Mr. Lincoln’s Washington

The house where the conspirators hatched their heinous plot now serves sushi, and the yard where they were hanged is a tennis court

Washington, D.C. is chockablock with historians, but perhaps none so jaunty as satirist Christopher Buckley, who says that Congress in 1783 debated a "bill requiring air bags and rear brake lights on stagecoaches." Buckley, a Washington resident since 1981, has spent years making sport of politics; his first novel, The White House Mess (1986), gave us the feckless President Thomas N. Tucker, or TNT, who declared war on Bermuda, and Buckley's most recent, Supreme Courtship, published in 2008. Buckley makes his usual merry, but also shows a thoughtful fondness for what he calls this "Rome-on-the-Potomac landscape of gleaming white granite and marble buildings squatting on a vast green lawn." He bases his book on four walking tours, along the way tossing off facts (the spot where Francis Scott Key's son was fatally shot) and lore (a ghost is said to haunt the Old Executive Office Building). "Washington is a great city to walk around in," Buckley says. "For one thing, it's pretty flat. For another, something wonderfully historic happened every square foot of the way." In the excerpt that follows, Buckley covers the Washington of Abraham Lincoln:

On the 137th anniversary of the day Mr. Lincoln was shot, I joined a tour in Lafayette Square, on Pennsylvania Avenue across from the White House, conducted by Anthony Pitch, a spry man wearing a floppy hat and carrying a Mini-Vox loudspeaker. Pitch is a former British subject, and the author of a fine book, The Burning of Washington, about the British torching of the city on August 24, 1814. Pitch once saw, in the basement of the White House, the scorch marks left over from the incident. But for a thunderstorm that must have seemed heaven-sent, many of the city's public buildings might have burned to the ground. It's often said the presidential residence was first painted to cover up the charred exterior, but official White House historians say that isn't so, and point out that the building of pinkish sandstone was first whitewashed in 1798 and was known informally as the White House before the British ever set it aflame. Theodore Roosevelt made the name official in 1901 when he put "The White House" on the stationery.

But Pitch's theme today is Abraham Lincoln, and his enthusiasm for the man is little short of idolatrous. "He was one of the most amazing people who ever walked the earth,"says Pitch. "He was self-taught and never took umbrage at insults. That such a man was shot, in the back of the head, is one of the most monstrous insults that ever happened." I liked Pitch right away.

We crossed the street and peered through the White House fence at the North Portico. He pointed out the center window on the second floor. (You can see it on a twenty dollar bill.) On April 11, 1865, he told us, Abraham Lincoln appeared there and gave a speech. "It was the first time he had said in public that blacks should get the vote," Pitch explained. A 26-year-old actor named John Wilkes Booth was in the crowd outside, along with a man named Lewis Paine (born Powell). Booth had been stalking Lincoln for weeks. Booth growled, "That means nigger citizenship. That is the last speech he will ever make. . . . By God, I'll put him through."

Another man in the crowd that day was a 23-year-old physician, Charles Leale, who would be the first to care for the mortally wounded president. Pitch pointed out another window, three over to the right. "That room was called the Prince of Wales Room. That's where they did the autopsy and the embalming."

My mind went back 20 years, to when I was a speech writer for then Vice President George H.W. Bush, to a night I had dinner in that room, seated at a small table with President Reagan and two authentic royal princesses, both of them daughters of American actresses (Rita Hayworth and Grace Kelly). I mention this not to make you think, Well whupty do for you, Mr. Snooty. Let me emphasize: 99.98 percent of my dinners in those days took place at a Hamburger Hamlet or McDonald's or over my kitchen sink. But at one point in this heady meal, President Reagan turned to one of the princesses and remarked that his cavalier King Charles spaniel, Rex, would begin barking furiously whenever he came into this room. There was no explaining it, Reagan said. Then he told about Lincoln and suddenly the president of the United States and the two princesses began swapping ghost stories and I was left open mouthed and a voice seemed to whisper in my ear, I don't think we're in Kansas anymore, Toto.

For two years, I had a White House pass that allowed me everywhere except, of course, the second-floor residence. One time, hearing that Jimmy Cagney was about to get the Medal of Freedom in the East Room—where Abigail Adams hung out her wash to dry, Lincoln's body lay in state, and I once sat behind Dynasty star Joan Collins while she and husband number four (I think it was) necked as Andy Williams crooned "Moon River"—I rushed over from the Old Executive Office Building just in time to see President Reagan pin it on the man who had tap-danced "Yankee Doodle Dandy"and was now a crumpled, speechless figure in a wheelchair. I remember Reagan putting his hand on Cagney's shoulder and saying how generous he had been "many years ago to a young contract player on the Warner Brothers lot."

During the administration of George H. W. Bush, I was in the State Dining Room for a talk about Lincoln's time at the White House by professor David Herbert Donald, author of the much-praised biography Lincoln. I sat directly behind Colin Powell, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and remember that for an hour General Powell did not move as much as a centimeter. What I also remember of the evening was Professor Donald's stories about Mary Todd Lincoln's extravagances. Mrs. Lincoln was the Imelda Marcos of her day. This woman shopped. Among her purchases was the enormous rosewood bed that became known as the Lincoln Bed, even though her husband never spent a night in it. (The Lincoln Bedroom would become notorious during the Clinton years as a sort of motel for big donors to the Democratic Party.) At any rate, by 1864, Mary Todd Lincoln had run up a monumental bill. While field commanders were shouting"Charge!" Mrs. Lincoln had been saying "Charge it!"

