The Most Treacherous Battle of World War I Took Place in the Italian Mountains

Even amid the carnage of the war, the battle in the Dolomites was like nothing the world had ever seen—or has seen since

Just after dawn we slipped into the forest and hiked a steep trail to a limestone wall. A curious ladder of U-shaped steel rungs was fixed to the rock. To reach the battlefield we would trek several miles along this via ferrata, or iron road, pathways of cables and ladders that traverse some of the most stunning and otherwise inaccessible territory in the mountains of northern Italy. We scaled the 50 feet of steel rungs, stopping every ten feet or so to clip our safety tethers to metal cables that run alongside.

A half-hour in, our faces slick with sweat, we rested on an outcropping that overlooked a valley carpeted with thick stands of pine and fir. Sheep bleated in a meadow, and a shepherd called to them. We could see the Pasubio Ossuary, a stone tower that holds the remains of 5,000 Italian and Austrian soldiers who fought in these mountains in World War I. The previous night we had slept near the ossuary, along a country road where cowbells clanged softly and lightning bugs blinked in the darkness like muzzle flashes.

Joshua Brandon gazed at the surrounding peaks and took a swig of water. “We’re in one of the most beautiful places in the world,” he said, “and one of the most horrible.”

In the spring of 1916, the Austrians swept down through these mountains. Had they reached the Venetian plain, they could have marched on Venice and encircled much of the Italian Army, breaking what had been a bloody yearlong stalemate. But the Italians stopped them here.

Just below us a narrow road skirted the mountainside, the Italians’ Road of 52 Tunnels, a four-mile donkey path, a third of which runs inside the mountains, built by 600 workers over ten months in 1917.

“A beautiful piece of engineering, but what a wasteful need,” said Chris Simmons, the third member of our group.

Joshua grunted. “Just to pump a bunch of men up a hill to get slaughtered.”

For the next two hours our trail alternated between heady climbing on rock faces and mellow hiking along the mountain ridge. By mid-morning the fog and low clouds had cleared, and before us lay the battlefield, its slopes scored with trenches and stone shelters, the summits laced with tunnels where men lived like moles. We had all served in the military, Chris as a Navy corpsman attached to the Marine Corps, and Joshua and I with the Army infantry. Both Joshua and I had fought in Iraq, but we had never known war like this.

Our path joined the main road, and we hiked through a bucolic scene, blue skies and grassy fields, quiet save for the sheep and the birds. Two young chamois scampered onto a boulder and watched us. What this had once been strained the imagination: the road crowded with men and animals and wagons, the air rank with filth and death, the din of explosions and gunfire.

“Think of how many soldiers walked the same steps we’re walking and had to be carried out,” Joshua said. We passed a hillside cemetery framed by a low stone wall and overgrown with tall grass and wildflowers. Most of its occupants had reached the battlefield in July of 1916 and died over the following weeks. They at least had been recovered; hundreds more still rest where they fell, others blown to pieces and never recovered.

On a steep slope not far from here, an archaeologist named Franco Nicolis helped excavate the remains of three Italian soldiers found in 2011. “Italian troops from the bottom of the valley were trying to conquer the top,” he had told us at his office in Trento, which belonged to Austria-Hungary before the war and to Italy afterward. “These soldiers climbed up to the trench, and they were waiting for dawn. They already had their sunglasses, because they were attacking to the east.”

The sun rose, and the Austrians spotted and killed them.

“In the official documents, the meaning is, ‘Attack failed.’ Nothing more. This is the official truth. But there is another truth, that three young Italian soldiers died in this context,” Nicolis said. “For us, it’s a historical event. But for them, how did they think about their position? When a soldier took the train to the front, was he thinking, ‘Oh my God, I’m going to the front of the First World War, the biggest event ever’? No, he was thinking, ‘This is my life.’”

As Joshua, Chris and I walked through the saddle between the Austrian and Italian positions, Chris spotted something odd nestled in the loose rocks. For nearly two decades he has worked as a professional climbing and skiing guide, and years of studying the landscape as he hikes has honed his eye for detail. In previous days he found a machine gun bullet, a steel ball from a mortar shell and a jagged strip of shrapnel. Now he squatted in the gravel and gently picked up a thin white wedge an inch wide and long as a finger. He cradled it in his palm, unsure what to do with this piece of skull.

**********

The Italians came late to the war. In the spring of 1915, they abandoned their alliance with Austria-Hungary and Germany to join the United Kingdom, France and Russia, hoping for several chunks of Austria at the war’s end. An estimated 600,000 Italians and 400,000 Austrians would die on the Italian Front, many of them in a dozen battles along the Isonzo River in the far northeast. But the front zigzagged 400 miles—nearly as long as the Western Front, in France and Belgium—and much of that crossed rugged mountains, where the fighting was like none the world had ever seen, or has seen since.

