New Routes to Old Roots

Twenty-five years after Alex Haley’s best-seller topped the charts, millions of Americans are using high-tech tools to find their ancestors

In the 25 years since Americans sat riveted to their television sets watching Roots—Alex Haley's family biography—genealogy, once considered the precinct of blue-blooded ladies with pearls, has become one of America's most popular hobbies. Experts, writes author Nancy Shute, cite a number of reasons in addition to Roots for this trend, including a growing pride in ethnicity, a proliferation of Internet genealogy sites, and baby boomers' realization that their parents' generation is dwindling.

Today, genealogy buffs by the thousands are flocking to Salt Lake City's Family History Library, the world's largest collection of genealogical records, to search for their ancestors. (The library was established by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or the Mormon Church, to help Mormons find their ancestors and retroactively baptize them in the faith. Now, its files cover more than a hundred countries.) They're also going on-line. Last spring, when author Shute started searching for information about her grandparents, she went to the Ellis Island Archive, which offers a database of the 22 million people who passed through the island and the Port of New York between 1892 and 1924. In short order, she found her grandmother and, later, with additional assistance from the Family History Library, her grandfather's history.

Until recently, despite the popularity of Roots, many African-Americans assumed there was little point in trying to find their own ancestors because there would be no records. But the times are changing. Maria Goodwin, who is historian of the U.S. Mint and teaches African-American genealogy at the Smithsonian's Anacostia Museum, points out that records can be found in old tax rolls and wills of slave owners.

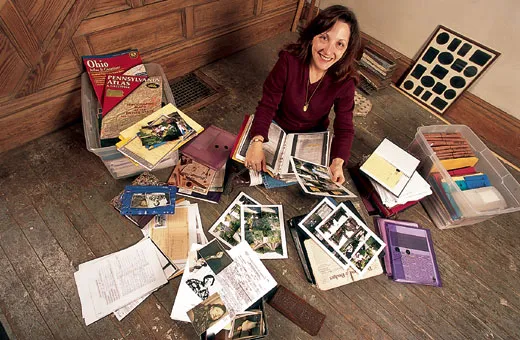

Goodwin also uses the past to point to the future: save as much as possible for tomorrow's genealogists. "Write down your memories and save your photographs," she says. "You think, 'I'm not anyone special,' but you're part of the total picture. We need everyone, not just the heads of corporations. We're all part of the story."