For More Than 150 Years, Texas Has Had the Power to Secede…From Itself

A quirk of a 19th-century Congressional resolution could allow Texas to split up into five states

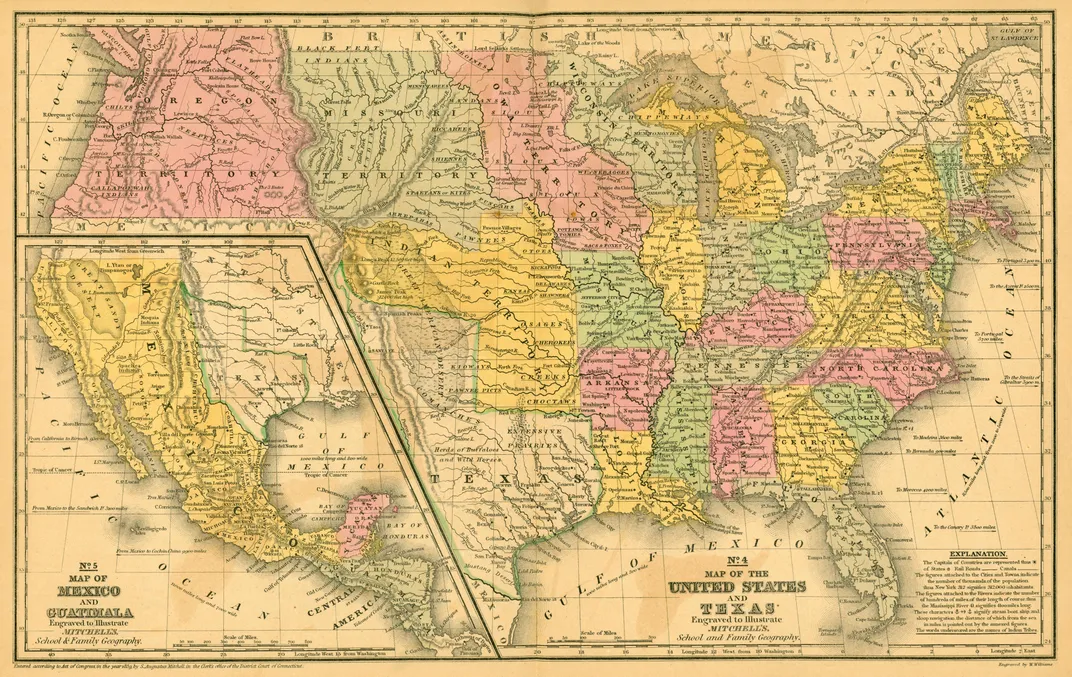

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b1/53/b15345ab-49dc-4c9c-a5f0-bdbfecb3d81f/de_cordova-tx-1851-03.jpg)

Before John Nance Garner became Franklin Roosevelt’s vice president, and before he declared the job “isn’t worth a pitcher of warm spit,” the cow-punching, whiskey-drinking, poker-dealing Texas congressman pushed a plan to grab even more clout for his already enormous state. Across his career, as a turn-of-the century Texas state legislator and in interviews given during his time in Congress and on the occasion of his 1932 ascension to Speaker of the House, “Cactus Jack” argued that Texas could, and should, split itself into five states.

“An area twice as large and rapidly becoming as populous as New England should have at least ten Senators,” Garner told The New York Times in April 1921, “and the only way we can get them is to make five States, not five small States, mind you, but five great States.” Thanks to the terms of Texas’ 1845 admission to the Union, he argued, the state could split anytime, without any action from Congress—a power no other state has.

Garner’s idea went nowhere. But the congressman from Uvalde, in the Hill Country west of San Antonio, was carrying on a long West Texas tradition of trying to turn the Lone Star State into a constellation. Dividing Texas into many little Texases was seriously considered at the time Texas became a state and for decades afterward. The idea survives today as a quirk in American law, a remnant of Texas’ brief history as an independent nation. It’s also a peculiar part of Texas’ identity as a state so big, it could split itself up—even though it loves its own bigness too much to do it.

“We’re the only state that can divide ourselves without anybody’s permission,” says Donald W. Whisenhunt, a Texas native and author of the 1987 book The Five States of Texas: An Immodest Proposal. “That’s just the way it is.”

Article IV, Section 3, of the U.S. Constitution states that Congress must approve any new states. But Texas’ claim to an exception comes straight from the 1845 joint congressional resolution admitting Texas into the Union. It reads: “New States of convenient size not exceeding four in number, in addition to said State of Texas and having sufficient population, may, hereafter by the consent of said State, be formed out of the territory thereof, which shall be entitled to admission under the provisions of the Federal Constitution.” Supporters of Texas division say this means that Congress pre-approved a breakup.