Professor Donald ended his riveting talk by looking rather wistfully at the front door. He said that Mrs. Lincoln hadn't wanted to go to the theater that night. But the newspapers had advertised that Lincoln would attend the performance of Our American Cousin, and the president felt obliged to those who expected to see him there. In his wonderful book, April 1865, Jay Winik writes that Abe said he wanted to relax and "have a laugh." Never has a decision to go to the theater been so consequential.

"And so," said Professor Donald, "they left the White House together for the last time."

We're standing in Lafayette Square in front of a red brick building, 712 Jackson Place. The plaque notes that it's the President's Commission on White House Fellowships, the one-year government internship program. But in April 1865 it was the residence of a young Army major named Henry Rathbone, who was engaged to his stepsister Clara, daughter of a New York senator.

As Professor Donald recounts in his biography, April 14,1865, was Good Friday, not a big night to go out, traditionally. It's hard to imagine today, when an invitation from the president of the United States is tantamount to a subpoena, but the Lincolns had a hard time finding anyone to join them at the theater that night. His own secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, declined. (Mrs. Stanton couldn't stand Mrs. Lincoln.) General Grant also begged off. (Mrs. Grant couldn't stand Mrs. Lincoln.) Lincoln was subsequently turned down by a governor, another general, the Detroit postmaster(!), another governor (Idaho Territory) and the chief of the telegraph bureau at the War Department, an Army major named Thomas Eckert. Finally Abe turned to another Army major, Henry Rathbone, who said to the president, in so many words, OK, OK, whatever. The image of the president pleading with an Army major to sit in the president's box is the final tragicomic vignette we have of Lincoln. It's of a piece with his humanity and humility.

After Booth shot Lincoln, Rathbone lunged for Booth. Booth sank a viciously sharp seven-inch blade into his arm, opening a wound from elbow to shoulder. Rathbone survived, but the emotional wound went deeper. One day 18 years later, as U.S. Consul General in Hanover, Germany, he shot his wife dead. Rathbone himself died in 1911 in an asylum for the criminally insane. "He was one of the many people," Pitch said,"whose lives were broken that night."

I had last been to Ford's Theatre on my second date with the beautiful CIA officer who eventually, if unwisely, agreed to marry me. The play was a comedy, but even as I chuckled, I kept looking up at Lincoln's box. I don't know how any actor can manage to get through a play here. Talk about negative energy. And it didn't stop with the dreadful night of April 14,1865. Ford's later became a government office building, and one day in 1893, all three floors collapsed, killing 22 people.

You can walk up the narrow passageway to the box and see with your own eyes what Booth saw. It's an impressive leap he made after shooting Lincoln—almost 12 feet—but he caught the spur of his boot on the flags draped over the president's box and broke his leg when he hit the stage. Donald quotes a witness who described Booth's motion across the stage as "like the hopping of a bull frog."

In the basement of Ford's is a museum (due to reopen this spring after renovations) with artifacts such as Booth's .44 caliber single-shot Deringer pistol; a knife that curators believe is the one that Booth plunged into Rathbone's arm; the Brooks Brothers coat made for Lincoln's second inaugural, the left sleeve torn away by relic-hunters; the boots, size 14, Lincoln wore that night; and a small blood stained towel.

Members of a New York cavalry unit tracked down Booth 12 days later and shot him to death. Four of Booth's coconspirators,including Mary Surratt, proprietress of the boarding house where they plotted the assassination, were hanged on July 7. (The military tribunal that presided over their trial requested a lighter sentence for Surratt, but the request went unheeded.) Also displayed are the manacles the conspirators wore in prison awaiting their execution. Here, too, are replicas of the white canvas hoods they wore to prevent them from communicating with each other. Inevitably, one thinks of the Washington heat. Beneath a hood is a letter from Brevet Maj. Gen. John F. Hartranft, commandant of the military prison, dated June 6, 1865: "The prisoners are suffering very much from the padded hoods and I would respectfully request that they be removed from all the prisoners, except 195." That was Lewis Paine, who at about the same time Booth shot Lincoln attacked Secretary of State William Seward at his home on Lafayette Square, stabbing him in the throat and face. There's a photograph of Paine in manacles, staring coldly and remorselessly at the photographer. Perhaps it was this stare that persuaded Major General Hartranft that the hood was best left on.

We left Ford's Theatre and crossed the street to The House Where Lincoln Died, now run by the National Park Service. I had been here as a child, and remembered with a child's ghoulish but innocent fascination the blood-drenched pillow. It is gone now. I asked a ranger what happened to it. "It's been removed to a secure location," she said. Secure location? I thought of the final scene in the movie Raiders of the Lost Ark, as the ark is being wheeled away to be stored amid a zillion other boxes in a vast government warehouse. She added, "It was deteriorating." OK, I thought, but better not tell me where it is, I might steal it.