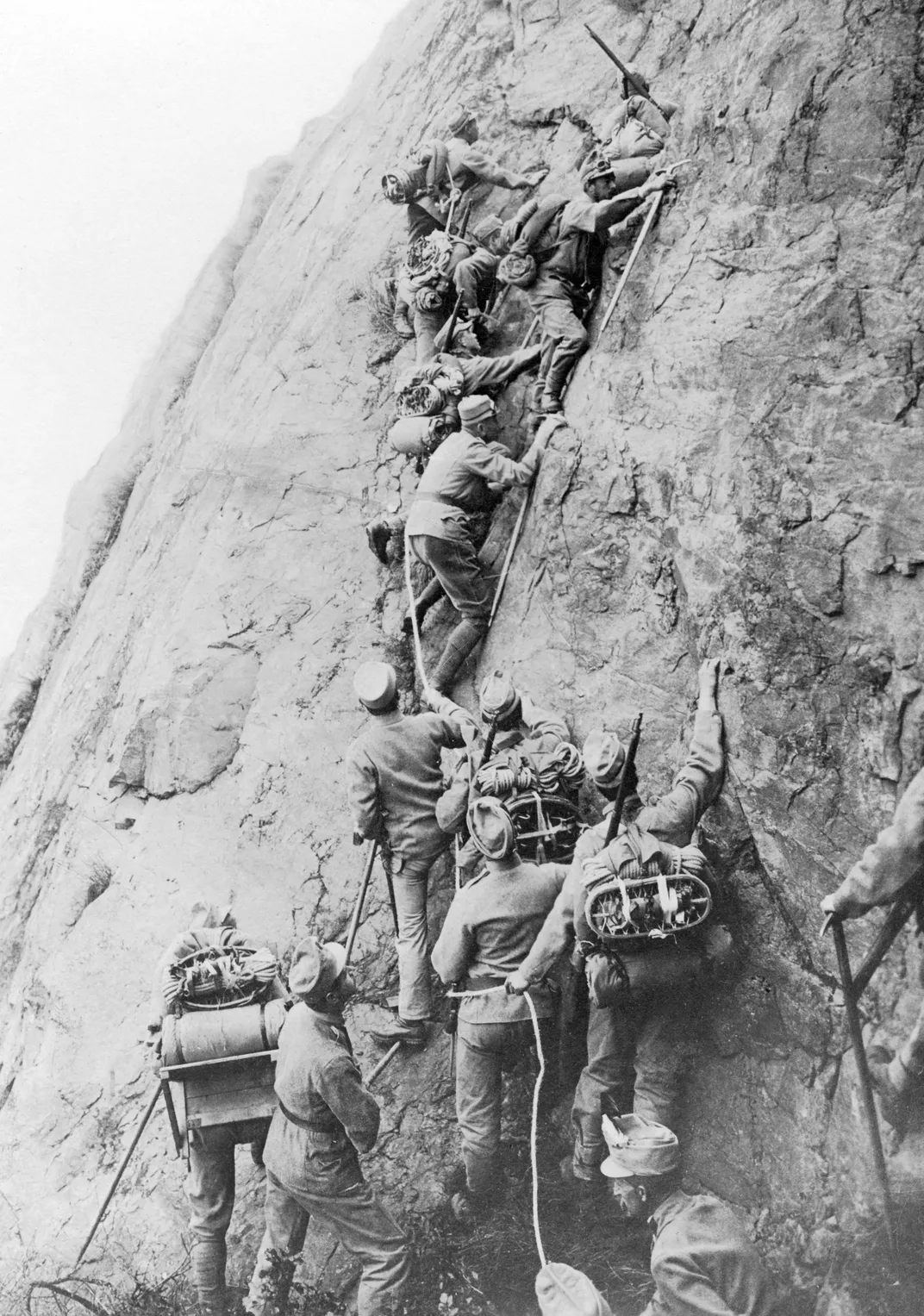

Soldiers had long manned alpine frontiers to secure borders or marched through high passes en route to invasion. But never had the mountains themselves been the battlefield, and for fighting at this scale, with fearsome weapons and physical feats that would humble many mountaineers. As New York World correspondent E. Alexander Powell wrote in 1917: “On no front, not on the sun-scorched plains of Mesopotamia, nor in the frozen Mazurian marshes, nor in the blood-soaked mud of Flanders, does the fighting man lead so arduous an existence as up here on the roof of the world.”

