Monumental Mission

Assigned to find art looted by the Nazis, Western Allied forces faced an incredible challenge

The best birthday present Harry Ettlinger ever got arrived on the frigid morning of January 28, 1945. The 19-year-old Army private was shivering in the back of a truck bound from France toward southern Belgium. There the Battle of the Bulge, raging for most of a month, had just ended, but the fighting continued. The Germans had begun their retreat with the new year, as Private Ettlinger and thousands of other soldiers massed for a counterassault. "We were on the way east," Ettlinger recalls, "when this sergeant came running out. 'The following three guys get your gear and come with me!' he yelled. I was one of those guys. I got off the truck."

The Army needed interpreters for the forthcoming Nuremberg war trials, and someone had noticed that Ettlinger spoke German like a native—for good reason: he was a native. Born in the Rhine-side city of Karlsruhe, Ettlinger had escaped Germany with his parents and other relatives in 1938, just before the shock of Kristallnacht made it abundantly clear what Hitler had in mind for Jewish families like his. The Ettlingers settled in Newark, New Jersey, where Harry finished high school before being drafted into the Army. After several weeks of basic training, he found himself headed back to Germany—a place he had never expected to see again—where the last chapter of the European war was being written in smoke and blood.

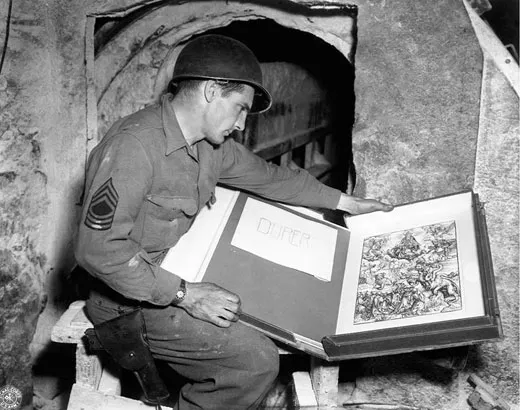

Ettlinger's Nuremberg assignment evaporated without explanation, and he was plunged into a thoroughly unexpected sort of war, waged deep in Germany's salt mines, castles, abandoned factories and empty museums, where he served with the "Monuments Men," a tiny band of 350 art historians, museum curators, professors and other unsung soldiers and sailors of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives section. Their task, begun with the uncertain peace of May 1945, was to find, secure and return the millions of pieces of art, sculpture, books, jewelry, furniture, tapestries and other cultural treasures looted, lost or displaced by seven years of upheaval.

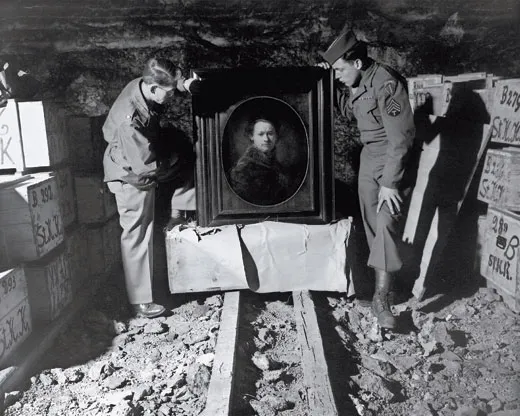

The conflict swallowed up a massive volume of cultural objects—paintings by Vermeer, van Gogh, Rembrandt, Raphael, Leonardo, Botticelli and lesser artists. Museums and homes throughout Europe had been stripped of paintings, furniture, ceramics, coins and other objects, as were many of the continent's churches, from which silver crosses, stained glass, bells and painted altarpieces disappeared; age-old Torahs vanished from synagogues; entire libraries were packed up and spirited away by the trainload.

"It was the largest theft of cultural items in history," says Charles A. Goldstein, a lawyer with the Commission for Art Recovery, an organization promoting restitution of stolen works. "I've seen figures every which way, but there is no question that the scale was astronomical."

