Moving Sidewalks Before The Jetsons

The public’s fascination with the concept of “movable pavement” extends back more than 130 years

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1956-goodyear-1999-ny-subway-sm.jpg)

I recently heard someone assert that the 1962/63 TV cartoon show “The Jetsons” invented the concept of the moving sidewalk. While the Jetsons family certainly did a great deal to plant the idea of the moving walkway into the public consciousness, the concept is much older than 1962.

Today, moving sidewalks are largely relegated to airports and amusement parks, but there were big plans for the technology in the 19th and 20th centuries. In 1871 inventor Alfred Speer patented a system of moving sidewalks that he thought would revolutionize pedestrian travel in New York City. Sometimes called the “movable pavement,” his system would transport pedestrians along a series of three belts running parallel to each other, each successively faster than the next. When Mr. Speer explained his vision to Frank Leslie’s Weekly in 1874 it even included a few enclosed “parlor cars” every 100 feet or so — some cars with drawing rooms for ladies, and others for men to smoke in.

An 1890 issue of Scientific American explained Speer’s system:

These belts were to be made up of a series of small platform railway cars strung together. The first line of belts was to run at a slow velocity, say 3 miles per hour, and upon this slow belt of moving pavement, passengers were expected to step without difficulty. The next adjoining belt was intended to have a velocity of 6 miles per hour, but its speed, in reference to the first belt, would be only 3 miles per hour. Each separate line of belt was thus to have a different speed from the adjacent one; and thus the passenger might, by stepping from one platform to another, increase or diminish his rate of transit at will. Seats were to be placed at convenient points on the traveling platforms.

Though a very forward-thinking French engineer by the name of Eugene Henard submitted plans to include a moving platform system for the 1889 Paris Fair, those plans fell through and the first electric moving sidewalk was built for the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The moving sidewalk featured benches for passengers and cost a nickel, but was undependable and prone to breaking down. As the Western Electrician noted in the lead up to the Exposition, there was a contract for 4,500 feet of movable sidewalk designed primarily to carry those passengers arriving by steamboats. When it was operating, people could get off the boats and travel on the moving sidewalk 2,500 feet down the pier, delivered to the shore and the Exposition entrance.

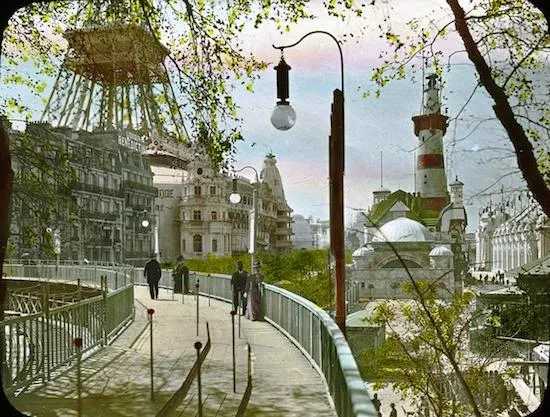

The 1900 Paris Exposition had its own moving walkway, which was quite impressive. Thomas Edison sent one of his producers, James Henry White, to the Exposition and Mr. White shot at least 16 movies while at the Exposition. He had brought along a new panning-head tripod that gave his films a newfound sense of freedom and flow. Watching the film, you can see children jumping into frame and even a man doffing his cap to the camera, possibly aware that he was being captured by an exciting new technology while a fun novelty of the future chugs along under his feet.

The New York Observer reported on the 1900 Paris Exposition in a series of letters from a man who simply went by the name Augustus. The October 18, 1900 issue of the newspaper included this correspondence describing the new mode of travel:

From this part of the fair it is possible to proceed to a distant exhibition which is placed in what is called the Champs de-Mars, without going out of the gates, by means of a travelling sidewalk or a train of electric cars. Thousands avail themselves of these means of transportation. The former is a novelty. It consists of three elevated platforms, the first being stationary, the second moving at a moderate rate of speed, and the third at the rate of about six miles an hour. The moving sidewalks have upright posts with knobbed tops by which one can steady himself in passing to or from the platforms. There are occasional seats on these platforms, and the circuit of the Exposition can be made with rapidity and ease by this contrivance. It also affords a good deal of fun, for most of the visitors are unfamiliar with this mode of transit, and are awkward in its use. The platform runs constantly in one direction, and the electric cars in the opposite.

The hand-colored photographs below are from the Brooklyn Museum and show the moving sidewalk at the Paris Expo in 1900.

