Making the Case for the Next American Saint

Sister Blandina Segale showed true grit while caring for orphans and outlaws in New Mexico

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/58/de/58de0242-c581-408e-8b15-f16529259285/nov2016_e03_colnun-wr.jpg)

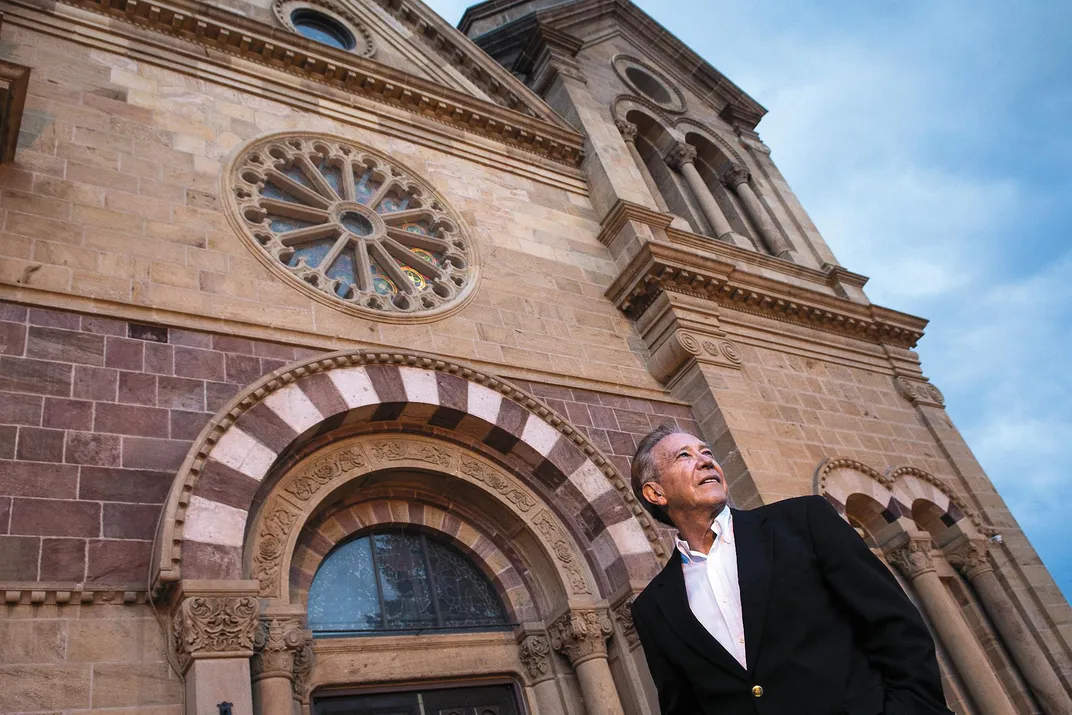

Peso Chavez, private eye, sat at his oval laminate conference table, beneath a framed print of bright autumn trees, in a low-slung adobe-style office park, under a streaked robin’s-egg dome of New Mexico sky. He was looking cool and unflappable: black blazer, black Ray-Bans, swept-back gray hair, spotless blue jeans.

Chavez is an institution in Santa Fe, an attorney, former city councilman, one-time mayoral candidate. His family dates its New Mexico roots back 400 years when the first Spanish settlers came to the region; he’s now one of the most respected investigators in the state. He specializes in criminal defense, civil suits and death penalty cases, and estimates that he has interviewed some 40,000 people over the course of his career. “In 43 years of investigative work,” he said, “I thought I had seen everything I could ever see in humanity.”

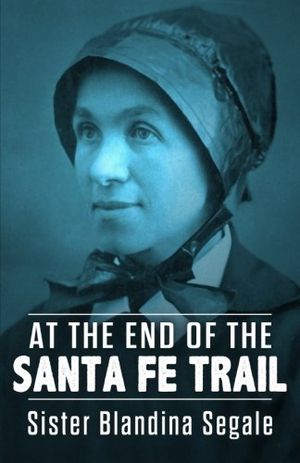

But last spring, Chavez took a case that gave him pause. The investigation involved a lunatic, a lynch mob, a lead-riddled Irishman, a stagecoach, a revolver-toting Jewish merchant, a freed slave, a rearing bronco, Billy the Kid, and an intrepid Catholic nun. The target of the case was the nun—a tiny but larger-than-life Sister of Charity named Blandina Segale, who was stationed in Santa Fe and Trinidad, Colorado, in the 1870s and 1880s. Blandina is beloved in New Mexico Catholic circles. Her adventures in the Southwest were immortalized in At the End of the Santa Fe Trail, a collection of letters she wrote to her sister that was published as a book in 1932. She was later celebrated in midcentury comic books and on the 1966 TV show “Death Valley Days,” which memorably dubbed her “The Fastest Nun in the West.”

