The New York Times’ 1853 Coverage of Solomon Northup, the Hero of “12 Years A Slave”

Northup’s story garnered heavy press coverage and spread widely in the weeks and months after he was rescued

:focal(1266x390:1267x391)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5b/75/5b753dfa-71b2-40ee-8be9-81fec2523ada/solomon_northup.jpg)

This is part of a new series called Vintage Headlines, an examination of notable news from years past.

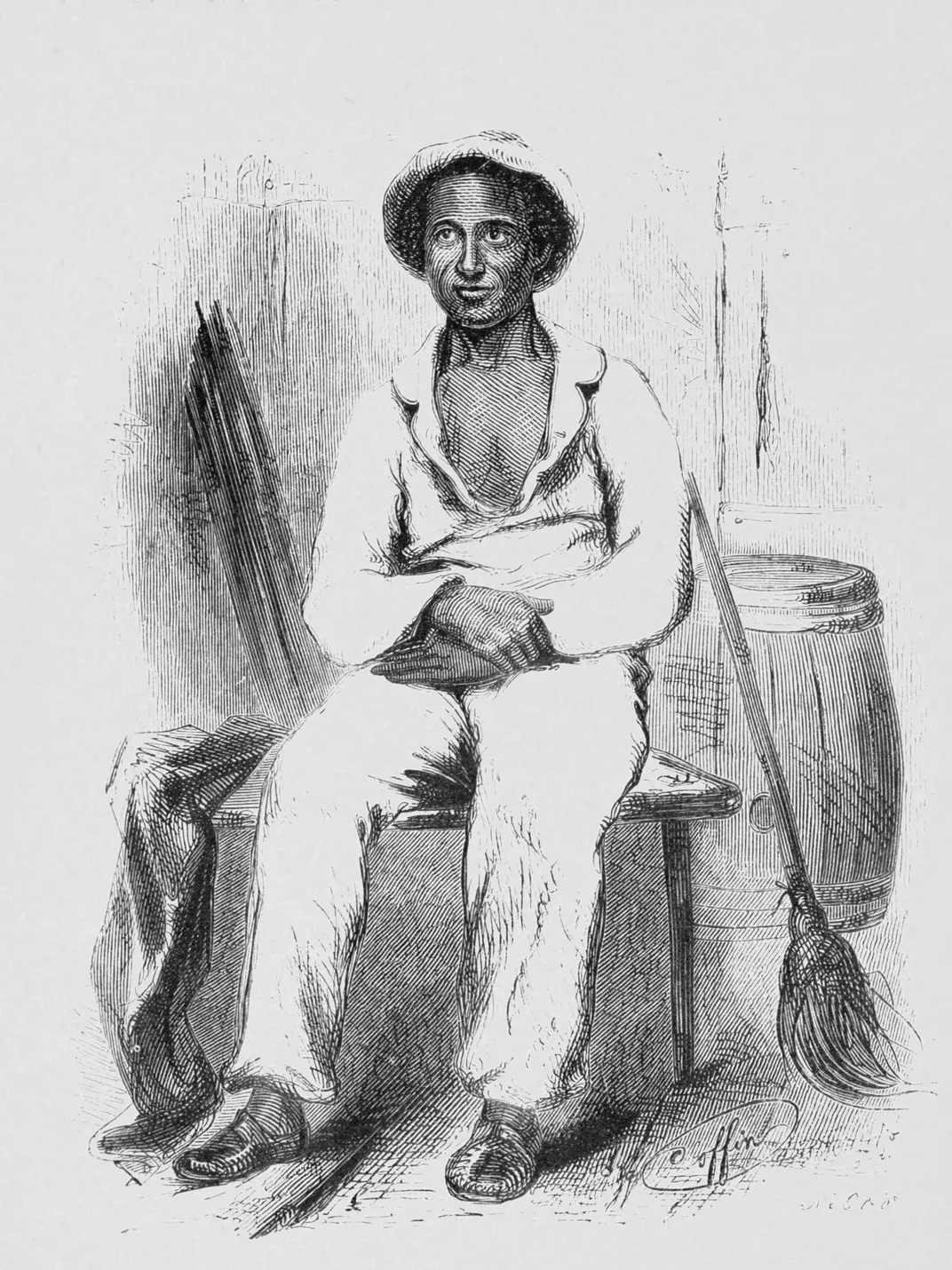

For 12 years, violinist Solomon Northup toiled as a slave in Louisiana in secret, after being kidnapped from his home in Saratoga, New York, and sold for $650. Finally, on January 4, 1853, after an allied plantation worker sent several letters north on his behalf, Northup was freed, and returned home.

For the entire period in between, all his friends and family—including his wife and two young children—had no way of knowing where he was. But it didn't take until this past year's Best Picture winner 12 Years A Slave for his story to once again be widely known.

It was first told in his own book, Twelve Years a Slave (full subtitle: Narrative of Solomon Northup, citizen of New-York, kidnapped in Washington city in 1841, and rescued in 1853, from a cotton plantation near the Red River in Louisiana). But even before that, mere weeks after his freedom was restored, Northup's case was getting major press coverage—as in this January 20, 1853 New York Times article:

Despite misspelling Northup's last name in two different ways, the article tells the story of his brutal kidnapping in accurate and lurid detail, beginning with his assault in a Washington, DC, hotel, after he was brought there to perform in a traveling circus and drugged:

While suffering with severe pain some persons came in, and, seeing the condition he was in, proposed to give him some medicine and did so. That is the last thing of which he had any recollection until he found himself chained to the floor of Williams' slave pen in this city, and handcuffed. In the course of a few hours, James H. Burch, a slave dealer, came in, and the colored man asked him to take the irons off from him, and wanted to know why they were put on. Burch told him it was none of his business. The colored man said he was free and told where he was born. Burch called in a man by the name of Ebenezer Rodbury, and they two stripped the man and laid him across a bench, Rodbury holding him down by his wrists. Burch whipped him with a paddle until he broke that, and then with a cat-o'-nine-tails, giving him a hundred lashes, and he swore he would kill him if he ever stated to anyone that he was a free man.

