Nobody Walks in L.A.: The Rise of Cars and the Monorails That Never Were

As strange as it may seem today, the automobile was seen by many as the progressive solution to the transportation problems of Los Angeles

![]()

Artist’s conception of a future monorail for Los Angeles, California in 1954 (Source: Novak Archive)

“Who needs a car in L.A.? We got the best public transportation system in the world!” says private detective Eddie Valiant in the 1988 film Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

Set in 1947, Eddie is a car-less Angeleno and the movie tells the tale of a an evil corporation buying up the city’s streetcars in its greedy quest to force people out of public transit and into private automobiles. Eddie Valiant’s line was a wink at audiences in 1988 who knew quite well that public transportation was now little more than a punchline.

Aside from Detroit there’s no American city more identified with the automobile than Los Angeles. In the 20th century, the Motor City rose to prominence as the home of the Big Three automakers, but the City of Angels is known to outsiders and locals alike for its confusing mess of freeways and cars that crisscross the city — or perhaps as writer Dorothy Parker put it, crisscross the “72 suburbs in search of a city.”

Los Angeles is notorious for being hostile to pedestrians. I know plenty of Angelenos who couldn’t in their wildest dreams imagine navigating America’s second largest city without a car. But I’ve spent the past year doing just that.

About a year and a half ago I went down to the parking garage underneath my apartment building and found that my car wouldn’t start. One thing I learned when I moved to Los Angeles in 2010 was that a one-bedroom apartment doesn’t come with a refrigerator, but it does come with a parking space. “We only provide the essentials,” my apartment’s building manager explained to me when I asked about this regional quirk of the apartment rental market. Essentials, indeed.

My car (a silver 1998 Honda Accord with tiny pockets of rust from the years it survived harsh Minnesota winters) probably just had a problem with its battery, but I really don’t know. A strange mixture of laziness, inertia, curiosity and dwindling funds led me to wonder how I might get around the city without wheels. A similar non-ideological adventure began when I was 18 and thought “I wonder how long I can go without eating meat?” (The answer was apparently two years.)

Living in L.A. without a car has been an interesting experiment; one where I no longer worry about fluctuations in the price of gas but sometimes shirk social functions because getting on the bus or train doesn’t appeal to me on a given day. It’s been an experiment where I wonder how best to stock up on earthquake disaster supplies (I just ordered them online) and how to get to Pasadena to interview scientists at JPL (I just broke down and rented a car for the day). The car — my car — has been sitting in that parking spot for over a year now, and for the most part it’s worked out pretty well.

But how did Los Angeles become so automobile-centric? How did Angeleno culture evolve (or is it devolve?) to the point where not having a car is seen as such a strange thing?

One of the first cars ever built in Los Angeles, made in 1897 by 17-year-old Earle C. Anthony (Photo by Matt Novak at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles)

Los Angeles owes its existence as a modern metropolis to the railroad. When California became a state in 1850, Los Angeles was just a small frontier town of about 4,000 people dwarfed by the much larger Californian cities of San Francisco and Sacramento. Plagued by crime, some accounts claimed that L.A. suffered a murder a day in 1854. But this tiny violent town, referred to as Los Diablos (the devils) by some people in the 1850s would become a boomtown ready for a growth explosion by the 1870s.

From the arrival of the transcontinental railroad in 1876 until the late 1920s, the City of Angels experienced incredibly rapid population growth. And this growth was no accident. The L.A. Chamber of Commerce, along with the railroad companies, aggressively marketed the city as one of paradise — a place where all your hopes and dreams could come true. In the late 19th century Los Angeles was thought to be the land of the “accessible dream” as Tom Zimmerman explains in his book Paradise Promoted.

Los Angeles was advertised as the luxurious city of the future; a land of both snow-capped mountains and beautiful orange groves — where the air was clean, the food was plentiful and the lifestyle was civilized. In the 1880s, the methods of attracting new people to the city involved elaborate and colorful ad campaigns by the railroads. And people arrived in trains stuffed to capacity.

With the arrival of the automobile in the late 1890s the City of Angels began experimenting with the machine that would dramatically influence the city’s landscape. The first practical electric streetcars were started in the late 1880s, replacing the rather primitive horse-drawn railways of the 1870s. The mass transit system was actually borne of real estate developers who built lines to not only provide long term access to their land, but also in the very immediate sense to sell that land to prospective buyers.