Now Sister Blandina is in the process of being vetted for sainthood—the first in the New Mexico church’s 418-year history. That’s how Peso Chavez got involved. Blandina’s admirers hired him to help make the case. “This was the most ominous, humbling investigation I ever did,” Chavez said. “I was shaking in my boots.”

He wheeled his chair back from the conference table and waved one black alligator cowboy boot in the air. “Literally, in my boots.”

**********

Sister Blandina was born Maria Rosa Segale in the mountains near Genoa, in northern Italy, in 1850, and moved with her family to Cincinnati at the age of 4. At 16, she took her vows with the Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati; in 1872, she boarded a stagecoach to Trinidad, Colorado, to begin life as a missionary. It was a demanding posting for a young woman traveling alone to a territory that had been a part of Mexico only 24 years before and was now home to fortune-seekers, soldiers, Civil War veterans, freed slaves, uprooted natives, cowboys, farmers and, Blandina wrote, “men with money looking to become millionaires, land-grabbers, experienced and inexperienced miners, quacks, professional deceivers, publicity men lauding gold mines that do not exist.”

Chavez said, “There was no law and order. The guy with the most guns and the fastest horse could do what he wanted to do.”

But Blandina was forceful and plucky, and she quickly made her mark, tending to the ill, educating the poor, building schools and hospitals, and speaking up for the rights of Hispanics and displaced Indians. “When she saw a need,” said Allen Sánchez, who hired Chavez to look into her life, “she served it.”

Sánchez is Blandina’s principal champion, a sunny, clean-cut former seminarian who wears a Vaticano pin on his lapel and his enthusiasm for Blandina, equally, on his sleeve. Sánchez grew up in a small town south of Albuquerque, one of 12 siblings. He first learned about Sister Blandina as a child—all Catholic children in New Mexico did. He struggled with learning disabilities, learning to read only in tenth grade, but went on to study for the priesthood in Rome, receiving advanced degrees in theology and spirituality. He was two weeks from ordination in 1993 when Cardinal John O’Connor let him know that a sex scandal—the first of many in New Mexico—would force the state’s archbishop to resign. Sánchez postponed ordination and ultimately decided that his calling was not as a priest, but to serve the poor. He went on to direct a ministry of small faith-sharing groups, and serves as the New Mexico bishops’ chief lobbyist, where he has been a tireless advocate in the state legislature for immigrants and children born into poverty.

In 2008, he became president of CHI St. Joseph’s Children, a Catholic charity. The group had sold Albuquerque’s St. Joseph hospital, an institution Blandina had founded. As the organization struggled to reinvent itself as a community health service, Sánchez reread Blandina’s book and came to “the beautiful conclusion” that the group should fund an army of women to provide weekly home visits to low-income mothers and babies—“modern-day Blandinas” who serve the poorest children in one of the nation’s poorest states. “Her book is alive in us,” he says, “and in what we’re doing.”

To repay that inspiration, the group also resolved to pursue the designation of sainthood for Blandina. There are currently dozens of active American sainthood petitions, and many have languished for years. Blandina’s initial petition to the Vatican moved quickly, however. On June 29, 2014, her “cause” was officially opened.

The process began with a visit to Blandina’s grave in Cincinnati (she returned to her home convent in 1893 and died in 1941). There, Sánchez and other members of the inquiry board ascertained that Blandina was in fact “good and dead,” he said. Then began an elaborate ritual of petitions and decrees and juridical citations, of transcripts and depositions and postulators and notaries and theological censors scrutinizing Blandina’s words and deeds. It is, Sánchez explains, something like a secular grand jury proceeding—except “they examine your whole life.”