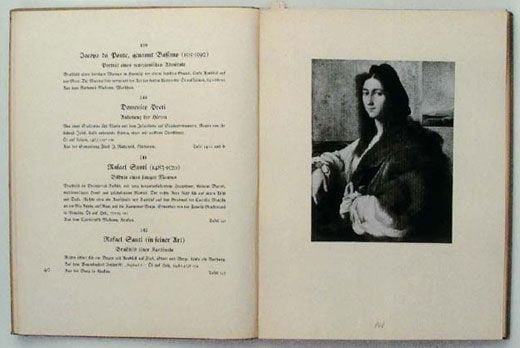

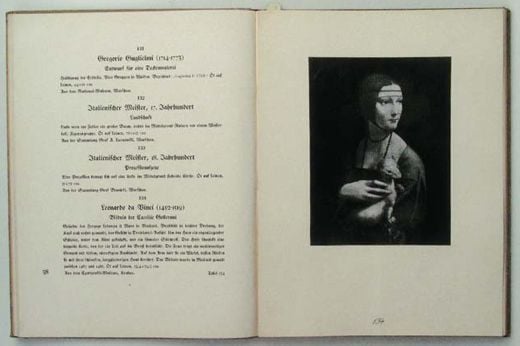

The most systematic looting, at the behest of Adolf Hitler and his reichsmarshal, Hermann Goering, swept up thousands of prime artworks in France, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Germany, Russia and other war-ravaged countries; indeed, in their thorough way of doing things, the Nazis organized a special squad of art advisers known as the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), which targeted Europe's masterpieces for plunder. Choice works were detailed in some 80 leatherbound volumes with photographs, which provided guidance for the Wehrmacht before it invaded a country. Working from this hit list, Hitler's army shipped millions of cultural treasures back to Germany, in the Führer's words, to "safeguard them there." From the other direction, Soviets organized a so-called Trophy Commission, which methodically picked off the cream of Germany's collections—both legal and looted—to avenge earlier depredations at the hands of the Wehrmacht.

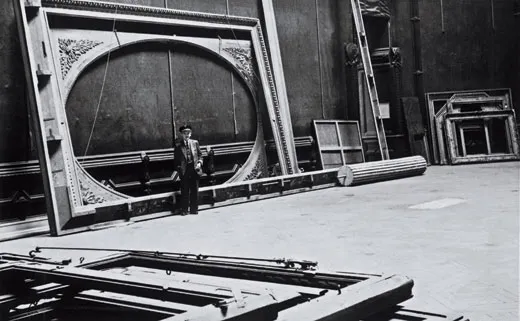

At the same time, state art repositories across Europe crated their prized collections and shipped them away in hopes of shielding them from Nazi looting, Allied bombing and Russian pillaging. The Mona Lisa, bundled into an ambulance and evacuated from the Louvre in September 1939, stayed on the go through much of the war; hidden in a succession of countryside châteaux, Leonardo's famous lady avoided capture by changing addresses no fewer than six times. The prized 3,300-year-old beauty Queen Nefertiti was whisked from Berlin to the safety of the Kaiseroda potash mine at Merkers in central Germany, where thousands of crates from the state museums were also stored. Jan van Eyck's Ghent altarpiece, a 15th-century masterwork the Nazis had looted from Belgium, was shipped to the mines of Alt Ausee, Austria, where it sat out the last months of the war alongside other cultural treasures.

When the smoke cleared, Hitler planned to unearth many of these spoils and display them in his hometown of Linz, Austria. There they would be showcased in the new Führer Museum, which was to be one of the finest in the world. This scheme died with Hitler in 1945, when it fell to Ettlinger and other Monuments Men to track down the missing artwork and provide refuge for them until they could be returned to their countries of origin.

"That's what made our war different," Ettlinger, now 82, recalls. "It established the policy that to the victor do not go the spoils. The whole idea of returning property to its rightful owners in wartime was unprecedented. That was our job. We didn't have much time to think about it. We just went to work."

