At the age of 78, a frail Jefferson Davis journeyed back to Montgomery, Alabama, where he had first been sworn in as president of the Confederacy a quarter-century earlier. There, greeted by an “ovation…said never to have been equaled or eclipsed in that city,” the once-unpopular Davis helped lay the cornerstone for a monument to the Confederate dead. Despite failing health, he then embarked on a final speaking tour in the spring of 1886 to Atlanta and on to Savannah—ironically retracing General Sherman’s march through Georgia, which had crushed and humiliated the South and brought the Civil War closer to an end.

“Is it a lost cause now?” Davis defiantly thundered to the adoring, all-white crowds who set off fireworks and artillery salutes in his honor. He provided his own answer, shouting: “Never.”

Clearly, much had changed since Davis had ignominiously tried escaping Union pursuers by disguising himself in his wife’s raincoat. For this masquerade, he had been mercilessly lampooned in Northern caricature as a coward in drag—portrayed in hoopskirts and a ludicrous bonnet. Yet now, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, one of the New York weeklies that had mocked Davis in 1865, marveled at his comeback.

The paper was not alone in this about-face.

As the South rewrote the history of the war and reaffirmed a white supremacist ideology, the North’s printmakers, publishers and image makers operated right beside them. Reaping financial windfalls, these firms helped propagate what’s known as the “Lost Cause” phenomenon through sympathetic mass-marketed prints designed for homes, offices, and veterans’ clubs throughout the former Confederacy. Most critically to the modern era, these images also helped fund the erection of statues that are only now beginning to be removed from public squares.

Printmaking was a lucrative industry in the late-19th century. Publishers (Currier & Ives is probably the best-known) sold mass-produced separate-sheet pictures by the thousands to wholesalers, in retail shops, through news dealers and other sub-retailers and via mail to distributors and individuals. Lithographs from a printmaker could cost as little as ten cents; engravings five to ten dollars—depending on size—though one oversized Lincoln deathbed engraving went for $50 for signed artist’s proofs.

In addition to being profitable, these images were ubiquitous. Home decorating books and magazines of the time made clear that framed artworks testifying to patriotic and political impulses were crucial additions to the American home.

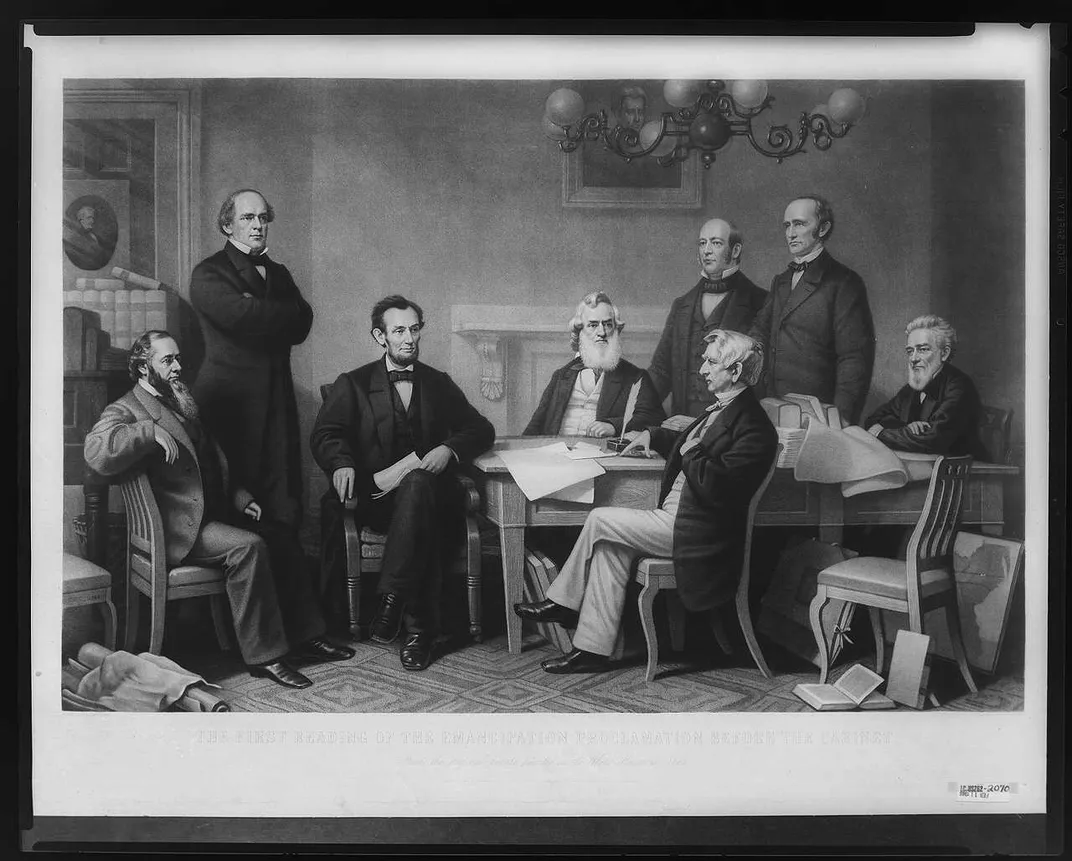

Historians believe, based on an 1890s New York Times story, that a New York-issued print of the first reading of the Emancipation Proclamation sold some 100,000 copies over 30 years; it was the big best-seller of its day. But not all New York image-makers confined their attention to pro-Union and anti-slavery themes