That’s where Peso Chavez came in. “We needed someone who had a good idea of how to use government records,” Sánchez said. Chavez, along with two nuns in Cincinnati, was named to a historical commission charged with documenting Blandina’s “heroic virtues”—the good works she performed during her life. While the nuns went through her possessions and letters at their Cincinnati headquarters, Chavez pursued evidence of Blandina’s charitable acts in the Southwest.

Chavez focused first on an event that Blandina chronicled. It began, she wrote, when a boy named John came to fetch his sister from Blandina’s schoolroom in Trinidad. “He looked so deathly pale that I inquired, ‘What has happened?’”

What had happened was that John’s father had shot a man in the leg. The gun had been loaded with buckshot, and the victim was slowly dying. John’s father was sitting in jail as a mob gathered outside, waiting for the man to die so they could hang his killer.

Blandina abhorred such violence. So she hatched a plan: She convinced the dying “young Irishman” to forgive his shooter. Fearing that the mob would “tear [the shooter] to pieces before he was ten feet from the jail,” she walked the prisoner, “trembling like an aspen,” past the angry crowd. “Intense fear took possession of me,” Blandina wrote. They continued into the sickroom, where the killer bowed his head: “‘My boy, I did not know what I was doing. Forgive me.’”

“I forgive you,” the dying man replied, and the prisoner remained safe until a judge arrived to convene a trial and send him to prison.

Sánchez believed that this incident provided a powerful demonstration of Blandina’s charity and courage. How, though, to separate the myths of the West from the truths of the past and prove that the event had actually happened? “What you want to do,” said Chavez, “is make sure that these facts are, in fact, facts.” To elevate a historical woman to the status of saint, her supporters’ first task was, ironically, to deconstruct the myths around her.

There wasn’t much to go on. Chavez read Blandina’s book carefully, searching for clues. “The boy named John was very, very important for me.” He also had the date Blandina wrote about the shooting: November 14, 1875.

He consulted local newspapers from that winter. He found evidence of lawlessness, such as a report of a hanging that was held within hours of the crime (by a mob of women, no less); and hand-wringing articles about Trinidad’s “rowdyism.” But he found no particular events resembling Blandina’s story.

He looked for court records. The town sheriff’s files were nowhere to be found. But Blandina had also mentioned a territorial circuit judge, Moses Hallett. “I said, Aha! Now I’ve got it!” Chavez drove his truck to the federal archives in Denver where the territorial court records should have been stored: “There was absolutely nothing.”

He headed to the territorial penitentiary archives in Cañon City, Colorado, hoping to find some record of a prisoner admitted from Trinidad in 1874. And there, “lo and behold,” he found Judge Hallett’s misplaced criminal docket—and in it, in looping Victorian script, he also found a name: Morris James, Cañon City Territorial Prisoner number 67, convicted of murder in Trinidad on July 3, 1875. The event had happened months before Blandina wrote about it. With that information, Chavez went back to the newspapers: In March 1875, Morris James, a miner with two daughters and a son named John, got drunk, borrowed a shotgun, and went “up the arroyo to shoot an Irishman.” James likely suffered from mental illness; he was pardoned and sent to a “lunatic asylum” in April 1876.

Later, the nuns in Cincinnati uncovered a letter from the shooter’s daughter, written years later, praising Blandina for her “loving, dauntless, courageous heart.” This was “corroborating evidence,” Chavez explained: Blandina had saved a life, and perhaps a soul. This “little girl,” 22 years old and barely five feet tall, had stood up “to these big guys with guns. That’s important in the context of her virtues.”

**********

Chavez also investigated Sister Blandina’s alleged run-in with a much more famous criminal: Billy the Kid. That’s how I first met Sánchez and Chavez. I had stumbled upon Blandina’s memoirs when I was researching American Ghost, a book about my German Jewish ancestors who had settled in New Mexico in the middle of the 19th century. In 1877, shortly after Blandina moved from Trinidad to Santa Fe, she crossed paths with them. My great-great-grandfather, a prosperous merchant named Abraham Staab, had befriended Jean-Baptiste Lamy, New Mexico’s first archbishop, whose life on the desert frontier was fictionalized in Willa Cather’s novel Death Comes for the Archbishop. Abraham’s wife, Julia, was severely depressed, and Abraham asked Lamy for help tending to her. The task fell to Blandina. “I have no attraction for entertaining wealthy ladies,” she wrote. But she cared for Julia and her children for some weeks, and then traveled with them to the railroad’s end in Trinidad to put them on a train to New York.

