Nikita Khrushchev Goes to Hollywood

Lunch with the Soviet leader was Tinseltown’s hottest ticket, with famous celebrities including Marilyn Monroe and Dean Martin

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Nikita-Khrushchev-watching-Can-Can-631.jpg)

Fifty summers ago President Dwight Eisenhower, hoping to resolve a mounting crisis over the fate of Berlin, invited Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to a summit meeting at Camp David. Ike had no idea of what he was about to unleash on the land whose Constitution he had sworn to defend.

It was the height of the cold war, a frightening age of fallout shelters and "duck-and-cover" drills. No Soviet premier had visited the United States before, and most Americans knew little about Khrushchev except that he had jousted with Vice President Richard Nixon in the famous "kitchen debate" in Moscow that July and had uttered, three years before, the ominous-sounding prediction, "We will bury you."

Khrushchev accepted Ike's invitation—and added that he'd also like to travel around the country for a few weeks. Ike, suspicious of the wily dictator, reluctantly agreed.

Reaction to the invitation was mixed, to say the least. Hundreds of Americans bombarded Congress with angry letters and telegrams of protest. But hundreds of other Americans bombarded the Soviet Embassy with friendly pleas that Khrushchev visit their home or their town or their county fair. "If you'd like to enter a float," the chairman of the Minnesota Apple Festival wrote to Khrushchev, "please let us know."

A few days before the premier's scheduled arrival, the Soviets launched a missile that landed on the moon. It was the first successful moonshot, and it caused a massive outbreak of UFO sightings in Southern California. That was only a prelude to a two-week sojourn that historian John Lewis Gaddis would characterize as "a surreal extravaganza."

After weeks of hype—"Khrushchev: Man or Monster?" (New York Daily News), "Capital Feverish on Eve of Arrival" (New York Times), "Official Nerves to Jangle in Salute to Khrushchev" (Washington Post), "Khrushchev to Get Free Dry Cleaning" (New York Herald Tribune)—Khrushchev landed at Andrews Air Force base on September 15, 1959. Bald as an egg, he stood only a few inches over five feet but weighed nearly 200 pounds, and he had a round face, bright blue eyes, a mole on his cheek, a gap in his teeth and a potbelly that made him look like a man shoplifting a watermelon. When he stepped off the plane and shook Ike's hand, a woman in the crowd exclaimed, "What a funny little man!"

Things got funnier. As Ike read a welcoming speech, Khrushchev mugged shamelessly. He waved his hat. He winked at a little girl. He theatrically turned his head to watch a butterfly flutter by. He stole the spotlight, one reporter wrote, "with the studied nonchalance of an old vaudeville trouper."

The traveling Khrushchev roadshow had begun.

The next day, he toured a farm in Maryland, where he petted a pig and complained that it was too fat, then grabbed a turkey and griped that it was too small. He also visited the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and advised its members to get used to communism, drawing an analogy with one of his facial features: "The wart is there, and I can't do anything about it."

Early the next morning, the premier took his show to New York City, accompanied by his official tour guide, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., the United States ambassador to the United Nations. In Manhattan, Khrushchev argued with capitalists, yelled at hecklers, shadowboxed with Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, got stuck in an elevator in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel and toured the Empire State Building, which failed to impress him.

"If you've seen one skyscraper," he said, "you've seen them all."

And on the fifth day, the cantankerous communist flew to Hollywood. There, things only got weirder.

Twentieth Century Fox had invited Khrushchev to watch the filming of Can-Can, a risqué Broadway musical set among the dance hall girls of fin de siècle Paris, and he had accepted. It was an astounding feat: a Hollywood studio had persuaded the communist dictator of the world's largest nation to appear in a shameless publicity stunt for a second-rate musical. The studio sweetened the deal by arranging for a luncheon at its elegant commissary, the Café de Paris, where the great dictator could break bread with the biggest stars in Hollywood. But there was a problem: only 400 people could fit into the room, and nearly everybody in Hollywood wanted to be there.

"One of the angriest social free-for-alls in the uninhibited and colorful history of Hollywood is in the making about who is to be at the luncheon," Murray Schumach wrote in the New York Times.

The lust for invitations to the Khrushchev lunch was so strong that it overpowered the fear of communism that had reigned in Hollywood since 1947, when the House Committee on Un-American Activities began investigating the movie industry, inspiring a blacklist of supposed communists that was still enforced in 1959. Producers who were scared to death of being seen snacking with a communist screenwriter were desperate to be seen dining with the communist dictator.