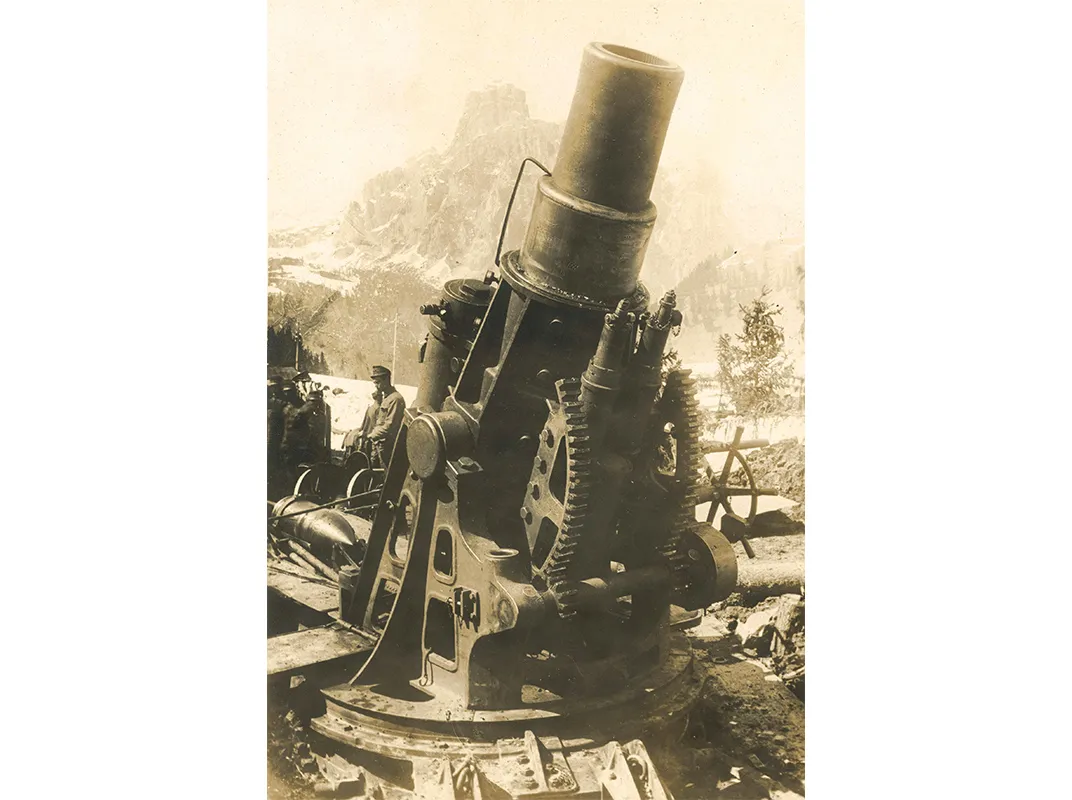

The destruction of World War I overwhelms. Nine million dead. Twenty-one million wounded. The massive frontal assaults, the anonymous soldier, faceless death—against this backdrop, the mountain war in Italy was a battle of small units, of individuals. In subzero temperatures men dug miles of tunnels and caverns through glacial ice. They strung cableways up mountainsides and stitched rock faces with rope ladders to move soldiers onto the high peaks, then hauled up an arsenal of industrial warfare: heavy artillery and mortars, machine guns, poison gas and flamethrowers. And they used the terrain itself as a weapon, rolling boulders to crush attackers and sawing through snow cornices with ropes to trigger avalanches. Storms, rock slides and natural avalanches—the “white death”—killed plenty more. After heavy snowfalls in December of 1916, avalanches buried 10,000 Italian and Austrian troops over just two days.

Yet the Italian mountain war remains today one of the least-known battlefields of the Great War.

“Most people have no idea what happened here,” Joshua said one afternoon as we sat atop an old bunker on a mountainside. Until recently, that included him as well. The little he knew came from Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms, and later reading Erwin Rommel, the famed Desert Fox of World War II, who had fought in the Italian Alps as a young officer in World War I.

Joshua, who is 38, studied history at the Citadel and understands the theory of war, but he also served three tours in Iraq. He wears a beard now, trimmed short and speckled with gray, and his 5-foot-9 frame is wiry, better for hauling himself up steep cliffs and trekking through the wilderness. In Iraq he had bulked to nearly 200 pounds, thick muscle for sprinting down alleyways, carrying wounded comrades and, on one afternoon, fighting hand-to-hand. He excelled in battle, for which he was awarded the Silver Star and two Bronze Stars with Valor. But he struggled at home, feeling both alienated from American society and mentally wrung out from combat. In 2012 he left the Army as a major and sought solace in the outdoors. He found that rock climbing and mountaineering brought him peace and perspective even as it mimicked the best parts of his military career: some risk, trusting others with his life, a shared sense of mission.

Once he understood the skill needed to travel and survive in mountains, he looked at the alpine war in Italy with fresh eyes. How, he wondered, had the Italians and Austrians lived and fought in such unforgiving terrain?

Chris, who is 43, met Joshua four years ago at a rock gym in Washington State, where they both live, and now climb together often. I met Joshua three years ago at an ice-climbing event in Montana and Chris a year later on a climbing trip in the Cascade Mountains. Our shared military experience and love of the mountains led us to explore these remote battlefields, like touring Gettysburg if it sat atop a jagged peak at 10,000 feet. “You can’t get to many of these fighting positions without using the skills of a climber,” Joshua said, “and that allows you to have an intimacy that you might not otherwise.”

**********

The Italian Front

Italy entered World War I in May 1915, turning on its ex-ally Austria-Hungary. The fighting soon devolved into trench warfare in the northeast and alpine combat in the north. Hover over the icons below for information on major battles.

