Editor’s Note, September 24, 2019:The full English-language version of Renia Spiegel’s diary was published today. We wrote about her family’s rediscovery of the journal in our November 2018 issue. You can read our exclusive excerpt of Renia's diary here.

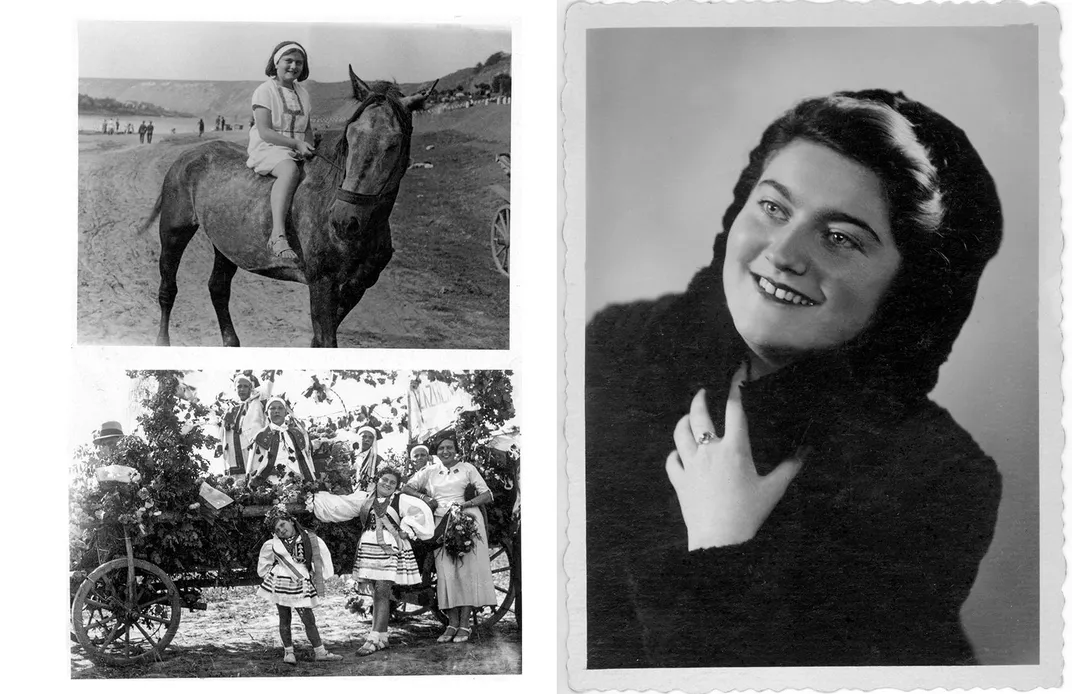

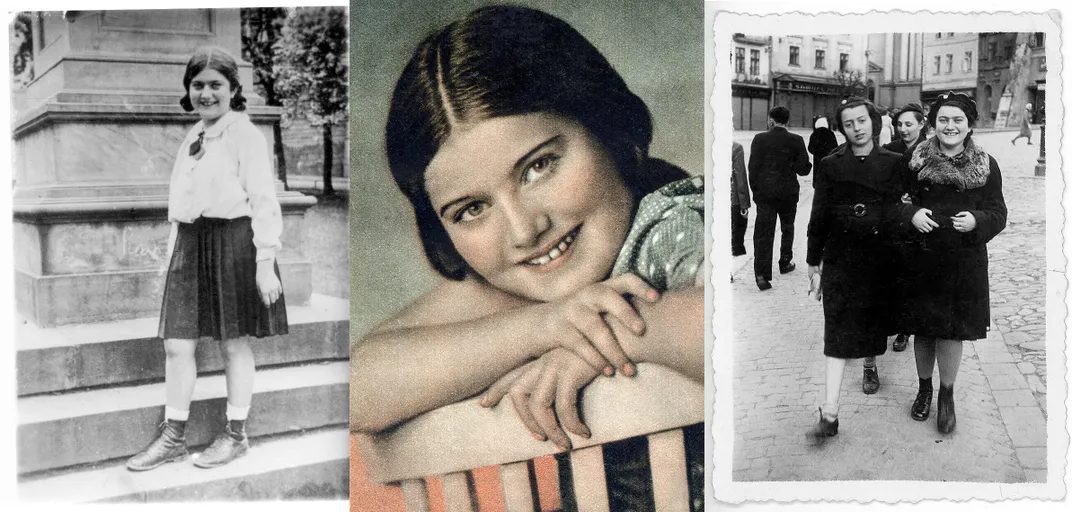

On January 31, 1939, a 15-year-old Jewish girl sat down with a school notebook in a cramped apartment in a provincial town in Poland and began writing about her life. She missed her mother, who lived far away in Warsaw. She missed her father, who was ensconced on the farm where her family once lived. She missed that home, where she had spent the happiest days of her life.

The girl’s name was Renia Spiegel, and she and her sister, Ariana, were staying with their grandparents that August when the Germans and the Russians divided Poland. Their mother was stranded on the Nazi side; her daughters were stuck across the border, under Soviet control. During the next few years, their father, Bernard, disappeared and, later, was eventually presumed killed in the war.