By the 1910s there were two major transit players left: The Los Angeles Streetway streetcar company (LARY and often known as the Yellow Cars) and the Pacific Electric Railway (PE and often known simply as the Red Cars).

No one would mistake Who Framed Roger Rabbit? for a documentary, but the film has done a lot to cement a particular piece of L.A. mythology into the popular imagination. Namely, that it was the major car companies who would directly put the public transit companies out of business when they “purchased” them in the 1940s and shut them down. In reality, the death of L.A.’s privately-owned mass transit would be foreshadowed in the 1910s and would be all but certain by the end of the 1920s.

By the 1910s the streetcars were already suffering from widespread public dissatisfaction. The lines were seen as increasingly undependable and riders complained about crowded trains. Some of the streetcar’s problems were a result of the automobile crowding them out in the 1910s, congesting the roads and often causing accidents that made service unreliable. Separating the traffic of the autos, pedestrians and streetcars were seen as a priority that would not be realized until the late 20th century. As Scott L. Bottles notes in his book Los Angeles and the Automobile, “As early as 1915, called for plans to separate these trains from regular street traffic with elevated or subway lines.”

The recession-plagued year 1914 saw the explosive rise of the “jitney,” an unlicensed taxi that took passengers for just a nickel. The private streetcar companies refused to improve their service in a time of recession and as a result drove more and more people to alternatives like the jitney and buying their own vehicle.

The Federal Road Act of 1916 would jumpstart the nation’s funding of road construction and maintenance, providing matching funding to states. But it was the Roaring Twenties that would set Los Angeles on an irreversible path as a city dominated by the automobile. L.A.’s population of about 600,000 at the start of the 1920s more than doubled during the decade. The city’s cars would see an even greater increase, from 161,846 cars registered in L.A. County in 1920 to 806,264 registered in 1930. In 1920 Los Angeles had about 170 gas stations. By 1930 there were over 1,500.

This early and rapid adoption of the automobile in the region is the reason that L.A. was such a pioneer in the area of automotive-centric retailing. The car of the 1920s changed the way that people interacted with the city and how it purchased goods, for better and for worse. As Richard Longstreth notes in his 2000 book, The Drive-In, The Supermarket, and the Transformation of Commercials Space in Los Angeles, the fact that Southern California was the “primary spawning ground for the super service station, the drive-in market, and the supermarket” was no coincidence. Continuing the trend of the preceding decades, the population of Los Angeles swelled tremendously in the 1910s and ’20s, with people arriving by the thousands.

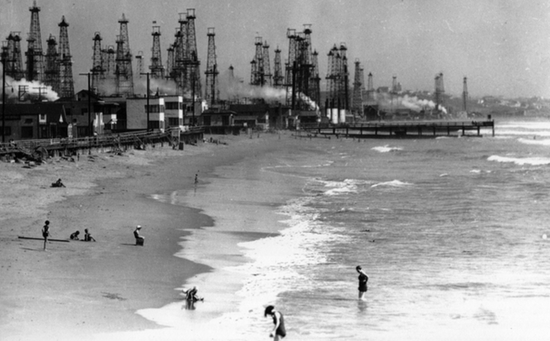

“This burgeoning middle class created one of the highest incidences of automobile ownership in the nation, and both the diffuse nature of the settlement and a mild climate year-round yielded an equally high rate of automobile use,” Longstreth explains. The city, unencumbered by the geographic restrictions of places like San Francisco and Manhattan quickly grew outward rather than upward; fueled by the car and quite literally fueled by the many oil fields right in the city’s backyard. Just over the hills that I can see from my apartment building lie oil derricks. Strange metal robots in the middle of L.A. dotting the landscape, bobbing for that black gold to which we’ve grown so addicted.

Oil wells at Venice Beach on January 26, 1931 (Source: Paradise Promoted by Tom Zimmerman)

Los Angeles would see and turn down many proposals for expanded public transit during the first half of the 20th century. In 1926 the Pacific Electric built a short-running subway in the city but it did little to fix the congestion problems that were happening above ground.