***********

Most print-publishing firms took hold in the North, where German-born lithographers had tended to congregate after immigrating to the U.S. By 1861, opportunities for profit seemed especially rich when their smaller, Southern-based competitors verged on collapse due to manpower shortages and blockade-driven shortfalls in supplies. But early in the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation forbidding “all commercial intercourse” between U.S. citizens and insurrectionists in the seceded states, leaving the industry in the lurch.

The executive order halted the efforts of New York-based image-makers like Jones & Clark, who had quickly issued handsome images of Confederates like Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis, and C. F. May, who had rushed out a group portrait of 49 Officers of the C. S. Army & Navy. The two shops were apparently had no concerns that such uncritical depictions of Confederate celebrities might amount to treason.

Once the Southern market reopened with the end of the war, Northern engravers and lithographers unapologetically rushed back into a business that quickly included supplying icons of, and for, the former enemy. And importantly, some of these images were specifically commissioned to raise monies to erect the monuments and statues that have emerged at the center of the new re-evaluation of Confederate memorials.

For example, when Lee admirers at the former Washington College in Lexington, Virginia—where Lee had served as postwar president and which now bore his name—decided to commission a recumbent statue to adorn his tomb, Washington and Lee turned to a Manhattan publisher to facilitate fundraising. To accommodate this new client, New York-based portrait engraver Adam B. Walter and his publisher, Bradley & Co. copied a wartime portrait photograph of the general and in 1870 issued a 17-by-14-inch engraved copy whose caption unambiguously announced its intention: “Sold by authority of the Lee Memorial Association for the erection of a Monument at the tomb of Genl. R. E. Lee at the Washington & Lee University, Lexington, Va.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3b/b6/3bb6129b-3d9d-4f6e-8bdf-e2e6ff96d3c8/02992v_loc_lee_portrait.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/b7/eab70429-e22b-4d4f-9e9c-a08bf3ca41a5/stonewalljackson2_loc.jpg)

When fundraising lagged, the New York printmakers were asked to produce a companion print of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston to attract additional subscribers. Not surprisingly, when the Virginia Military Institute, with a campus adjacent to that of Washington and Lee, decided to erect a statue of its own to honor Jackson, Lee’s lieutenant and a Lexington resident, Bradley & Co. obliged with yet another fundraising print. Its caption similarly declared, “for the purpose of erecting a Monument in the memory of Genl. Thomas J. Jackson.”

Perhaps the biggest, in the literal and the figurative sense, Confederate monument under scrutiny today honors Lee and stands at the head of a profession of monuments along Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia. Governor Ralph Northam is pursuing the statue’s removal in the courts, and several other former occupants of Monument Row have already been removed (Jackson and Mathew Fontaine Maury by order of the mayor, and Jefferson Davis by a crowd of demonstrators). The Lee equestrian, too, might never have been built without the effort of printmakers: this time a Baltimore lithography firm supplied a popular portrait of Lee astride his horse, Traveler, as a fundraising premium. Of course, Baltimore cannot be called a Northern city like New York (although secessionist sympathy remained strong for a time in the latter). But the border state of Maryland had remained in the Union, abolished slavery and voted Republican in 1864, more than a year before the 13th Amendment outlawed the institution nationwide.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a0/3e/a03e02c5-8450-4668-ae30-0a443c166ab0/07096r_loc_genl_lee_on_traveler.jpg)

The shop responsible for the picture, run by Marylander August Hoen and his family, had been shut down by the U.S. army during the first year of the war for the sin of publishing pro-Confederate images. Now, more than a decade later, they seized the chance to recoup their losses. More than a keepsake, Hoen’s 1876 print was issued to raise funds for the Lee Monument Association in Richmond. The group offered Genl. Lee on Traveler to “any college, school, lodge, club, military or civic association” that sent $10 for the statue fund. As an orator declared at the statue’s 1890 dedication, “A grateful people” gave “of their poverty gladly, that…future generations may see the counterfeit presentment of this man, this ideal and bright consummate flower of our civilization.”

