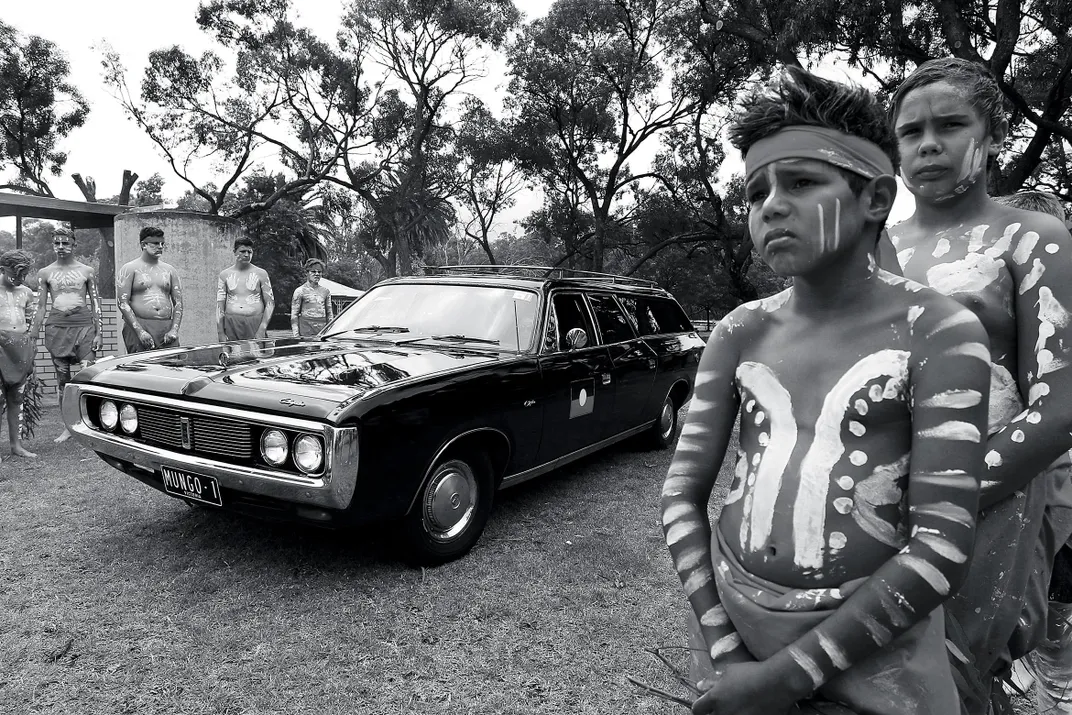

It was one of the more cinematic funeral caravans in recent memory. In November 2017, a black vintage hearse trundled across the verdant Australian sheep country west of Sydney toward the shimmering deserts of the outback. Laid out inside was a beautiful rough-hewn casket crafted from 8,000-year-old fossilized wood. A convoy of Aboriginal elders and activists followed close behind. At every stop on the way—in sonorously named bush towns like Wagga Wagga, Narrandera and Gundagai—the vehicle was met by jubilant crowds. In Hay, two Aboriginal men escorted the hearse into a park, where an honor guard of teenage boys carried the coffin to an ancient purification ceremony that involved cleansing it with smoking eucalyptus leaves. The rite was accompanied by traditional songs to didgeridoo music, dancing men in body paint and a slightly more contemporary Aussie “sausage sizzle.” After dark, a security guard stood vigil over the vehicle and its contents.

At last, on the third morning of the 500-mile trek, the hearse turned alone onto an unpaved desert highway toward the eerie shores of Lake Mungo, which despite its name has been a dry moonscape for the past 16,000 years. There, a crowd of several hundred people, including Australian government officials, archaeologists and representatives of Aboriginal groups from across the continent, fell into a reverent silence when they spotted the ghostly vehicle on the horizon kicking up orange dust.

The hearse was bearing the remains of an individual who died in this isolated spot over 40,000 years ago—one of the oldest Homo sapiens ever found outside Africa. His discovery in 1974 reshaped the saga of the Australian continent and our entire view of prehistoric world migration. The skeleton of Mungo Man, as he is known, was so well preserved that scientists could establish he was about 50 years of age, with his right elbow arthritic from throwing a spear all his life and his teeth worn, possibly from stripping reeds for twine.

