Thermopylae, the narrow pass above Greece’s Malian Gulf, is most famous for the legendary last stand of King Leonidas and his storied band of 300 Spartans in 480 B.C.E. But the site has seen dozens of crucial battles since then, owing largely to its strategic importance as a choke point for imperial powers hoping to gain access to critical Mediterranean ports or the rich cities of Greece. Perhaps the most daring and least known of these actions took place in 1943, when Brigadier Eddie Myers led a team of British Special Operations Executive officers who parachuted into Axis-held Greece, determined to disrupt the enemy by any means necessary. The rugged, mountainous terrain that Leonidas had used so well nearly 2,500 years earlier quickly drew the eyes of these audacious saboteurs.

Among their primary targets were two bridges that held up a vital railway across Greece. In late 1942, the officers launched Operation Harling, attacking the first bridge; with the help of Greek rebels, they succeeded in putting the railway out of commission for six weeks. The following year, as successes in North Africa led the Allies to seek ways to distract the Axis from a planned invasion of Southern Europe through Sicily, the men set their sights on the second bridge, called the Asopos Viaduct. It carried train tracks across a deep gorge that emptied into the valley through which the Persians had outflanked Leonidas long ago.

Myers knew that destroying the second bridge could hamper the Axis leaders’ response to the Allied advance. But the bridge was protected by a garrison of 50 German soldiers with machine gun nests and searchlights, making it unassailable from the valley below—or even from the railway tracks themselves.

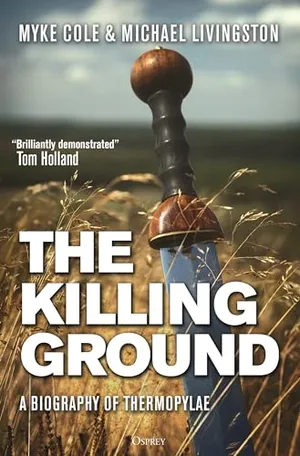

The Killing Ground: A Biography of Thermopylae

An exploration of why and how Thermopylae is one of the most blood-soaked patches of ground in history.

The local rebels said they would need thousands of men to take it out. Myers’ saboteurs numbered a mere six.

These were British Captains Geoffrey Gordon-Creed and Ken Scott, as well as Lieutenants Harry McIntyre and Don Stott, the latter a commando from New Zealand. With them were two escaped prisoners of war whom the group, as Myers later put it, “had picked up in Greece”: the Scottish Lance Corporal Charlie Mutch and Sergeant Michael Khuri, a Palestinian Arab who’d been involved in Operation Harling the previous year.

Though little remembered, the story of their successful mission, code-named Operation Washing, offers a masterclass in determination and daring worthy of Leonidas—alongside the dumb luck that often makes the difference in war.

With a direct assault out of the question, the Special Operations officers knew they’d need to use stealth to detonate the bridge’s supports. A stream wound through the gorge to the bridge, a path so dangerous that few thought it a viable option. As a fellow officer reported, it would be, “practically speaking, impossible. And because the Germans regard it as impossible, a determined party just might succeed.”

Three operatives conducted the initial reconnaissance, making a seven-hour hike across the mountains to the head of the gorge to determine how hard it would be to reach the viaduct through this unexpected avenue of approach, a veritable back door. The gorge leading down to the bridge in the valley wasn’t long—it extended just 1,300 yards west, upstream from the viaduct—but it was deep and treacherous, its icy waters as cold in the shadows as the upstream glacier that fed them. The men waded on in agony. “Torrent filled,” Myers would later write of the Asopos Gorge, noting that it was a painfully narrow track between vertical mountain faces. Even viewed by satellite today, it’s such a sharp gash that it looks for all the world like some god of old cleaved the mountains with an ax.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5f/16/5f16a92f-63c2-4acd-b1b6-77d274133c6b/soe.jpg)

The men were probably the first to ever descend the gorge. What they found was otherworldly, observed historian M.B. McGlynn in 1953:

The sun never entered the gorge, and the only passage for most of the way was through the freezing cold water or along the steep cliff sides. The heartbreaking barriers were the waterfalls, with side walls worn smooth as glass.

