Odd McIntyre: The Man Who Taught America About New York

For millions of people, their only knowledge about New York City was O.O. McIntyre’s daily column about life in the Big Apple

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/McIntyre-New-York-City-Times-Square-1927-631.jpg)

On a steamy July day 100 years ago, a 27-year-old newspaperman stepped off the train from Cincinnati at Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan. He wore a checkered suit, carried a bamboo cane and would have put on his loudest red necktie had his wife not talked him out of it. Years later he’d cringe at his youthful fashion sense but remember his first glimpse of Manhattan with awe. He called it “life’s most thrilling moment.”

So began one of the great romances of the 20th century. “I came to New York with no special qualifications, no brilliant achievements and certainly nothing to recommend me to metropolitan editors,” he said. “Yet New York accepted me, just as it has thousands of others who came from the prairie cottage and the village street, so generously and wholeheartedly that I love it devotedly.”

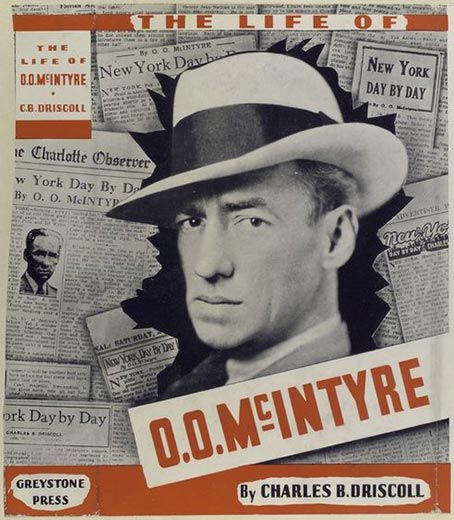

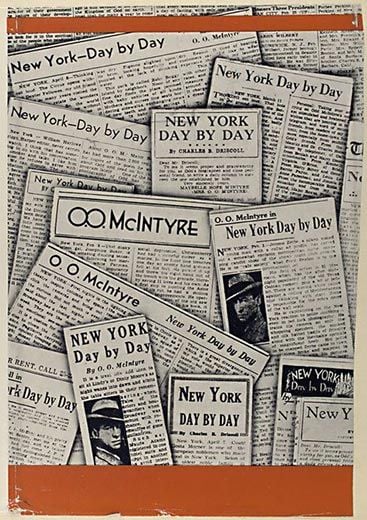

By the early 1920s, O. O. (for Oscar Odd) McIntyre was perhaps the most famous New Yorker alive—at least to people who didn’t reside there. His daily column about the city, “New York Day by Day,” reportedly ran in more than 500 newspapers throughout the United States. He also wrote a popular monthly column for Cosmopolitan, then one of the country’s largest general-interest magazines. His annual output totaled some 300,000 words, the bulk of them about New York. In return for all that time at the typewriter, he was reputed to be the most widely read and highly paid writer in the world, earning an estimated $200,000 a year.

McIntyre’s most devoted audience was small-town America, where readers saw him as a local boy turned foreign correspondent, reporting from an exotic, faraway place. He referred to his daily column as “the letter,” and its tone often resembled a note to the folks back home. “[T]he metropolis has never lost its thrill for me,” he once wrote. “Things the ordinary New Yorker accepts casually are my dish—the telescope man on the curb, the Bowery lodging houses and drifters, chorus girls, gunmen,” as well as “speakeasies on side streets, fake jewelry auction sales, cafeterias, chop houses, antique shops, $5 hair bobbing parlors—in short all the things we didn’t have in our town.”

In any given column he might pay tribute to some neighborhood of the Big Town, reminisce about his youth in Gallipolis, Ohio, and sprinkle in personal glimpses of the famous men and women he seemed to bump into everywhere he went:

“Jack Dempsey is one of the most graceful dancers in town….”

“Amelia Earhart’s bob is now like Katharine Hepburn’s….”

“Ernest Hemingway waxes furious when it is spelled with two m’s….”