Abraham and Sister Blandina then headed back to Santa Fe on a speedy four-horse “hack” carriage. It was a dangerous time on the trail. Billy the Kid’s gang, Abraham warned, was raiding settlements, stealing horses and attacking “coaches or anything of profit that comes in his way.” But Blandina told Abraham that she had “very little fear of Billy’s gang.” She had come to know them months earlier, when she nursed one of Billy’s gang members as he died. “At any time my pals and I can serve you,” Billy had told her, “you will find us ready.”

Now was such a time. On the second afternoon of their trip, Abraham’s driver yelled into the carriage that a man was speeding toward them on his horse. Abraham and another man in the coach took out their revolvers. The rider came closer. “By this time both gentlemen were feverishly excited,” Blandina recalled. But when Billy approached Blandina’s carriage, she advised Abraham to put down his gun. A “light patter of hoofs” drew near, and Blandina shifted her bonnet so the outlaw could see her: “Our eyes met, he raised his large-brimmed hat with a wave and a bow, looked his recognition, fairly flew a distance of about three rods, and then stopped to give us some of his wonderful antics on bronco maneuvers.” Free of outlaws, Blandina and the coach barreled on. “We made the fastest trip ever known from Trinidad to Santa Fe,” she wrote. She was, indeed, the fastest nun in the West.

Chavez’s research was complicated by the fact that there were two Billy the Kids roaming the high desert in 1877: William Bonney, the famous Billy, who did much of his outlawing in southern New Mexico and eastern Arizona, and William LeRoy—the not-so-famous Billy—who terrorized northern New Mexico. Chavez created a chart tracking dates and Billy-sightings, and determined that it was likely the second Billy who spared my great-great-grandfather thanks to Blandina’s intervention. When Sánchez and I appeared on a radio show together about Sister Blandina and he learned of my research, he put me in touch with Chavez, who interviewed me to ascertain that Abraham Staab and his despondent wife, Julia, did, in fact, exist; that Blandina helped all comers.

“Did she live those virtues of faith, hope and charity?” asked Father Oscar Coelho, a priest and canon lawyer who conducted the depositions for the inquiry. “For me,” he said, “she did.”

**********

Last fall, Michael Sheehan, New Mexico’s recently retired archbishop, decreed that there was sufficient evidence of Blandina’s virtues, and Sánchez traveled to Rome with a 2,000-page packet for the Vatican’s theologians to review. Now Blandina must produce two verifiable miracles, such as helping cancer patients who pray to her, or saving immigrants from deportation. “It’s harder today to prove a miracle,” Sánchez says. His team is now investigating numerous possible miracles (they remain confidential until proven), and if they pass initial muster, each will have its own hearing, depositions and, in the case of medical miracles, panels of doctors. One woman reported seeing the face of Jesus in a tortilla after praying to Blandina; Sánchez decided not to pursue that one.

In the meantime, the New Mexico archdiocese is planning a restoration of the Albuquerque convent Blandina built and the nearby adobe church, which will house a shrine and some of Blandina’s relics if the Vatican agrees that Blandina should be “venerated,” the first formal step toward sainthood. This could happen within a year. “The pope likes her,” says Sánchez.

Sainthood is, however, more controversial than it used to be. The 2015 canonization of Father Junípero Serra, who established the first Catholic missions in California, proved contentious: Many hold him responsible for the harsh treatment of Native Americans there. Mother Teresa, who was elevated to sainthood this past September, has been accused of secretly baptizing dying Hindu and Muslim patients, and accepting donations from criminals and dictators.

Sister Blandina has her unsettling moments as well. While she championed native populations—“Generations to come will blush for the deeds of this, toward the rightful possessors of the soil,” she wrote—she also lamented their “unevolved minds.” In recounting the incident with Billy the Kid, her efforts to capture the dialect of the “darkey” (her word) on the stagecoach are disconcerting: “Massah, there am som-un skimming over the plains, coming dis way.”

Still, Sánchez believes Blandina carries a “message for today”—hope for the vulnerable, help for immigrants, health care for all, compassion for those on the margins. “From the most innocent to the most guilty, she helped them all,” Sánchez says. She is, he says, a saint for our time. “New Mexico is in such bad shape. We need miracles. We need a saint.”

At the End of the Santa Fe Trail