Ortho-Novum Pill Pack • 1963

by Robin Marantz Henig

The sexual revolution didn’t start the moment the pill (pictured in above image) was approved for contraception, in 1960. The (usually male) doctors who prescribed it in those first years often had a policy of restricting its use to women who were married, and who already had children. No free-love proponents or feminist firebrands allowed.

Physicians at university health clinics had tough decisions to make in those early days, according to a 1965 New York Times Magazine article: Should they prescribe the pill to single girls? Perhaps, if the patient brought a note from her pastor certifying that she was about to be married. But for students with no matrimonial plans? “If we did,” one clinic staffer told the author of the Times article, Cornell professor Andrew Hacker, “word would get around the dorms like wildfire and we’d be writing out prescriptions several times a day.”

Hacker posed a similar question to his freshman class. “It is hardly necessary to say that a good majority of the boys thought this was a splendid idea,” he wrote. “But what surprised me was that most of the girls also agreed.”

Five years after that report, I became a Cornell freshman myself. By then the world had shifted. The Supreme Court had already ruled, in Griswold v. Connecticut, that married couples had the right to any contraception. Another case, Eisenstadt v. Baird, was wending its way to the Supreme Court, its litigants hoping the justices would expand that right to non-married women. (In 1972, they did.) Meanwhile, I had my first serious boyfriend, and we soon found ourselves in the waiting room of a Planned Parenthood clinic in downtown Ithaca. No one asked whether I was married. The physician examined me, wrote me a prescription—and soon I had my very own pill pack, complete with a flowered plastic sleeve that could slip discreetly into a purse. I stored my pills in the grungy bathroom my boyfriend shared with five roommates. The only time I even thought about whether my pill pack was “discreet” was when I went home for vacation and worried that my mother would figure out I was having sex.

The pill wasn’t a bed of roses, despite the flowers on that plastic sleeve. In those days it had very high levels of artificial progestin and estrogen, hormones that could lead to blood clots, embolisms and strokes, especially for women who smoked or who were over 35. And I suffered my share of side effects. It wasn’t until I went off the pill to get pregnant that I realized I wasn’t necessarily suffering from depression just because I got weepy for three weeks every month.

It was thanks to women’s health advocates that the risks and side effects of the early pill were finally recognized. Today’s formulations have about one-tenth the progestin and one-third the estrogen that their progenitors did. And each prescription comes with a clear statement of potential risks—the now-familiar patient package insert that accompanies all medication, a safeguard that was originally a response to consumer pressure regarding the pill.

By the time I got married, in 1973—to that first serious boyfriend—36 percent of American women were on the pill. Hacker’s 1965 article proved to be prescient: “Just as we have adjusted our lives to the television set and the automobile, so—in 20 years’ time—we shall take the pill for granted, and wonder how we ever lived without it.”

