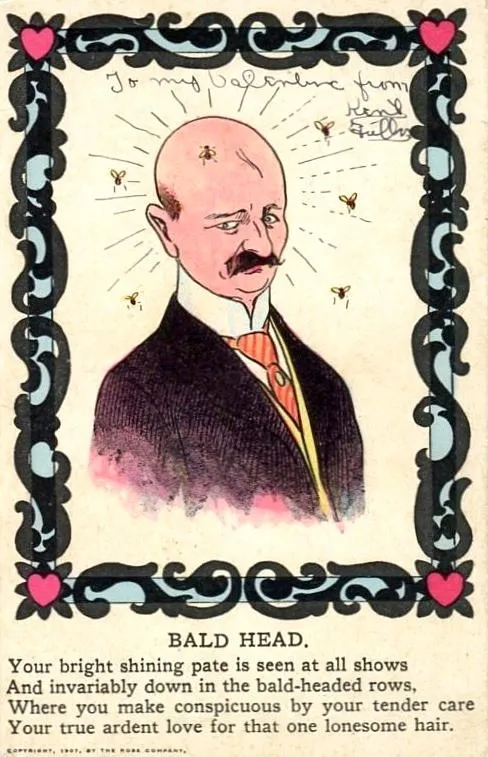

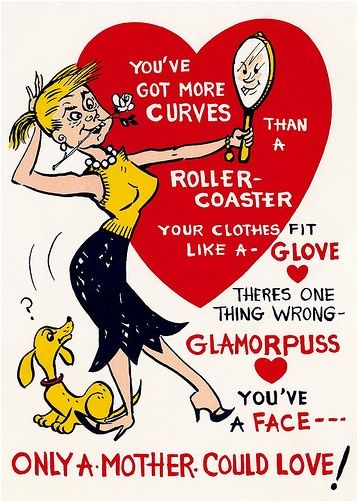

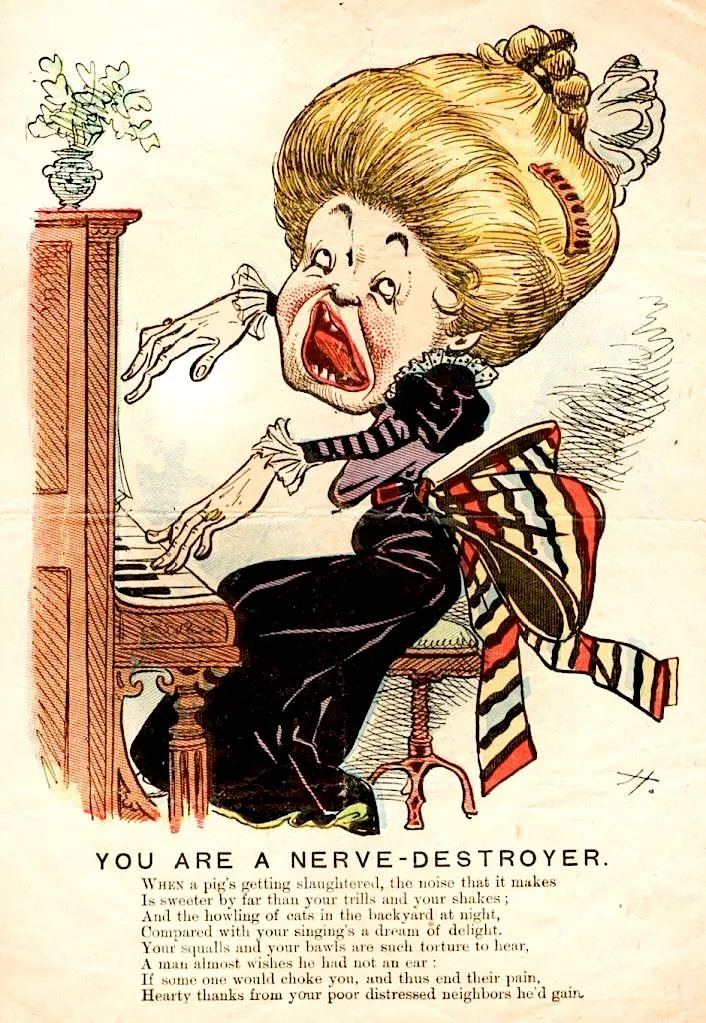

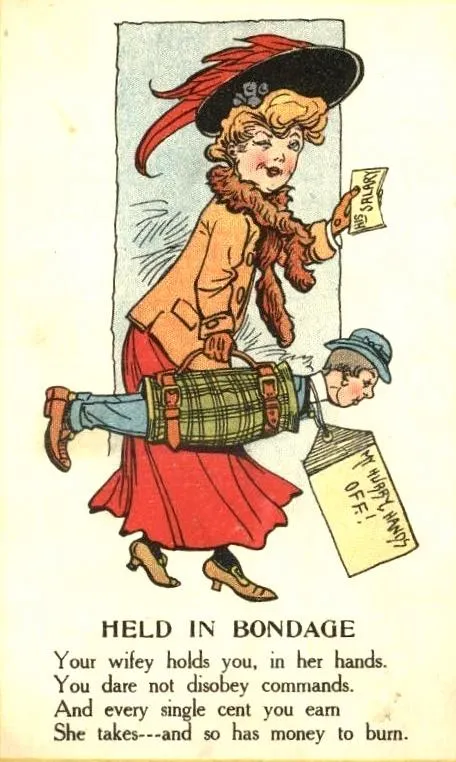

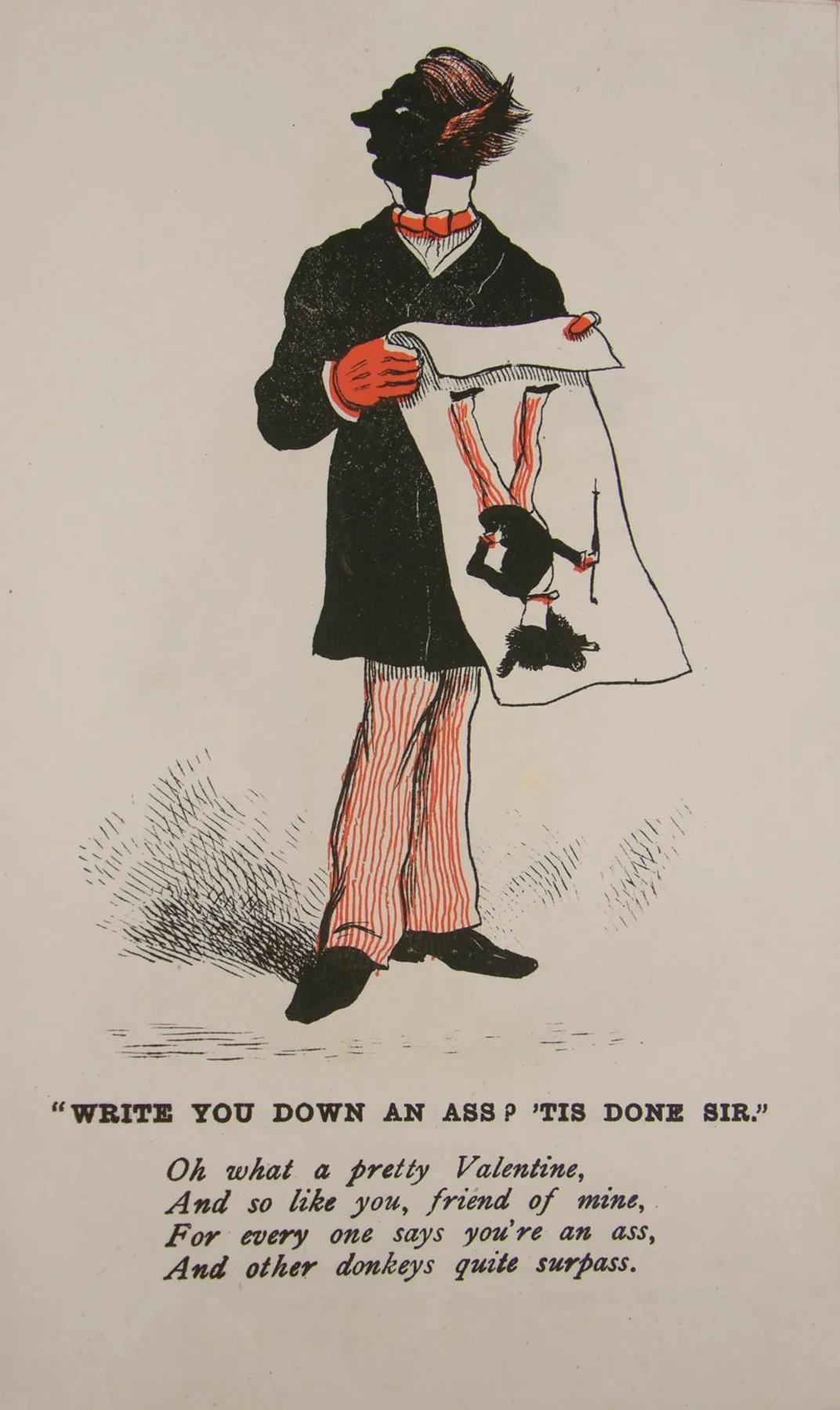

Nothing Says ‘I Hate You’ Like a ‘Vinegar Valentine’

For at least a century, Valentine’s Day was used as an excuse to send mean, insulting cards

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/7d/237dcae0-d60e-4f40-bd88-981954bc99f3/loverboy-wr.jpg)

Valentine’s Day is known as a time for people to send love notes, including anonymous ones signed “your secret admirer.” But during the Victorian era and the early 20th century, February 14 was also a day on which unlucky victims could receive “vinegar valentines” from their secret haters.