Now he was returning home in a hearse whose license plate read, with typical Aussie humor, MUNGO1. He would be cared for by his descendants, the Ngiyampaa, Mutthi Mutthi and Paakantyi people, often referred to as the 3TTGs (Traditional Tribal Groups). “The elders had waited a long, long time for this to happen,” says Robert Kelly, an Aboriginal heritage officer who was present. Also standing in the crowd was a white-haired geologist named Jim Bowler, who had first found the skeleton in the shifting sands and had lobbied to have it returned to the Aboriginal people. Like many indigenous groups, the tribes believe that a person’s spirit is doomed to wander the earth endlessly if his remains are not laid to rest “in Country,” as the expression goes. Jason Kelly, a Mutthi Mutthi representative, was in the hearse on the last leg of the journey. “It felt like a wave was washing over me,” he recalls. “A really peaceful feeling, like everything was in slow motion.”

But even as the long-awaited, deeply symbolic scene was unfolding, scientists were making appeals to the Aboriginal elders not to bury the bones, arguing that the materials are part of a universal human patrimony and too important not to be studied further. In fact, from the moment he had been discovered, Mungo Man was entangled in bitter political battles over the “repatriation” of ancestral remains, a kind of dispute that would echo around the world, pitting researchers against indigenous peoples as diverse as Native Americans in Washington State, the Herero of Namibia, the Ainu of Japan and the Sámi of Norway, Finland and Sweden.

Bone collecting has been a key part of Western science since the Enlightenment, yet it’s now often assailed as unethical, and nowhere more so than in Australia. After generations of ignoring Aboriginal appeals, the country is now a world leader in returning human remains as a form of apology for its tragic colonial history. “The center of the debate is: Who owns the past?” says Dan Rosendahl, executive officer of the Willandra Lakes Region World Heritage Area. “Science says it belongs to everybody. People tried to lock onto that in Australia. But there were 1,700 generations before Europeans got here, so it’s clearly not everybody’s past.”

To better understand the growing chasm between the Western, scientific worldview and the spiritual outlook of indigenous cultures, I made my own expedition around the interior of Australia, meeting Aboriginal elders, museum curators and scientists key to the Mungo Man’s strange and fascinating saga. My final goal was the hallucinogenic landscape of Lake Mungo itself, which is gaining cult status among Aussie travelers as the Rift Valley of the Pacific Rim. At its core, Aboriginal people find the Western desire to place them within human history irrelevant. Scientists trace human origins to Africa 2.5 million years ago, when the genus Homo first evolved. The species Homo sapiens emerged in East Africa 200,000 years ago, and began to migrate from the continent around 60,000 years ago. (Other species had likely first migrated two million years ago; Neanderthals evolved 400,000 years ago.) The Aboriginal people believe that they have lived in Australia since it was sung into existence during the Dreamtime. The carbon dating of Mungo Man came as no surprise to them. “To us blackfellas, we’ve been here forever,” said Daryl Pappin, a Mutthi Mutthi archaeological fieldworker. “That date, 42,000 years, was published as a ‘discovery.’ That’s not true. They’ve just put a timeline on it that whitefellas can accept.”

* * *

My sojourn began in Australia’s capital, Canberra—Down Under’s version of Brasília—an artificial city created as a gateway to the continent’s vast hinterland. Today, its broad, empty highways are lined with Art Deco monuments and avant-garde structures scattered like giant Lego blocks. By its serene lake, I met Michael Pickering, director of the Repatriation Program at the National Museum of Australia, which oversaw Mungo Man’s hand-over. “Other indigenous communities were watching worldwide,” Pickering, a soft-spoken character in his early 60s who travels the world dealing with human remains, said proudly as we climbed into his SUV. Most skeletons in museums are only 500 years old and in poor condition, he said, especially if they were found in damp coastal areas, so their return arouses little scientific opposition. But Mungo Man was intact, a unique piece of prehistoric evidence.