Blocked in their descent by a monstrous waterfall, the three exhausted men returned to their base and collected parachute rigging, which they wove into 340 feet of makeshift rope. With this gear in hand, they gathered stores of explosives and other supplies and, on May 21, headed out on mules as part of a larger group, back along the path they had reconnoitered to the western end of the gorge. The encampment they made that night was bitterly cold, Gordon-Creed later recalled, “and the place was alive with scorpions.” As miserable as the situation was, it was nothing compared to what he and his men encountered when they dropped back down into the watery depths of the chasm on May 22. As Gordon-Creed wrote:

The next four days were a nightmare I would prefer to forget. Each day we would crawl out of our blankets, brew up something hot and shiver our way into that damnably icy river, and each day, after hours of swimming, climbing and struggling, we would get a few yards further down the gorge. The force of the current was terrifying, and we knew that a slip would almost certainly mean death by drowning or by being battered over a 40-foot waterfall.

The experience was nothing that the men had trained for. Myers commended them for the mental toughness required to keep “struggling in the gorge, sometimes with water up to their necks, completely cut off from the outside world, sometimes only with the greatest difficulty overcoming symptoms of claustrophobia brought on by the enclosed nature of the gorge.” At every step, rocks could give way above them, or their legs could give out below them. Descending the shadowed pass would be grueling, perilous and unimaginably cold even with 21st-century gear. These men had only their “brown army gym shoes, navy blue shorts and T-shirts,” as Gordon-Creed noted.

It took the group two days to prepare a route suitable for advancing supplies, including the precious explosive charges, which they now carefully hauled in. In addition to the challenge of simply making their way without breaking a leg or developing hypothermia from the freezing water, the men had the added challenge of keeping the explosives dry. Their rope-rigging skills met this challenge, lowering the explosives down past waterfalls and constructing impromptu aerial rope bridges to haul the explosives down cliff faces at a steep enough angle to keep them clear of the water.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/93/e1/93e1dd64-2d0c-4efb-a754-2f99c6950d97/thermopylae.jpeg)

By May 25—less than two weeks after the North African campaign came to an end and the Allies began readying for the invasion of Sicily that this operation was meant to aid—the special operatives had descended an estimated two-thirds of the gorge’s length, roping down two major waterfalls and navigating countless obstacles between. But now they were struck with “a moment of near despair,” Gordon-Creed wrote, because “the torrent rushed down a high smooth corridor of rock, smashed around a huge boulder and vanished over a fall, the height of which we had no means of judging.” Worse, such were the conditions of the chasm that they “could find no projection around which we could belay a rope.” One of the men came up with the idea that a thick-enough tree, felled and then floated down the gorge to their position, might work as an anchor once they wedged it across the gap. This enterprise cost them another day, but it worked.

At this point, the team was only around 350 yards from the viaduct at the mouth of the gorge. But they were exhausted and had run out of their makeshift rope. They found a dry spot among the rocks to cache their explosives and supplies, then struggled up and out of the gorge and hiked back to their base. The return trip was just as brutal, but at least they no longer had to split their attention between the challenge of keeping moving and the additional task of hauling explosives that had to be kept dry.

Over the coming weeks, rope and other needed equipment were dropped to the men by parachute. On June 15, they finally had both the supplies and the energy needed to make what they hoped would be the final push. The Allied invasion of Sicily was now only three weeks away.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/74/d9/74d93a90-4e95-4cc0-97e5-144f3c869f75/gorgopotamos_viaduct.jpeg)

The first saboteurs in were Stott, Mutch and Khuri, as the mission would be best served by a small team testing if they could retrace their steps and then close the final distance to the bridge. Navigating their way downstream with the addition of ropes and hooks—even, at one point, felling a tall tree that they floated down the stream before hauling it out of the water and standing it up to be used as a ladder—they eventually made it to the end. Stott, forging ahead, rounded a bend and found himself face to face with the base of the viaduct. Coincidentally, the Germans were then repairing the northern support of the main span, with workers buzzing around a latticework of ladders and scaffolding. Two of the Germans were moving stones in the stream no more than ten yards from Stott, though he ducked out of sight before they could spot him. The hard work of the seemingly impossible descent had paid off. “The job’s in the bag,” Stott reported when he returned to the others.