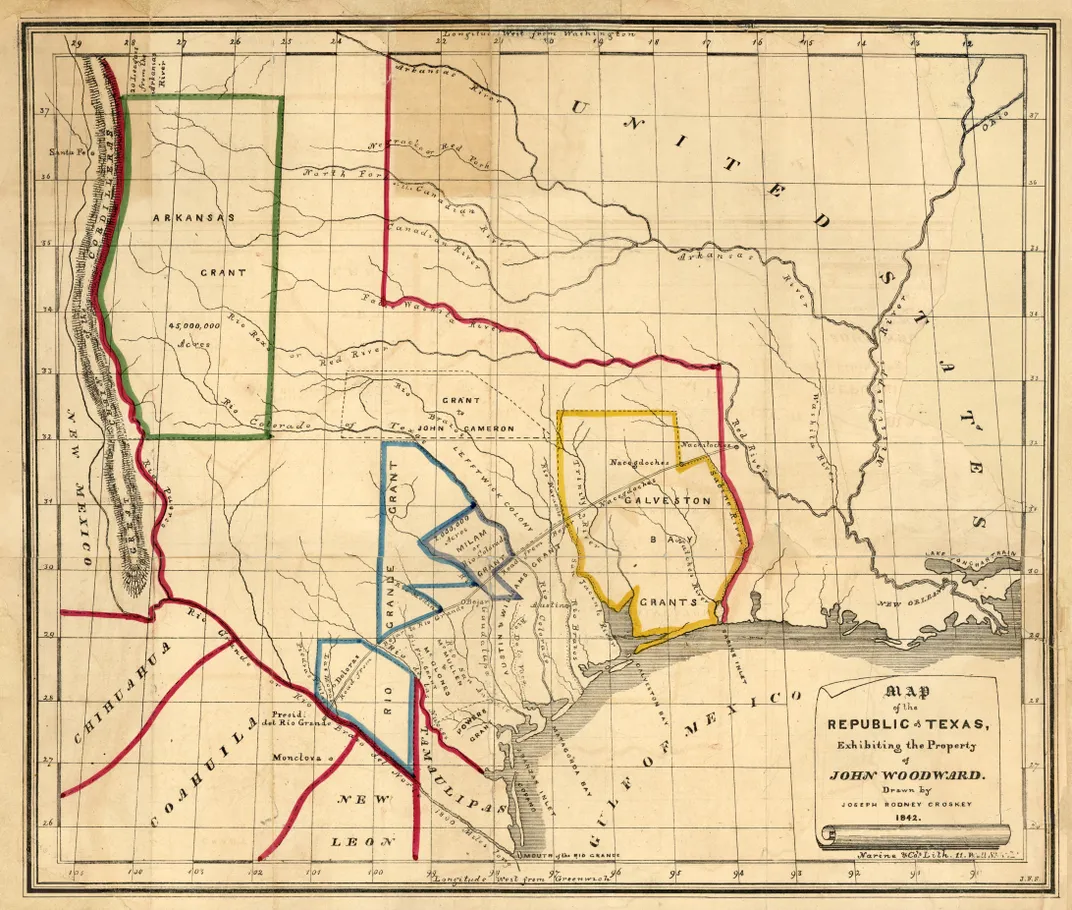

Slavery, and the tense power balance between North and South in the 1840s, explains the clause. When Texas joined the United States after nine years as an independent republic, it claimed even more territory than the 268,580 square miles it covers today. It laid claim to half of present-day New Mexico and a weird stovepipe of land, formed in part by the Rio Grande and Arkansas rivers, that reached north to what’s now central Colorado and bits of Oklahoma, Kansas and even Wyoming. That northern tip poked above the 1820 Missouri Compromise line, which did not allow slavery north of latitude 36 degrees, 30 minutes.

How would such a giant piece of the West be divided? In early 1845, when Congress debated Texas’ admission, Northern congressmen wanted to divide Texas in half, splitting the state in half diagonally, from the coast east of Corpus Christi up to the state’s northwest corner, with Austin just to the east and San Antonio to the west. Slavery would be prohibited in thinly populated West Texas, where many anti-slavery Germans had already settled.

But Southerners rejected that proposal as too restrictive of slavery. Instead, Isaac Van Zandt, the Texas republic’s top diplomat in Washington, pushed the four-new-states clause as a Southern-friendly alternative. “Van Zandt…became very intimate with the Senators and Representatives from the southern states,” wrote Weston Joseph McConnell in the 1925 book Social Cleavages in Texas. Van Zandt, like the Southerners, thought splitting Texas into a group of states would give the South more power. Texas’ admission to the Union, with the new-states clause included, passed Congress 120-98. The only concession to the North: Slavery would be prohibited in any states formed north of the Missouri Compromise line.

