Motopia: A Pedestrian Paradise

Visit the futuristic town where drivers and non-drivers live in perfect harmony

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201212060251571960-ctwt-motopia-470x251.jpg)

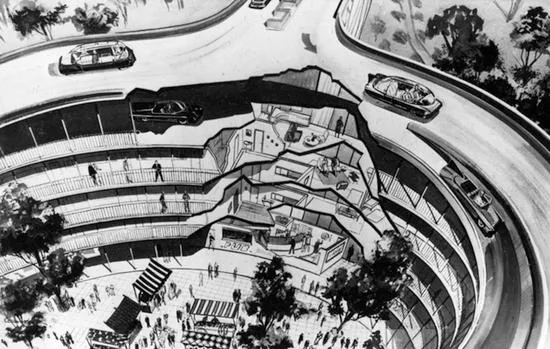

“No person will walk where automobiles move,” is how British architect Geoffrey Alan Jellicoe described his town of the future, “and no car can encroach on the area sacred to the pedestrian.”

Jellicoe was talking to the Associated Press in 1960 about his vision for a radically new kind of British town—a town where the bubble-top cars of tomorrow moved freely on elevated streets, and the pedestrian zipped around safely on moving sidewalks. For a town whose main selling point was the freedom to not worry about getting hit by cars, it would have a rather strange name: Motopia.

Planned for construction about 17 miles west of London with an estimated cost of about $170 million, Motopia was a bold—if somewhat impractical plan—for a city built from the ground up. The town was envisioned as being able to have a population of 30,000, all living in a grid-pattern of buildings with an expanse of rooftop motorways in the sky. There would be schools, shops, restaurants, churches and theaters all resting on a total footprint of about 1,000 acres.

Motopia was to be a town with no heavy industry; a “dormitory community” where people largely found work elsewhere. The community was imagined as modern but tranquil; a town where accepting the bold new postwar future didn’t mean giving up the more peaceful aspects of daily living. But what about all the noise from the roads above? The planners were quick to point out that a special kind of insulation would be used to block out any of the noise from all the cars roaring along on your roof.

“In this town we are separating the biological elements from the mechanical,” Jellicoe told the Associated Press at the time. “The secret is as simple as that.”

Britain passed the New Towns Act of 1946 after World War II, which gave the government the power to quickly designate land for new development. Even before fighting had ceased the British began planning how they might rebuild London, while funneling population to less dense towns just outside the city. London had been battered during the war and the rapid development of towns was necessary to accomodate the overspill of population. Fourteen new towns were established between 1946 and 1950 after the passage of the New Towns Act, but according to Guy Ortolano at New York University, these modestly designed communities didn’t impress the more avant-garde planners of the day.

As Ortolano explains in his 2011 paper, “Planning the Urban Future in 1960s Britain,” just one new town was established by Conservative British governments in the 1950s. But the baby boom sparked new interest in town development as the ’60s arrived.

The September 25, 1960 edition of Arthur Radebaugh‘s Sunday comic strip “Closer Than We Think” was devoted to Jellicoe’s Motopia and gave readers in North America a splashy and colorful peek at the city of tomorrow. Radebaugh’s cars were less bubble-top and more mid-century Detroit-tailfin than his British designer counterparts, which was only natural given that Radebaugh was based in Detroit. He also made the moving sidewalk a much more prominent part of his illustrations than the designs coming from Jellicoe and his team.

Ortolano explains in his paper that between 1961 and 1970 new town development in Britain became much more ambitious and experimental, incorporating the private automobile, monorail and even hovercraft as more central characters in its designs. But Motopia was not to be, despite the rosey predictions of Jellicoe.

“Motopia is not only possible, but it is practical because it is economical,” Jellicose told the Associate Press. “The dwellings would be no more expensive than housing for a similar population in tall buildings, such as those used by the London City Council in some of its developments.”

Jellicoe described the futuristic city of Motopia as like “living in a park,” which again, begs the question of the name. But this wasn’t Jellicoe’s only vision for the city of the future. As the January 30, 1960 issue of Stars and Stripes explained, Jellicoe had many ideas for the British landscape of tomorrow: ”‘Soho in 2000,’ a plan for ripping out the famed old section of London and rebuilding it for 20th Century life; a High Market shopping center for the small industrial cities of the Midlands that don’t have adequate shopping facilities at present; and St. John’s Circus, a modern development south of London that would utilize a huge traffic circle and heliports.”

Alas, none of these futuristic visions were realized, but you can watch a short newsreel of Jellicoe’s plans for Motopia at British Pathe.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)