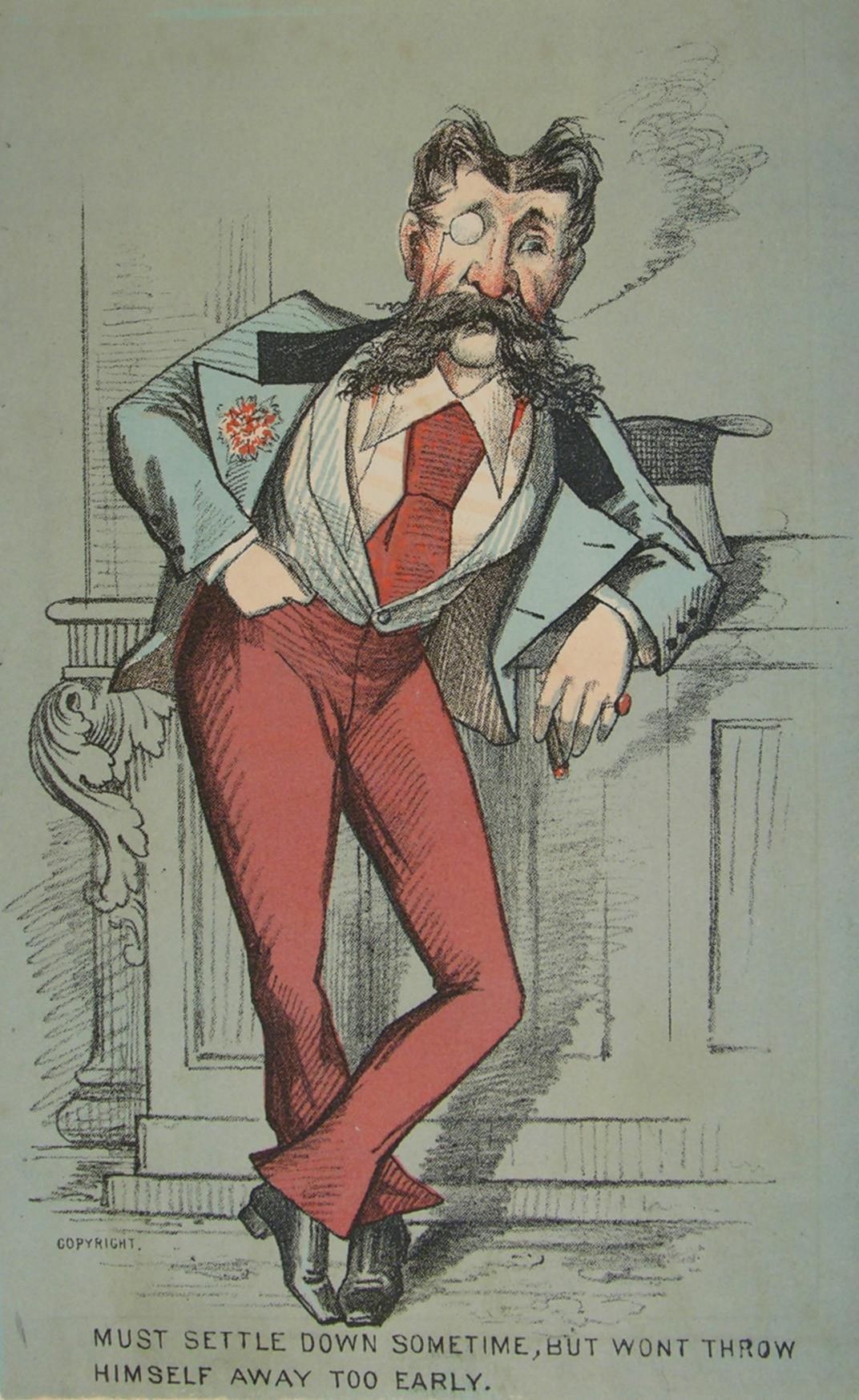

Sold in the United States and Britain, these cards featured an illustration and a short line or poem that, rather than offering messages of love and affection, insulted the recipient. They were used as an anonymous medium for saying mean things that its senders wouldn’t dare say to someone’s face—a concept that may sound familiar to today’s readers. Scholar Annebella Pollen, who has written an academic paper on vinegar valentines, says that people often ask her whether these cards were an early form of “trolling.”

“We like to think that we’re living in these terrible times,” she says. “But actually if you look at intimate history, things weren’t always so rosy.”

People sent vinegar valentines as far back as at least 1840. Back then, they were called “mocking,” “insulting,” or “comic” valentines—“vinegar” seems to be a modern description. They were especially popular during the mid-19th century, when both the U.S. and Britain caught Valentine’s Day fever, a time talked about as “a Valentine’s craze or Valentine’s mania,” Pollen says. “The press was always talking about this phenomena … These were new, kind of mind-boggling quantities, these millions and millions of cards,” both sweet and sour.

Printers mass-produced Valentine cards that ranged from the expensive, ornate, and sentimental kind to the vinegar variety, which were cheap. “They were designed to expand this holiday into something that could include a whole range of different people and a whole range of different emotions,” she says.

Before these mass-produced cards hit the market, people had hand made their own valentines, both sentimental and vinegar (so far, the historical examples of nicer valentines predate the meaner ones). Pollen argues that although manufacturers didn’t invent vinegar valentines, they expanded upon them. In Barry Shank’s book on greeting cards and American business culture, he writes that vinegar valentines “were a part of the valentine craze from the earliest years of its commercialization.”