A handful of stars—Bing Crosby, Ward Bond, Adolphe Menjou and Ronald Reagan—turned down their invitations as a protest against Khrushchev, but not nearly enough to make room for the hordes who demanded one. Hoping to ease the pressure, 20th Century Fox announced that it would not invite agents or the stars' spouses. The ban on agents crumbled within days, but the ban on spouses held. The only husband-and-wife teams invited were those in which both members were stars—Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh; Dick Powell and June Allyson; Elizabeth Taylor and Eddie Fisher. Marilyn Monroe's husband, the playwright Arthur Miller, might have qualified as a star, but he was urged to stay home because he was a leftist who'd been investigated by the House committee and therefore was considered too radical to dine with a communist dictator.

However, the studio was determined that Miller's wife attend. "At first, Marilyn, who never read the papers or listened to the news, had to be told who Khrushchev was," Lena Pepitone, Monroe's maid, recalled in her memoirs. "However, the studio kept insisting. They told Marilyn that in Russia, America meant two things, Coca-Cola and Marilyn Monroe. She loved hearing that and agreed to go....She told me that the studio wanted her to wear the tightest, sexiest dress she had for the premier."

"I guess there's not much sex in Russia," Marilyn told Pepitone.

Monroe arrived in Los Angeles a day ahead of Khrushchev, flying from New York, near where she and Miller were then living. When she landed, a reporter asked if she'd come to town just to see Khrushchev.

"Yes," she said. "I think it's a wonderful thing, and I'm happy to be here."

That provoked the inevitable follow-up question: "Do you think Khrushchev wants to see you?"

"I hope he does," she replied.

The next morning, she arose early in her bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel and began the complex process of becoming Marilyn Monroe. First, her masseur, Ralph Roberts, gave her a rubdown. Then hairdresser Sydney Guilaroff did her hair. Then makeup artist Whitey Snyder painted her face. Finally, as instructed, she donned a tight, low-cut black patterned dress.

In the middle of this elaborate project, Spyros Skouras, the president of 20th Century Fox, dropped by to make sure that Monroe, who was notorious for being late, would arrive at this affair on time.

"She has to be there," he said.

And she was. Her chauffeur, Rudi Kautzsky, delivered her to the studio. When they found the parking lot nearly empty, she was scared.

"We must be late!" she said. "It must be over."

It wasn't. For perhaps the first time in her career, Marilyn Monroe had arrived early.

Waiting for Khrushchev to arrive, Edward G. Robinson sat at table 18 with Judy Garland and Shelley Winters. Robinson puffed on his cigar and gazed out at the kings and queens of Hollywood—the men wearing dark suits, the women in designer dresses and shimmering jewels. Gary Cooper was there. So was Kim Novak. And Dean Martin, Ginger Rogers, Kirk Douglas, Jack Benny, Tony Curtis and Zsa Zsa Gabor.

"This is the nearest thing to a major Hollywood funeral that I've attended in years," said Mark Robson, the director of Peyton Place, as he eyeballed the scene.

Marilyn Monroe sat at a table with producer David Brown, director Joshua Logan and actor Henry Fonda, whose ear was stuffed with a plastic plug that was attached to a transistor radio tuned to a baseball game between the Los Angeles Dodgers and the San Francisco Giants, who were fighting for the National League pennant.

Debbie Reynolds sat at table 21, which was located—by design—across the room from table 15, which was occupied by her ex-husband Eddie Fisher and his new wife, Elizabeth Taylor, who had been Reynolds' close friend until Fisher left her for Taylor.

The studio swarmed with plainclothes police, both American and Soviet. They inspected the shrubbery outside, the flowers on each table and both the men's and women's rooms. In the kitchen, an LAPD forensic chemist named Ray Pinker ran a Geiger counter over the food. "We're just taking precautions against the secretion of any radioactive poison that might be designed to harm Khrushchev," Pinker said before heading off to check the soundstage where the premier would watch the filming of Can-Can.

As Khrushchev's motorcade pulled up to the studio, the stars watched live coverage of his arrival on televisions that had been set up around the room, their knobs removed so nobody could change the channel to the Dodgers-Giants game. They saw Khrushchev emerge from a limo and shake hands with Spyros Skouras.

A few moments later, Skouras led Khrushchev into the room and the stars stood to applaud. The applause, according to the exacting calibrations of the Los Angeles Times, was "friendly but not vociferous."

Khrushchev took a seat at the head table. At an adjacent table, his wife, Nina, sat between Bob Hope and Frank Sinatra. Elizabeth Taylor climbed on top of table 15 so she could get a better look at the dictator.