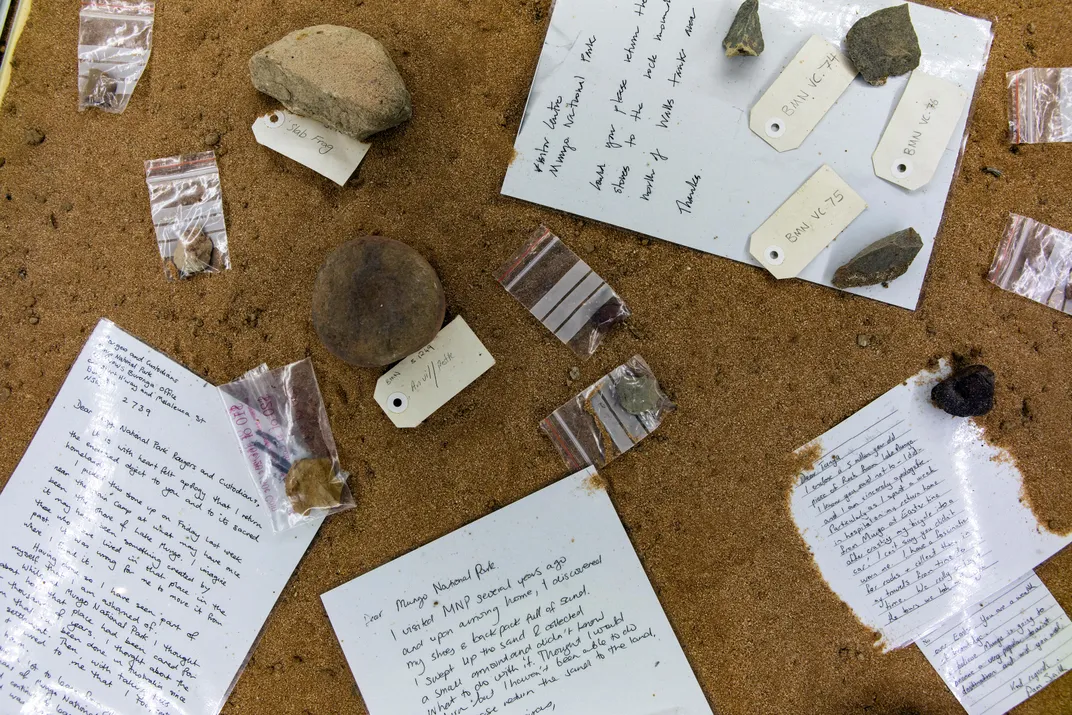

We drove from the picturesque lakefront to a prosaic, ramshackle suburb called Mitchell. In a neighborhood with warehouses selling industrial appliances in the shade of stringy eucalyptuses, Pickering stopped at a security gate and punched in a code to open it; only after more codes, special keys and signing a logbook could we enter a cavernous museum storage facility crowded with relics, like a theater prop room. In archival drawers were convict leg irons from the early 1800s, jars of antique marsupial specimens, copperplate etchings of native plants made by naturalists on Capt. James Cook’s 1770 expedition. Our goal was a room within the warehouse—the Repatriation Unit. “It’s not pretty, but very functional,” Pickering said, as he unlocked the door. The space is austere and solemn, with beige walls and icy climate control. Neatly stacked in a back room were some 300 cardboard boxes, some as small as shoe boxes, each one containing Aboriginal bones. Many were retrieved from Canberra’s now-defunct Institute of Anatomy, which exhibited skeletons to the public from the 1930s to 1984. Some have been sent by private Australians, sometimes in cookie tins or crates. Others came from museums in the United States, Britain and Europe, all of which have held Aboriginal skeletons for study or display.

“We had 3,000 individuals, all indigenous, in the ’80s,” Pickering marveled. “Rooms full of bones.” Locating the Aboriginal communities to return them to involved serious detective work. Many of the skeletons were mixed up, their labels faded or eaten by silverfish, and their origins were only traced through century-old correspondence and fading ledgers.

The unit’s centerpiece is a table where skeletons are laid out for tribal elders, who wrap the remains in kangaroo skin or wafer-thin paperbark to take back to Country. But not all of them want to handle the remains, Pickering said, often asking staff to do it instead. “It can be a harrowing experience for the elders,” says heritage officer Robert Kelly, who has worked in repatriation since 2003. “To see the skulls of their ancestors with serial numbers written on them, holes drilled for DNA tests, wires that were used for display mounts. They break down. They start crying when they see these things.”

Although Mungo Man had never been displayed or seriously damaged by intrusive scientific tests, emotions ran high in the lab on the morning of November 14, 2017, when his bones were carefully placed in the casket here for his funeral procession to the west. The first ceremony was held, of all places, in the storage facility’s parking lot, near the vintage hearse, its doors marked with the red, black and yellow of the Aboriginal flag. Warren Clark, an elder from the Paakantyi tribal group, surveyed the bare asphalt expanse during his speech. “This is not home for me, it’s not home for our ancestors, either,” he said, “and I’m sure their spirits won’t rest until they are buried back on our land. Our people have had enough. It’s time for them to go home.”