Shirley Chisholm’s campaign buttons • 1972

Grace Hopper’s nanosecond wire • 1985

Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog” record • 1953

Celia Cruz’s shoes • 1997

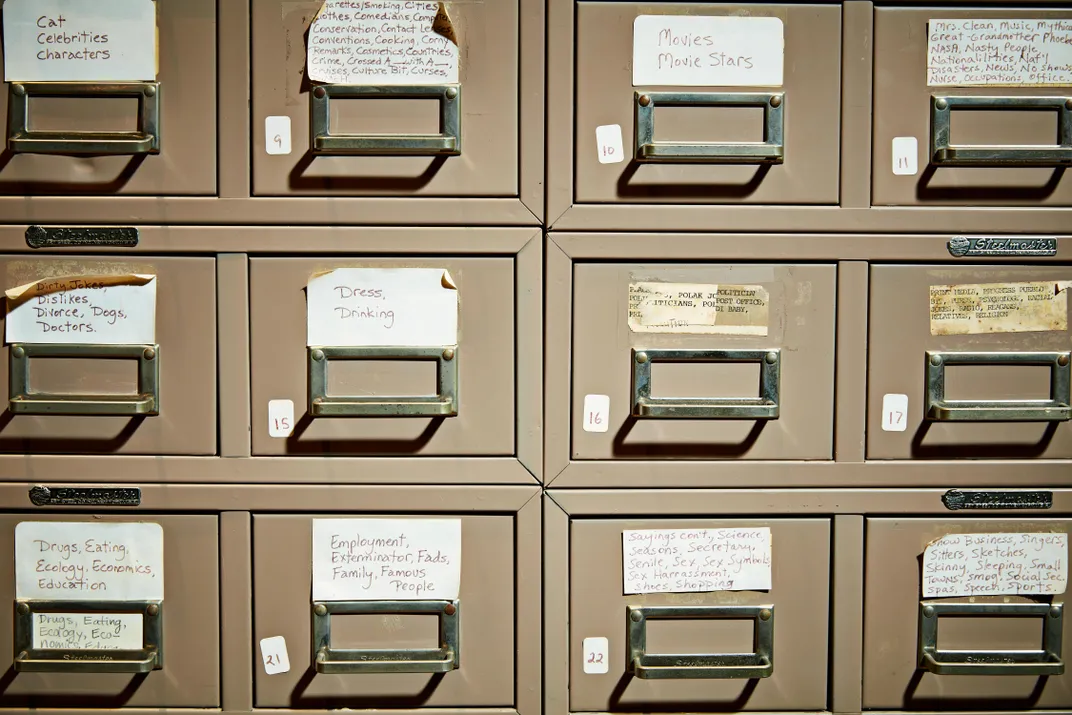

Phyllis Diller’s gag file • 1960s

by Margaret Cho

I met Phyllis Diller in the early 1990s when we were filming a Bob Hope special together. She was in her 70s then and didn’t seem old when the cameras were off. But as soon as we started rolling, she really exaggerated her age. Bob himself was seriously old at that point—when you were talking to him, he would forget what he was saying mid-sentence. You could be standing right in front of him and he’d barely even know you were there. He was basically a ghost of who he’d been. It was almost as if Phyllis was trying to play older to make him feel better. But she was always very on top of it, always completely there.

No one was doing what Phyllis did before she came along. When you think of someone like Lucille Ball—she played the game of the housewife. She was bubbly and goofy, and she really did obey Ricky, even if she rebelled a little bit. She never tried to degrade him or outshine him.

Phyllis pushed back against the idea of women as comforting mother figures. She had five children by the time she made her first television appearance, on “You Bet Your Life” in 1958. Groucho Marx asked her, “Phyllis, what do you do to break up the monotony of housekeeping and taking care of five small gorillas?”

“Well,” she said, “I’m really not a housewife anymore. I beat the rap.” That was an incredibly shocking thing for her to say in 1958!

There was so much edge to her comedy. She wore those over-the-top outfits and crazy hair, ridiculing the image of the perfectly groomed housewife. She made brutal jokes about her husband, “Fang.” She said, “This idiot that I portray on stage has to have a husband, and he’s got to be even more idiotic than I.” Her whole persona was alarmingly crass. She showed that women could have a lot more agency and strength than people believed, that they could act out of rage as opposed to just being goofy. She made herself someone to be feared, and she really enjoyed wielding that battle-ax.

And yet she was embraced by the television culture, which was usually incredibly restrictive. When you think about Steve Allen or Sid Caesar, they were part of the ultimate boys’ club, but they let her sit at the table with them. She figured out early on how to disarm her audiences. As a woman in comedy, you can’t be too pretty. Even when I started out in the ’90s, we were all trying to be tomboys like Janeane Garofalo. Now that I’m 50, it’s a lot easier. I think a younger comedian like Amy Schumer has a hard time being taken seriously because she’s pretty and young. There’s a lot of pressure to downplay your power.

In Phyllis’ case, she didn’t downplay her power. She exaggerated it with her crazy clothes and her eccentric mannerisms. That worked just as well.

When it comes to being subversive, female comedians have an advantage in a way because it’s such a radical idea for a woman to have a voice at all. That’s still true. Phyllis was one of the first comedians who figured out how to use her voice to question authority and challenge the way things were. She knew that when you’re entertaining people, you get across ideas in a way they’re not expecting. They think you’re giving them a magnificent gift, and then they get a surprise. They don’t realize it’s a Trojan horse, filled with artillery. She got so much feminism into a character that seemed like a hilarious clown.