In 1926 there was a big push to build over 50 miles of elevated railway in Los Angeles. The city’s low density made many skeptical that Los Angeles could ever support public transit solutions to its transportation woes in the 20th century. The local newspapers campaigned heavily against elevated railways downtown, even going so far as to send reporters to Chicago and Boston to get quotes critical of those cities’ elevated railways. L.A.’s low density was a direct result of the city’s most drastic growth occurring in the 1910s and ‘20s when automobiles were allowing people to spread out and build homes in far flung suburbs and not be tied to public transit to reach the commercial and retail hub of downtown.

As strange as it may seem today, the automobile was seen by many as the progressive solution to the transportation problems of Los Angeles in the 1920s. The privately owned rail companies were inflating their costs and making it impossible for the city to buy them out. Angelenos were reluctant to to subsidize private rail, despite their gripes with service. Meanwhile, both the city and the state continued to invest heavily in freeways. In 1936 Fortune magazine reported on what they called rail’s obsolescence.

Though the city’s growth stalled somewhat during the Great Depression it picked right back up again during World War II. People were again moving to the city in droves looking for work in this artificial port town that was fueling the war effort on the west coast. But at the end of the war the prospects for mass transit in L.A. were looking as grim as ever.

In 1951 the California assembly passed an act that established the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority. The Metro Transit Authority proposed a monorail between the San Fernando Valley and downtown Los Angeles. A 1954 report issued to the Transit Authority acknowledged the unique challenges of the region, citing its low density, high degree of car ownership and current lack of any non-bus mass rapid transit in the area as major hurdles.

The July 1954 issue of Fortune magazine saw postwar expansion brought on by the car as an almost insurmountable challenge for the urban planner of the future:

As a generation of city and regional planners can attest, it is no simple matter to draw up a transit system that will meet modern needs. In fact, some transportation experts are almost ready to concede that the decentralization of urban life, brought about by the automobile, has progressed so far that it may be impossible for any U.S. city to build a self-supporting rapid-transit system. At the same time, it is easy to show that highways are highly inefficient for moving masses of people into and out of existing business and industrial centers.

Somewhat interestingly, that 1954 proposal to the L.A. Metro Transit Authority called their monorail prescription “a proper beginning of mass rapid transit throughout Los Angeles County.” It was as if the past five decades had been forgotten.

Longtime Los Angeles resident Ray Bradbury never drove a car. Not even once. When I asked him why, he said that he thought he’d “be a maniac” behind the wheel. A year ago this month I walked to his house which was about a mile north of my apartment (uphill) and arrived dripping in sweat. Bradbury was a big proponent of establishing monorail lines in Los Angeles. But as Bradbury wrote in a 2006 opinion piece in the Los Angeles Times, he believed the Metro line from downtown to Santa Monica (which now stretches to Culver City and is currently being built to reach Santa Monica) was a bad idea. He believed that his 1960s effort to promote monorails in Los Angeles made a lot more sense financially.

Bradbury said of his 1963 campaign, “During the following 12 months I lectured in almost every major area of L.A., at open forums and libraries, to tell people about the promise of the monorail. But at the end of that year nothing was done.” Bradbury’s argument was that the taxpayers shouldn’t have to foot the bill for transportation in their city.

With the continued investment in highways and the public repeatedly voting down funding for subways and elevated railways at almost every turn (including our most recent ballot’s Measure J which would have extended a sales tax increase in Los Angeles County to be earmarked for public transportation construction) it’s hard to argue that anyone but the state of California, the city of Los Angeles, and the voting public are responsible for the automobile-centric state of the city.

But admittedly the new Metro stop in Culver City has changed my life. Opened in June of last year, it has completely transformed the way that I interact with my environment. While I still may walk as far as Hollywood on occasion (about 8 miles), I’m able to get downtown in about 25 minutes. And from Downtown to Hollywood in about the same amount of time.

Today, the streetcars may be returning to downtown L.A. with construction starting as early as 2014 pending quite a few more hurdles. Funding has nearly been secured for the project which would again put streetcars downtown by 2016.

But even with all of L.A.’s progress in mass transit, my car-less experiment will probably come to a close this year. Life is just easier with a car in a city that still has a long way to go in order to make places like Santa Monica, Venice, the Valley and (perhaps most crucially for major cities trying to attract businesses and promote tourism) the airport accessible by train.

But until then my car will remain parked downstairs. I’ll continue to walk almost everywhere, and you can be sure I’ll dream of the L.A. monorails that never were.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)