Storming the Castelletto

**********

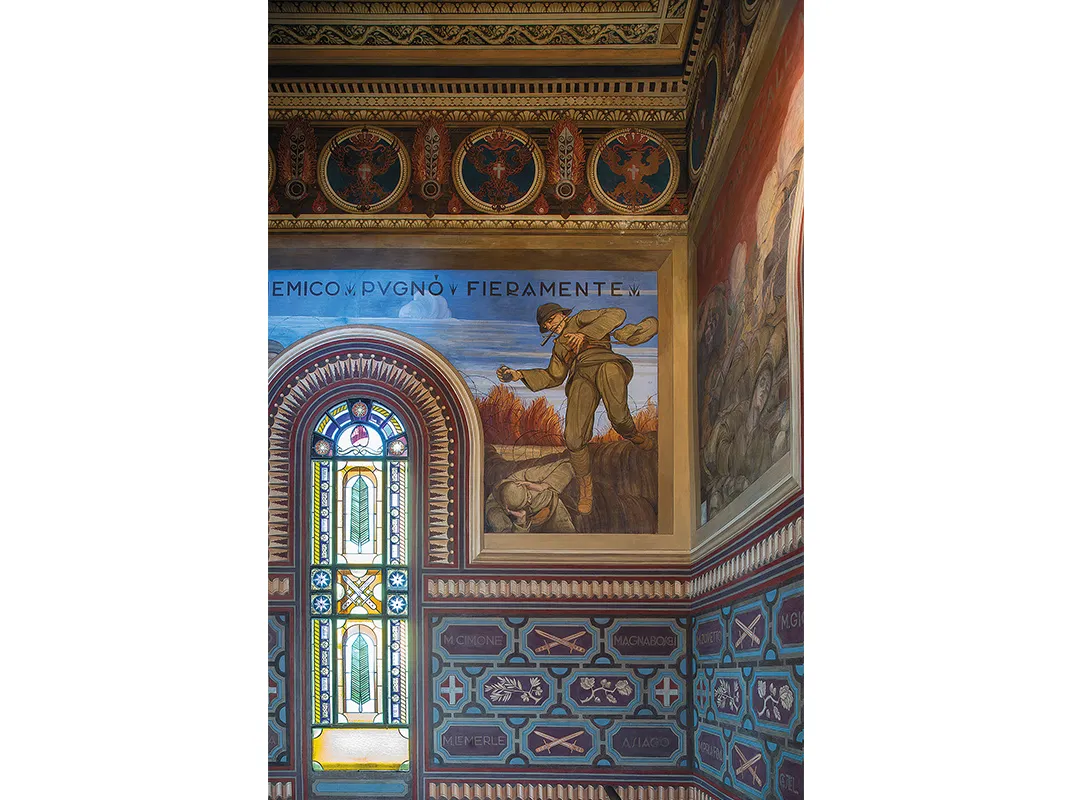

If the Italian Front is largely forgotten elsewhere, the war is ever-present across northern Italy, etched into the land. The mountains and valleys are lined with trenches and dotted with stone fortresses. Rusted strands of barbed wire sprout from the earth, crosses built from battlefield detritus rise from mountaintops, and piazza monuments celebrate the heroes and the dead.

“We are living together with our deep history,” Nicolis, the researcher, told us. “The war is still in our lives.” Between climbs to isolated battlefields, we had stopped in Trento to meet with Nicolis, who directs the Archaeological Heritage Office for Trentino Province. We had spent weeks before our trip reading histories of the war in Italy and had brought a stack of maps and guidebooks; we knew what had happened and where, but from Nicolis we sought more on who and why. He is a leading voice in what he calls “grandfather archaeology,” a consideration of history and memory told in family lore. His grandfather fought for Italy, his wife’s grandfather for Austria-Hungary, a common story in this region.

Nicolis, who is 59, specialized in prehistory until he found World War I artifacts while excavating a Bronze Age smelting site on an alpine plateau a decade ago. Ancient and modern, side by side. “This was the first step,” he said. “I began to think about archaeology as a discipline of the very recent past.”

By the time he broadened his focus, many World War I sites had been picked over for scrap metal or souvenirs. The scavenging continues—treasure hunters recently used a helicopter to hoist a cannon from a mountaintop—and climate change has hastened the revelation of what remains, including bodies long buried in ice on the highest battlefields.

On the Presena Glacier, Nicolis helped recover the bodies of two Austrian soldiers discovered in 2012. They had been buried in a crevasse, but the glacier was 150 feet higher a century ago; as it shrank, the men emerged from the ice, bones inside tattered uniforms. The two skulls, both found amid blond hair, had shrapnel holes, the metal still rattling around inside. One of the skulls had eyes as well. “It was as if he was looking at me and not vice versa,” Nicolis said. “I was thinking about their families, their mothers. Goodbye my son. Please come back soon. And they completely disappeared, as if they never existed. These are what I call the silent witnesses, the missing witnesses.”

At an Austrian position in a tunnel on Punta Linke, at nearly 12,000 feet, Nicolis and his colleagues chipped away and melted the ice, finding, among other artifacts, a wooden bucket filled with sauerkraut, an unsent letter, newspaper clippings and a pile of straw overshoes, woven in Austria by Russian prisoners to shield soldiers’ feet from the bitter cold. The team of historians, mountaineers and archaeologists restored the site to what it might have been a century ago, a sort of living history for those who make the long journey by cable car and a steep hike.

“We cannot just speak and write as archaeologists,” Nicolis said. “We have to use other languages: narrative, poetry, dance, art.” On the curved white walls of the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rovereto, battlefield artifacts found by Nicolis and his colleagues were presented without explanation, a cause for contemplation. Helmets and crampons, mess kits, hand grenades and pieces of clothing hang in vertical rows of five items, each row set above a pair of empty straw overshoes. The effect was stark and haunting, a soldier deconstructed. “When I saw the final version,” Nicolis told us, “I said, ‘Oh my God, this means I am present. Here I am. This is a person.’ ”

When Joshua stood before the exhibit, he thought of his own dead, friends and soldiers who’d served under him, each memorialized at ceremonies with a battle cross: a rifle with bayonet struck in the ground muzzle-down between empty combat boots, a helmet atop the rifle butt. Artifacts over empty shoes. I am present. Here I am.