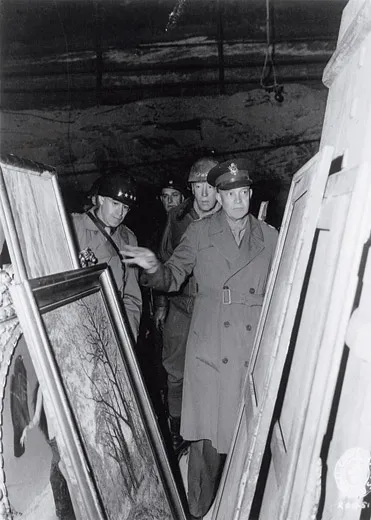

For Ettlinger, that meant descending 700 feet below ground each day to begin the long, tedious process of clearing artwork from the salt mines of Heilbronn and Kochendorf in southern Germany. Most of these pieces were not looted but belonged legally to German museums in Karlsruhe, Mannheim and Stuttgart. From September 1945 to July 1946, Ettlinger, Lt. Dale V. Ford and German workers sorted through the subterranean treasures, ferreting out works of questionable ownership and sending paintings, antique musical instruments, sculptures and other objects topside for delivery to Allied collecting points in the American zone of Germany. At major collecting points—in Wiesbaden, Munich and Offenbach—other Monuments teams arranged objects by country of origin, made emergency repairs and assessed claims by delegations who came to recover their nation's treasures.

Perhaps the most notable find at Heilbronn was a cache of stained-glass windows from the cathedral of Strasbourg, France. With Ettlinger supervising, the windows, packed in 73 cases, were shipped directly home without passing through a collecting point. "The Strasbourg windows were the first thing we sent back," says Ettlinger. "That was on orders of Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander of Allied forces, as a gesture of good faith." The windows were welcomed home with a huge celebration—a sign not only that the Alsatian city was free again after centuries of domination by Germany but also that the Allies intended to restore the fruits of civilization.

Most of Ettlinger's comrades had training in art history or museum work. "Not me," says Ettlinger. "I was just the kid from New Jersey." But he worked diligently, his mastery of German indispensable and his rapport with mineworkers easy. He was promoted to technical sergeant. After the war, he went home to New Jersey, where he earned degrees in engineering and business administration and produced guidance systems for nuclear weapons. "To tell you the truth, I wasn't as interested in the paintings as I was in other things over there," says Ettlinger, now retired in Rockaway, New Jersey.

Upon arrival at the Kochendorf mine, Ettlinger was shocked to learn that the Third Reich had intended to make it an underground factory using 20,000 workers from nearby concentration camps. The Allied invasion scuttled those plans, but a chill lingered over the mines, where Ettlinger was reminded daily of his great luck: had he not escaped Germany in 1938, he could have ended up in just such a camp. Instead, he found himself in the ironic position of supervising German laborers and working with a former Nazi who had helped pillage art from France. "He knew where the stuff was," Ettlinger says. "My own feelings couldn't enter into it."

Chronically understaffed, underfinanced and derided as effete "Venus fixers" by service colleagues, the Monuments Men soon learned to make do with very little and to maneuver like buccaneers. James Rorimer, curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's medieval collections in civilian life, served as a model for all Venus fixers who followed him—inventive and fearless in the face of authority. When someone on Gen. Eisenhower's staff filled the supreme commander's residence with old paintings and furniture from the Versailles Palace, Rorimer indignantly ordered them removed, convinced that he was engaged in nothing less than safeguarding the best of civilization.

Capt. Rorimer arrived in Heilbronn just as the ten-day battle for that city shut off the electrical supply, which caused the mine's pumps to fail, threatening massive flooding of the treasures below. He made an emergency appeal to Gen. Eisenhower, who, having forgiven the officer's earlier furniture removal operation, dispatched Army engineers to the scene, got the pumps going and saved thousands of pieces of art from drowning.