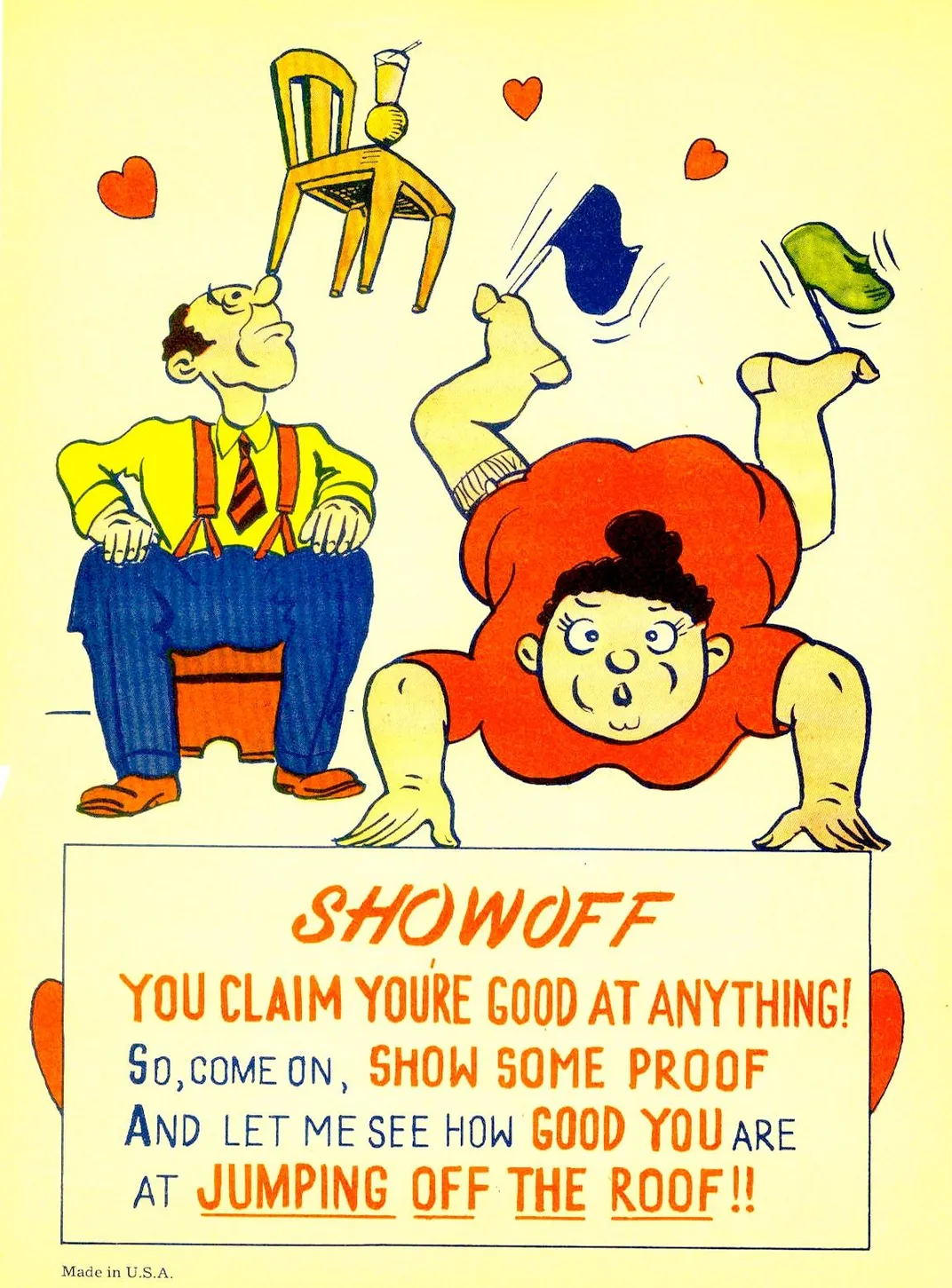

Vinegar valentines could be lightly teasing or truly nasty—such as those that suggested the reader commit suicide. And many of them were written as though these negative thoughts were popular opinion. One, for example, told the reader that “Everyone thinks you an ignorant lout.”

