Montpelier and the Legacy of James Madison

The recently restored Virginia estate of James Madison was home to a founding father and the ideals that shaped a nation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/montpelier_631.jpg)

The United States of America was born in April 1775, with the shots heard 'round the world from Lexington and Concord. Or it was born in July 1776, with the signing of the Declaration Independence in Philadelphia. Or it was born in the winter of 1787, when a 35-year-old Virginia legislator holed up at his estate and undertook a massive study of governmental systems around the world and over the ages.

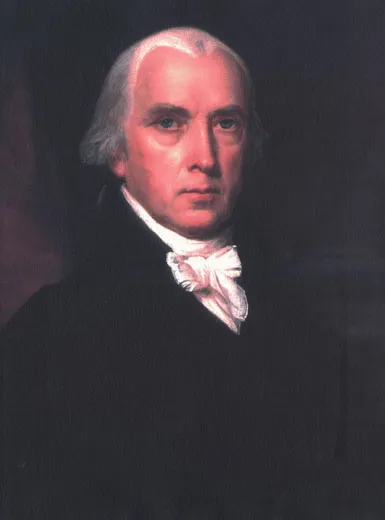

The legislator was James Madison, and it was through his winter's labor that he devised a system of checks and balances that would be enshrined in the Constitution of the United States that fall. Madison's estate, Montpelier, proved less durable than his ideas, but now, after a five-year, $24 million restoration, it has been reopened to visitors.

"Madison is back, and he's getting the recognition he deserves," says Richard Moe, president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which owns Montpelier. It may seem odd to think of Madison as being "back"—in addition to becoming known as the "father of the Constitution," he also served as Thomas Jefferson's secretary of state (1801-1809) and won two presidential terms of his own (1809-1817)—but then, he was overshadowed in his own time by his good friend Jefferson and the father of the country, George Washington.

"Without Washington, we wouldn't have won the revolution. Without Jefferson, the nation wouldn't have been inspired," says Michael Quinn, president of the Montpelier Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to presenting Madison's legacy. "What made our revolution complete was the genius of Madison.... He formed the ideals of the nation."

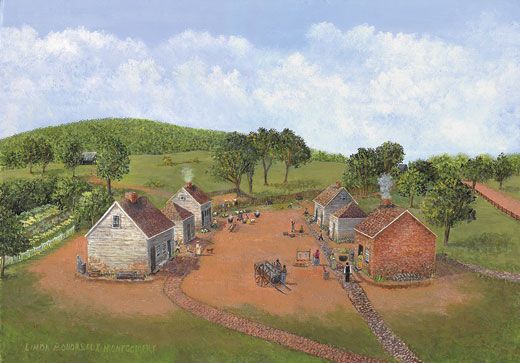

Montpelier, which lies a few miles south of Orange, Virginia, and about 90 miles southwest of Washington, D.C., is where Madison grew up and where he retired after his days as president were over. His grandparents had settled the estate in the early 1730s, and a few years after the future president was born, in 1751, his father began building the house where he would live.

Although Madison repeatedly left central Virginia—he graduated from the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), for example, and sat in the Virginia House of Delegates in Williamsburg and Richmond; he lived in Washington for almost the first two decades of the 19th century—he always returned to Montpelier.

In the late 1790s, he added several rooms to the relatively modest house his father had built, and during his first term as president he added wings to each side, creating a more stately home that matched his position. Once his days in Washington were done, Madison spent his years overseeing the plantation at Montpelier, growing wheat and tobacco and raising livestock.

He died there in 1836, at age 85, the last of the founding fathers to pass away.

After Madison died, his widow, Dolley, sold Montpelier to help repay the debts of her son from a previous marriage. (She returned to Washington, D.C., where she had been a very popular first lady.) The estate changed hands several times before William duPont, a scion of the duPont industrial dynasty, bought it in 1901 and expanded it from 22 rooms to 55 and covered it with pink stucco. When his daughter Marion duPont Scott died, in 1983, she left it to the National Trust for Historic Preservation with the proviso that it be restored to the way it was in Madison's time.

But for lack of funding, little work was done on the house for several years. The estate opened to the public in 1987, but "people took one look at the house and they knew it wasn't what it looked like in Madison's time," says Quinn of the Montpelier Foundation, which oversaw the restoration.

Once the restoration began, in late 2003, workers removed about two-thirds of William duPont's addition to uncover the original house. They found it so well-preserved that the majority of the floorboards from Madison's time remained. As the renovation proceeded, if workers couldn't use original materials, they painstakingly tried to replicate them, hand-molding bricks or combining plaster with horsehair.

Researchers used visitors' letters and other accounts to envision the house as it was during Madison's retirement years. Architectural plans from Madison's expansions were also an invaluable resource. Quinn says there was also a lot of forensic work: after stripping off coats of paint, for example, experts could see "shadows" revealing where certain pieces of furniture sat. Furnishing all of the mansion's current 26 rooms will take a few more years, Quinn says.

In the meantime, the Montpelier grounds are also home to the Center for the Constitution, a resource for advancing constitutional education—and another extension of Madison's legacy. When the mansion was reopened, in September, the chief justice of the United States, John G. Roberts, spoke from its front steps. "If you're looking for Madison's monument, look around," Roberts said. "Look around at a free country governed by the rule of law."