As the waiters delivered lunch—squab, wild rice, Parisian potatoes and peas with pearl onions—Charlton Heston, who'd once played Moses, attempted to make small talk with Mikhail Sholokhov, the Soviet novelist who would win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1965. "I have read excerpts from your works," Heston said.

"Thank you," Sholokhov replied. "When we get some of your films, I shall not fail to watch some excerpts from them."

Nearby, Nina Khrushchev showed Frank Sinatra and David Niven pictures of her grandchildren and bantered with cowboy star Gary Cooper, one of the few American actors she'd actually seen on-screen. She told Bob Hope that she wanted to see Disneyland.

As Henry Cabot Lodge ate his squab, Los Angeles Police Chief William Parker suddenly appeared behind him, looking nervous. Earlier, when Khrushchev and his entourage had expressed interest in going to Disneyland, Parker had assured Lodge that he could provide adequate security. But during the drive from the airport to the studio, somebody threw a big, ripe tomato at Khrushchev's limo. It missed, splattering the chief's car instead.

Now, Parker leaned over and whispered into Lodge's ear. "I want you, as a representative of the president, to know that I will not be responsible for Chairman Khrushchev's safety if we go to Disneyland."

That got Lodge's attention. "Very well, Chief," he said. "If you will not be responsible for his safety, we do not go, and we will do something else."

Someone in Khrushchev's party overheard the conversation and immediately got up to tell the Soviet leader that Lodge had canceled the Disneyland trip. The premier sent a note back to the ambassador: "I understand you have canceled the trip to Disneyland. I am most displeased."

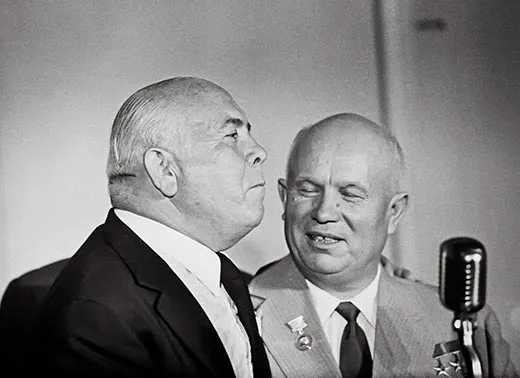

When the waiters had cleared away the dishes, Skouras stood up to speak. Short, stocky and bald, Skouras, 66, looked a lot like Khrushchev. With a gravelly voice and a thick accent, he also sounded a lot like Khrushchev. "He had this terrible Greek accent—like a Saturday Night Live put-on," recalled Chalmers Roberts, who covered Khrushchev's U.S. tour for the Washington Post. "Everybody was laughing."

Khrushchev listened to Skouras for a while, then turned to his interpreter and whispered, "Why interpret for me? He needs it more."

Skouras may have sounded funny, but he was a serious businessman with a classic American success story. Son of a Greek shepherd, he had immigrated to America at 17, settling in St. Louis, where he sold newspapers, bused tables and saved his money. With two brothers, he invested in a movie theater, then another, and another. By 1932, he was managing a chain of 500 theaters. A decade later, he was running 20th Century Fox. "In all modesty, I beg you to look at me," he said to Khrushchev from the dais. "I am an example of one of those immigrants who, with my two brothers, came to this country. Because of the American system of equal opportunities, I am now fortunate enough to be president of 20th Century Fox."

Like so many other after-dinner orators on Khrushchev's trip, Skouras wanted to teach him about capitalism: "The capitalist system, or the price system, should not be criticized, but should be carefully analyzed—otherwise America would never have been in existence."

Skouras said he'd recently toured the Soviet Union and found that "warm-hearted people were sorrowful for the millions of unemployed people in America." He turned to Khrushchev. "Please tell your good people there is no unemployment in America to worry about."

Hearing that, Khrushchev could not resist heckling. "Let your State Department not give us these statistics about unemployment in your country," he said, raising his palms in a theatrical gesture of befuddlement. "I'm not to blame. They're your statistics. I'm only the reader, not the writer."

That got a laugh from the audience.

"Don't believe everything you read," Skouras shot back. That got a laugh, too.

When Skouras sat down, Lodge stood up to introduce Khrushchev. While the ambassador droned on about America's alleged affection for Russian culture, Khrushchev heckled him, plugging a new Soviet movie.

"Have you seen They Fought for Their Homeland?" the premier called out. "It is based on a novel by Mikhail Sholokhov."