Rorimer also went head-to-head with the fearsome Gen. George S. Patton. Both men wanted to take over the former Nazi Party headquarters in Munich—Patton for his regional Third Army command center, Rorimer for processing artwork. Rorimer somehow convinced Patton that he needed the building more, and Patton found offices elsewhere. Few people who had seen Rorimer in action were surprised when, after the war, he was chosen as director of the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. He died in 1966.

"It helped to be a little sneaky," says Kenneth C. Lindsay, 88, a Milwaukee native who thoroughly detested Army life until he read of Rorimer's exploits, applied for a transfer from the Signal Corps, became a Monuments Man and reported to the Wiesbaden Collecting Point in July of 1945.

There Sgt. Lindsay found his new boss, Capt. Walter I. Farmer, an interior decorator from Cincinnati, bustling around the former Landesmuseum building, a 300-room structure that had served as a state museum before the war and as a Luftwaffe headquarters during the conflict. It had miraculously survived repeated bombings, which had nonetheless shattered or cracked its every window. The heating system had died, a U.S. Army depot had sprouted in the museum's former art galleries, and displaced German citizens had taken over remaining nooks and crannies of the old building. Farmer, Lindsay and a complement of 150 German workers had just under two months to depose the squatters, fire up the furnace, root out the bombs, fence off the perimeter and prepare the museum for a shipment of art scheduled to arrive from wartime repositories.

"It was a nightmare," recalls Lindsay, now living in Binghamton, New York, where he was chairman of the art history department of the State University of New York. "We had to get the old building going. Well, fine, but where do you find 2,000 pieces of glass in a bombed-over city?"

Farmer took matters into his own hands, deploying a crew to steal the glass from a nearby Air Force site. "They came back with 25 tons of glass, just like that!" says Lindsay. "Farmer had larceny in his veins, God bless him! My job was to get the workers to install the glass so that we had some protection for the art we were about to receive."

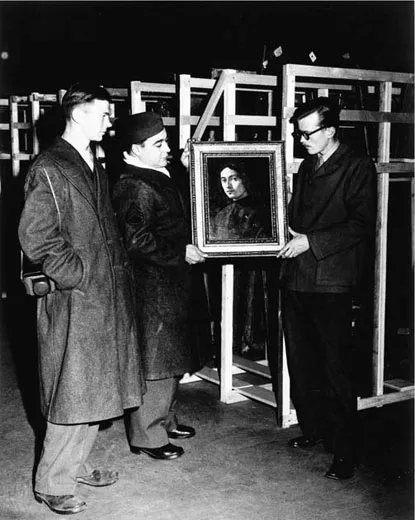

Lindsay was there to greet the first convoy on the morning of August 20, 1945, when 57 heavily loaded trucks, escorted by armed tanks, rumbled up to the Wiesbaden Collecting Point. Capt. Jim Rorimer rode like a proud potentate at the head of the motorcade, a bumper-to-bumper procession of artwork stretching miles from Frankfurt. As the first trucks backed up to the Wiesbaden storage areas and began to unload their cargo without incident, Rorimer turned to Lindsay. "Good work you're doing," he barked before racing off to his next crisis. "And that," says Lindsay, "is the only compliment I ever got in my whole time in the Army."

After the brutalities of a long war, those gathered at Wiesbaden were particularly touched when one old friend showed up that morning. Germans and Americans alike heaved a collective sigh of relief as the crate containing Queen Nefertiti rolled onto the docks. "The Painted Queen is here," a worker cried. "She's safe!" Having escaped Berlin, survived burial in the mines, rattled up the bombed-out roads to Frankfurt and endured seclusion in the vaults of the Reichsbank, the beloved statue had finally arrived.

She would have plenty of company in Wiesbaden, where the cavalcade of trucks kept coming for ten days straight, disgorging new treasures in a steady stream. By mid-September, the building was brimming with antiquities from 16 Berlin state museums, paintings from the Berlin Nationalgalerie, silver from Polish churches, cases of Islamic ceramics, a stash of antique arms and uniforms, thousands of books and a mountain of ancient Torahs.

