Murder in Tibet’s High Places

The Dalai Lama is one of the world’s most revered religious leaders, but that didn’t prevent four holders of the office from mysteriously dying

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120410105038Potala-palace-thumb.jpg)

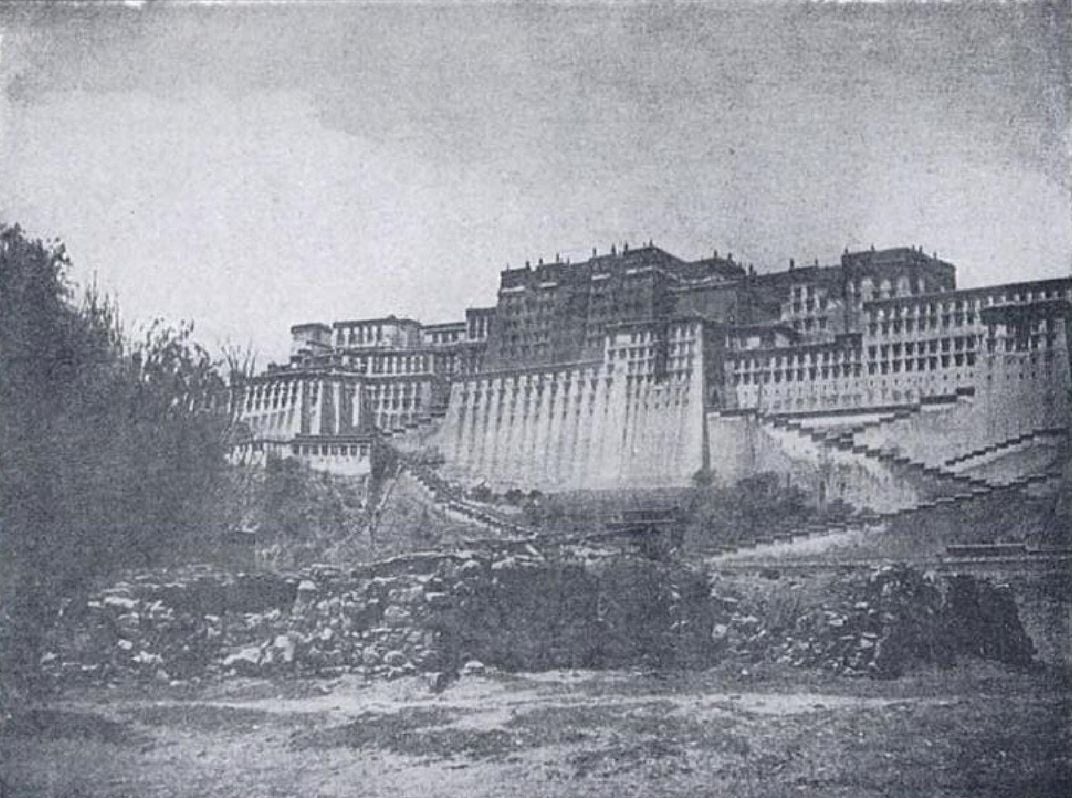

Few buildings inspire awe in quite the way that the Potala Palace does. Set high on the great Tibetan plateau, against the looming backdrop of the Himalayas, the vast structure rises 400 feet from a mountain in the middle of Lhasa, taking the uppermost apartments on its thirteenth floor to 12,500 feet above sea level. The palace is at once architecturally striking and historically significant. Until the Chinese occupation of 1951, it was also the winter home of the 14th Dalai Lama, believed to be the reincarnation of a long line of religious leaders dating back to the late fourteenth century.

For Buddhists, the Potala is a holy spot, but even for visitors to the Tibetan capital it is hardly the sort of place one would expect to find steeped in intrigue and corruption. Yet during the first half of the 19th century, the palace was the scene of a grim battle for political supremacy fought among monks, Tibetan nobles and Chinese governors. Most historians of the country, and many Tibetans, believe that the most prominent victims of this struggle were four successive Dalai Lamas, the ninth through the twelfth, all of whom died in unusual circumstances, and not one of whom lived past the age of 21.