"No," Lodge said, a bit taken aback.

"Well, buy it," said Khrushchev. "You should see it."

Smiling, the dictator stepped to the dais and invited the stars to visit the Soviet Union: "Please come," he said. "We will give you our traditional Russian pies."

He turned to Skouras—"my dear brother Greek"—and said he was impressed by his capitalist rags-to-riches story. But then he topped it with a communist rags-to-riches story. "I started working as soon as I learned how to walk," he said. "I herded cows for the capitalists. That was before I was 15. After that, I worked in a factory for a German. Then I worked in a French-owned mine." He paused and smiled. "Today, I am the premier of the great Soviet state."

Now it was Skouras' turn to heckle. "How many premiers do you have?"

"I will answer that," Khrushchev replied. He was premier of the whole country, he said, and then each of the 15 republics had its own premier. "Do you have that many?"

"We have two million American presidents of American corporations," Skouras replied.

Score one for Skouras! Of course, Khrushchev was not willing to concede anything.

"Mr. Tikhonov, please rise," the premier ordered.

At a table in the audience, Nikolai Tikhonov stood up.

"Who is he?" Khrushchev asked. "He is a worker. He became a metallurgical engineer....He is in charge of huge chemical factories. A third of the ore mined in the Soviet Union comes from his region. Well, Comrade Greek, is that not enough for you?"

"No," Skouras shot back. "That's a monopoly."

"It is a people's monopoly," Khrushchev replied. "He does not possess anything but the pants he wears. It all belongs to the people!"

Earlier, Skouras had reminded the audience that American aid helped fight a famine in the Soviet Union in 1922. Now, Khrushchev reminded Skouras that before the Americans sent aid, they sent an army to crush the Bolshevik revolution. "And not only the Americans," he added. "All the capitalist countries of Europe and of America marched upon our country to strangle the new revolution. Never have any of our soldiers been on American soil, but your soldiers were on Russian soil. These are the facts."

Still, Khrushchev said, he bore no ill will. "Even under those circumstances," he said, "we are still grateful for the help you rendered."

Khrushchev then recounted his experiences fighting in the Red Army during the Russian civil war. "I was in the Kuban region when we routed the White Guard and threw them into the Black Sea," he said. "I lived in the house of a very interesting bourgeois intellectual family."

Here he was, Khrushchev went on, an uneducated miner with coal dust still on his hands, and he and other Bolshevik soldiers, many of them illiterate, were sharing the house with professors and musicians. "I remember the landlady asking me: ‘Tell me, what do you know about ballet? You're a simple miner, aren't you?' To tell the truth, I didn't know anything about ballet. Not only had I never seen a ballet, I had never seen a ballerina."

The audience laughed.

"I did not know what sort of dish it was or what you ate it with."

That brought more laughter.

"And I said, ‘Wait, it will all come. We will have everything—and ballet, too.'"

Even the tireless Red-bashers of the Hearst press conceded that "it was almost a tender moment." But of course Khrushchev could not stop there. "Now I have a question for you," he said. "Which country has the best ballet? Yours? You do not even have a permanent opera and ballet theater. Your theaters thrive on what is given to them by rich people. In our country, it is the state that gives the money. And the best ballet is in the Soviet Union. It is our pride."

He rambled on, then apologized for rambling. After 45 minutes of speaking, he seemed to be approaching an amiable closing. Then he remembered Disneyland.

"Just now, I was told that I could not go to Disneyland," he announced. "I asked, ‘Why not? What is it? Do you have rocket-launching pads there?' "

The audience laughed.

"Just listen," he said. "Just listen to what I was told: ‘We—which means the American authorities—cannot guarantee your security there.' "

He raised his hands in a vaudevillian shrug. That got another laugh.

"What is it? Is there an epidemic of cholera there? Have gangsters taken hold of the place? Your policemen are so tough they can lift a bull by the horns. Surely they can restore order if there are any gangsters around. I say, ‘I would very much like to see Disneyland.' They say, ‘We cannot guarantee your security.' Then what must I do, commit suicide?"

Khrushchev was starting to look more angry than amused. His fist punched the air above his red face.

"That's the situation I find myself in," he said. "For me, such a situation is inconceivable. I cannot find words to explain this to my people."

The audience was baffled. Were they really watching the 65-year-old dictator of the world's largest country throw a temper tantrum because he couldn't go to Disneyland?

Sitting in the audience, Nina Khrushchev told David Niven that she really was disappointed that she couldn't see Disneyland. Hearing that, Sinatra, who was sitting next to Mrs. Khrushchev, leaned over and whispered in Niven's ear.