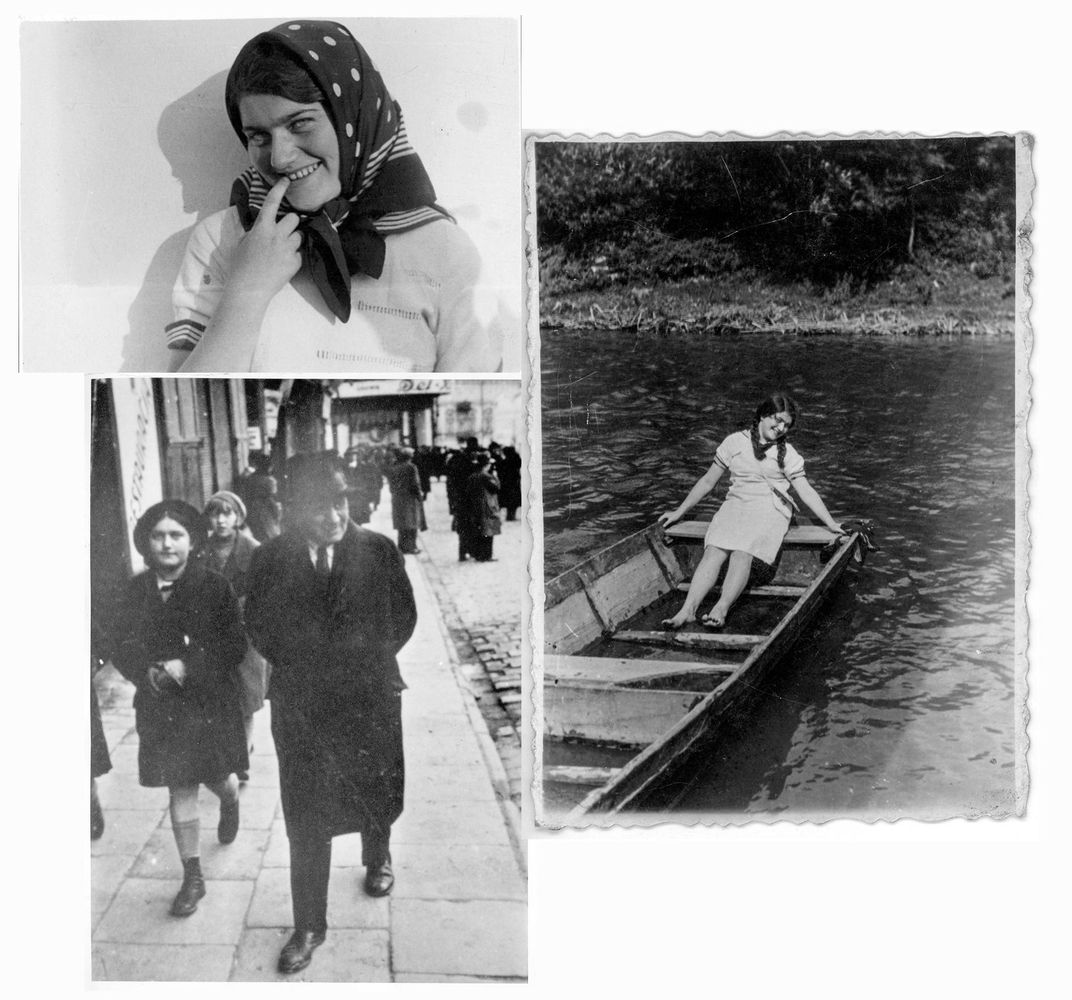

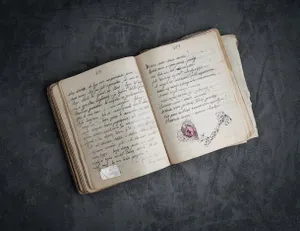

Over the course of more than 700 pages, between the ages of 15 and 18, Renia wrote funny stories about her friends, charming descriptions of the natural world, lonely appeals to her absent parents, passionate confidences about her boyfriend, and chilling observations of the machinery of nations engaged in cataclysmic violence. The notebook pages, blue-lined and torn at the edges, are as finely wrinkled as the face of the old woman the girl might have become. Her script is delicate, with loops at the feet of the capital letters and sweetly curving lines to cross the T’s.

Readers will naturally contrast Renia’s diary with Anne Frank’s. Renia was a little older and more sophisticated, writing frequently in poetry as well as in prose. She was also living out in the world instead of in seclusion. Reading such different firsthand accounts reminds us that each of the Holocaust’s millions of victims had a unique and dramatic experience. At a time when the Holocaust has receded so far into the past that even the youngest survivors are elderly, it’s especially powerful to discover a youthful voice like Renia’s, describing the events in real time.