The air inside the house is close and musty. A little sign on a table says simply, "President Lincoln died in this room at 7:22 a.m. on April 15, 1865." Lincoln was 6-foot-4. They had to lay him down on the bed diagonally, with his knees slightly bent. He lived for nine hours.

I went back outside. Pitch was telling the story of Leale, the young Army surgeon. The first doctor to reach the Ford's theater box, Leale knew right away the wound was mortal. He removed the clot that had formed, to relieve pressure on the president's brain. Leale said the ride back to the White House would surely kill him, so Leale, two other physicians and several soldiers carried him across the street, to the house of William Petersen, a tailor. According to historian Shelby Foote, Mrs. Lincoln was escorted from the room after she shrieked when she saw Lincoln's face twitch and an injured eye bulge from its socket.

Secretary of War Stanton arrived and set up in the adjoining parlor and took statements from witnesses. A man named James Tanner, who was in the crowd outside, volunteered to take notes in shorthand. Tanner had lost both legs at the Second Battle of Manassas in 1862 but, wanting to go on contributing to the war effort, had taken up stenography. He worked through the night. Later he recalled: "In fifteen minutes I had enough down to hang John Wilkes Booth."

Mrs. Lincoln, having returned to the bedside, kept wailing, "Is he dead? Oh, is he dead?" She shrieked and fainted after the unconscious Lincoln released a loud exhalation when she was by his face. Stanton shouted, "Take that woman out and do not let her in again!"

Leale, who had seen many gunshot wounds, knew that a man sometimes regained consciousness just before dying. He held the president's hand. Lincoln never regained consciousness. When it was over, Stanton said, "Now he belongs to the ages."

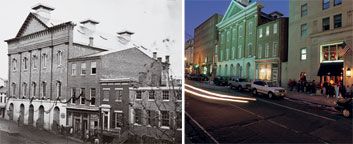

Mrs. Surratt's boardinghouse, where the conspirators hatched their plot, is not far away, near the corner of H and 6th Streets. It's now a Chinese-Japanese restaurant called Wok and Roll.

It's only a few blocks from The House Where Lincoln Died to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. There you'll find a plaster cast of Lincoln's hands made in 1860, after he won his party's nomination. A caption notes that "Lincoln's right hand was still swollen from shaking hands with congratulating supporters." Then there's one of the museum's "most treasured icons," Lincoln's top hat, worn to the theater the night he was assassinated. Here, too, is the blood stained sleeve cuff of Laura Keene, star of Our American Cousin, who, according to legend, cradled Lincoln's head after he was shot.

No tour of Lincoln's Washington would be complete without his memorial, on the Potomac River about a mile west of the museum. Finished in 1922, it was built over a filled-in swamp, in an area so desolate that it seemed an insult to put it there. In the early 1900s, the speaker of the House, "Uncle Joe" Cannon, harrumphed, "I'll never let a memorial to Abraham Lincoln be erected in that God damned swamp." There is something reassuring about thwarted congressional asseverations.

Lincoln's son, Robert Todd Lincoln, who had witnessed Lee's surrender to Grant at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, and was at his father's side when he died six days later, attended the memorial's dedication. Robert was then 78, distinguished looking in spectacles and white whiskers. You can see from a photograph of the occasion that he had his father's large, signature ears. (Robert, who had served as ambassador to Great Britain and was a successful businessman, died in 1926.)

Also present at the memorial's dedication was Dr. Robert Moton, president of the Tuskegee Institute, who delivered a commemorative speech but still was required to sit in the"Colored" section of the segregated audience. It's good to reflect that the wretched karma of this insult to the memory of Abraham Lincoln was finally exorcised 41 years later when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., stood on the memorial steps in front of 200,000 people and said, "I have a dream."

Inside the memorial, graven on the walls, are the two speeches in American history that surpass Dr. King's: the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural. I read the latter aloud to myself, quietly, so as not to alarm anyone. It clocks in at under five minutes, bringing the total of those two orations to about seven minutes. Edward Everett, who also spoke at Gettysburg, wrote Lincoln afterward to say, "I should flatter myself if I could come to the heart of the occasion in two hours in what you did in two minutes."

Daniel Chester French, who sculpted the statue of Lincoln that stares out on the Reflecting Pool, studied a cast of Lincoln's life mask. You can see a cast in the basement of the memorial, and it is hard to look upon the noble serenity of that plaster without being moved. Embarking from Springfield, Illinois, in 1861 to begin his first term as president, Lincoln said, "I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington." When I first read that speech as a schoolboy, I thought the line sounded immodest. Harder than what Washington faced? Come on! Only years later when I saw again the look on Lincoln's face that French had captured did I understand.

French knew Edward Miner Gallaudet, founder of Gallaudet University in Washington, the nation's first institution of higher learning for deaf people. Lincoln signed the bill that chartered the college. Look at the statue. Lincoln's left hand seems to spell out in American Sign Language the letter A, and his right hand, the letter L. Authorities on the sculptor say French intended no such thing. But even if it's just a legend, it's another way Lincoln speaks to us today.