* * *

Lake Mungo’s remoteness is central to its appeal to travelers. “Only people who are really interested will get there,” said Rosendahl of the World Heritage office. He wasn’t exaggerating: The journey still qualifies as an outback adventure. My jumping-off point was the isolated mining outpost of Broken Hill, which I reached in a small propeller plane packed with engineers. At first, the town felt like a time warp. An enormous slag heap looms as a reminder of its heyday in the early 1900s as the world’s largest producer of lead, zinc and silver. Monstrous trucks carrying livestock rumble down the main street. Buildings—old butcher shops, trade union clubs, barbers—sport Wild West-style verandas with ornate iron lace. But the retro illusion was punctured as soon as I checked into the Palace Hotel, a Victorian pub that was taken over in the 1970s by an Italian immigrant who fancied himself a painter and used every interior surface as a canvas, including the ceilings. The hotel pub was a set for the 1994 film The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, about a trio of drag queens touring the outback. Ever since, it has been a pilgrimage site for gay men, hosting weekly transvestite shows. Today, the crusty mineworkers in flannel shirts and broad-rimmed hats nursing their beers at the bar nod amiably to the technicolor blur of buffed men streaming by in sparkly sequins, wigs and feathers.

My guide was a U.S.-raised artist named Clark Barrett, who moved to Broken Hill 40 years ago so he could fall off the map. “I wanted to live somewhere I could see the rotation of the earth,” he explained as we hit the road in a 4x4. He still camps in the desert for weeks at a time, painting and observing the sky and stars. (“The rotation of the earth makes my day” is his favorite joke.) Outside Broken Hill, the unpaved highway sliced without a single curve across the lonely, existential landscape, which was given a degree of notoriety by another Aussie movie, Mad Max 2. Mile after mile of flat scrub was interrupted only by the occasional tree rising like a stark sculpture, a mailbox fashioned out of an eight-gallon drum, or a silent township with little more than a gas station. We were closely monitoring the weather. Rain had fallen the night before and threatened to turn the road into a slippery morass.

This was mythic Australia, and far from lifeless. “Mobs” of kangaroos bounded by, along with strutting emus. Shingleback lizards, with shiny black scales resembling medieval armor and garish blue tongues, waddled onto the road. The native bird life was raucous, brilliant colored and poetically named—lousy jacks, mulga parrots, rosellas, willy wagtails and lorikeets.

By the time we reached the turnoff to Mungo National Park, the bars on our cellphones were down to zero. We screeched to a halt before the only accommodation, a desert lodge with lonely cabins arranged in a circle. The only sound was the wind moaning through the pine trees. At night, beneath the brilliant swath of the Milky Way, total silence fell. The sense of entering another era was palpable—and mildly unnerving.

* * *

When Mungo Man walked this landscape some 40,000 years ago, the freshwater lake was around 25 feet deep, teeming with wildlife and surrounded by forests dappled with golden wattle. Like the rest of Australia, it had once been the domain of megafauna, a bizarre antipodean menagerie that had evolved over the 800 million years of isolation before the Aboriginal hunter-gatherers arrived. There were enormous hairy wombats called Diprotodons that weighed over two tons, towering flightless birds called Genyornis, and Macropus titan, a nine-foot-tall kangaroo. The megafauna’s fate was sealed when Homo sapiens landed on the Australian coast sometime between 47,000 and 65,000 years ago. Scientists believe that around 1,000 sapiens traveled by boat from Indonesia—just 60 miles away then, thanks to low ocean levels—to become the first human inhabitants of Australia. Scholars now regard the sea voyage as a major event in human history: It was “at least as important as Columbus’ journey to America or the Apollo 11 expedition to the moon,” according to historian Yuval Noah Harari in Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. The latest scientific theories suggest the megafauna were hunted to extinction by the newcomers and had disappeared by the time of Mungo Man. But the landscape was still bountiful, an Aussie Garden of Eden: Middens reveal that residents harvested fish, mussels and yabbies (freshwater crayfish) from the lake waters, and trapped small marsupials, collected emu eggs and grew sweet potato.

The following millennia saw climate change on an epic scale. The last ice age began 30,000 years ago; by the time it had ended, 18,000 years ago, the melting ice caps had made Australian coastal water levels rise 300 feet, creating its modern outline. The interior lakes around Willandra (there are actually 19 of them) dried out and emptied; along each one’s eastern flank, the relentless outback winds created the crescent-shaped mountain of sand called a “lunette.” Arid though the landscape was, the nomadic Aboriginal groups, the 3TTGs, knew how to live off the desert and continued to use it as a regular meeting place.