The early 1800s are a poorly documented period in Tibet’s history. What can be said is that these dark days began with the death of the eighth Dalai Lama in 1804. Jamphel Gyatso had been enthroned in 1762 and, like three out of four of his immediate predecessors, lived a long life by the standards of the time, bringing a measure of stability to his country. But, by the time of his death, the augeries for Tibet’s future were not propitious. Qianlong, the last great ruler of China’s Qing dynasty, had abdicated in 1796, leaving his empire to successors who took less interest in a region that China had dominated for half a century. The decline of the Qing had two consequences: the governors—ambans—sent from Beijing in pairs to rule in Lhasa discovered that they had a free hand to meddle as they wished; and the Tibetan nobility, which had alternately collaborated with the Qing and resented them, sensed an opportunity to recover the influence and power they had lost since 1750. For the Chinese, the power vacuum that existed during a Dalai Lama’s minority made governing their distant dependency easier; conversely, any Buddhist leader with a mind of his own was a threat. For Tibet’s nobility, a Dalai Lama who listened to the ambans was most likely an imposter who fully deserved a violent end.

Add to that toxic stew a series of infant Dalai Lamas placed in the care of ambitious regents drawn from a group of fractious rival monasteries, and it’s easy to see that plenty of people might prefer it if no self-willed, adult and widely revered lama emerged from the Potala to take a firm grip on the country. Indeed, the chief difficulty in interpreting the murderous politics of the period is that the story reads too much like an Agatha Christie novel. Every contemporary account is self-serving, and everybody gathered in the Potala’s precincts had his own motive for wanting the Dalai Lama dead.

The palace itself made an evocative setting for a murder mystery. To begin with, it was ancient; construction on the site had begun as early as 647, in the days of Tibet’s greatest early ruler, Songtsän Gampo, and just as the medieval Tibetan Empire began to emerge as a genuine rival to Tang dynasty China. The structure that we know today mostly dates to a thousand years later, but the Potala belongs to no one period, and the complex was still being expanded in the 1930s. It’s really two palaces: the White, which was the seat of government until 1950, and the Red, which houses the stupas—tombs—of eight Dalai Lamas. Between them, the two buildings contain a thousand rooms, 200,000 statues and endless labyrinthine corridors, enough to conceal whole armies of assassins.

Only a few of the Potala’s many chambers, the first Westerners to gain access to the complex learned, were decorated, properly lit or ever cleaned. Perceval Landon, a correspondent of the London Times who came to Lhasa in 1904 with the British invasion force led by Francis Younghusband, and saw the Potala as it must have been a century earlier, was bitterly disappointed by its interiors—which, he wrote, were illuminated solely by smoldering yak butter and were

indistinguishable from the interiors of a score of other large Tibetan lamaseries…. Here and there in a chapel burns a grimy butter lamp before a tarnished and dirty image. Here and there the passage widens as a flight of stairs breaks the monotony of grimy walls. The sleeping cells of the monks are cold, bare and dirty…. It must be confessed, though the words are written with considerable reluctance, that cheap and tawdry are the only possible adjectives that can be applied to the interior decoration of this great palace temple.

The Dutch writer Ardy Verhaegen sketches in more of the background. The eighth Dalai Lama, he points out, although long-lived (1758-1804), never displayed much interest in temporal affairs, and long before the end of his reign political power in Tibet was being wielded by regents drawn from the ranks of other high lamas in monasteries around the capital. By the 1770s, Verhaegen writes, these men “had acquired a taste for office and were to misuse their powers to further their own interests.” The situation was made worse by the death in 1780 of Lobsang Palden Yeshe, the influential Panchen Lama who had stood second in the hierarchy of Yellow Hat Buddhism, and by virtue of his office played a key role in identifying new incarnations of the Dalai Lama. His successors—only two during the whole of the next century—were much less forceful characters who did little to challenge the authority of the ambans.

According to Verhaegen, several suspicious circumstances link the deaths of the eighth Dalai Lama’s four successors. One was that the deaths began shortly after Qianglong announced a series of reforms. His Twenty-Nine Article Imperial Ordinance introduced an unwelcome innovation into the selection of a new Dalai Lama. Traditionally, that process had involved a combination of watching for signs and wonders, and a test in which an infant candidate was watched to see which of various personal items, some of which had belonged to earlier incarnations, were preferred; the novelty Qianlong introduced was the so-called Golden Urn, from which lots were to be drawn to select a candidate. The Urn’s real purpose was to allow China to control the selection process, but in the case of the ninth and tenth Dalai Lamas, the wily Tibetans found ways of circumventing the lottery, to the considerable displeasure of Beijing. One possibility is that the Chinese arranged the deaths of these two incarnations in order to have the opportunity to impose a Dalai Lama they approved of.