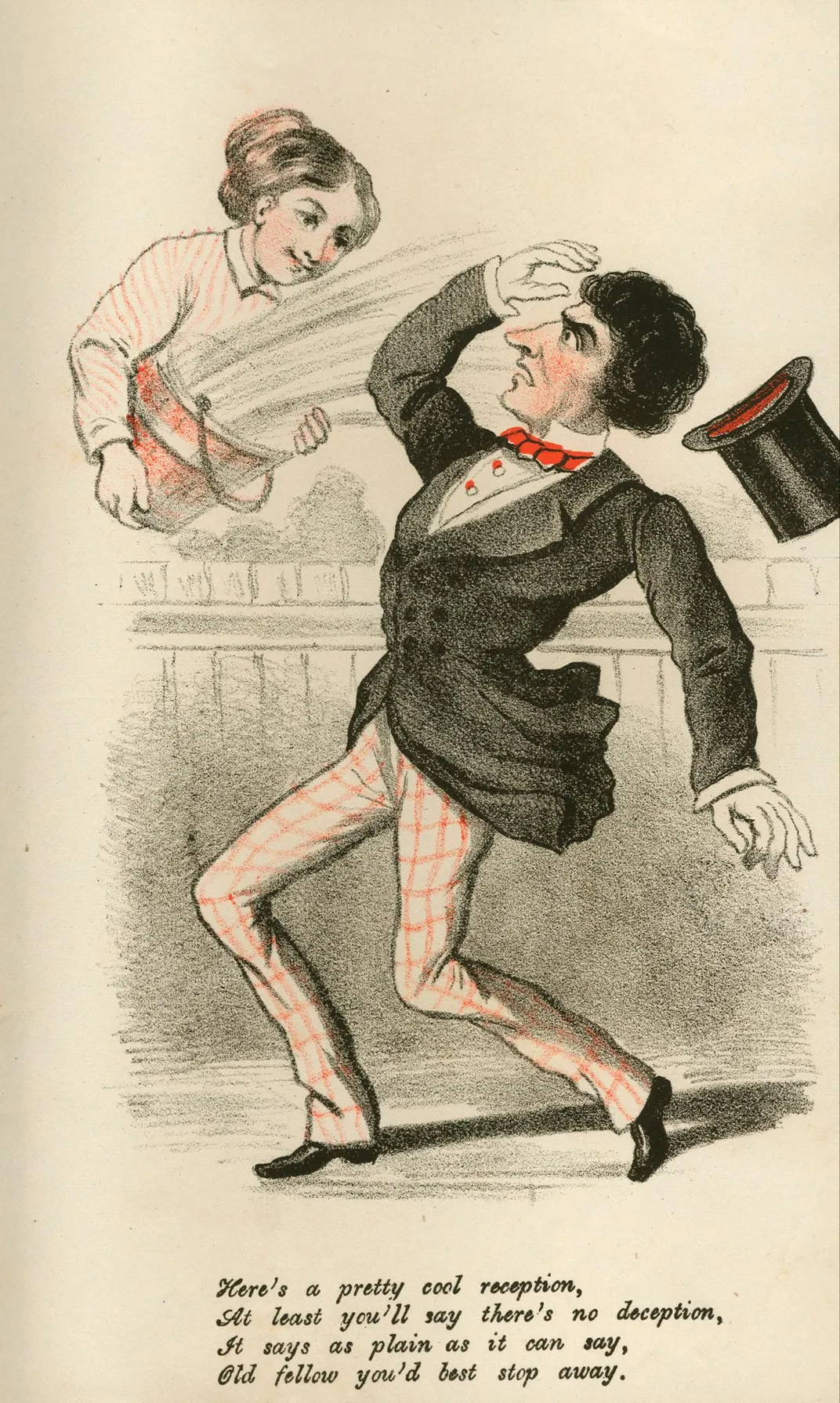

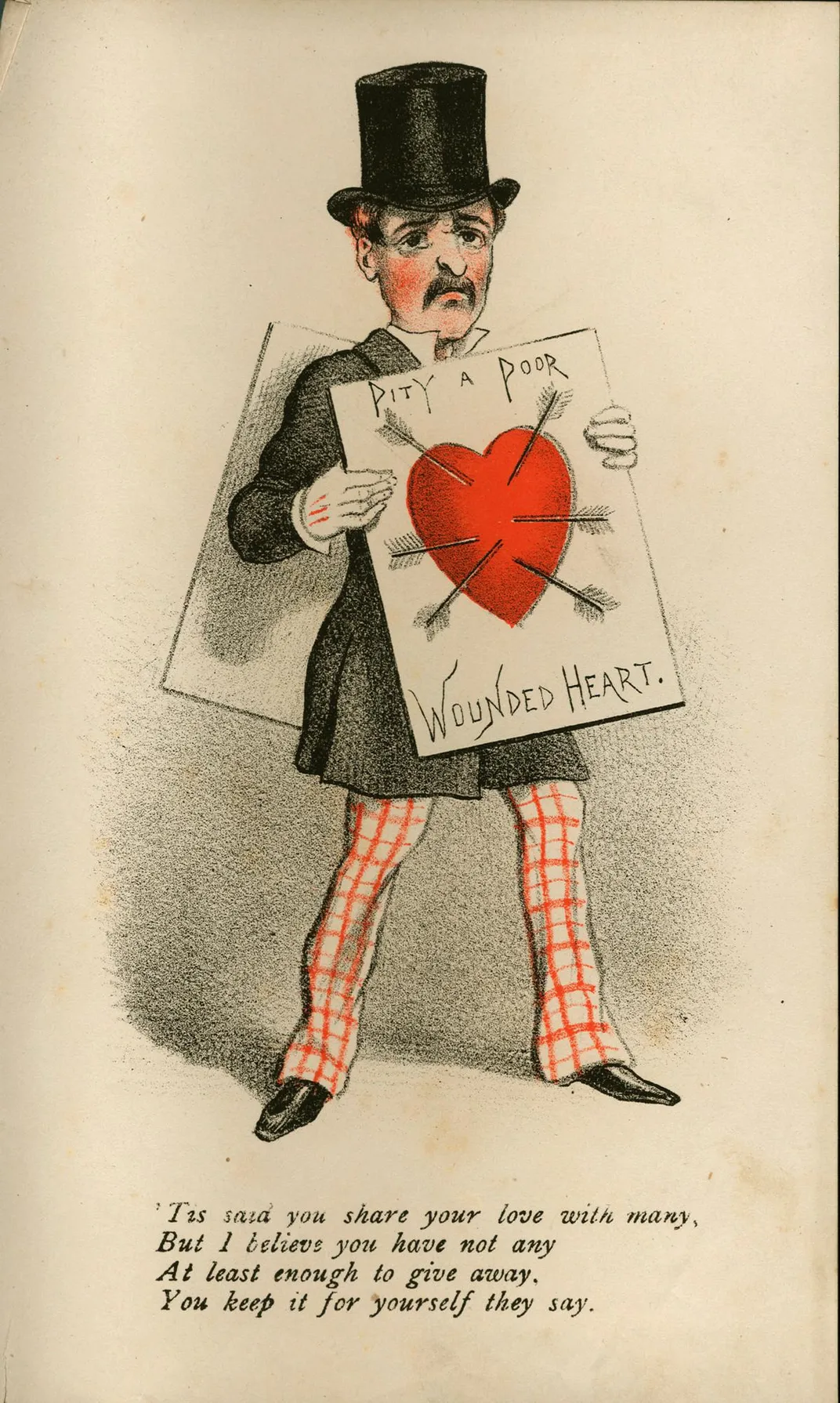

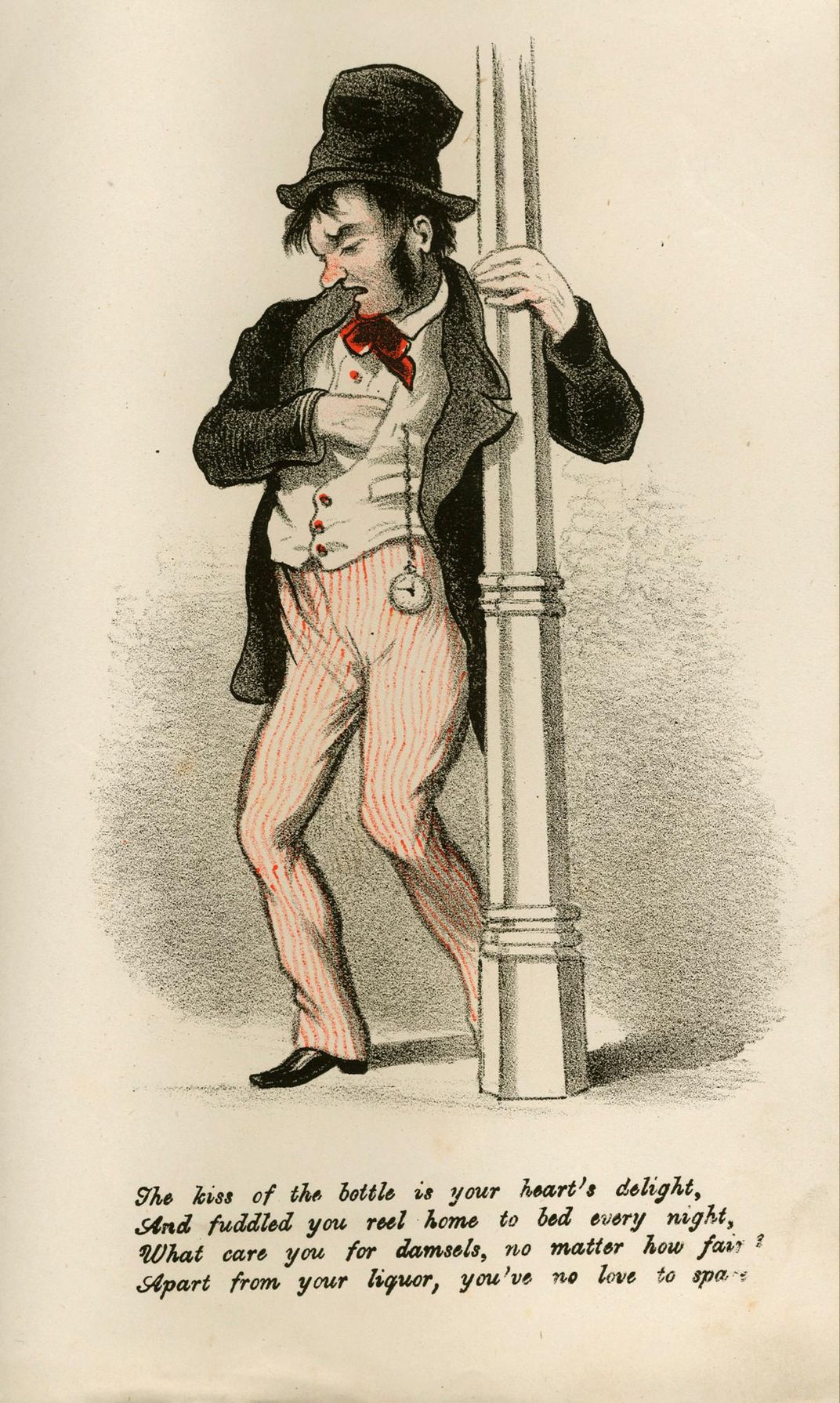

Some warded off unwanted suitors, while others made fun of people for drinking too much, putting on airs, or engaging in excessive public displays of affection. There were cards telling women they were too aggressive or accusing men of being too submissive, and cards that insulted any profession you could think of—artist, surgeon, saleslady, etc.

So specialized were these cards, particularly those sold in the U.S., Shank writes, that they actually “documented the changing shape of the middle classes.” Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, their subjects shifted “from sailor, carpenter, and tailor to policeman, clerk, and secretary.”

And who could blame them? Just as card makers today sell valentines targeted for siblings, in-laws, grandparents, or pets, manufacturers during Valentine’s Day’s heyday saw these insulting messages as a