A diary is an especially potent form in an age of digital information. It’s a “human-paced experience of how someone’s mind works and how their ideas unfold,” says Sherry Turkle, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who studies the role of technology in our lives. Throughout many continuous pages, she says, diary authors “pause, they hesitate, they backtrack, they don’t know what they think.” For the reader, she says, this prolonged engagement in another person’s thinking produces empathy. And empathy these days is in dangerously short supply.

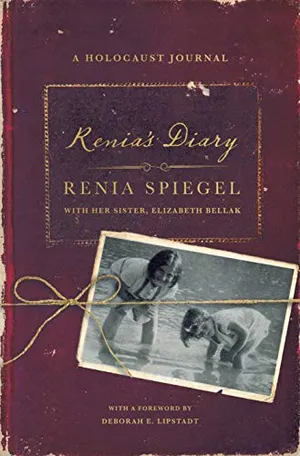

Renia's Diary: A Holocaust Journal

The long-hidden diary of a young Polish woman's life during the Holocaust, translated for the first time into English

Read our translation of Renia Speigel's diary here.

The history we learn in school proceeds with linear logic—each chain of events seems obvious and inexorable. Reading the diary of a person muddling through that history is jarringly different, more like the confusing experience of actually living it. In real time, people are slow to recognize events taking place around them, because they have other priorities; because these events happen invisibly; because changes are incremental and people keep on recalibrating. The shock of Renia’s diary is watching a teenage girl with the standard preoccupations—friends, family, schoolwork, boyfriend—come to an inescapable awareness of the violence that is engulfing her.

