Musicians Wage War Against Evil Robots

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/201202100131061930-Nov-3-Syracuse-Herald-Syracuse-NY-470x251.jpg)

After the release of The Jazz Singer in 1927, all bets were off for live musicians who played in movie theaters. Thanks to synchronized sound, the use of live musicians was unnecessary — and perhaps a larger sin, old-fashioned. In 1930 the American Federation of Musicians formed a new organization called the Music Defense League and launched a scathing ad campaign to fight the advance of this terrible menace known as recorded sound.

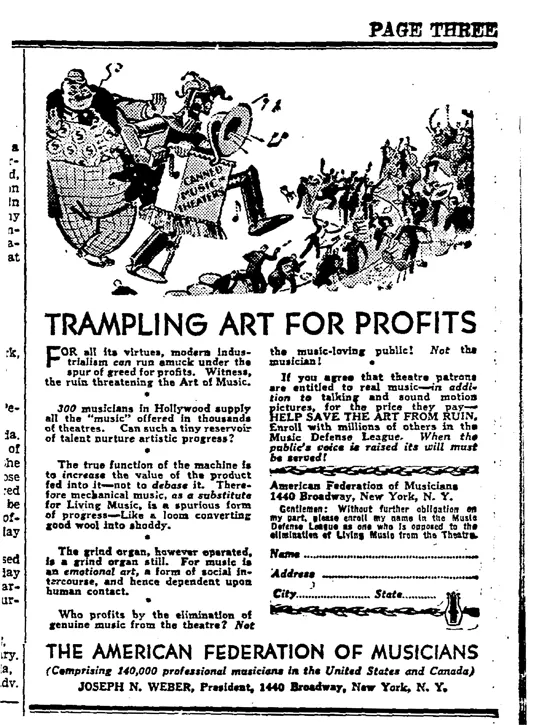

The evil face of that campaign was the dastardly, maniacal robot. The Music Defense League spent over $500,000, running ads in newspapers throughout the United States and Canada. The ads pleaded with the public to demand humans play their music (be it in movie or stage theaters), rather than some cold, unseen machine. A typical ad read like this one from the September 2, 1930 Syracuse Herald in New York:

Tho’ the Robot can make no music of himself, he can and does arrest the efforts of those who can.

Manners mean nothing to this monstrous offspring of modern industrialism, as IT crowds Living Music out of the theatre spotlight.

Though “music has charms to soothe the savage beast, to soften rocks or bend a knotted oak,” it has no power to appease the Robot of Canned Music. Only the theatre-going public can do that.

Hence the swift growth of the Music Defense League, formed to demand Living Music in the theatre.

Every lover of music should join in this rescue of Art from debasement. Sign and mail the coupon.

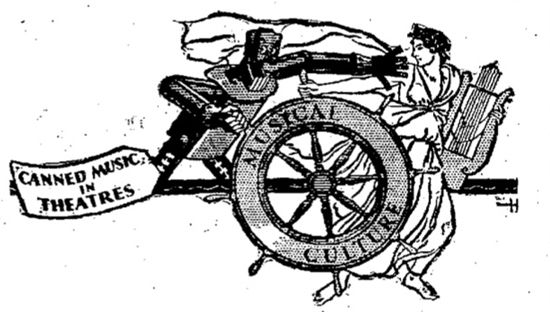

The robot of recorded or “canned” music had many guises, all somehow destroying the best things in society. Here the robot makes a lunge in its attempt to steer “musical culture” away from a decidedly more pure course:

Another ad claimed that musicians were being put out of work by Hollywood because recorded sound required just a few hundred musicians in recording studios. The ad even uses scare quotes around the word “music,” implying that recorded sound couldn’t even be considered as such:

300 musicians in Hollywood supply all the “music” offered in thousands of theatres. Can such a tiny reservoir of talent nurture artistic progress?

Joseph N. Weber, the president of the American Federation of Musicians, made it clear in the March, 1931 issue of Modern Mechanix magazine that the very soul of art was at stake in this battle against the machines:

The time is coming fast when the only living thing around a motion picture house will be the person who sells you your ticket. Everything else will be mechanical. Canned drama, canned music, canned vaudeville. We think the public will tire of mechanical music and will want the real thing. We are not against scientific development of any kind, but it must not come at the expense of art. We are not opposing industrial progress. We are not even opposing mechanical music except where it is used as a profiteering instrument for artistic debasement.

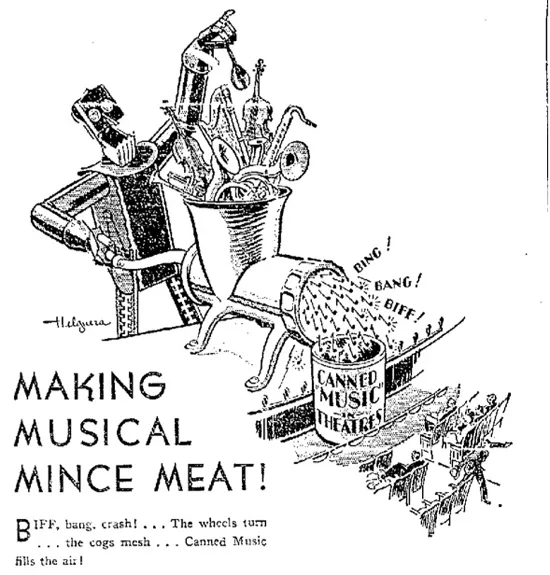

That debasement came in the form of the evil robot grinding up instruments in a meat grinder, like in this ad from the November 3, 1930 Syracuse Herald.