way to make money, and it’s clear that consumers liked what they were selling. According to the writer Ruth Webb Lee, by the mid-19th century, vinegar valentines represented about half of all valentine sales in the U.S.

Yet not everyone was a fan of these mean valentines. In 1857, The Newcastle Weekly Courant complained that “the stationers’ shop windows are full, not of pretty love-tokens, but of vile, ugly, misshapen caricatures of men and women, designed for the special benefit of those who by some chance render themselves unpopular in the humbler circles of life.”

Although scholars don’t know how many of them were sent as a joke—the someecards of their day—or how many were meant to harm, it is clear that some people took their message seriously. In 1885, London’s Pall Mall Gazette reported that a husband shot his estranged wife in the neck after receiving a vinegar valentine that he could tell was from her. Pollen also says there was a report of someone committing suicide after receiving an insulting valentine—not completely surprising, considering that’s exactly what some of them suggested.

“We see on Twitter and on other kinds of social media platforms what happens when people are allowed to say what they like without fear of retribution,” she says. “Anonymous forms [of communication] do facilitate particular kinds of behavior. They don’t create them, but they create opportunities.”

Compared to other period cards, there aren’t very many surviving specimens of vinegar valentines. Pollen attributes this to the fact that people probably didn’t save nasty cards that they got in the mail. They were more likely to preserve sentimental valentines like the ones people exchange today.

These cards are a good reminder that no matter how much people complain that the holiday makes them feel either too pressured to buy the perfect gift or too sad about being single, it could be worse. You could get a message about how everyone thinks you’re an ass.