* * *

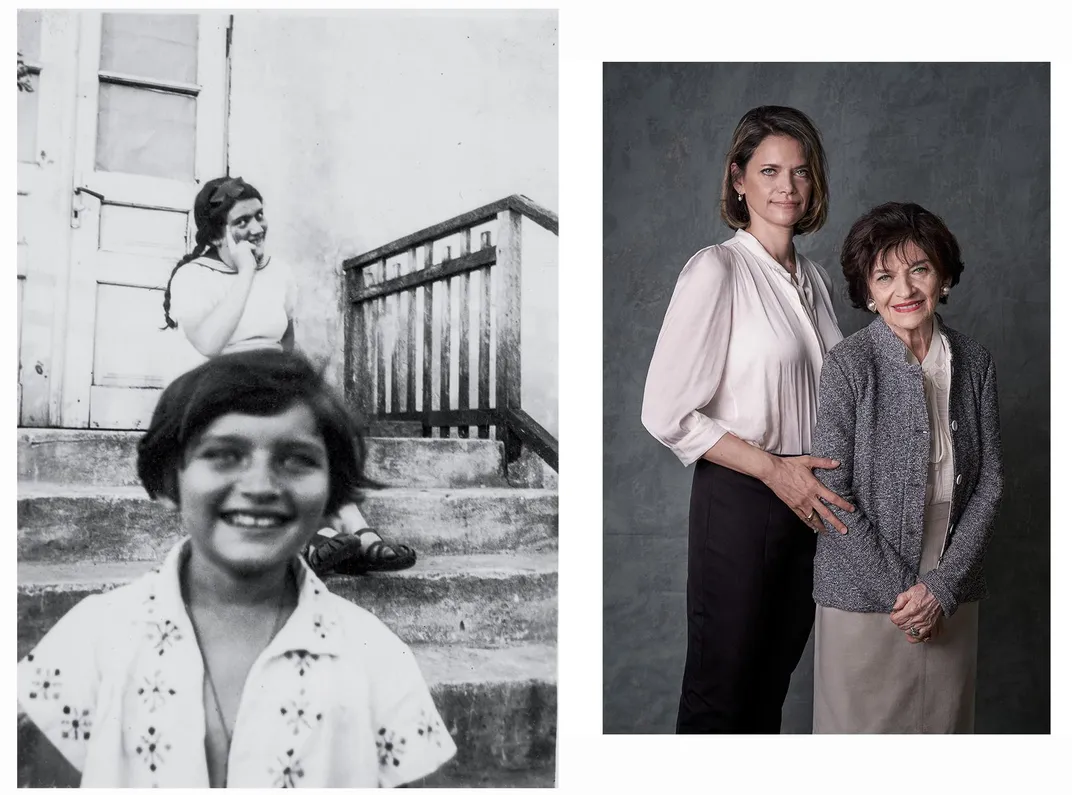

Renia began her diary feeling alone. Her gregarious, saucy 8-year-old sister Ariana was an aspiring film star who had moved to Warsaw with their mother so she could pursue her acting career. Renia had been sent to live with her grandmother, who owned a stationery store, and her grandfather, a construction contractor, in sleepy Przemysl, a small city in southern Poland about 150 miles east of Krakow. Ariana was visiting her at the end of that summer when war broke out. The sisters fled the bombardment of Przemysl on foot. When they returned, the town was under Soviet occupation.