When a delegation of high-ranking Egyptians and Germans came to check on Nefertiti, Lindsay arranged an unveiling—the first time anyone had gazed upon the Egyptian queen for many a year. Workers pried open her crate. Lindsay peeled off a protective inner wrapping of tarpaper. He came to a thick cushioning layer of white spun glass. "I leaned down to pull the last of the packing material away and I'm suddenly looking into Nefertiti's face," says Lindsay. "That face! She's gazing back at me, 3,000 years old but just as beautiful as when she lived in the 18th Dynasty. I lifted her out and put her on a pedestal in the middle of the room. And that is when every man in that place fell in love with her. I know I did."

The majestic Nefertiti, carved from limestone and painted in realistic tones, reigned at Wiesbaden until 1955, when she was returned to Berlin's Egyptian Museum. She resides there today in a place of honor, charming new generations of admirers—among them her fellow Egyptians, who maintain that she was smuggled out of their country in 1912 and ought to be returned. Although Egypt recently renewed its claim for Nefertiti, Germany has been unwilling to give her up, even temporarily, for fear that she might be damaged in transit. Besides, the Germans say, any works legally imported before 1972 can be kept under the terms of a Unesco convention. Yes, say the Egyptians, but Nefertiti was exported illegally, so the convention does not apply.

At least Nefertiti has a home. The same could not be said for the cultural treasures that finished the war as orphans, with no identifiable parentage and no place to go. Among these were hundreds of Torah scrolls and other religious objects looted from European synagogues and salvaged for a prospective Nazi museum devoted to "the Jewish question." Many of these objects, owned by individuals or communities obliterated by the Third Reich, were given their own room at Wiesbaden.

Stalking the corridors of the vast Landesmuseum at all hours, Lindsay felt an involuntary shudder each time he passed the Torah room. "It was an unnerving situation," he said. "We knew the circumstances that had brought those things in. You couldn't sleep at night."

Wiesbaden's inventory of famous paintings and sculptures was whittled down and repatriated—a process that took until 1958 to complete—but the Torahs and other religious objects remained unclaimed. It soon became clear that a new collecting point was needed for these priceless objects still being unearthed in postwar Germany.

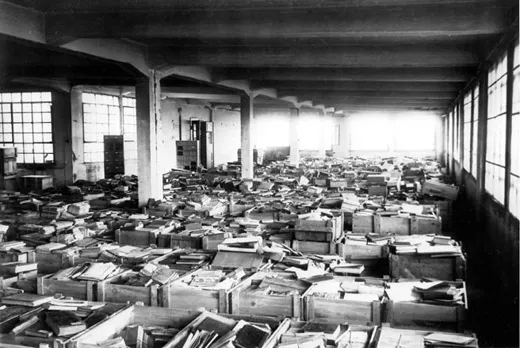

This material was sent to the newly established Offenbach Archival Depot near Frankfurt, where more than three million printed items and important religious materials would be gathered from Wiesbaden, Munich and other collecting points. The Offenbach facility, located in a five-story factory owned by the I.G. Farben company, opened in July 1945. Several months later, when Capt. Seymour J. Pomrenze, a career Army officer and archives specialist, arrived to supervise the facility, he found the depot stacked to the ceilings with books, archival records and religious objects in disarray.

"It was the biggest mess I've ever seen," recalls Pomrenze, 91, and now living in Riverdale, New York. Libraries stolen from France—including the invaluable collections and papers of the Rothschild family—were mingled with those from Russia and Italy, family correspondence was scattered among Masonic records and Torah scrolls were strewn in heaps.

"The Nazis did a great job of preserving the things they wanted to destroy—they didn't throw anything out," says Pomrenze. In fact, he jokes, they might have won the war if they had spent less time looting and more time fighting.