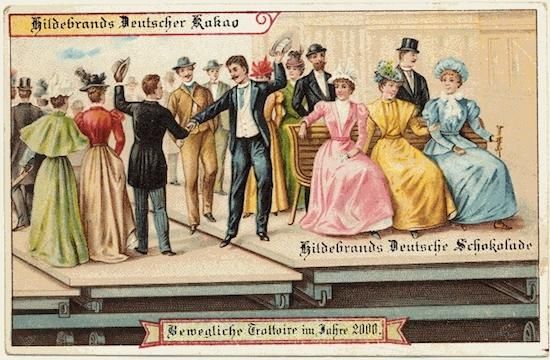

Likely inspired by the 1900 Paris Expo, this moving sidewalk of the year 2000 was one in a series of future-themed cards released in 1900 by the German chocolate company Hildebrands.

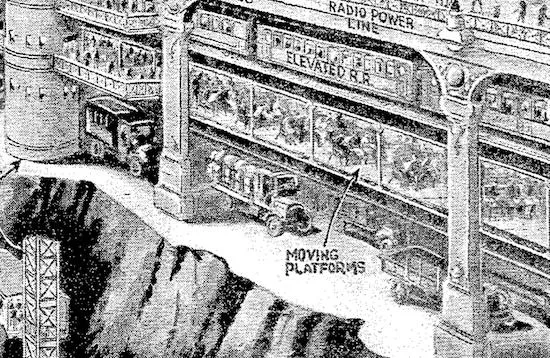

The moving sidewalk again came into vogue in the 1920s when the city of the future was imagined as something sleek and automated. The February 8, 1925 issue of the Texas newspaper, the San Antonio Light, featured predictions about the year 1975 from the great prognosticator Hugo Gernsback. The article included a prediction for the moving sidewalk of fifty years hence:

Below the elevated railway we have continuous moving platforms. There will be three such moving platforms alongside of each other. The first platform will move only a few miles per hour, the second at eight or ten miles per hour, and the third at twelve or fifteen miles per hour.

You step upon the slowest moving one from terra firma and move to the faster ones and take your seat. Then arriving at your station, you can either take the lift to the top platform or else you can get off upon the “elevated level” and take the fast train there. which stops only every thirty or forty blocks. Or, if you do not wish this, you can descend by the same elevator down to the local subway.

The 1930s and 40s largely saw the world much more pre-occupied with the Great Depression and World War II respectively, but postwar American companies really pushed the idea of moving sidewalks into high gear. Goodyear was at the front of that effort and in the early 1950s drew up different plans for the use of moving sidewalks in stadium parking lots and a radically re-imagined New York subway system.

The May, 1951 issue of Popular Science explained to readers that the moving sidewalk was like an “escalator running flat.” That article used the same Goodyear publicity illustrations that were later used in the 1956 book 1999: Our Hopeful Future by Victor Cohn. Cohn describes Goodyear’s vision of a pedestrian-friendly moving sidewalk system:

For example, why not conveyor belts, huge moving sidewalks, to zip pedestrians along from place to place? Such conveyor-belt “speedwalks,” not supersonic but steady moving (in contrast to busses or taxicabs) may be just the device to come to our rescue.

Today, Goodyear makes the moving sidewalks you can find at the Disney theme parks. These moving sidewalks will be familiar to anyone who has been on Space Mountain at the Magic Kingdom in Walt Disney World or a great number of dark rides at Disneyland, where they allow people to get on and off rides with ease. This practical use of a moving sidewalk in a theme park is not unlike the picture above of Goodyear’s New York subway system of the future.

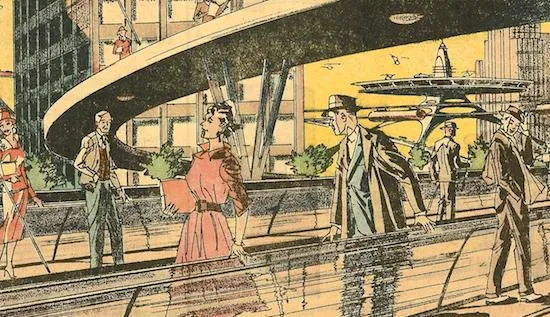

Goodyear’s moving sidewalks were also featured in the June 7, 1959 edition of Arthur Radebaugh‘s Sunday comic Closer Than We Think. The comic explains that the moving sidewalk — which Goodyear imagined would be used to transport sports fans from a stadium to the parking lot — was indeed built at the Houston Coliseum:

The large malls planned for tomorrow’s metropolitan centers will not be tied up with vehicular traffic. Shoppers and sight-seers will be transported by mobile sidewalks that closely resemble giant conveyer belts. Parcels to be delivered will be carried by overhead rail to trucks on the area’s perimeter.

Passenger-carrying belts are already in use. Goodyear has built one connecting nearby rail terminals in Jersey City, N.J. Another has been set up by Goodrich and it runs from the entrance of the Houston Coliseum to the parking lot.

One of the longest such devices is the two-mile installation at the site of Trinity Dam in California. It was designed to facilitate the movement of material during construction of the dam.

Well, that about takes us to 1962 and as you can well see, the Jetsons had almost 100 years of futuristic moving sidewalks to draw from.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)