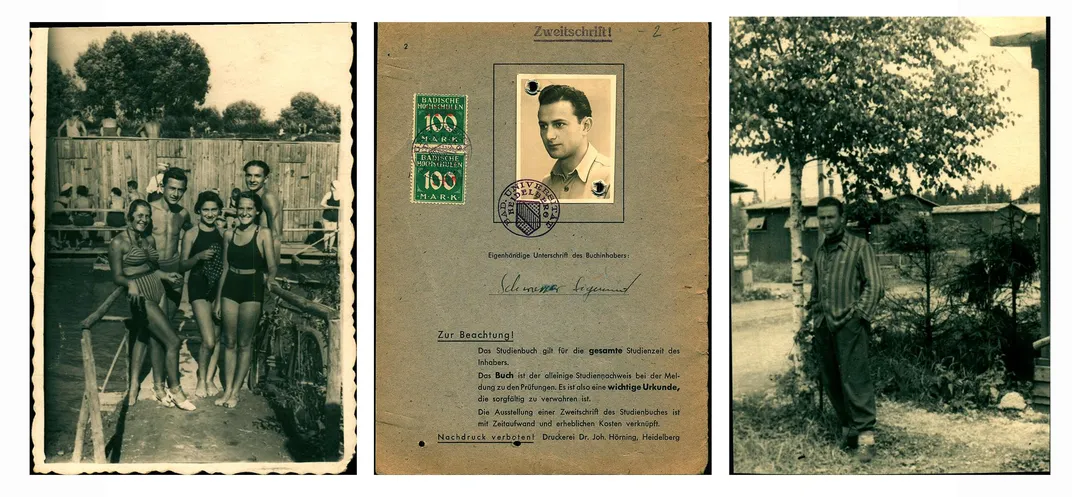

Two years later, just as the Germans were preparing to invade the Soviet Union, Renia had her first kiss with a green-eyed Jewish boy named Zygmunt Schwarzer, son of a doctor and a concert pianist. Renia, Zygmunt and Maciek Tuchman, a friend of Zygmunt’s (who now goes by the name Marcel), became a kind of trio. “We were tied to one another and living each other’s lives,” Tuchman recalled in a recent interview at his home in New York City.

Just two weeks before her 18th birthday in June 1942, Renia described understanding “ecstasy” for the first time with Zygmunt. But as her romance intensified, so did the war. “Wherever I look there is bloodshed,” she wrote. “There is killing, murder.” The Nazis forced Renia and her Jewish friends and relatives to wear white armbands with a blue Star of David. In July, they were ordered into a closed ghetto, behind barbed wire, under watch of guards, with more than 20,000 other Jews. “Today at 8 o’clock we have been shut away in the ghetto,” Renia writes. “I live here now; the world is separated from me, and I’m separated from the world.”

Zygmunt had begun working with the local resistance, and he managed a few days later to spirit Renia and Ariana out of the ghetto before an Aktion when the Nazis deported Jews to the death camps. Zygmunt installed Renia, along with his parents, in the attic of a tenement house where his uncle lived. The following day, Zygmunt took 12-year-old Ariana to the father of her Christian friend.

On July 30, German soldiers discovered Zygmunt’s parents and Renia hiding in the attic and executed them.

An anguished Zygmunt, who had held onto the diary during Renia’s brief time in hiding, wrote the last entry in his own jagged script: “Three shots! Three lives lost! All I can hear are shots, shots.” Unlike in most other journals of war children, Renia’s death was written onto the page.

* * *

Ariana escaped. Her friend’s father, a member of the resistance, traveled with Ariana to Warsaw, telling Gestapo officials inspecting the train with their dogs that she was his own daughter. Soon Ariana was back in her mother’s custody.

Her mother, Roza, was one of those astonishingly resourceful people who was marshaling every skill and connection to survive the war. She’d gotten fake papers with a Catholic name, Maria Leszczynska, and parlayed her German fluency into a job as assistant manager of Warsaw’s grandest hotel, Hotel Europejski, which had become a headquarters for Wehrmacht officers. She’d managed to see her children at least twice during the war, but those visits had been brief and clandestine. The woman now going by the name Maria was fearful of drawing attention to herself.

When Ariana was spirited out of the ghetto and back to Warsaw in 1942, Maria turned in desperation to a close friend with connections to the archbishop of Poland. Soon the girl was baptized with her own fake name, Elzbieta, and dispatched to a convent school. Taking catechism, praying the rosary, attending classes with the Ursuline sisters—never breathing a word about her true identity—the child actress played the most demanding role of her life.

By the end of the war, through a series of bold and fantastical moves—including a romance with a Wehrmacht officer—Maria found herself working for the Americans in Austria. Almost every Jew she knew was dead: Renia, her parents, her husband, her friends and neighbors. One of her sole surviving relatives was a brother who had settled in France and married a socialite. He invited Maria and Elzbieta to join him there—and even sent a car to fetch them. Instead, Maria procured visas for herself and her child to have a fresh start in the United States.

After burying so much of their identities, it was difficult to know which pieces to resurrect. Maria felt Catholicism had saved her life, and she clung to it. “They don’t like Jews too much here either,” their sponsor told them when they landed in New York. Ariana-cum-Elzbieta, now known as Elizabeth, enrolled in a Polish convent boarding school in Pennsylvania, where she told none of her many friends that she was born a Jew. Maria remarried, to an American, a man who was prone to making anti-Semitic comments, and she never told her new husband about her true identity, her daughter later recalled. When she died, she was buried in a Catholic cemetery in upstate New York.