But the speed of change accelerated exponentially after the first British settlement was founded in Sydney in 1788. It was a cataclysm for Australia’s first inhabitants. Within a few short decades, British explorers were arriving in the Willandra area, followed by streams of white settlers. In the 1870s, colonial police forcibly moved Aboriginal people off the land into reserves and religious missions, and farmers carved out stations (ranches). Aboriginal culture was dismissed as primitive; the few British scientists who considered the Aboriginal people believed they had landed relatively recently. Some 50,000 sheep were sheared annually at the station named after St. Mungo by its Scottish founders, and their hoofs stripped the top soil from the dry lake floor. Imported goats devoured native trees; imported rabbits riddled the earth with their burrows; and vulnerable marsupials like the pig-footed bandicoot and the hairy-nosed wombat vanished. The sand kicked up by the sheep began to scarify one lunette, stripping the native vegetation that bound it together. The sand arc was a scenic oddity dubbed the Walls of China, possibly by Chinese laborers.

As late as the 1960s, the region was still so little known to white Australians that the lakes had no names. It was simply left off maps until a geomorphology professor flew from Broken Hill to Melbourne in 1967 and looked out the window. He saw the pale shapes in the desert below and recognized them as fossilized lake beds. Back at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, he suggested to a middle-aged student, a soulful geologist working on ancient climate change in Australia, Jim Bowler, to investigate. Bowler had no idea that the visit would transform his life.

* * *

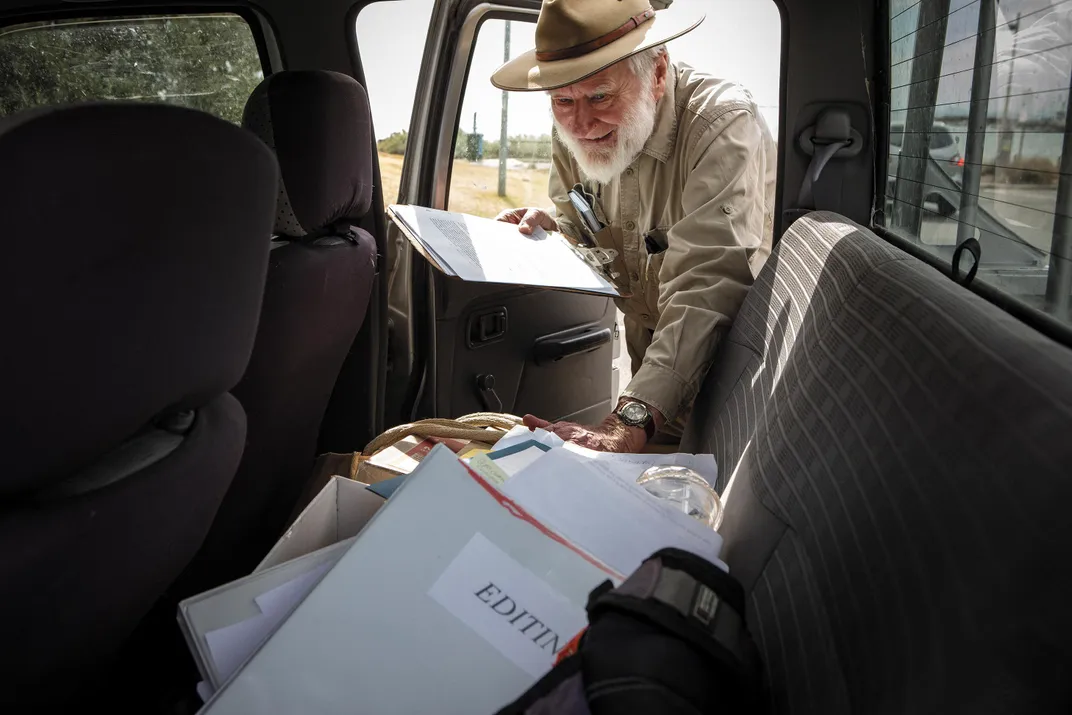

Now 88 and a legend in Australia, Bowler lives in Brighton, a tidy seaside suburb of Melbourne, a city of Victorian monuments once considered the most stolidly “British” in the Antipodes. When I poked my head into Bowler’s bungalow, his wife, Joan, was surprised I hadn’t seen him sitting across the road inside his pickup truck, where he likes to work. “He’s a bit strange,” she said, shaking her head as she led me up the driveway. “But I suppose all academics are.”