Monument associations seeking to finance statues of Jackson and Davis also relied on Northern image-makers to supply souvenirs in exchange for donations. The resulting pictures not only fueled the monument craze in the former Confederacy, they reached a status akin to religious icons adorning the walls of Southern parlors.

The images may also have achieved a degree of acceptance among supporters of sectional reconciliation in the North. While the irreconcilable abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison viewed Lee’s postwar college presidency as an outrage—the thought made him wonder whether Satan had “regained his position in heaven”— pro-Democratic (and racist) newspapers like the New York Herald began touting Lee as “a greater man” than the Union generals who had defeated him. His admirers in Poughkeepsie, New York, of all bastions of Lost Cause sentiment, founded a Lee Society.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/d8/70d83461-ccae-4598-9c94-0883e8cac76e/stonewall_jackson_family_sartain_metmuseum.jpg)

Even those firms without contracts with monument associations recognized the profit to be made from lionizing onetime enemy combatants. Philadelphia engraver William Sartain, for one, came out with a flattering mezzotint of Jackson along with a group portrait of Jackson and his family, seated in a parlor decorated by statuettes of George Washington and John C. Calhoun. (Appealing to all tastes, Sartain produced a similar print of Lincoln and his family.) J. C. Buttre of New York contributed Prayer in “Stonewall” Jackson’s Camp, a tribute to the ferocious general’s spiritual side.

In Chicago, Kurz & Allison issued a lithograph of Jefferson Davis and Family, an obvious attempt to soften Davis’ flinty image by showing him alongside his wife and children. Haasis & Lubrecht, another New York lithography firm, had previously published a postwar 1865 print depicting Lincoln surrounded by Union officers killed in the war, entitled Our Fallen Heroes. The publisher apparently saw no reason not to use the identical design two years later to produce Our Fallen Braves, featuring a central portrait of Stonewall Jackson surrounded by dead Confederates.

As for Currier & Ives, that powerhouse firm had always eschewed political favoritism in quest of profits from the widest possible customer base. In 1860, and again in 1864, they had provided posters touting the presidential candidacy of Republican Abraham Lincoln, but, for those who opposed him, similarly designed broadsides celebrating his Democratic opponents.

After the war, they outdid themselves with works directed to audiences in the former Confederacy. One example was The Death of “Stonewall” Jackson, which treated the general’s passing as tenderly as the firm had envisioned the death of Lincoln. But the most emblematic—and audacious—was Currier & Ives’ lithograph of a Confederate veteran returning to his ruined homestead, there to discover the graves of the family members he had left behind, one surmises, to die in deprivation. As the soldier weeps into his handkerchief, a cross rises in the sky above the treetops in the shape of the emblematic stars and bars of the Confederacy. Appropriately, the print was bluntly titled The Lost Cause. Not long afterward, Currier & Ives began issuing a “comic” series of what it called Darktown prints, cruelly stereotyping African Americans as ignorant, shiftless buffoons unable to cope with their newfound freedom, much less their legal equality. These became best-sellers.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/da/3e/da3e6344-c82b-473b-bf0a-6c65adf27083/09370v.jpg)

The lines separating memory from myth had blurred unrecognizably. As late as 1890, the same year the Lee statue was dedicated in Richmond, I. S. Johnson & Co. published a tinted lithograph of the recently deceased Jefferson Davis, showing him with a white beard so full, and a jaw so square, that the once-wizened figure seemed to morph into a carbon copy of Lee himself. That image was produced in Boston. For its analogue, see Robert Edward Lee 1807-1870, an engraved portrait positioned above a Lee family crest and motto “Ne Incautus Futuri—Be Not Unmindful of the Future,” between the flags of the Confederacy. Though issued as a giveaway for the Confederate Memorial Literary Society, it was produced by the John A. Lowell Bank Note Company, also Boston-based.

As Northerners today join many Southerners in demanding the removal of statues and monuments that have too long dominated public squares in the old Confederacy, it might be time as well to concede that Northern commercial interests were complicit in building them in the first place—generating celebratory images meant not only to finance public statues, but, as a bonus, to occupy sacred space in private homes. The Lost Cause may have been given voice by Jefferson Davis on his final speaking tour, but it was given visual form by image-makers in the states against which he had once rebelled.

Harold Holzer, winner of the National Humanities Medal and the Lincoln Prize, is the co-author—with Mark E. Neely, Jr. and Gabor Boritt—of the 1987 book, The Confederate Image: Prints of the Lost Cause.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a0/64/a0642caa-88aa-4a57-9b23-3ffddcdf6a25/lost_cause_mobile.png)

:focal(961x323:962x324)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/36/f8/36f8a0a7-95c6-48c0-97f6-85bb7b0a3d9c/lost_cause_longform.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/harold2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/harold2.png)