Elizabeth grew up to become a schoolteacher. She met her husband-to-be, George Bellak, at a teachers’ union party, and she was drawn to him partly because he too was a Jew who had fled the Nazi takeover of Europe—in his case, Austria. But for a long time, Elizabeth didn’t tell George what they had in common. The fear of exposure was a part of her now. She baptized her two children and didn’t tell even them her secret. She began to forget some of the details herself.

* * *

But her past was not finished with her yet. In the 1950s, when Elizabeth and her mother were living in a studio apartment on Manhattan’s West 90th Street, Zygmunt Schwarzer tromped up the stairs, Elizabeth recalls. He had also survived the war and also resettled in New York City, and he was as handsome and charming as ever, calling Elizabeth by her childhood nickname—“Arianka!” He carried with him something precious: Renia’s diary. There it was, the pale blue-lined notebook, containing her sister’s words, her intelligence and sensitivity and her growing understanding of love and violence—delivered to this new life in America. Elizabeth could not bring herself to read it.

No one alive today seems to be able to explain the mystery of how, precisely, Renia’s diary had made its way from Poland to Schwarzer’s hands in New York—not Elizabeth, Tuchman or Schwarzer’s son, Mitchell. Perhaps Zygmunt Schwarzer had given it to a non-Jewish neighbor for safekeeping back in Poland; perhaps someone discovered it in a hiding spot and sent it to the International Red Cross for routing to the owner. After the war, photos, personal items and documents reached survivors in all sorts of circuitous ways.

What’s known is that by the time Schwarzer appeared with the diary, he’d survived Auschwitz Birkenau, Landsberg and other camps. In a testimony recorded in 1986, now on file at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Schwarzer said that Josef Mengele, the famous death camp doctor, personally examined him—and decided to let him live. Another time, he said, he was to be put to death for stealing clothes when a girlfriend showed up to pay a diamond for his release.

His camp was liberated in the spring of 1945. By the autumn of that year, his son says, he was studying medicine in Germany under former Nazi professors. He married a Jewish woman from Poland. After he finished school, they immigrated to America under the newly created Displaced Persons Act, the country’s first piece of refugee legislation. After a stint in the U.S. Army, he had a happy career as a pediatrician in Queens and on Long Island. His two children remember him as gregarious, brilliant, funny and kind, the sort of person who wanted to taste every food, see every sight and strike up conversation with every passerby, as if surviving the war had only amplified his zest for life.

But as he gained more distance from the past, his internal life grew darker. By the 1980s, he often wondered aloud why Mengele had allowed him to live. “What did he see in me?” he asked Mitchell. “Why did this man save my life?”

He had made a copy of the diary, and his basement office became a shrine to Renia. Her photograph hung on his wall. He would lay out photocopied pages of her diary on brown leather medical examination tables and spend hours poring over them. “He was apparently falling in love with this diary,” his son recalls. “He would tell me about Renia. She was this spiritual presence.”

Zygmunt Schwarzer’s wife, Jean Schwarzer, had little interest in her husband’s heartache—she reacted to the long-dead girl like a living rival. “My mother would say, ‘Ach, he’s with the diary downstairs,’” said Mitchell. “She wasn’t interested in all of what she would call his ‘meshugas,’ his crazy crap.”

But Tuchman, Schwarzer’s childhood friend, understood the need to reconnect with the past later in life. “We were clamoring for some attachment and the desire to see a common thread,” he explained recently. Survivors often sought out artifacts as a kind of anchor, he said, to feel that “we were not just floating in the atmosphere.”

Zygmunt’s son Mitchell took up the mantle of investigating that lost world. He traveled to his parents’ hometowns in Poland and the camps and hiding places where they survived the war, and spoke publicly about their stories. He became a professor of architectural history, publishing “Building After Auschwitz” and other articles about the Holocaust and architecture.

Zygmunt Schwarzer died from a stroke in 1992. Before his death, he had made a last contribution to Renia’s diary. On April 23, 1989, while visiting Elizabeth, he wrote one of two additional entries. “I’m with Renusia’s sister,” he wrote. “This blood link is all I have left. It’s been 41 years since I have lost Renusia.... Thanks to Renia I fell in love for the first time in my life, deeply and sincerely. And I was loved back by her in an extraordinary, unearthly, incredibly passionate way.”