Bowler was indeed sitting in the front seat of a silver Nissan, tapping away on his laptop and surrounded by a chaos of notes, pens and electrical cords. “This is the only place I can get a little peace,” he laughed. Although he has long been a university professor, his lanky frame and sun-beaten skin were reminders of his youth farming potatoes and mustering cattle in the Snowy Mountains, as well as his decades working as a field geologist in some of Australia’s harshest corners. He was dressed as if he were about to head out on safari any minute, with a khaki Bushman’s vest and an Akubra hat by his side, although his white chin beard gave him the air of an Edwardian theologian. (He studied for a time to be a Jesuit priest.) Bowler suggested I clear some space and hop into the passenger seat so that we could drive around the corner to Port Phillip Bay. There, sitting in the car and gazing at seagulls over the beach, he conjured the outback.

Bowler first went to Lake Mungo in 1968 to map ice age geology. “I could see the impact of climatic change on the landscape,” he explained. “The basins were like gauges. But if you follow water, you follow the story of human beings. Inevitably, I found myself walking in the footsteps of ancient people.” Bowler realized that the exposed strata of the lunettes created an X-ray of the landscape over the last 100 millennia. He spent weeks exploring on a motorbike, naming the lakes and the major geological layers after sheep stations: Gol Gol, Zanci, Mungo. “All sorts of things were popping out of the ground that I had not expected to see,” he recalled. “I would find shells and stone flakes that looked transported by humans.” The strata placed them at well over 20,000 years old, but archaeologists wouldn’t believe him: The conventional wisdom was the Aboriginal people arrived in faraway northern Australia 20,000 years ago at the earliest.

His first discovery—a skeleton that would be dubbed “Mungo Lady”—was, in retrospect, a haphazard affair. On July 15, 1968, Bowler spotted charcoal and bone fragments by Mungo’s shoreline, but the news was greeted with indifference back at ANU. It took eight months before he and two colleagues wangled a research grant—$94 to cover fuel for a VW Kombi bus and two nights in a motel. When the trio cleared away the sand, “out dropped a piece of cranium,” Bowler recalls. Then came part of a jawbone, followed by a human tooth. The body had been burned, the bones crushed and returned to the fire.

After they carried the bones back to Canberra in a suitcase, one of the party, an ANU physical anthropologist named Alan Thorne, spent six months reconstructing the skull from 500 fragments. The result proved beyond doubt that this was Homo sapiens—a slender female, around 25 years old. The discovery coincided with the pioneering days of “new archaeology,” using scientific techniques such as carbon dating (which measures carbon-14, a radioactive isotope of organic matter) to place artifacts in specific time frames. When Mungo Lady was dated at 26,000 years, it destroyed the lingering 19th-century racist notion, suggested by misguided followers of Charles Darwin, that Aboriginal people had evolved from a primitive Neanderthal-like species.

Epilogue for the Ancestors

Smithsonian researchers forge a new policy for returning human remains to indigineous people overseas —Emily Toomey

Today the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) cares for collections made by the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land of 1948. A collaboration among Australian institutions, the Smithsonian and National Geographic, the ten-month venture yielded thousands of biological specimens and cultural items, which are still being studied today. The Aboriginal bark paintings commissioned by the researchers sparked global awareness of this art form. For decades the remains of over 40 Aboriginal individuals were kept at NMNH. By 2010, the museum, working with officials and indigenous groups in Australia, had returned the Arnhem Land remains on loan from the Australian government, and the museum is working closely with Aboriginal groups to repatriate remains collected from other places in Australia. Returning the Arnhem Land remains to Australia, says Joshua A. Bell, curator of globalization, “helped us establish more formal guidelines for engaging in international repatriation.”

But it was Bowler’s discovery of Mungo Man five years later that made world headlines. On February 26, 1974, by now doing his PhD, he was again at Lake Mungo when unusually torrential summer rains hit. “There was a pristine new surface on the dunes,” he recalls. He went back to where he had found Mungo Lady and followed the same geological “horizon.” He spotted white bone. “I brushed away the sand and there was a mandible, which meant the rest of the body might be in the ground.” He rushed to find a telephone in the nearby homestead. “Happily, it worked! We were 100 miles from any other building.”

This time, ANU archaeologists hurried to the scene. They only had to smooth the sand away to find an intact male skeleton. He had been ceremoniously buried; his hands were folded over the pelvis and traces of red ocher enveloped him from cranium to loin. The ocher had been carried a great distance—the nearest source was over 130 miles away—and had been either painted onto the body or sprinkled over the grave. “We suddenly realized this was a ritual site of extraordinary significance,” Bowler recalled. “It was a shock. You’re sitting in the sand and suddenly realize that something beyond you has happened.” The next surprise came when carbon dating put “Mungo Man” at 40,000 to 42,000 years old—some 5,000 years older than the Cro-Magnon sites in Western Europe. The researchers retested Mungo Lady; the new data showed that she had lived around the same time as Mungo Man.