Being with Phyllis in person was always a surreal experience. She would yell things like, “Never, ever, ever touch me!” And I never did, so that was good! But I was always enthralled by her: I have a sculpture in my house that’s made partly out of empty pill bottles from Phyllis Diller. None of us women in comedy could be doing what we’re doing if it weren’t for her. And I don’t think anyone today could even begin to approach what she did starting in the 1950s. She was so electric and revolutionary.

Nannie Helen Burroughs’ cash register • 1904

Helen Keller's watch • 1892

Chris Evert's tennis racket • c. 1978

Pink protest hat, Women’s March • 2017

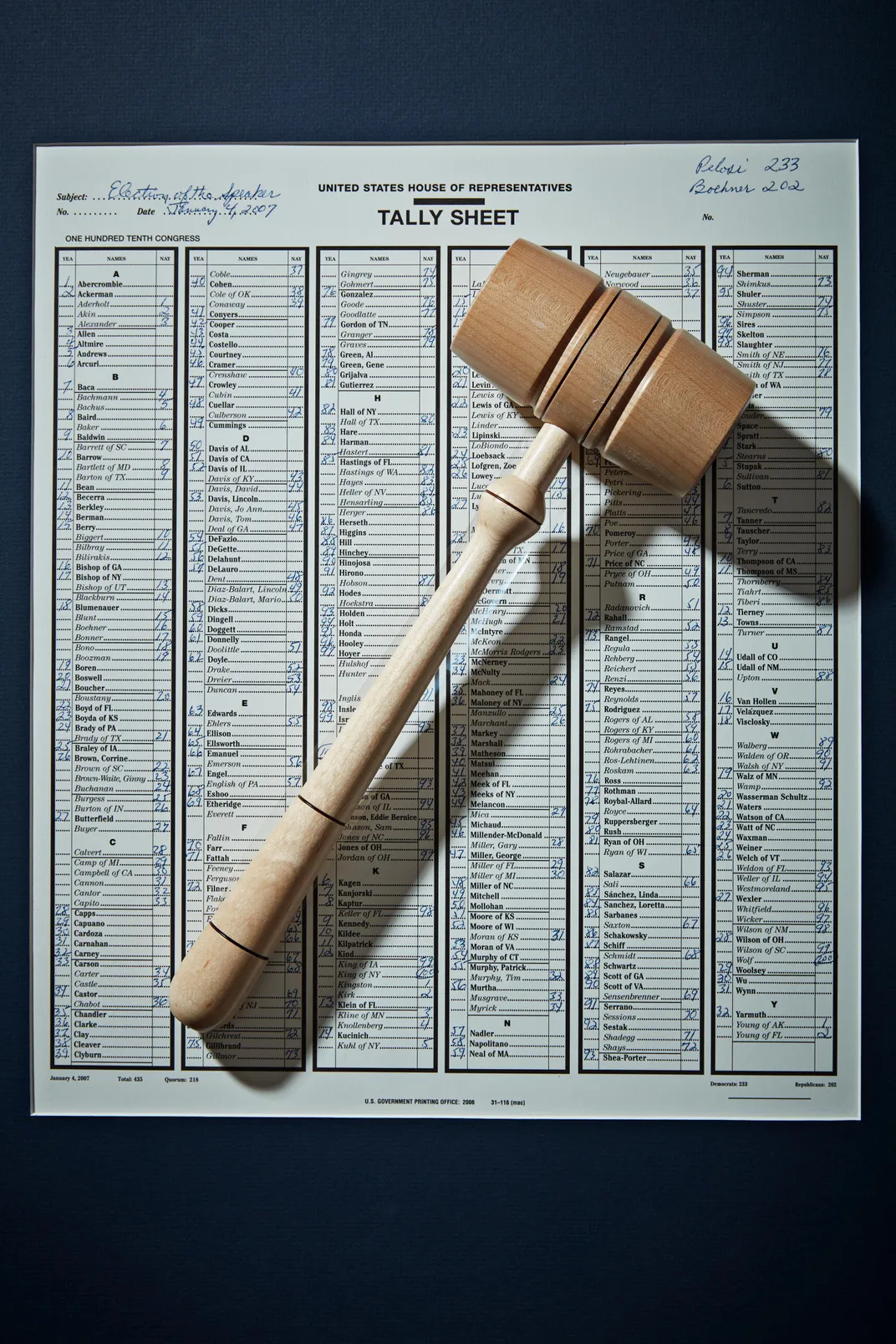

Nancy Pelosi’s gavel • 2007

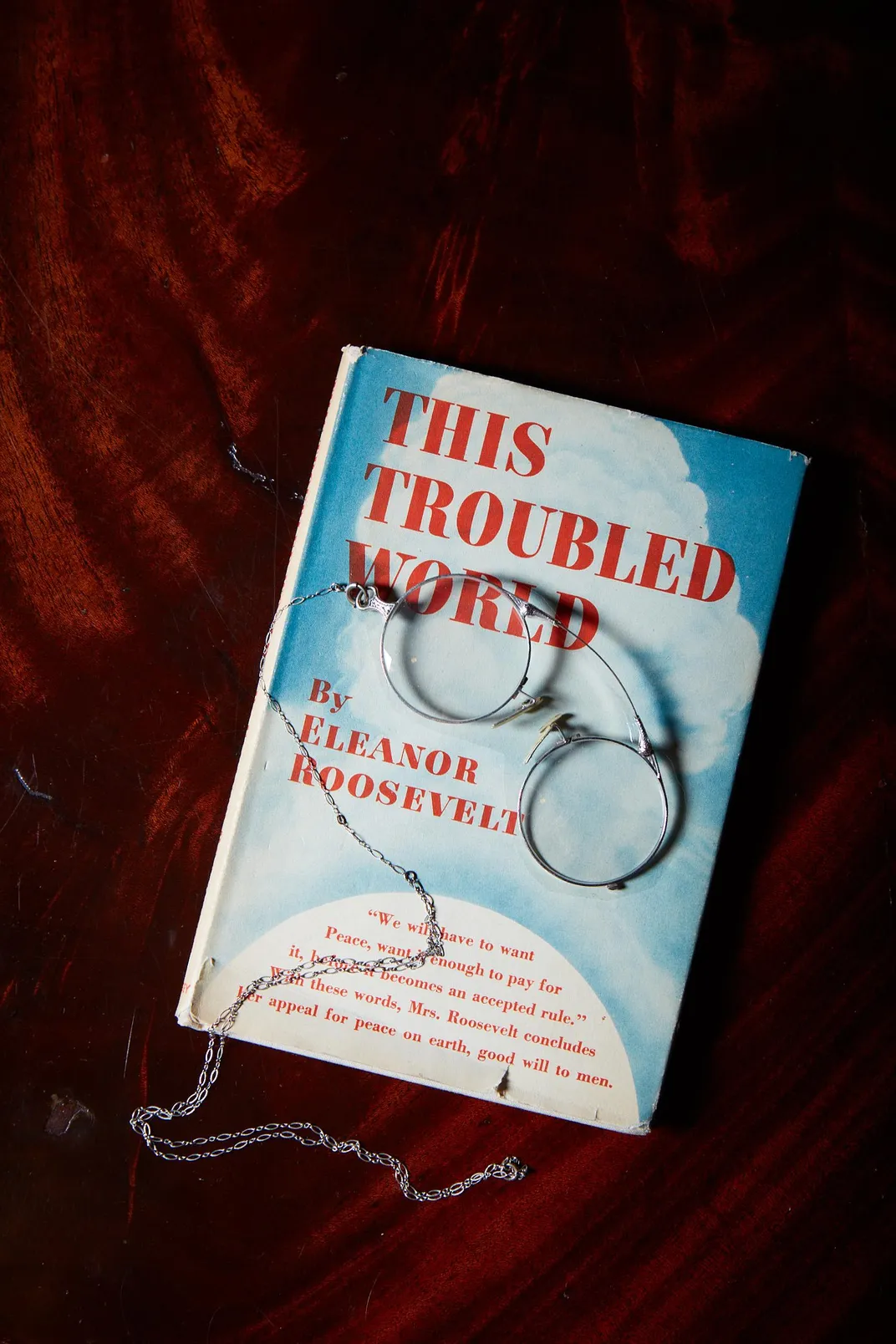

Eleanor Roosevelt's reading glasses • c. 1933

Gertrude Ederle’s goggles • 1926

by Sally Jenkins

At 7:09 a.m. on August 6, 1926, Gertrude Ederle set off across the English Channel wearing a pair of glass aviator goggles sealed with wax. “England or drown is my motto,” she said before wading into the sea in Cape Gris-Nez, France. Tossed up and down by six-foot waves, she churned through the water as if she had no choice but to keep moving or die.