**********

The sky threatened rain, and low clouds wrapped us in a chilly haze. I stood with Joshua on a table-size patch of level rock, halfway up a 1,800-foot face on Tofana di Rozes, an enormous gray massif near the Austrian border. Below us a wide valley stretched to a dozen more steep peaks. We had been on the wall six hours already, and we had another six to go.

As Chris climbed 100 feet overhead, a golf ball-size chunk of rock popped loose and zinged past us with a high-pitched whir like whizzing shrapnel. Joshua and I traded glances and chuckled.

The Tofana di Rozes towers over a 700-foot-tall blade of rock called the Castelletto, or Little Castle. In 1915 a single platoon of Germans occupied the Castelletto, and with a machine gun they had littered the valley with dead Italians. “The result was startling: In all directions wounded horses racing, people running from the forest, frightened to death,” a soldier named Gunther Langes recalled of one attack. “The sharpshooters caught them with their rifle scopes, and their bullets did a great job. So an Italian camp bled to death at the foot of the mountain.” More and better-armed Austrians replaced the Germans, cutting off a major potential supply route and muddling Italian plans to push north into Austria-Hungary.

Conquering the Castelletto fell to the Alpini, Italy’s mountain troops, known by their dashing felt hats adorned with a black raven feather. One thought was that if they could climb the Tofana’s face to a small ledge hundreds of feet above the Austrians’ stronghold, they could hoist up a machine gun, even a small artillery piece, and fire down on them. But the route—steep, slick with runoff and exposed to enemy fire—was beyond the skill of most. The assignment went to Ugo Vallepiana and Giuseppe Gaspard, two Alpini with a history of daring climbs together. Starting in a deep alcove, out of Austrian view, they worked up the Tofana di Rozes, wearing hemp-soled shoes that offered better traction than their hobnailed boots and dampened the sounds of their movements.

We were climbing a route not far from theirs, with Chris and Joshua alternating the lead. One would climb up about 100 feet, and along the way slide special cams into cracks and nooks, then clip the protective gear to the rope with a carabiner, a metal loop with a spring-loaded arm. In other places, they clipped the rope to a piton, a steel wedge with an open circle at the end pounded into the rock by previous climbers. If they slipped, they might drop 20 feet instead of hundreds, and the climbing rope would stretch to absorb a fall.

Vallepiana and Gaspard had none of this specialized equipment. Even the carabiner, a climbing essential invented shortly before the war, was unknown to most soldiers. Instead, Gaspard used a technique that makes my stomach quiver: Each time he hammered in a piton, he untied the rope from around his waist, threaded it through the metal loop, and retied it. And their hemp ropes could just as easily snap as catch a fall.

As we neared the top of our climb, I hoisted myself onto a four-foot lip and passed through a narrow chute to another ledge. Joshua, farther ahead and out of sight, had anchored himself to a rock and pulled in my rope as I moved. Chris was 12 feet behind me, and still on a lower level, exposed from the chest up.

I stepped onto the ledge and felt it give way.

“Rock!” I shouted, and snapped my head to see my formerly solid step now broken free and cleaved in two, crashing down the chute. One piece smashed into the wall and stopped, but the other half, maybe 150 pounds and big as a carry-on suitcase, plowed toward Chris. He threw out his hands and stopped the rock with a grunt and a wince.

I scrambled down the chute, braced my feet on either side of the rock and held it in place as Chris climbed past me. I let go, and the chunk tumbled down the mountainside. A strong whiff of ozone from the fractured rocks hung in the air. He made a fist and released his fingers. Nothing broken.

My poorly placed step could have injured or killed him. But I imagine the two Alpini would have thought our near-miss trivial. On a later climbing mission with Vallepiana, Gaspard was struck by lightning and nearly died. This climb almost killed him, too. As he strained for a handhold at a tricky section, his foot slipped and he plummeted 60 feet—into a small snowbank, remarkable luck in vertical terrain. He climbed on, and into the Austrians’ view. A sniper shot him in the arm, and Austrian artillery across the valley fired shells into the mountain overhead, showering him and Vallepiana with jagged metal shards and shattered rock.

Still, the two reached the narrow ledge that overlooked the Austrians, a feat that earned them Italy’s second-highest medal for valor. Then, in what certainly seems an anticlimax today, the guns the Italians hauled up there proved less effective than they had hoped.

But the Italians’ main effort was even more daring and difficult, as we would soon see.