* * *

After Maria died in 1969, Elizabeth retrieved her sister’s journal and stashed it away, eventually in a safe deposit box at the Chase bank downstairs from her airy apartment near Union Square in Manhattan. It was both her dearest possession and unopenable, like the closely guarded secret of her Jewishness. Her French uncle had always told her: “Forget the past.”

One day, when her youngest child, Alexandra, was about 12 years old, she said something casually derogatory toward Jews. Elizabeth decided it was time Alexandra and her brother, Andrew, knew the truth.

“I told them I was born Jewish,” Elizabeth said.

By the time Alexandra grew up, she wanted to know more about the diary. “I had to know what it said,” said Alexandra. In 2012, she scanned the pages and emailed them, 20 at a time, to a student in Poland for translation. When they came back, she was finally able to read her dead aunt’s words. “It was heart-wrenching,” she said.

In early 2014, Alexandra and Elizabeth went to the Polish consulate in New York to see a documentary about a Polish Jewish animator who had survived the Holocaust. Elizabeth asked the filmmaker, Tomasz Magierski, if he wanted to read her sister’s wartime diary.

Out of politeness, Magierski said yes. “Then I read this book—and I could not stop reading it,” he said. “I read it over three or four nights. It was so powerful.”

Magierski was born 15 years after the war’s end, in southern Poland, in a town, like most every other Polish town, that had been emptied of Jews. Poland had been the country where most of Europe’s Jews lived, and it was also the site of all the major Nazi death camps. At school, Magierski had learned about the Holocaust, but no one seemed to talk about the missing people, whether because of grief or culpability, official suppression or a reluctance to dredge up the miserable past. It seemed wrong to Magierski that not only the people were gone, but so were their stories.

“I fell in love with Renia,” he says, in his gentle voice, explaining why he decided to make a film about her. “There are hundreds of thousands of young people and children who disappeared and were killed and their stories will never be told.” This one felt like his responsibility: “I have to bring this thing to life.” He began visiting town archives, old cemeteries, newspaper records and the people of Przemysl, turning up information even Elizabeth had not known or remembered.

He also created a poetry competition in Renia’s name and wrote a play based on Renia’s diary. Actors from Przemysl performed it in Przemysl and Warsaw in 2016. The lead actress, 18-year-old Ola Bernatek, had never before heard stories of the Jews of her town. Now, she said, “I see her house every day when I go to school.”

For Renia’s family, though, the goal was publishing her journal. The book was published in Polish in 2016. It was not widely reviewed in Poland—where the topic of Jewish Holocaust experience is still a kind of taboo—but readers acknowledged its power and rarity. “She was clearly a talented writer,” Eva Hoffman, a London-based Polish Jewish writer and academic, said of Renia. “Like Anne Frank, she had a gift for transposing herself onto the page and for bringing great emotional intensity as well as wit to her writing.”

The night her diary was printed, Magierski stayed in the print shop the whole night, watching. “There was a moment where I became cold,” he said. “She’s going to exist. She’s back.”

* * *

Reading the diary made Elizabeth “sick,” she says, spitting out the word. An elegant 87-year-old-woman with startlingly pale blue eyes, sparkling green eyeshadow, carefully coiffed hair and a white lace blouse, she says she could only stand to take in a few pages of the diary at a time. Then she would feel her heart racing, her stomach churning, her body experiencing her sister’s—and her own—long-ago terror.

Yet she brought the diary along on the summer trip she has taken most every year for the past four decades to see her French relatives—people who called her not by her birth name but by her assumed Christian name, people with whom she never discussed the war, or their shared Jewishness. She showed the diary to them. They asked questions, and for the first time, she answered them.

Editor’s note, October 30, 2018: This story has been updated to correct a few small details about Renia Spiegel’s family’s life.

Hear O Israel, Save Us

Read our exclusive translation of Renia Spiegel's diary

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12/03/1203fe33-4596-4952-a5f2-f4f1e1646026/nov2018_n07_spiegeldiaryprologue.jpg)