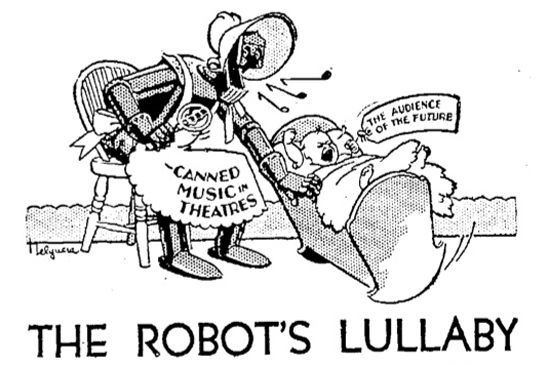

The robot was even shown as a new nurse ineffectively soothing a baby, which represented the audience of the future.

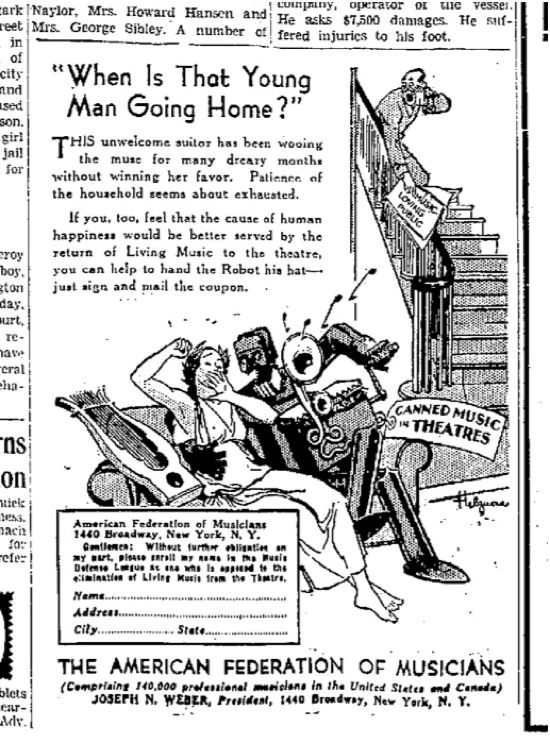

You best hide your daughters, because this ad from the August 24, 1931 Centralia Daily Chronicle in Centralia, Washington shows an “unwelcome suitor” who has been “wooing the muse for many dreary months without winning her favor.”

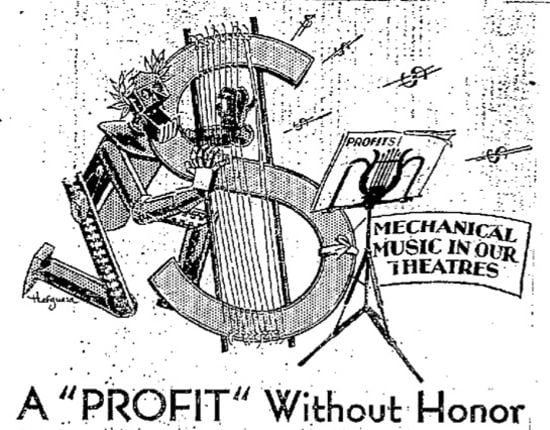

The robot was often shown as greedy in the ads, caring nothing of people but only of profit, like in this ad from the October 1, 1930 Portsmouth Herald (Portsmouth, New Hampshire).

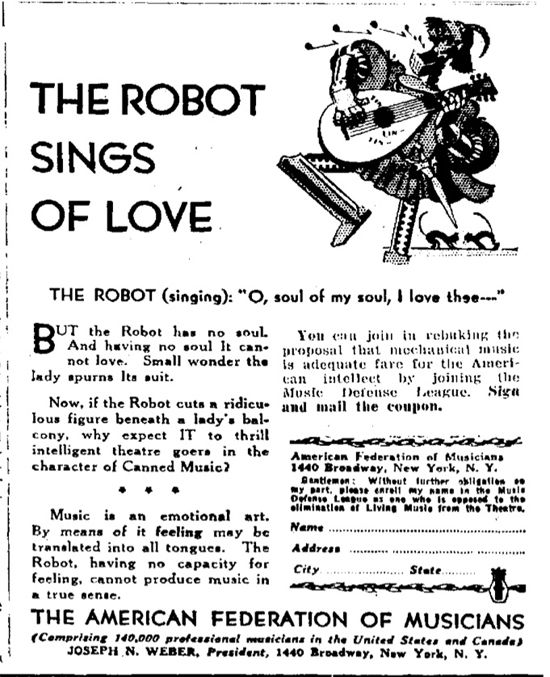

Fundamentally, the ads were an effort to make people believe what made music so special was the musician’s soul that was somehow only reflected in a live performance. This ad from the August 17, 1930 Oelwein Daily Register (Oewlwein, Iowa) got to the heart of it — robots have no soul.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)