**********

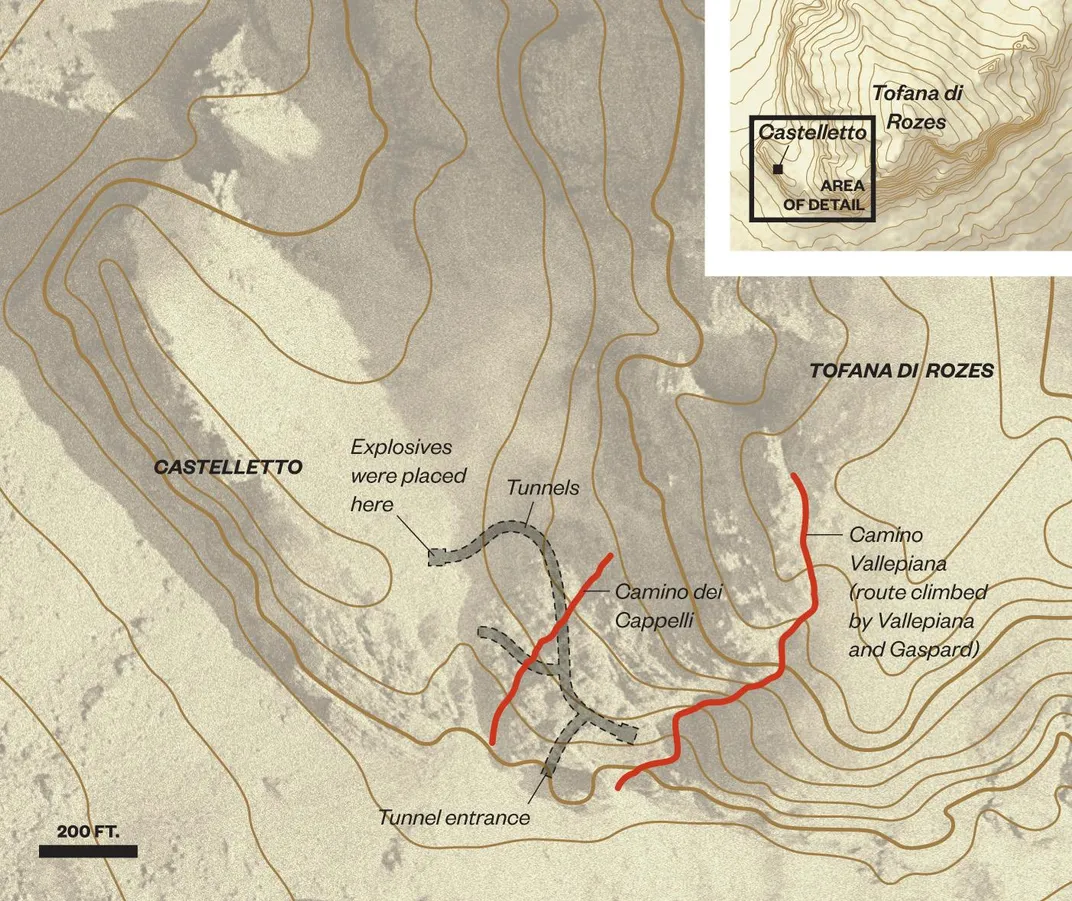

In a region of magnificent peaks, the Castelletto is not much to behold. The squat trapezoid juts up 700 feet to a line of sharp spires, but is dwarfed by the Tofana di Rozes, which rises an additional 1,100 feet just behind it. During our climb high on the Tofana wall we couldn’t see the Castelletto, but now it loomed before us. We sat in an old Italian trench built from limestone blocks in the Costeana Valley, which runs west from the mountain town of Cortina d’Ampezzo. If we strained our eyes, we could see tiny holes just below the Castelletto’s spine—windows for caverns the Austrians and Germans carved soon after Italy declared war in 1915.

From these tunnels and rooms, which offered excellent protection from artillery fire, their machine gunners cut down anyone who showed himself in this valley. “You can imagine why this was such a nightmare for the Italians,” Joshua said, looking up at the fortress. In the struggle for the Castelletto we found in microcosm the savagery and intimacy, the ingenuity and futility of this alpine fighting.

The Italians first tried to climb it. On a summer night in 1915, four Alpini started up the steep face, difficult in daylight, surely terrifying at night. Lookouts perched on the rocky spires heard muffled sounds in the darkness below and stepped to the edge, eyes and ears straining. Again, sounds of movement, metal scraping against rock and labored breathing. A sentry leveled his rifle and, as the lead climber crested the face and pulled himself up, fired. The men were so close the muzzle flash lit the Italian’s face as he pitched backward. Thumps as he crashed into the climbers below him, then screams. In the morning the soldiers looked down on four crumpled bodies sprawled on the slope far below.

The Italians next tried the steep and rocky gully between the Castelletto and the Tofana, using a morning fog as cover. But the fog thinned enough to reveal specters advancing through the mist, and machine gunners annihilated them. In the autumn of 1915 they attacked from three sides with hundreds of men—surely they could overwhelm a platoon of defenders—but the slopes only piled deeper with dead.

The Alpini reconsidered: If they couldn’t storm the Castelletto, maybe they could attack from within.

Just around the corner from the Castelletto and beyond the Austrians’ field of view, Joshua, Chris and I scaled 50 feet of metal rungs running beside the original wooden ladders, now broken and rotting. At an alcove on the Tofana wall, we found the tunnel opening, six feet wide and six feet high, and the darkness swallowed our headlamp beams. The path gains hundreds of feet as it climbs through the mountain, steep and treacherous on rock made slimy with water and mud. Fortunately for us, it’s now a via ferrata. We clipped our safety harnesses onto metal rods and cables fixed to the walls after the war.

The Alpini started with hammers and chisels in February of 1916 and pecked out just a few feet a day. In March they acquired two pneumatic drills driven by gas-powered compressors, hauled up the valley in pieces through the deep snow. Four teams of 25 to 30 men worked in continuous six-hour shifts, drilling, blasting and hauling rock, extending the tunnel by 15 to 30 feet each day. It would eventually stretch more than 1,500 feet.