The news revolutionized the timeline of human migration, proving that Homo sapiens had arrived in Australia far earlier than scientists imagined as part of the great migration from East Africa across Asia and into the Americas. Post-Mungo, the most conservative starting date is that our species left Africa to cross the Asian landmass 70,000 years ago, and reached Australia 47,000 years ago. (Others suggest the Aboriginal arrival in Australia was 60,000 years ago, which pushes the starting date of migration back even further.)

Just as revolutionary was what Mungo Man meant for the understanding of Aboriginal culture. “Up until Mungo, Aboriginals had been frequently denigrated,” Bowler said bluntly. “They were ignorant savages, treacherous. Suddenly here was a new indication of extraordinary sophistication.” The reverent treatment of the body—the oldest ritual burial site ever found—revealed a concern for the afterlife eons before the Egyptian pyramids. Two of Mungo Man’s canine teeth, in the lower jaw, were also missing, possibly the result of an adolescent initiation ceremony, and there were the remains of a circular fireplace found nearby. “It took me a long time to digest the implications,” Bowler said. Today, Aboriginal people still use smoke to cleanse the dead. “It’s the same ritual, and there it was 40,000 years ago.” All the evidence pointed to a spectacular conclusion: Aboriginal people belong to the oldest continuous culture on the planet.

* * *

News of Mungo Man’s discovery, presented as a triumph by scientists, provoked outrage in the Aboriginal communities; they were furious that they had not been consulted about their ancestor’s removal from his homeland. “I read about it in the newspaper like everybody else,” recalls Mary Pappin, a Mutthi Mutthi elder. “We were really upset.” The first quiet protests over archaeological work had begun years earlier over Mungo Lady, led by her mother, Alice Kelly, who would turn up with other women at new digs and demand an explanation, carrying a dictionary so she could understand the jargon. “My mum wrote letters,” recalls her daughter. “So many letters!” Removing Mungo Man seemed the height of scientific arrogance. Tensions reached such a point by the end of the 1970s that the 3TTs placed an embargo on excavation at Lake Mungo.

Mungo Man surfaced precisely at a time when Australia was wrestling with a crisis in race relations that dates back to the colonial era. The first British settlers had mistakenly dismissed the Aboriginal people as rootless nomads, ignoring their deep spiritual connection to the land based on the mythology of the Dreamtime. An undeclared frontier war followed, involving massacres and enforced removals. Whites “harvested” Aboriginal skeletons, often by pillaging grave sites or even after bloodbaths, for study and display in museums in Britain, Europe and the States, in some cases to “prove” that indigenous races were lower on the evolutionary scale than Anglo-Saxons. The macabre trade continued in Australia until the 1940s (as it did for Native American remains in the U.S.); the last official expedition, a joint Australian-U.S. effort involving the Smithsonian Institution and others that would become controversial, occurred in 1948. Aboriginal people felt each removal as a visceral affront.

This bleak situation began to change in the 1960s when, influenced by the civil rights movement and Native American campaigns in the States, Aboriginal activists demanded that they be given citizenship, the vote and, by the 1970s, ownership of their traditional homelands. The standoff between the 3TTGs and scientists began to thaw in 1992, when ANU agreed to return Mungo Lady to the traditional owners. Relations improved as young Aboriginal people were trained as rangers, archaeologists and heritage officials, and in 2007, the 3TTGs gained joint management of the parks. But an impasse remained over the fate of Mungo Man.

It was support from Jim Bowler that tipped the balance. In 2014, he wrote in a widely publicized editorial that he felt a responsibity to help Mungo Man go home. “I was clobbered!” he laughs now. “They said, ‘Bowler’s gone off tilting at windmills! He’s out there like Don Quixote.’” Scientists argued that the skeleton should be kept safe, since future developments in DNA research and improved X-ray tests might one day reveal new insights about the diet, life expectancy, health and cultural practices of early humans, or about mankind’s origins. (Did Homo sapiens evolve from a single “African Eve” or develop in separate locations? Did our species overwhelm the other known human species such as Homo neanderthalensis and Homo erectus, or interbreed with them?)

The process of returning Aboriginal remains sped up in 2002, when the Australian government recommended that repatriations be “unconditional.” Unlike in the U.S., where federal laws govern the return of Native American remains, the directive had no legal force; nevertheless, Australian institutions responded with arguably more energy. A network of heritage officers began systematically connecting with Aboriginal communities all over Australia to empty museum collections. “We try to be proactive,” says Phil Gordon, project manager for repatriation at Sydney’s Australian Museum. “People also do contact us. They call you up on the phone: ‘Hey! You got any of my ancestors?’”