Gordon-Creed, Scott and McIntyre soon joined the rest of the group in the gorge. On June 19, all six men began the tedious work of shifting the explosives, detonators and other supplies into final position and readying them for use. These exhausting labors took until the afternoon of the next day.

When night fell, the men crept up from the gorge, moving into position by the bridge’s main supports. More good news was ahead, as Gordon-Creed wrote in his after-action report:

By great good fortune, [it] was found that neat gaps had been cut through the barbed wire, … also that the enemy had been kind enough to leave a ladder leading up through the scaffolding to a platform about 100 feet up, from which point it was possible to reach the main girders. At this point, [Mutch and Khuri] were sent back up the gorge to prepare something hot and to strike camp ready for a hasty exit.

Next, Scott and McIntyre, who were responsible for the explosives, climbed up the scaffolding as quietly as they could, using a parachute cord to haul up the charges behind them. Both men were sappers, military engineers who specialized in the repair of fortifications, roads and bridges—or, in this case, destroying them. The remaining two members of the group kept watch. Before long, a German soldier appeared, walking down toward the stream. As the other men froze in place, Gordon-Creed, knowing the German would see the work and expose the whole operation, hid in a bush beside the track. The men had no weapons on them beside their hard rubber coshes—short bludgeons or batons. When the German passed by, Gordon-Creed used his: “There was nothing for it. Every ounce I had went into that wallop onto his head, and he went over and into the gorge without a sound.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ea/31/ea315749-1e5a-472a-a1ae-663b7117720f/asopos_viaduct_postcard.jpeg)

With the sappers making rapid progress, Stott retreated to find a place to observe the demolition. Despite their success up to this point, Myers later noted that “grave anxiety was felt as to whether the explosive was still serviceable as, owing to the depth of the water in places, it had had to be dragged through it.” They’d done their best to keep it all dry, even wrapping the fuses and detonators in condoms, but no one could be sure of the outcome.

After two hours of work, paused only when one of the German searchlights floated over their position or the moon shone too brightly between the clouds, Scott and McIntyre finished their task. They had set charges on four pillars holding up the bridge, connected with explosive fuse, then added five “time pencils” (pencil-sized time fuses connected to detonators) to set them off. Only one pencil was required, but they were taking no chances. At midnight, they crushed the pencils, giving them 90 minutes to reach a safe distance before acid ate the wires inside, detonating the entire construct. With their work completed, they met back up with Gordon-Creed.

As quietly as they’d come, the three men followed their comrades in withdrawing back up the gorge. They were roughly halfway out when, at 2:15 a.m.—the cold night having likely delayed the fuses—a bright flash lit up the sky behind them. They couldn’t see the destruction itself, but Myers would later record the result: “With one complete cut in the curved sections, the whole central arch collapsed into the gorge below, … where it lay, a jumbled mass of steelwork.” The sound of the explosion itself was so terrific that the saboteurs heard its “reverberating roar … over the noise of the torrent,” Gordon-Creed recalled. Standing in the waist-deep cold stream, the three exhausted men shook hands.

After the success of Operation Washing, it took the Nazis four months to reopen the important railway line. (The delay wasn’t for lack of trying: An initial replacement viaduct built in just five weeks collapsed, killing a German engineer and 40 workers.) By that point, the Allies had overrun Sicily and begun their invasion of the Italian mainland, opening up the underbelly of Axis-held Europe. The success of the saboteurs in Greece had made these hard labors easier: Even after the invasion of Sicily was underway, many in the Axis still thought Operation Washing was a precursor to an Allied invasion of the eastern end of the Mediterranean, and they wasted precious men and material guarding against it.

Two and a half millennia earlier, the outnumbered Leonidas used the unique terrain of Thermopylae to delay the advance of the Persian army. The outnumbered British now used it to thwart the Axis powers’ ability to delay the advance of the Allied armies. Once again, Thermopylae was a central pivot for important military action. Once again, it was a killing ground.

Adapted from The Killing Ground: A Biography of Thermopylae by Myke Cole and Michael Livingston. Published by Osprey Publishing. Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c6/ca/c6ca547e-f49f-470e-84a5-69dab59e303c/thermopylae.jpg)