In 1847, Van Zandt ran for governor of Texas, promising to divide it into as many as four states. Dividing the state would give Texas more power in Washington, Van Zandt argued. He also thought that Texas, with its small settlements hundreds of miles apart, couldn’t be governed efficiently. (Making himself governor of a smaller state didn’t seem to bother Van Zandt, evidently.) Texas historians tend to think Van Zandt would likely have won and split up the state, if he hadn’t died of yellow fever a month before the election.

When Congress redrew Texas’ northern and western borders as part of the Compromise of 1850, paying Texas $10 million for what became eastern New Mexico and pieces of four other states, the statute included a line that preserved the new-states clause. But a proposal to split Texas into two states at the Brazos River failed in the state legislature, 33-15, in 1852. Most of its supporters came from east of the Brazos, another example of the widespread grievances between east and west Texas. Each accused the other of incompetence and neglect. But that quarrel lost out to Texans’ pride in their shared history. “Which State would yield the emblem of a single star?” asked the Texas State Gazette. “Who will give up the blood-stained walls of the Alamo?”

Texas again came close to breaking up during Reconstruction. Radical Republicans, elected at a time when most former Confederates couldn’t vote, tried to carve up Texas at its constitutional convention of 1868-1869. Their stated aim was to create a Union-friendly West Texas that might rejoin the U.S. earlier than the rest of the state; critics argued they were really trying to create more state offices for themselves. Pro-division delegates were a majority at the convention, but they couldn’t agree on a map—a recurring hurdle for Texas divisionism in the early years. “It’s impossible to get Texans, cantankerous as they are, to agree on a plan,” Whisenhunt says.

Stymied Radical Republicans wrote a “Constitution of the State of West Texas,” which promised civil rights for blacks while proposing to deny the vote to ex-rebels, Ku Klux Klan members, and newspaper editors and ministers who’d supported the Confederacy. (That provocative and potentially unconstitutional idea reflected Reconstruction debates about restoring ex-Confederates’ rights and citizenship.) But public opinion stood in opposition to their plan. Pro-division meetings attracted few people. Nearly every newspaper in the state rejected the idea. Some mocked the idea of creating a state in sparsely populated West Texas by suggesting alternate names: “The State of Prickley-Pear (Cactaea),” or “The State of Coyote.”

Thwarted, the radicals appealed to Ulysses S. Grant, president-elect and commanding general of the Army, to intercede. He didn’t. “One Texas was amply sufficient to have on hand for the present,” Grant told a reporter.

Texas never came close to dividing after that, though West Texas’ coyotes howled about leaving when they felt neglected. They threatened to break up the state in April 1921 after Governor Pat M. Neff vetoed a bill to build a college in West Texas. The same day as the veto, 5,000 angry West Texans met in the town of Sweetwater and drafted resolutions calling for a breakup unless the legislature redistricted the state and built the college. Their threat may have inspired Garner’s division talk with The New York Times later that month.

“For the next three years west Texans assumed a militant attitude both in and out of the legislature,” wrote Ernest Wallace in his 1979 book The Howling of the Coyotes. The legislature established Texas Technological College, now Texas Tech University, in Lubbock in 1923. “This token appeasement quieted the division sentiment,” Wallace wrote.

In 1930, Garner brought up division again, out of anger at Congress for passing the Smoot-Hawley tariff. “Texas would make 220 States the size of Rhode Island, 54 the size of Connecticut, six the size of New York,” argued Garner, still hoping a divided Texas could outvote the Yankees.

Garner was the last prominent politician to support Texas division, but the idea still lives on as a what-if in political junkies’ obsessive blue-red map-gaming. In 2009, Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight drew up a fantasy five-way split that created three Republican mini-Texases, a blue state along the Rio Grande, and a swing state around Austin. “Let’s Mess With Texas,” a 2004 Texas Law Review paper, argued that wily Texas Republicans could use the 1845 new-states clause to gerrymander their way to eight more U.S. Senate seats and Electoral College votes. A response from Ralph H. Brock, a former State Bar of Texas director, argued that the new-states clause would violate the Supreme Court’s equal-footing doctrine.

The idea that Texas could divide and grab eight more Senate seats appeals to Texans’ self-image as a unique, sprawling, powerful state. But that same sense of self will prevent Texans from ever actually trying it.

“It’s a novel idea that they might like at first glance,” Whisenhunt says. But 30 years after he wrote his book encouraging Texas division, he’s now convinced it’s basically impossible. How to divide Texas’ oil wealth, which funds its major state universities? Besides, Whisenhunt, 78, recalls the wound to the Texas psyche when Alaska displaced it as the largest state in 1959. “There’s a strong amount of pride in being the biggest, the best, and the first,” he says.