used their celebrity to bring attention to the cause. “One of the things that she would do,” Bach says, “is when she met her fans, or when she had different kinds of audiences that she could speak to, she would encourage women not to wear feathers, and in exchange, would offer her autographs—if they made the promise not to wear feathers.”

As the public took increasing interest in saving and restoring bird populations, individual states passed laws regulating the hunting and collection of birds, eggs and feathers, but migratory birds—those most impacted by the feather trade—remained without protection at the federal level until the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. According to the Audubon Society, the MBTA is “credited with saving numerous species from extinction, such as the Snowy Egret, Wood Duck, and Sandhill Crane, and millions, if not billions of other birds.”, and while hats decorated with the feathers of non-migratory birds like chickens and ostriches remained popular, aigrettes and other accessories featuring the plumes and parts of migratory birds vanished from the heads of fashionable women.

The egret now serves as the Audubon Society’s emblem, and Bach and Olson point to the naturalist’s famed watercolor portraits of migratory birds as an example of how to celebrate and admire wildlife from afar. Audobon, painting in the 1820s and 1830s, was one of the first artists to capture the images of birds in their natural habitats and part of their success, says Olson, is how Audubon presented his avian subjects.

“Notice how Audubon's birds always look at you,” she says says. “They’re alive, he uses the reserve of the paper to be the reflection in the eye. And so you feel like you're having a relationship with them.” While Audubon died in 1851, his art and work remain central to American conservation movements--Bach and Olson both call his work ahead of its time and instrumental in the development of later activists, many of whom organized Audubon Society chapters of their own.

The exhibit, and the chance it gives us to see the majesty of these birds, comes at a crucial time—the Department of the Interior recently announced plans to reinterpret the MBTA to weaken punishments for “incidental” destruction of birds and eggs. While the government suggests this interpretation is meant to benefit average citizens—a homeowner who might accidentally destroy an owl’s nest, for example—many in conservation circles think it will be used as a loophole for corporations to wreak havoc on bird populations with little to no punishment.

Before I leave, Olson shows me one more Audubon watercolor, this one of an egret. “You can see he is lifting off his back flip, as though it were a windup toy. And you can see, it's just so full of tension and life. And it's alive.”

It shows, she says, what the Migratory Bird Treaty Act really did. “And there is an undercurrent, I think, all for sustainability. And if one is a good steward of the environment, and of nature, we can get along.”