He found a bewildered staff of six German workers wandering among the piles of archival material at Offenbach. "Nobody knew what to do. First we needed to get bodies in there to move this stuff," recalls Pomrenze, who boosted the staff by 167 workers in his first month. Then, leafing through the major collections, he copied all identifying bookmarks and library stamps, which pointed to a country of origin. From these he produced a thick reference guide that allowed workers to identify the collections by origin.

Pomrenze then divided the building into rooms organized by country, which cleared the way for national representatives to identify their material. The chief archivist of the Netherlands collected 329,000 items, including books stolen from the University of Amsterdam and a huge cache relating to the Order of Masons, considered anti-Nazi by the Germans. French archivists claimed 328,000 items for restitution; the Soviets went home with 232,000 items; Italy took 225,000; smaller restitutions were made to Belgium, Hungary, Poland and elsewhere.

No sooner had Pomrenze started to make a dent in the Offenbach inventory than newly discovered materials poured into the depot; the paper tide continued through 1947 and 1948. "We had things pretty well organized by then," says Pomrenze. Yet even after some two million books and other items had been dispersed, about a million objects remained. Pomrenze's successor described how it felt to comb through the unclaimed material, such as personal letters and boxes of books. "There was something sad and mournful about these volumes, as if they were whispering a tale of...hope, since obliterated," wrote Capt. Isaac Bencowitz. "I would find myself straightening out these books and arranging them in the boxes with a personal sense of tenderness, as if they had belonged to someone dear to me."

Pomrenze eventually helped to find homes for many of the orphaned materials, which went to 48 libraries in the United States and Europe and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City.

"As far as I am concerned," says Pomrenze, "that was the highlight of the assignments I had in the Army, where I served for a total of 34 years." Pomrenze, who retired as a colonel and chief archivist of the Army, suggests that one must not lose sight of the written word's role in the story of civilization. "Paintings are beautiful and, of course, culturally valuable, but without archives we'd have no history, no way to know exactly what happened."

The lessons of the past are especially important to Pomrenze, a native of Kiev who immigrated to the United States at age 2, after his father was killed in the Ukrainian pograms of 1919. "The Ukrainians killed 70,000 Jews that year," says Pomrenze, who took quiet pride in helping to right the balance by his wartime service.

The Nazis recorded their thefts in detailed ledgers that eventually fell into the hands of officers like Lt. Bernard Taper, who joined the Monuments squad in 1946. "The Nazis made our job easier," says Taper. "They said where they got the stuff. They would describe the painting and give its measurements, and they would often say where they had sent the collection. So we had some very good clues."

Indeed, the clues were so good that Taper's colleagues had secured most of the high-value paintings—prime Vermeers, da Vincis, Rembrandts—by the time Taper arrived on the scene. That left him to investigate widespread looting by German citizens who pilfered from the Nazi hoard in the time between Germany's collapse and the Allies' arrival.

"There were probably thousands of pieces in this second wave, the looting of the looted," says Taper. "Not the most famous objects but many valuable ones. We looked for stuff on the black market, made regular checks among the art dealers and went out into the countryside to follow up promising leads."

Taper scoured the hills around Berchtesgaden, near the Austrian border, to recover the remains of Goering's vast art collection, thought to contain more than 1,500 looted paintings and sculptures. As Soviet troops pressed toward eastern Germany in the last days of war, Goering had feverishly loaded art from his Carinhall hunting lodge into several trains and dispatched them to air raid shelters near Berchtesgaden for safekeeping. "Goering managed to unload two of the cars, but not the third one, which was left on a siding when his entourage fled into the arms of the Seventh Army," he says.

The rumor quickly spread that the reichsmarshal's unguarded car was loaded with schnapps and other good things, and it was not long before thirsty Bavarians were swarming over it. "The lucky first ones did get schnapps," says Taper. "Those who came later had to be satisfied with 15th-century paintings and Gothic church sculptures and French tapestries and whatever else they could lay their hands on—including glasses and silver flatware with the famous H.G. monogram."