The mountain shuddered with internal explosions, sometimes 60 or more a day, and as the ground shook beneath them the Austrians debated the Italians’ intent. Perhaps they would burst through the Tofana wall and attack across the rocky saddle. Or emerge from below, another suggested. “One night, when we’re sleeping, they will jump out of their hole and cut our throats,” he said. The third theory, to which the men soon resigned themselves, was the most distressing: The Italians would fill the tunnel with explosives.

Indeed, deep in the mountain and halfway to the Castelletto, the tunnel split. One branch burrowed beneath the Austrian positions, where an enormous bomb would be placed. The other tunnel spiraled higher, and would open on the Tofana face, at what the Italians figured would be the bomb crater’s edge. After the blast, Alpini would pour through the tunnel and across the crater. Dozens would descend rope ladders from positions high on the Tofana wall, and scores more would charge up the steep gully. Within minutes of the blast, they would finally control the Castelletto.

**********

The Austrian platoon commander, Hans Schneeberger, was 19 years old. He arrived on the Castelletto after an Italian sniper killed his predecessor. “I would gladly have sent someone else,” Capt. Carl von Rasch told him, “but you are the youngest, and you have no family.” This was not a mission from which Schneeberger, or his men, were expected to return.

“It’s better that you know how things stand up here: They do not go well at all,” von Rasch said during a late-night visit to the outpost. “The Castelletto is in an impossible situation.” Nearly surrounded, under incessant artillery bombardment and sniper fire, with too few men and food running low. Throughout the valley, the Italians outnumbered the Austrians two to one; around the Castelletto it was perhaps 10 or 20 to one. “If you do not die from hunger or cold,” von Rasch said, “then someday soon you will be blown into the air.” Yet Schneeberger and his few men played a strategic role: By tying up hundreds of Italians, they could ease pressure elsewhere on the front.

“The Castelletto must be held. It will be held to the death,” von Rasch told him. “You must stay up here.”

In June, Schneeberger led a patrol onto the face of the Tofana di Rozes to knock out an Italian fighting position and, if possible, to sabotage the tunneling operation. After precarious climbing, he pulled himself onto a narrow lip, pitched an Alpini over the edge and stormed into an outpost on the cliffside, where a trapdoor led to Italian positions below. His trusted sergeant, Teschner, nodded at the floor and smiled. He could hear Alpini climbing up rope ladders to attack.

A few days earlier, a half-dozen Austrians standing guard on the Tofana wall had started chatting with nearby Alpini, which led to a night of shared wine. Teschner did not share this affinity for the Alpini. One Sunday morning, when singing echoed off the rock walls from the Italians holding Mass below, he had rolled heavy spherical bombs down the gully between the Castelletto and the Tofana to interrupt the service.

Now in the small shack he drew his bayonet, threw open the trapdoor and shouted, “Welcome to heaven, dogs!” as he sliced through the rope ladders. The Alpini screamed, and Teschner laughed and slapped his thigh.

The attack earned Schneeberger Austria-Hungary’s highest medal for bravery, but he and his men learned nothing new about the tunneling, or how to stop it. Between daily skirmishes with Italian sentries, they pondered everything they would miss—a woman’s love, adventures in far-off lands, even lying bare-chested in the sun atop the Castelletto and daydreaming about a life after the war. Yet the explosions provided an odd comfort: As long as the Italians drilled and blasted, the mine wasn’t finished.

Then the Austrians intercepted a transmission: “The tunnel is ready. Everything is perfect.”

With the mountain silent and the blast imminent, Schneeberger lay on his bunk and listened to mice skitter across the floor. “Strange, everyone knows that sooner or later he will have to die, and one hardly thinks about it,” he wrote. “But when death is certain, and one even knows the deadline, it eclipses everything: every thought and feeling.”

He gathered his men and asked if any wanted to leave. None stepped forward. Not Latschneider, the platoon’s oldest at 52, or Aschenbrenner, with eight children at home. And their wait began.

“Everything is like yesterday,” Schneeberger wrote on July 10, “except that another 24 hours have passed and we are 24 hours closer to death.”

**********

Lt. Luigi Malvezzi, who led the tunnel digging, had asked for 77,000 pounds of blasting gelatin—nearly half of Italy’s monthly production. High command balked at the request, but was swayed by a frustrating detail: The Italians had pounded the Castelletto with artillery for nearly a year, to little effect. So for three days, Italian soldiers had ferried crates of explosives up the tunnel to the mine chamber, 16 feet wide, 16 feet long, and nearly 7 feet high. Through fissures in the rock, they could smell the Austrians’ cooking. They packed the chamber full, then backfilled 110 feet of the tunnel with sandbags, concrete and timber to direct the blast upward with full force.

At 3:30 a.m. on July 11, as Hans Schneeberger lay on his bunk mourning a friend who’d just been killed by a sniper’s bullet, Malvezzi gathered with his men on the terrace leading to the tunnel and flipped the detonator switch. “One, two, three seconds passed in a silence so intense that I heard the sharp ping of the water dripping from the roof of the chamber and striking the pool it had formed below,” Malvezzi wrote.

Then the mountain roared, the air filled with choking dust, and Schneeberger’s head seemed ready to burst. The blast pitched him out of bed, and he stumbled from his room and into a fog of smoke and debris and stood at the lip of a massive crater that had been the southern end of the Castelletto. In the darkness and rubble, his men screamed.