(Update, March 4: 151 years after publishing the article, the Times corrected the spelling errors.)

The article goes on to cover Northup's unlikely rescue, and the 1853 legal proceedings against Burch and the others involved in the kidnapping, noting the fact that during the trial, Northup was unable to take the stand, because Washington law prohibited black witnesses from testifying against white defendants. The owners of the plantations where he'd worked, meanwhile, were fully protected from prosecution:

By the laws of Louisiana no man can be punished there for having sold Solomon into slavery wrongfully, because more than two years had elapsed since he was sold; and no recovery can be had for his services, because he was bought without the knowledge that he was a free citizen.

Ultimately, Burch was acquitted, because he claimed he'd thought Northup was truly a slave for sale, and Northup couldn't testify otherwise. The identities of the two men who'd originally brought Northup to Washington on business and proceeded to drug and sell him remained a mystery.

The next year, however, a New York state judge happened to recall seeing a pair of white men travel to Washington with Northup and return without him: Alexander Merrill and Joseph Russell. In July 1854, a case was brought against them in New York—where Northup was allowed to testify—and the Times covered it with a pair of short pieces.

Northup distinctly swears to their being the persons—and told how he was hired at Saratoga Springs in 1841, to go South with them to join a Circus, and treated in Washington with drugged liquor, &c., &c.

Sadly, Northup was unable to bring Merrill or Russell to justice; after two years of appeals, the charges were dropped for unclear reasons.

Northup's memoir went on to sell 30,000 copies. In April 1853, the Times covered this book too, in a brief note on new titles to be published in the spring.

Buried amidst descriptions of new editions of British poetry, the newspaper devoted 11 lines of text to Northup's new title, "a full story of his life and sufferings on the Cotton plantation." The last, blunt sentence has proven most prescient: "It will be read widely."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)