The loot disappeared into the green hills. "That country was so beautiful—it looked like something out of Heidi," Taper, 90, recalls while flipping through his official investigative reports from those days. He often traveled with Lt. Edgar Breitenbach, a Monuments Man who made the rounds disguised as a peasant, in lederhosen and a tiny pipe that kept him wreathed in a corona of smoke. They recovered much of the loot—a school of Rogier van der Weyden painting, a 13th-century Limoges reliquary and Gothic statues they tracked to the home of a woodcutter named Roth. "Herr Roth said he wasn't a thief," Taper recalls. "He said these statues were lying on the ground in the rain with people stepping on them. He said he took pity on them and took them home." Taper reclaimed them.

Not all of the cargo from Goering's schnapps train remained intact. During the melee by the rail siding, local women tussled over a 15th-century Aubusson tapestry until a local official suggested a Solomon-like solution: "Cut it up and divide it," he urged. And so they did, taking the tapestry away in four pieces. Taper and Breitenbach found its remains in 1947, by which time the hanging had been divided again. "One of the pieces was being used for curtains, one for a kid's bed," says Taper. The rest had vanished.

This was also the fate of one of the most important objects of Nazi looting, Raphael's Portrait of a Young Man, an early-16th-century painting that disappeared in the final days of the war. Over many months, Taper searched for the painting, which had been the pride of the Czartoryski Museum in Krakow until 1939, when one of Hitler's art agents snapped it up for the Führer, along with Leonardo's Lady With an Ermine and Rembrandt's Landscape With the Good Samaritan.

As far as Taper could determine, all three paintings had been rushed out of Poland in the winter of 1945 with Hans Frank, the country's Nazi governor general, as the Soviets bore down from the east. Arrested by Allies near Munich in May of that year, Frank surrendered the Leonardo and the Rembrandt, but the Raphael was gone. "It may have been destroyed in the fighting," says Taper. "Or it may have gone home with the Soviets. Or it may have been left on the road from Krakow to Munich. We just don't know." Unlike the other paintings, it was on panel, not canvas, so it would have been harder to transport and conceal. More than 60 years later, the Raphael remains missing.

Taper became a staff writer for The New Yorker and a professor of journalism at the University of California at Berkeley after the war. He still dreams about the Raphael. "It's always in color, even though all I ever had was a little black-and-white photograph." He pauses a long time. "I still think I should have found that damn thing."

Taper is one of a diminishing fraternity. Of the original 350 Monuments Men (including a score of Monuments Women) no more than 12 are known to be alive—just one reason a retired Texas oilman and philanthropist named Robert M. Edsel has made it his mission to call attention to their wartime deeds. "Theirs was a feat that must be characterized as miraculous," says Edsel, who has written about Taper, Ettlinger and their colleagues in a recent book, Rescuing Da Vinci; co-produced a documentary, The Rape of Europa; and persuaded Congress to pass resolutions recognizing their service. He has also established the Monuments Men Foundation for the Preservation of Art to safeguard artistic treasures during armed conflict.

"This group is an inspiration for our times," he adds. "We know they returned around five million cultural items between 1945 and 1951. I would speculate that 90 to 95 percent of the high-value cultural objects were found and returned. They deserve the recognition they never got."

Meanwhile, their story continues. Hundreds of thousands of cultural items remain missing from the war. Russia has confirmed that it holds many of the treasures, including the so-called Trojan gold of King Priam. Long-missing works are reappearing in Europe as one generation dies and old paintings and drawings emerge from attics. And hardly a month seems to pass without reports of new restitution claims from the descendants of those most brutalized by World War II, who lost not only their lives but also their inheritance.

"Things will keep appearing," says Charles A. Goldstein, of the Commission for Art Recovery. "Everything will surface eventually."

Robert M. Poole a contributing editor at Smithsonian, is researching a new history of Arlington National Cemetery.