The second circumstance that Verhaegen calls attention to is that all four of the Lamas who died young had made the sacred journey to Lhamoi Latso lake shortly before their passing. This visit, made “to secure a vision of his future and to propitiate the goddess Mogosomora,” took the Lama away from Lhasa and exposed him to strangers who might have taken the opportunity to poison him. Not that the Potala was safe; alternately, Verhaegen suggests,

it is also possible they were poisoned by cooks… or by the regents when given a specially prepared pill, meant to increase vitality.

Whatever the truth, the first in what would become a series of suspiciously premature deaths took place in 1815 when the ninth Dalai Lama, nine-year-old Lungtok Gyatso, fell dangerously ill with what was said to be pneumonia contracted while attending a festival deep in the Tibetan winter. According to Thomas Manning, the first British visitor to Tibet, who met him twice in Lhasa, Lungtok had been a remarkable boy: “beautiful, elegant, refined, intelligent, and entirely self-possessed, even at the age of six.” His death came during the regency of Dde-mo Blo-bzan-t’ub-btsan-’jigs-med-rgya-mts’o, abbot of bsTan-rgyas-glin. Derek Maher notes that Demo (as he is, thankfully, known outside the austere halls of Tibetan scholarship) “suffered from episodes of mental illness.” Beyond that, however, the only certainties are that Lungtok died at the Potala, that his illness followed a visit to Lhamoi Latso Lake—and that a number of death threats were made against him just before he died. Rumors circulating in Lhasa, the historian Günther Schulemann says, suggested that “certain people trying to get rid of” the boy.

The ninth’s successor, Tsultrim Gyatso, lived a little longer; he was nearly 21 years old when he suddenly fell ill in 1837. Tsultrim—who displayed some unusual traits, including a predisposition for the company of commoners and a love of sunbathing with his office clerks—had just announced plans for an overhaul of the Tibetan economy and an increase in taxation when he entirely lost his appetite and grew dangerously short of breath. According to official accounts, medicines were administered and religious intervention sought, but his decline continued and he died.

There would have been no solid reason to doubt this version of the tenth Dalai Lama’s death had not one Chinese source stated unequivocally that it was caused not by disease but by the unexplained collapse of one of the Potala’s ceilings on him while he was asleep. Basing his account on a set of documents addressed to the Chinese emperor 40 years later, W.W. Rockhill, the dean of American scholars of Tibet, records that, once the dust and rubble had been cleared, a large wound was discovered on the young man’s neck.

It is far from clear whether this mysterious wound was inflicted by an assailant or a piece of falling masonry, but historians of the period are in full agreement as to who had the best motive for wanting the tenth Dalai Lama dead: the regent Nag-dban-’jam-dpal-ts’ul-k’rims, known as Ngawang to most Western writers. He was himself a reincarnated lama who had held power since 1822; the Italian scholar Luciano Petech damningly describes him as glib, full of guile and “by far the most forceful character in 19th century Tibet.” Ngawang was the subject of an official Chinese inquiry, which, in 1844, stripped him of his estates and ordered his banishment to Manchuria; Verhaegen writes that he planned “to extend his authority during the minority of the next Dalai Lama” and was generally thought in Lhasa to have hastened his ward’s death, while Schulemann notes the rather circumstantial detail that the regent “did not seem overly sad at the news and said very little about it.” Yet, as Petech points out, the evidence is far from sufficient to secure the conviction of Ngawang in a court of law. The Chinese investigation focused on broader allegations of peculation and abuse of power, and all that can be said for certain is that the tenth Dalai Lama died just weeks before he was due to turn 21, assume the full powers of his office and dispense with the need for a regent.

The eleventh Dalai Lama did not live so long. Khedup Gyatso also died at the Potala–this time, it was said, of a breakdown in his health caused by the rigors of his training and the punishing round of rituals over which he was supposed to preside. Once again, there is no proof that this death was anything other than natural; once again, however, the situation was unusual. He died in the midst of a disastrous war between Tibet and the Gurkhas of Nepal, and it is not surprising, in those circumstances, that a struggle for power broke out in Lhasa. As a result, the eleventh Dalai Lama suddenly and unexpectedly became the first in 65 years to assume full political power and rule without a regent. This decision made Khedup a threat to a number of vested interests in the Tibetan capital, and it may have been sufficient to make him a target for assassination.