The fight for this wedge of rock had gained such prominence for Italy that King Victor Emmanuel III and Gen. Luigi Cadorna, the army chief of staff, watched from a nearby mountain. A fountain of flame erupted in the darkness, the right-hand side of the Castelletto shuddered and collapsed, and they cheered their success.

But the attack proved to be a fiasco. The explosion consumed much of the nearby oxygen, replacing it with carbon monoxide and other toxic gases that swamped the crater and pushed into the tunnel. Malvezzi and his men charged through the tunnel to the crater and collapsed, unconscious. Several fell dead.

Alpini waiting high on the Tofana wall couldn’t descend because the explosion had shredded their rope ladders. And in the steep gully between the Castelletto and the Tofana, the blast fractured the rock face. For hours afterward huge boulders peeled off like flaking plaster and crashed down the gully, crushing attacking soldiers and sending the rest scurrying for cover.

**********

We traced the Alpinis’ route through the tunnel, running our hands along walls slick with seeping water and scarred with grooves from the tunnelers’ drill bits. We passed the tunnel branch to the mine chamber and spiraled higher into the mountain, clipping our safety tethers to metal cables bolted to the walls.

Around a sharp bend, the darkness gave way. Along with the main detonation, the Italians triggered a small charge that blasted open the final few feet of this attack tunnel, until then kept secret from the Austrians. Now Joshua stepped from the tunnel, squinted in the daylight, and looked down on what had been the southern end of the Castelletto. He shook his head in awe.

“So this is what happens when you detonate 35 tons of explosives under a bunch of Austrians,” he said. Joshua had been near more explosions than he can remember—hand grenades, rockets, roadside bombs. In Iraq a suicide car bomber rammed into his outpost as he slept, and the blast threw him from his bed, just as it had Schneeberger. “But that was nowhere near the violence and landscape-altering force of this explosion,” he said.

We scrambled down a steep gravel slope and onto a wide snowfield at the crater’s bottom. The blast had pulverized enough mountain to fill a thousand dump trucks and tossed boulders across the valley. It killed 20 Austrians asleep in a shack above the mine and buried the machine guns and mortars.

It spared Schneeberger and a handful of his men. They scrounged a dozen rifles, 360 bullets and a few grenades, and from the crater’s edge and the intact outposts, started picking off Italians again.

“Imagine losing half your platoon instantly and having that will to push on and defend what you’ve got,” Joshua said. “Just a few men holding off an entire battalion trying to assault up through here. It’s madness.”

**********

I felt a strange pulse of anticipation as we climbed out of the crater and onto the Castelletto. At last, the battle’s culmination. Chris disappeared in the jumble of rock above us. A few minutes later he let out a happy yelp: He’d found an entrance to the Austrian positions.

We ducked our heads and stepped into a cavern that ran 100 feet through the Castelletto’s narrow spine. Water dripped from the ceiling and pooled in icy puddles. Small rooms branched off the main tunnel, some with old wooden bunks. Windows looked out on the valley far below and peaks in the distance.

Such beauty was hard to reconcile with what happened a century ago. Chris had pondered this often throughout the week. “You just stop and appreciate where you’re at for the moment,” he said. “And I wonder if they had those moments, too. Or if it was all terror, all the time.” Emotion choked his voice. “When we look across it’s green and verdant. But when they were there, it was barbed wire and trenches and artillery shells screaming around. Did they get to have a moment of peace?”

Joshua felt himself pulled deeply into the combatants’ world, and this startled him. “I have more in common with these Austrians and Italians who are buried under my feet than I do with a lot of contemporary society,” he said. “There’s this bond of being a soldier and going through combat,” he said. “The hardship. The fear. You’re just fighting for survival, or fighting for the people around you, and that transcends time.”

The Austrians’ and Italians’ losses and gains in these mountains made little difference. The alpine war was a sideshow to the fighting on the Isonzo, which was a sideshow to the Western and Eastern Fronts. But for the soldier, of course, all that matters is the patch of ground that must be taken or held, and whether he lives or dies in doing that.

The day after the blast, the Italians hoisted machine guns onto the Tofana and raked the Castelletto, killing more Austrians. The rest scurried into the tunnels where we now sat. Schneeberger scribbled a note on his situation—33 dead, position nearly destroyed, reinforcements badly needed—and handed it to Latschneider.

“You only die once,” the platoon’s old man said, then crossed himself and sprinted down the wide scree slope between the Castelletto and the Tofana, chased by machine gun bullets. He ran across the valley, delivered the note to Captain von Rasch—and dropped dead from the effort.

Reinforcements came that night, and Schneeberger marched his few surviving men back to the Austrian lines. The Italians charged through the crater a few hours later, lobbed tear gas into the tunnels and captured the southern end of the Castelletto and most of the relief platoon. A few Austrians held the northern end for several days, then withdrew.

In the Austrian camp, Schneeberger reported to von Rasch, who stood at his window with stooped shoulders and wet eyes, hands clasped behind his back.

“It was very hard?” he asked.

“Sir,” Schneeberger said.

“Poor, poor boy.”

Related Reads

The Guns of August: The Outbreak of World War I

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/aa/d0aa3c5e-66a6-478c-8fc9-ed841d5852f7/jun2016_b15_dolomites.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/80/a0/80a05a49-7550-46fb-b8de-6be29daead45/jun2016_b06_dolomites.jpg)