Moonwalk Launch Party

The launch 40 years ago of Apollo 11, which put a man on the moon, brought Americans together during a time of nationwide unrest

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/people-watching-launch-of-Apollo-11-631.jpg)

In the summer of 1969, all eyes turned to a spit of land on Florida's Atlantic coast—the site of the Kennedy Space Center, named for the president who had challenged the nation to put a man on the moon before the end of the decade. That July, the Apollo 11 mission would attempt just that. I was 22, a year out of Colorado College and working as a photographer at Time magazine's Miami bureau. In the days before the launch, thousands of people drove from all over the country to see it firsthand, converging on Titusville, across the Indian River from NASA Launch Complex 39-A. I asked my superiors if I could cover these witnesses to history. The previous year had been one of division over the Vietnam War and trauma over the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, but now a sense of common purpose pervaded the beach. At 9:32 a.m. on July 16, the rocket's engines ignited amid a plume of smoke and flame. I didn't see it. I was looking into the faces of my proud, expectant countrymen.

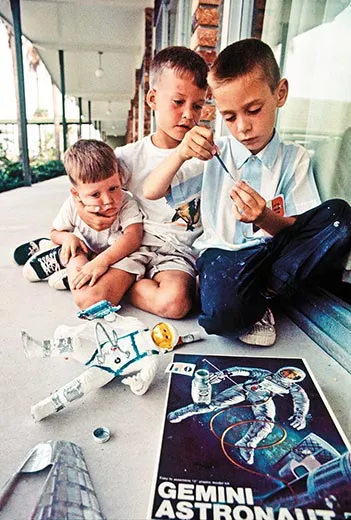

People brought their children, their folding chairs and their binoculars. The previous Christmas Eve, the Apollo 8 astronauts had read from the Book of Genesis as they orbited the moon; that hopeful mood translated into the selling of Apollo 11 souvenirs even before the flight. At takeoff, as the noise and the shock waves rippled across the water toward us, I told myself, "I'm not going to come all this way and not see the rocket." So I turned around and made one frame of it clearing the gantry before turning back to my assigned subject, the crowd.

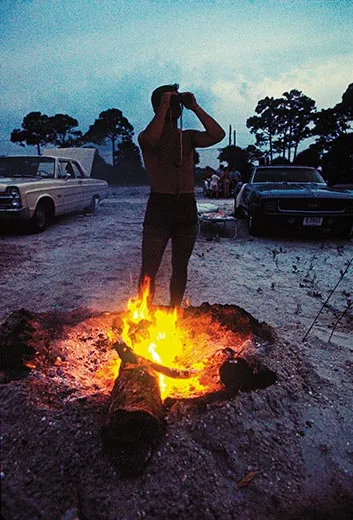

The day before the launch was like an exodus in reverse. Local officials expected nearly a million visitors, and it seemed as if their expectations would be met. Early arrivals staked out campsites on the Indian River across from the launch site or took rooms in motels, where space-related pastimes prevailed. As I sought spots from which I could shoot crowds on the beach, it dawned on me that I'd have to wade into the water; I made a mental note to look out for broken glass. that evening I headed over to a square dance at the local mall and was surprised to see a lot of people there. I couldn't say why, but a square dance seemed like a fitting send-off for the astronauts.

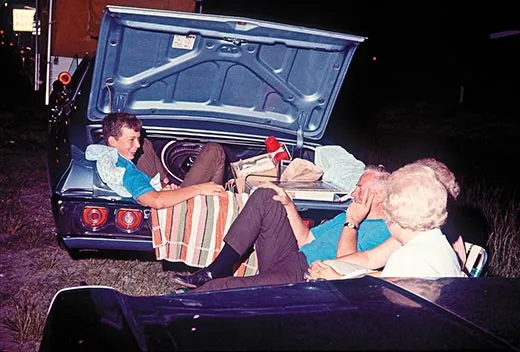

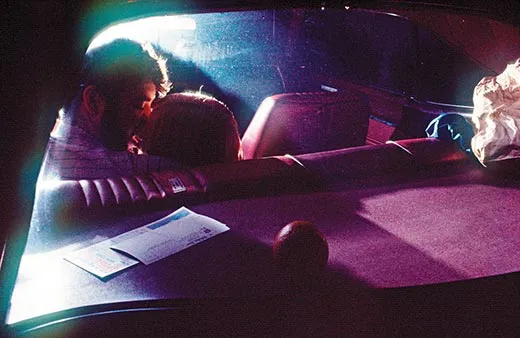

Around dusk the lights went up on the launchpad, and the vigil seemed to begin in earnest. Late into the night I photographed people sleeping in, on or beneath their cars, though I thought many of them were too excited to sleep. Women stood in a long file outside a gas station restroom without detectable annoyance, almost as if the wait were a badge of honor. Even after launch day dawned, hours passed before liftoff. It was so long in coming and so quickly gone, yet it remains burned into my memory like a slow-motion movie.

David Burnett returned to Florida this past May to shoot the launch of the mission to repair the Hubble space telescope.