Mungo Man’s return was the climax of this anti-colonial shift. “It’s about righting the wrongs of the past,” says Aboriginal heritage officer Kelly, who wrote the formal letter asking for Mungo Man’s return. Michael Pickering in Canberra was one of many older white Australian museum workers who have seen a complete reversal of attitudes in their lifetimes. “If you’d asked me at age 22,” he admitted, “I would have said it was a crime against science. But now I’m older and wiser. Science is not a bad thing. But society benefits from other forms of knowledge as well. We learn so much more from repatriation than letting bones gather dust in storage.”

All these emotions came together in November 2017 as the hand-carved casket was laid out at Lake Mungo and covered with leaves. As the smoking ceremony began, recalls Jason Kelly, a willy willy (dust devil) swept from the desert and across the casket. “It was the spirit of Mungo Man coming home,” he said. “It felt like a beginning, not an end. It was the beginning of the healing, not just for us, but for Australia.”

* * *

Today, Mungo Man, whose bones were returned to the Aboriginals, lies in an interim “secret location” awaiting reburial, which will probably occur sometime next year. When I went to the park visitor’s center, a ranger pointed to a door marked “Staff Entrance Only.” “He’s down the back,” he confided. “But don’t worry, mate, he’s safe. He’s in a bank vault.” When he started showing visitors on a map the spot where the bones were found by Jim Bowler, the ranger next to him rolled his eyes and muttered, “You’re not supposed to tell people that!”

The human presence may have elements of an Aussie sitcom, but the landscape is among the eeriest in the outback. At dusk, I climbed the Walls of China, crossing the rippling Sahara-like dunes and skirting the ribs of a wombat and shards of calcified tree trunk among the craggy spires. Although only 130 feet high, the dunes tower over the flat desert. Peering to the south, where Mungo Man and Mungo Lady had both emerged from the sand, I tried to grasp what 42,000 years actually meant. The Roman Empire ended roughly 1,500 years ago, Troy fell 3,200 years ago, the Epic of Gilgamesh was written around 4,000 years ago. Beyond that, time unraveled.

I finally made the mental leap into prehistory when I found myself on a hunt with an ice age family. In 2003, a young Aboriginal ranger, Mary Pappin Jr. (granddaughter of the activist Alice Kelly), made an astounding discovery near Lake Mungo: more than 560 footprints, later shown to be around 21,000 years old. This miraculous snapshot of Pleistocene life featured 12 men, four women and seven children who had walked across the soft clay around the lake, which dried like concrete in the sun. The foot impressions were then immersed in drifting sands and preserved.

The footprints look as if they were made yesterday. Analysis by expert trackers reveals that the group, presumably an extended family, was moving at the steady pace of long-distance runners. The men were mostly on the outside of the group, perhaps in hunting formation; at one point, they paused and rested their spears. The tallest male, the forensic analysis suggests, was 6-foot-6 with size 12 feet. It seems that one man had lost a leg and hopped without the aid of a crutch. Another of the adults was walking at a slower pace with children—one wonders what they were talking about. Suddenly the millennia evaporated.

* * *

If even a casual visitor can have cosmic flashes in this otherworldly setting, Jim Bowler has come to feel he was guided by a higher force to Lake Mungo. “The unlikely probability of being there just when Mungo Man’s skeleton was starting to appear—and find things thoroughly intact!” he laughs. “It’s one in a million.” As he approaches 90, he is racing to complete a book that will connect his personal narrative to larger issues. “Mary Pappin told me: ‘Mungo Man and Mungo Lady, you didn’t find them. They found you!’” he says. They had messages to deliver, such as telling white Australians that the time has come to acknowledge the injustices inflicted upon Aboriginal people.

Bowler, the doctor of geology and the lapsed Jesuit, also wants Western culture to appreciate the indigenous worldview: “Do we have something to learn from Aboriginal people?” he asks. “And if so, what?” On sleepless nights he asks for guidance from Mungo Man himself. “Aboriginal people have a deep spiritual connection to the land. The ocher Mungo Man was buried in was a link to the cosmos. Western culture has lost these connections.” The use of stories and myths by Aboriginal people, Native Americans and other indigenous groups also satisfies deep human longing for meaning. “Science has trouble explaining mysteries. There’s an entire reality beyond the scientific one.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/e7/e0e73c85-2df2-45a5-844f-c86ffbb3a65d/sep2019_a04_mungoman.jpg)