Ederle was a 20-year-old butcher’s daughter from New York who looked forward to owning a red roadster, a gift her father had promised her if she swam across the channel successfully. In 1926 only five men had accomplished that feat. No woman had done so. “In her day it was the mythic swim of the world,” says the renowned open-water swimmer Diana Nyad.

Ederle was a well-muscled Olympic medalist and world record-setter. It was reported that her inhale was so deep that she had a chest expansion of eight inches. (In contrast, slugger Babe Ruth and prizefighter Jack Dempsey each had a chest expansion of less than four inches.) She had swagger aplenty, too. “Bring on your old channel,” she’d said before her first crossing attempt, in 1925. That time, one of her coaches had pulled her from the channel before she reached England, either because he feared she would faint or because he couldn’t bear to see a teenage girl do what he couldn’t. As Ederle said afterward, “I never fainted in my life.”

Now, a year later, the 61-degree water was once again throwing her from peak to trough as the North Sea collided with the surging Atlantic in the Strait of Dover. Ederle plied the chop with her American crawl—the powerful new overhand that had helped her win a gold and two bronze medals at the 1924 Olympics in Paris.

She followed a Z-shaped route, designed to cut across currents and catch favorable tides. Her suit was a thin silk affair; she’d cut away its skirt to streamline it. Her skin was covered with nothing more than grease to ward off hypothermia. An assistant in an escort boat fed her chicken broth out of a bottle lowered on a fishing pole. The crew played “Yes, We Have No Bananas” on a Victrola to pace her.

Through her crude goggles, Ederle could glimpse a variety of hazards: Portuguese men-of-war, sunken wrecks and sharks, whose carcasses were regularly hung on the wall at the post office in Boulogne. The wax with which she’d sealed the goggles came from her dinner candles. “A channel swimmer today puts on a weightless pair of goggles that sit with perfect suction,” Nyad says. “She’s wearing motorcycle goggles, like the ones Snoopy wore when he was flying his biplane.”

About halfway across the channel, the weather turned stormy, with 25-mile-per-hour winds and swells that made the boat passengers lean over the gunwales and throw up. “Gertie will have to come out. It’s not humanly possible to go on in a sea like this,” her coach, Bill Burgess, said. Someone cried, “Come out! Come out!” Ederle bobbed back up and shouted, “What for?”

At 9:40 p.m. she staggered onto British shores to a cacophony of boat horns. Several women dashed into the water, getting their hems wet, to kiss her. Her father wrapped her in a robe. “Pop, do I get that red roadster?” she asked. Decades later she admitted to Nyad, “I was frozen to the bone. I’m not sure I could have stood another hour.”

With her time of 14 hours and 31 minutes, Ederle (who died in 2003) not only became the first woman to cross the 21-mile channel but obliterated the men’s record by two hours. The New York Herald Tribune sports editor W. O. McGeehan wrote, “Let the men athletes be good sportsmen and admit that the test of the channel swim is the sternest of all tests of human endurance and strength. Gertrude Ederle has made the achievements of the five men swimmers look puny.”

It was, and remains, a monumental accomplishment. As Ederle’s biographer Glenn Stout noted in 2009, “Far fewer human beings have swum the English Channel than have climbed Mount Everest.” Her record was not broken until 1950—by Florence Chadwick, another American woman, who swam the channel in 13 hours and 20 minutes. And yet, as Nyad says, “We still after all these years look at women, like, ‘Gosh maybe it’ll hurt ’em.’”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/3b/463b4487-9ada-4368-8419-2aa593310fee/womens-objects-lead-image-for-web_resized.jpg)