"Screw the cops!" Sinatra said. "Tell the old broad that you and I will take 'em down there this afternoon."

Before long, Khrushchev's tantrum—if that's what it was—faded away. He grumbled a bit about how he'd been stuffed into a sweltering limousine at the airport instead of a nice, cool convertible. Then he apologized, sort of: "You will say, perhaps, ‘What a difficult guest he is.' But I adhere to the Russian rule: ‘Eat the bread and salt but always speak your mind.' Please forgive me if I was somewhat hot-headed. But the temperature here contributes to this. Also"—he turned to Skouras—"my Greek friend warmed me up."

Relieved at the change of mood, the audience applauded. Skouras shook Khrushchev's hand and slapped him on the back and the two old, fat, bald men grinned while the stars, who recognized a good show when they saw one, rewarded them with a standing ovation.

The lunch over, Skouras led his new friend toward the soundstage where Can-Can was being filmed, stopping to greet various celebrities along the way. When Skouras spotted Marilyn Monroe in the crowd, he hastened to introduce her to the premier, who'd seen a huge close-up of her face—a clip from Some Like It Hot—in a film about American life at an American exhibition in Moscow. Now, Khrushchev shook her hand and looked her over.

"You're a very lovely young lady," he said, smiling.

Later, she would reveal what it was like to be eyeballed by the dictator: "He looked at me the way a man looks on a woman." At the time, she reacted to his stare by casually informing him that she was married.

"My husband, Arthur Miller, sends you his greeting," she replied. "There should be more of this kind of thing. It would help both our countries understand each other."

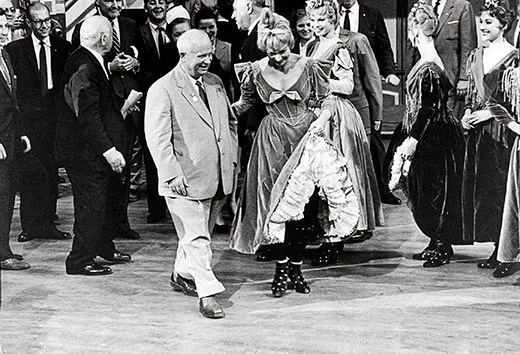

Skouras led Khrushchev and his family across the street to Sound Stage 8 and up a rickety wooden staircase to a box above the stage. Sinatra appeared onstage wearing a turn-of-the-century French suit—his costume. He played a French lawyer who falls in love with a dancer, played by Shirley MacLaine, who was arrested for performing a banned dance called the cancan. "This is a movie about a lot of pretty girls—and the fellows who like pretty girls," Sinatra announced.

Hearing a translation, Khrushchev grinned and applauded.

"Later in this picture, we go to a saloon," Sinatra continued. "A saloon is a place where you go to drink."

Khrushchev laughed at that, too. He seemed to be having a good time.

Shooting commenced; lines were delivered, and after a dance number that left no doubts why the cancan had once been banned, many spectators—American and Russian—wondered: Why did they choose this for Khrushchev?

"It was the worst choice imaginable," Wiley T. Buchanan, the State Department's chief of protocol, later recalled. "When the male dancer dived under [MacLaine's] skirt and emerged holding what seemed to be her red panties, the Americans in the audience gave an audible gasp of dismay, while the Russians sat in stolid, disapproving silence."

Later, Khrushchev would denounce the dance as pornographic exploitation, though at the time he seemed happy enough.

"I was watching him," said Richard Townsend Davies of the State Department, "and he seemed to be enjoying it."

Sergei Khrushchev, the premier's son, wasn't so sure. "Maybe father was interested, but then he started to think, What does this mean?" he recalled. "Because Skouras was very friendly, Father did not think it was some political provocation. But there was no explanation. It was just American life." Sergei shrugged, then added: "Maybe Khrushchev liked it, but I will say for sure: My mother did not like it."

A few moments later, Khrushchev slid into a long black limousine with huge tailfins. Lodge slipped in after him. The limo inched forward, slowly picking up speed. Having put the kibosh on Disneyland, Khrushchev's guides were compelled to come up with a new plan. They took the premier on a tour of tract housing developments instead.

Khrushchev never did get to Disneyland.

Peter Carlson spent 22 years at the Washington Post as a feature writer and columnist. He lives in Rockville, Maryland.

Adapted from K Blows Top, by Peter Carlson, published by PublicAffairs, a member of the Perseus Book Group. All rights reserved.