The twelfth Dalai Lama, Trinle Gyatso, was discovered two years after the eleventh’s death. His childhood involved the usual round of intensive study and visits to outlying monasteries. Enthroned in 1873 at the age of 18, he held power for just over two years before his death, and remained for most of his life under the influence of his Lord Chamberlain, Palden Dhondrup. Dhondrup committed suicide in 1871 as a result of court intrigue, after which his body was decapitated and his head put on public display as a warning. The distraught Dalai Lama was so shocked, Verhaegen says, that “he eschewed all company and wandered about as though demented.” Some date his decline to that period; what is certain is that, wintering in the Potala four years later, he fell ill and died in just two weeks.

Two aspects of his life are outstandingly peculiar. The first, noted in the official biography of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, was that Trinle once experienced a vision of the Lotus Born Guru, who advised him that “if you do not rely on the siddhiu of karmamudra, you will soon die.” Karmamudra means tantric sex, but why the Dalai Lama should have been advised to practice it is as much of a mystery as why he expired after rejecting the guru’s psychical advice. Equally puzzling was his final illness, which did not confine him to his bed. Instead, he was found dead, seated in meditation and facing south.

Trinle was the fourth Dalai Lama to die in one human lifetime, and murder was immediately suspected. The ambans, the pro-Chinese historian Yan Hanzhang writes, ordered that “the remains be kept in the same position and all the objects in the Dalai’s bed chamber in the same place as when the death occurred.” They then had all the dead lama’s attendants locked in jail.

An autopsy proved inconclusive, but, for Yan, the identity of the murderers was obvious: The twelfth Dalai Lama and his three predecessors were all “victims of the power struggles between the big clerical and lay serf-owners in Tibet.” An alternative hypothesis suggests that Chinese intervention in Lhasa was the cause. Trinle had been the first Dalai Lama to be selected by a contested draw from the Golden Urn—that “potent symbol of Qing control,” Maher calls it, that was said in Tibetan proverb to be the “honey on a razor’s edge.” As such, he was viewed as Beijing’s man, and was less popular than his predecessors among Tibet’s high nobility. Many in Lhasa saw that as explanation enough for his death.

The indications that the twelfth Dalai Lama was killed are hardly conclusive, of course; indeed, of the four youths who ruled over the Potala between 1804 and 1875, there is strong evidence only for the murder of the tenth Dalai Lama. What can be said, however, is that the numbers do suggest foul play; the average lifespan of the first eight holders of the office had been more than 50 years, and while two early incarnations had died in their 20s, none before the tenth had failed to reach manhood. Tibet in the early nineteenth century was, moreover, far from the holy land of peaceful Buddhist meditation pictured by romantics. Sam von Schaik, the British Museum’s Tibet expert, points out that it was “a dangerous and often violent place where travelers carried swords, and later guns, at all times”—a theocracy in which monks and monasteries fought among themselves and where “violence might be prolonged for generations by blood feuds in vicious cycles of revenge.” Life was all too often cheap in a place like that—even when the victim was a bodhisattva.

Sources

Ya Hanzhang. The Biographies of the Dalai Lamas. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1991; Perceval Landon. Lhasa: an Account of the Country and People of Central Tibet and of the Progress of the Mission Sent There by the English Government in the Year 1903-4. London, 2 vols.: Hurst & Blackett, 1905; Derek Maher, ‘The Ninth to the Twelfth Dalai Lamas.’ In Martin Brauen (ed). The Dalai Lamas: A Visual History. Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2005; Luciano Petech. Aristocracy and Government in Tibet, 1728-1959. Rome: Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 1973; Luciano Petech. ‘The Dalai-Lamas and Regents of Tibet: A Chronological Study.’ T’oung Pao 2nd series vol.47 (1959); Khetsun Sangpo Rinpoche. ‘Life and times of the Eighth to Twelfth Dalai Lamas.’ The Tibet Journal VII (1982); W.W. Rockhill. The Dalai Lamas of Lhasa and their Relations with the Manchu Emperors of China, 1644-1908. Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, 1998; Sam von Schaik. Tibet: A History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011; Günther Schulemann. Geschichte der Dalai Lamas. Leipzig: Harrasowitz, 1958; Tsepon Shakabpa. Tibet: A Political History. New York: Potala Publications, 1988; Ardy Verhaegen. The Dalai Lamas: the Institution and its History. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld, 2002.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)