“Babe Ruth doesn’t enjoy dinner without an ice cream finale….”

“Charlie Chaplin cannot talk business to any man behind a desk. His youth was filled with rebuffs over a desktop….”

“Joseph P. Kennedy takes one of his nine children to a matinee every Saturday….”

New York, he told his readers, was “a sort of parade ground for celebrities.” Unlike later gossip columnists, McIntyre took pride in the notion that he had “never intentionally written a line I thought would wound the feelings of another.” Indeed, you can read hundreds of “New York Day By Day” installments and never come across anything more critical than, “Bob Ripley is putting on weight.”

At his peak, McIntyre was receiving 3,000 fan letters a week, including some addressed simply to “O. O., New York.” He was parodied by Ring Lardner and celebrated in a suite by Music Man composer Meredith Wilson. When the longtime New Yorker editor William Shawn published his sole piece in the magazine (a 1936 sketch about a meteor wiping out everybody in all five New York boroughs), he singled out McIntyre as the only person the rest of the country even noticed was missing.

What few of McIntyre’s out-of-town readers might have realized was that his New York often bore about as much resemblance to the real city as a Busby Berkeley musical. “Accuracy was his enemy and glamor was his god,” the New York Times observed in its obituary of him. “His map of New York came from his own imagination, with Hoboken next to Harlem if it suited his fancy, as it often did.”

Even fewer readers could have known that for much of his life, McIntyre suffered from a set of phobias that were remarkable in both number and variety. Those included a fear of being slapped on the back or having someone pick lint off his clothing. He was terrified that he might drop dead in the street. He disliked crowds and often preferred not to leave his Park Avenue apartment at all, except for nightly rides around the city, hunched in the back of his chauffeured blue Rolls-Royce. Further complicating his work as a reporter, he was deathly afraid of the telephone.

In many ways the name “Odd,” which he inherited from an uncle, could hardly have been more fitting. Among other things, he wrote mostly in red ink, owned 30 pairs of pajamas for wearing during the day and another 30 for the night, and loved to sprinkle himself with perfume. One interviewer counted 92 bottles on his bureau. Rival gossip columnist Walter Winchell wasn’t alone in calling him “the Very Odd McIntyre.”

McIntyre and his wife, Maybelle, were childless but owned a succession of dogs, including a Boston terrier named Junior and another named Billy, whose exploits were chronicled in endless detail. “I have often thought my friend O. O. McIntyre gave more space in his column to his little dog than I do to the U. S. Senate,” Will Rogers once wrote. “But it just shows Odd knows human nature better than I do. He knows that everybody at heart loves a dog, while I have to try and make converts to the Senate.” Billy was the subject of such classic McIntyre fare as “To Billy in Dog Heaven,” which supposedly elicited more mail than any other of his columns.

McIntyre died on February 14, 1938, days shy of his 54th birthday, apparently of a heart attack. His biographer and longtime editor, Charles B. Driscoll, speculated that he could have lived a lot longer had he not been afraid of doctors.

His death and the return of his body to Ohio were national news. Before his burial on a hillside overlooking the Ohio River, his remains lay in state at a Gallipolis mansion he and his wife had bought, renovated and furnished for their eventual return. McIntyre had written about the home but never set foot in it during the five years he owned it.

Today, a century after his arrival in New York, Odd McIntyre may be best known as the name of a cocktail—a mix of lemon juice, triple sec, brandy and Lillet. The O. O. McIntyre Park District in Gallia County, Ohio, bears his name, as does a journalism fellowship at the University Missouri. His name also concludes the official poem of the state of Oklahoma, which honors his friend Will Rogers: “Well, so long folks, it’s time to retire/I got to keep a date with Odd McIntyre.” But that’s about it.

McIntyre’s return to obscurity would probably not surprise him. “I am not writing for posterity nor do I believe anything I write will live for more than a week or so after publication,” he once insisted. “I have found satisfaction in entertaining people a little every day.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/greg2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/greg2.png)